Elizabeth Eastlake, Photography

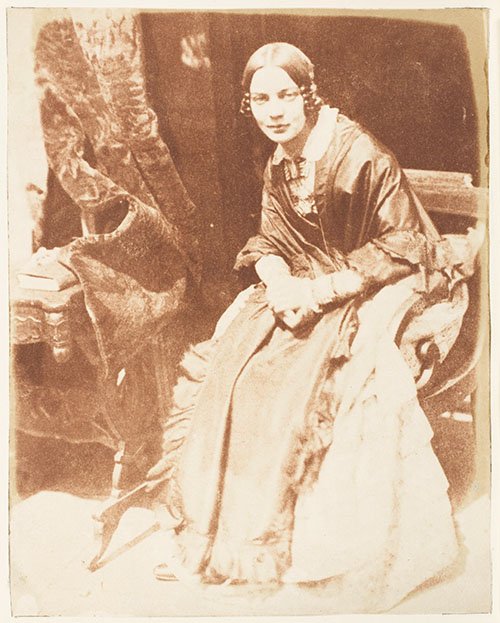

Lady Elizabeth Eastlake – Hill and Adamson – 1843-47

In 1857, the Englishwoman Elizabeth Eastlake, then 48 years old, published an extremely influential text with the simple but very ambitious title: Photography. As soon as photography was announced to the world, a passionate debate began about whether or not it should be considered an art form. More than a yes or no question, the interesting thing about studying this text is to see how it addresses the issue, how it constructs its arguments.

In the first part, she gives a very detailed summary of the main milestones in the achievement of the techniques needed for photography. This alone is of great historical value if we consider that she was a contemporary of many of these events and that she had a solid education and access to key figures in both science and the arts. She was, so to speak, a very well-informed witness to the events she recounts.

In this first part, Eastlake relativizes, not to say destroys, photography’s supposed position as the “mirror of nature”. For example, at one point he talks about the inability to reproduce the fine gradations of light at the extremes of the tonal range:“Their strong shadows swallow up all the timid lights within them, just as their flaming lights obliterate all the intrusive half-tones that pass through them; and thus strong contrasts are produced, which, far from being faithful to Nature, seem to avoid one of her most beautiful providences.“

Regarding its relationship or the possibility of it being an art form, your denial is very well founded. But we have to bear in mind that the 19th century was a kind of climax to a vision that, beginning in the Italian Renaissance, had placed nature as the source of all the arts, to the point where Leonardo da Vinci wrote that nature was his only teacher.

But here comes a second “but”: but we shouldn’t fool ourselves into thinking that to have nature as a teacher it’s enough to do the same as nature, because it’s precisely the meaning of this “doing the same” that was in dispute. There was a lot of disagreement on this point. Disagreement that began in painting and continued unresolved in photography. That the artist should be faithful to nature was something of a consensus, but what did this mean in practice? Would being faithful mean reproducing the retinal image? Would it finally be the mirror? Or would it mean giving a vision of the whole, of an essence, a human vision, aware of values other than optical ones?

The Fighting Temeraire, J.M.W. Turner – 1839 – London National Gallery.

–

It is at this point that Eastlake jumps in to say that where photography may encroach on the territory of art, it is not actually the territory of art. She cites Rembrandt, Rubens and Turner as examples of where art manifests itself at its best. She even goes so far as to say that it is when photography is at its most crude, I believe thinking of the calotypes of Hill and Adamson who photographed it several times (image above), that it comes closest to being art.

Eastlake inverts the question and states, in a somewhat premonitory way, that photography would liberate painting rather than replace it:“For everything for which Art, so-called, has hitherto been the means but not the end, photography is the allotted agent – for all that requires mere manual correctness, and mere manual slavery, without any employment of the artistic feeling, she is the proper and therefore the perfect medium..” Or:“Photography is intended to supersede much that art has hitherto done, but only that which it was both a misappropriation and a deterioration of Art to do.“

The text is finally very witty, deliciously written and makes a good case for a somewhat romantic position of art where it would be safe from being invaded by new technology. It really is indispensable for anyone studying the history of photography and art.

The text is available online at this link: Elizabeth Eastlake, Photography

To close, and to give you more want to read, in case you haven’t already …

“Her business [photography] is to give evidence of facts, as minutely and as impartially as, to our shame, only an unreasoning machine can give.”