What is resolution in photography

The world of images is digital. It is digital in the sense that there is no image capture system that is a continuum, that is not an aggregate of individual sensors. This happens with our eyes, with photographic film and also with digital sensors.

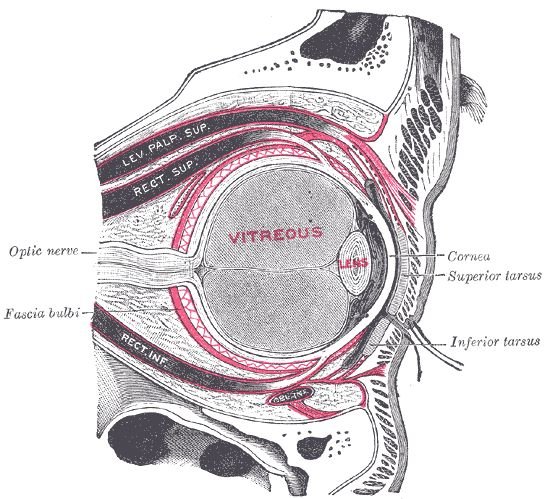

Our eyes are digital

To start with our eyes, the image produced by the lens on the retina, which is our screen, is projected onto a surface full of individual cells each sensitive to a certain part of the spectrum. But they are individual cells and vary in size depending on their position on the retina, but in the most sensitive and sharpest part, these cells are approximately 1.5 to 2.0 microns, or thousandths of a millimeter.

Above is a graphic representation illustrating the distribution of light-sensitive cells in the human eye. They are more concentrated in the center, in the fovea, and more dispersed in the periphery. They are also sensitive to different wavelengths: red, green and blue. If this is too strange for you, read about Light and Colors, what is physical and what is human. But for this article the important thing to know is that they are individual cells and not a uniform medium.

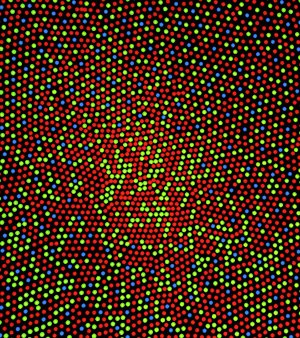

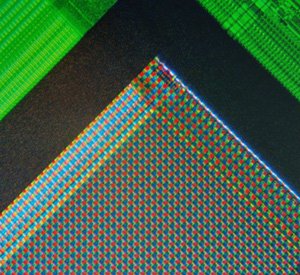

The digital camera is digital

Much like the human eye, the digital sensor has the same characteristics as individual sensors. Each type serves a specific wavelength and again: red, green and blue. The difference is that in this case they are arranged in a regular grid and are all the same size. Roughly speaking, in the current state of technology at the beginning of the 21st century, the order of magnitude is microns, just like in the human eye.

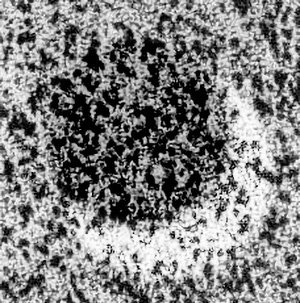

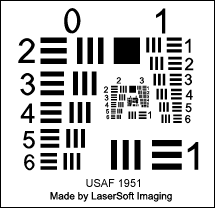

Analog film is digital

In this case, the developed film shown above is not really a sensor, but a record of something that was once sensitive to light. What we see are silver crystals forming, individual pebbles that vary in size, but as in the case of the human eye or the digital sensor, we again have a situation where the image is formed by a collection of things and not by a continuum, the variations in light and dark are obtained by the concentration and sizes of these crystals. The average size of these crystals is around 2 to 3 microns for a fine-grained film.

Object size and distance x image size

The fact that all image recording is conditioned to individual micro sensors, whether in our eyes, the digital camera or analog film, means that anything whose image is even smaller than these sensors cannot be seen in any detail.

That’s exactly what happens when we’re on the road at night and a car with two headlights makes us believe it’s a motorcycle with just one headlight. What’s happening at that moment is that the lights coming from each headlight separately end up being projected onto our retina, so close together that they fall on the same cell. Our brain understands this as a single point.

