Steinheil is one of the great names in the German optical industry, even before the invention of photography. It all started when Carl August Steinheil (1801-1870) at the age of 22, gave up a career in law to devote himself to astronomy. He went to study mathematics in Gottingen with none other than the brilliant Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777-1855). In 1835 he became professor of mathematics and physics at the University of Munich and already in the 1930s he began to manufacture telescopes quickly gaining a solid reputation as an authority on the subject.

Carl August Steinheil (1801-1870), foto de 1850

Carl Steinheil was also involved in the development of technology for many other applications, such as the electromagnetic telegraph. What stands out, reading about his life, is that he was one of those restless and generalist spirits, like so many others in the 19th century, who, from a solid background in basic sciences, could not resist passionately attacking all questions, the most dispersed , that the scientific method could address.

Hugo Adolph Steinheil (1832-1893)

In 1852 the king of Bavaria, Maximilian II, asked him to settle permanently in Munich to dedicate himself especially to the field of applied optics (Corrado d’Agostini). I find interesting to look at these historical and biographical data to realize that although the pioneers of photography such as Nièpce, Daguerre, Florence, Bayard and to some extent even Talbot, were something of an amateur or dedicated hobbyist, photography soon became a scientific and economic subject that shook the political and academic world. The dilettantes did not disappear, many photographers, even those on weekends, contributed in different ways with inventions and improvements in the photographic process. But at the same time, the production of photographic images mobilized enormous energy from the great names of science, industry and political and institutional leaders. It is also interesting to observe this figure of the entrepreneurial researcher, scientist and entrepreneur, very common in the 19th century, but which today seems to have no place.

Maximilian II’s request made perfect sense because Munich had been the center for the development of optics under the leadership of the great physicist Joseph von Fraunhofer (1787-1826), but with the invention of photography, Vienna had become a strong competitor featuring names like Petzval and Voigländer, that were actually just the tip of a new iceberg that had quickly formed. Factories, raw materials, trade agreements, patents and also all the knowledge involved in optics, in the study of light, colors, chemistry, in short, an array of science fields, overnight, became the subject of political leaders, of kings and princes, who handled incentives, vied for talents and competed with each other for markets that opened up. They had to learn to move on that new board too. How much difference with the times, not too distant, when only wars could bring power and wealth to royal families.

But the name Steinheil goes far beyond its eclectic founder. For photography specifically, it is in the production of his son Hugo Adolph Steinheil (1832-1893) that we will find some of the main achievements that really marked the history of photographic optics in the second half of the 19th century. Adolph, did not get along very well with his father, as they had opposite characteristics. While Carl changed the subject all the time and started more projects than he could finish, it is said that Adolph was the persevering type and could not let go of a problem before finding its solution. It was this stubbornness that made him work 12 hours a day for 15 years, from the establishment of the firm in Munich, to develop a new family of lenses that would be a revolution in photographic optics (Agostini).

After Petzval’s lens, it can be said that nothing was as significant as the Aplanats, designed by Adolph Steinheil in 1866 (and simultaneously and independently by Dallmeyer, also German, working in England, who launched the same concept under the name Rapid Rectilinear ). Adolph had the collaboration of his friend, the mathematician Philipp Ludwig von Seidel (1821-1896), from the University of Munich, who had developed a set of equations that allowed to simulate the oblique rays falling on the lenses and thus to predict, with calculations only, the effects of each concept / optical design on the quality of the final image. Seidel was able to mathematically separate the different aberrations that deteriorate the periphery of a lens image.

Using this formalism that Adolph Steinheil was able to develop the concept of two symmetrical optics around the diaphragm and launch a line of lenses with different viewing angles and generous openings for the time, which reached up to f / 6. The advantage of symmetry is in the automatic correction of distortions. This was very important in architectural photography in which vertical lines appeared curved when using the landscape lenses available at the time. Another important use in which distortions were very troublesome was the reproduction of documents and maps.

The concept of Aplanats proved to be flexible and several versions, more angular and less luminous, for landscapes, or narrower in angle and more luminous, for portraits, came from the basic idea of symmetrical lenses. Not that symmetrical lenses were anything new in themselves, their advantages had been known at least since 1841, but Adolph Steinheil had the idea of using glasses in an innovative way. The doublets, to correct the chromatic aberration, until then were normally composed of a crown glass and a flint, but in Aplanats, according to Kingslake: “The real clue for the construction of Rapid Rectilinear [name of” Aplanats “in the design developed by Dallmeyer ] is in the choice of glasses. The two types should differ as much as possible in refractive index and as little as possible in dispersion index “. So Steinheil and Dallmeyer used two flint glasses that formed, among what was available at the time, the combination that allowed reaching that goal in refractive and dispersion indexes relation.