If, instead of being very far away, the object is in fact very small, even at a short distance, the effect can be the same. This is the case, for example, when we look at a computer screen and can’t see a single pixel in isolation from its neighbor. Although the distance from our eyes to the screen is short, the distance from a pixel to its neighbor is proportionally much shorter, and this causes them to be blended together like the headlights of a very distant car.

1 minute arc: the magic angle

It’s not hard to imagine that the relationship in question can be summed up as an angle. For humans, the angle separating two observed points needs to be on average of the order of 1/60th of 1 degree for the points to be perceived as separate. The circle is 360º. Take 1º (one degree) and if the angle of vision of the two physically distinct points is less than this degree divided by 60, then they will not be seen as distinct by our eyes. They will both fall into the same light-sensitive cell. This is the common magnitude in the example of the car on the road at night and the pixels on the monitor.

As degrees and hours are not decimal and are divided precisely by 60, this angle has a special name which is ” arcminute “. So we say that if the angle of vision in relation to our pupil is less than one arcminute, everything within that angle will be seen as one thing.

Resolution

In order to be able to compare different image production and recording systems in terms of the extent to which they can distinguish very close things, the concept of resolution was created.

The idea is very simple: imagine a sheet of paper with white stripes alternating with black stripes. The image of this sheet, produced by any lens, will result in a certain number of stripes per centimeter, millimeter or inch: the number of stripes per unit length defines the resolution. Mind you, it’s the stripes on the image that count, not on the sheet.

If the distance between the stripes in the image is small enough, the system that should see the stripes separately will only see a continuum because its individual sensors are too big for such a small image.

The resolution of a system is a number that tells you the maximum number of stripes or lines per unit length that the system, which will view or record the image, can still distinguish the lines from each other.

Resolution units

We need to be careful when talking about resolution not to confuse two widely used but different quantities. One is the number of points and the other is the line pair. They end up on the same thing but with a factor of 2 between them. Each line pair uses two points: one for black and one for white, or any other alternation in the image. So when a system has a resolution of 30 lp/mm or line pairs per millimeter, we’re actually talking about 60 dots, or 60 pixels, per millimeter.

Not every lack of sharpness is a problem of resolution

Although the resolution of the medium (film, sensor, retina) is a finite and inescapable characteristic for the sharpness of any imaging system, it’s worth remembering that there are other variables that interfere with image quality. Lenses, even the most sophisticated ones, are always subject to a certain amount of aberration that blurs and distorts images. Depth of field is another important variable that affects the focus zone and therefore sharpness outside it.

Still on the subject of lenses, they also have a resolving power that is not infinite. The image would not be perfect, with microscopic details, even in a hypothetical infinite resolution film. The image itself already has a finite resolution determined by a calculated quantity known as the circle of confusion and also by the position of the area being examined, whether it is close to or far from the lens axis, inside or outside the focus zone.

Camera and lens manufacturers need to find a reasonable match between the resolution of the support and the resolution of the lens. There’s no point in putting wonderful optics on a camera with huge pixels, or film with huge grains, and therefore little resolution. The opposite is also not advisable: a super-fine sensor or film with a low-resolution lens, incapable of providing detail, will only highlight the limitations of mediocre optics.

The final resolution on the film or sensor, in the case of photography, is the result of combining the resolution of the film or sensor itself under ideal conditions, depending on its physical characteristics, like the size of the silver grains or the geometry of the pixel grid, with the resolution of the lens, also under ideal conditions, in relation to the circles of confusion it produces.

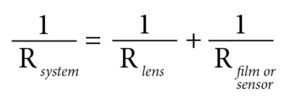

For those who are familiar with interpreting mathematical formulas, the relationship is as follows:

R is the resolution. It’s easy to see that if the resolution of the lens is the same as that of the film/sensor, the resolution of the two together is only half as high.

If, hypothetically, the resolution of the lens were infinite, its term would go to zero and the resolution of the system would be equal to the resolution of the film. And vice versa, if the resolution of the film were infinite.

The case of Leica

On the question of lens resolution vs. film, in the history of Leica’s development, we have an interesting case of the decisions involved. The camera was going to use 35mm film. But at that time, the early 1920s, the resolution of these films was very low.

To make matters worse, you have to remember that a 35mm negative still needs to be enlarged to produce a reasonable exhibition copy. At the time, 13 x 18 cm was acceptable and 18 x 24 cm a good size even for professional photography. To guarantee detail in the image, most photography was done with large negatives and often contact printed. With this condition, even very pronounced grain didn’t compromise the result so much. But 35 mm film with very large grains and low resolution, if it was further enlarged, would give photos with an apparent lack of definition.

The interesting thing about Leica’s story is that they decided to release a lens far ahead of the resolution of the film available at the time, hoping that in the future film would improve.

In an account by Ulf Richter in the book Eyes Wide Open, 100 Years of Leica Photography, he says that at the meeting discussing the launch, Max Berek, the lens designer, talks about his legendary Elmar 50mm f/3.5 lens in the following terms:

“We need a million clear pixels on the 800 mm² of the negative [24×36=864], so that a focused image is projected when it is enlarged to a size suitable for viewing. The lens [the Elmar he had developed] can do this, its resolution is well above that of film. I’m sure the films will be improved soon”.

First of all, it may seem strange that he should talk about “pixels” in 1925, in fact this was a liberty of the English translator. But the term Max Berek used was probably Bildpunkte, in German, which literally means: image point, which is exactly the same thing.

He meant that the final image needed to be able to distinguish something like 1000 x 1000 (one million) points in the image that unfortunately, at that time, would not be resolved by film in combination with an average lens of the time.

1000 dots in the length of 36 mm, which is the largest side of the 24 x 36 mm film frame, means Bildpunkte (pixels) in the ratio of 28 dots per millimeter (1000 ÷ 36) that the cinema film would need to be able to register individually. This would give 14 lp/mm (line pairs per mm) because the ratio between dots and lines is 1:2, as we saw above.

The Elmar was designed to give a resolution of 60 to 80 lp/mm, well above the 30 lp/mm that the cinema film available at the time could give. It seemed like a waste of a lens because the two together (formula above using 70 lp/mm) gave only 21 lp/mm. The lens pushed the resolution up, but relatively little, as the film held it at a still low level.

This means that the first Leica users couldn’t appreciate all the qualities of their optics, all the fine details that the Elmar could render, because these were lost by a film with very coarse grain and unable to distinguish so many details.

Panatomic X, redemption

In 1933, eight years after the launch of the Leica I model A, Kodak Panatomic X film was launched. It was a film initially designed for military use because of its very fine emulsion and tiny grain size, making it ideal for aerial reconnaissance photography, for example. But it was soon “discovered” by the then more than 100,000 Leica owners. It proved to be the perfect film for a miniature format. When the following year Kodak launched 35mm film in pre-loaded cartridges, which received the code 135, Panatomic X, ISO 32 was already part of the portfolio.

It was as if Leica users still didn’t know what the little camera could deliver. Unveiling the first roll of Panatomic X must have been a huge surprise. The enlargements showed a level of detail totally unknown for 35mm film photography until then.

The new Kodak film, soon followed by Agfa, was capable of offering a resolution of 80 lp/mm and the combined resolution, optical + film, practically doubled the resolution overnight.

| year / movie | lens resolution (lp/mm) | film resolution (lp/mm) | combination resolution |

| 1925- movie film | 70 | 30 | 21 |

| 1933- Panatomic X | 70 | 80 | 37 |

Leica x Human Eye

The central part of our retina, the fovea centralis, measures approximately 1.5 mm in diameter and contains around 200,000 cones (light-sensitive cells). If we include the parafovea, which is the surrounding area, the total cone count reaches 6 or 7 million for the entire retina. The goal with Elmar for the 24 x 36 mm format was, as we have seen, 1 million pixels. By proportioning the areas, the resolution sought was similar to that of the retina.

Max Berek wanted the Leica to see as well as the human eye. By aiming for 1 million dots, he ensured that if you held a Leica print at a normal viewing distance, the ‘grain’ of the camera would be smaller than the ‘grain’ of your eye (1 minute of arc). At that point, photography ceases to be a collection of dots and becomes, for our brains, reality.