The Antiplanet

Antiplanet is another story, an alternative to Aplanat and bold in terms of optical design. The symmetry of the Aplanats eliminated distortions, but the image quality for distant objects suffered from aberrations and lost definition. Adolph Steinheil then decided to break the symmetry and set out to develop a design with four elements and two different groups. In 1879 he launched the Gruppen Aplanat with f / 6.2 and 56º viewing angle and still using the concept of doublets with flint glasses on both groups.

In 1881, not satisfied, he returned to doublets crown/flint in a way that one by one they had a horrible spherical aberration, but together, one made up for the other. The name Antiplanet was chosen to mean precisely something in opposition to the Aplanats for its breaking of symmetry. As for the design of the lens, there is a slight divergence in the sources.

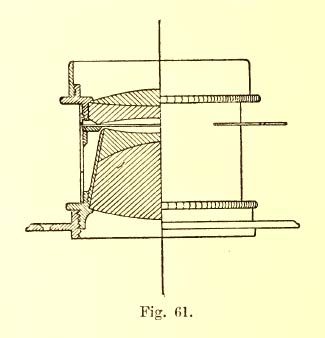

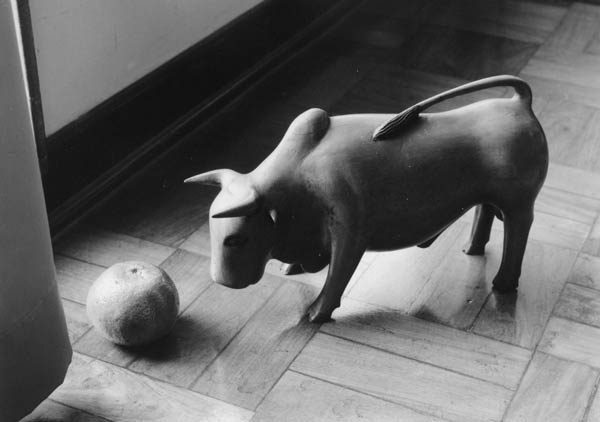

In Charles Fabre’s encyclopedic treatise of 1889, the Gruppen Antiplanet is presented as if its rear elements were conical (image above). This is different from what Eder presents us, drawing below. Kingslake comments that for Gruppen Aplanat, the rear elements needed to be tapered to avoid vignetting in the image. Judging by my sample, I would say that the doublet is really conical and probably to solve the same problem raised by Kingslake.

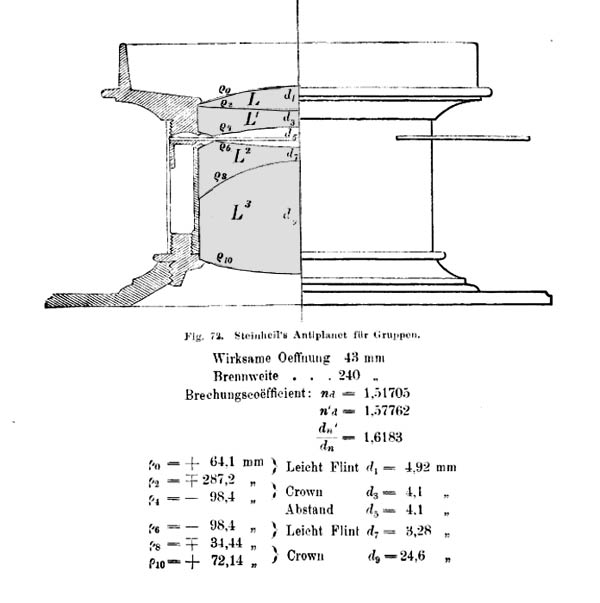

Drawing and measurements, Gruppen Antiplanet 240 mm (Eder)

Adolph Steinheil was also already researching the advantages of increasing the thickness of the glass and minimizing the air between the elements to reduce flare. At the Gruppen Antiplanet we have a minimal gap through which a diaphragm is inserted and the rear group windows form a really thick block.

Aesthetically, an optical glass block like this is very beautiful and impressive in one’s hands. The space between the groups is so narrow that when inserting the Waterhouse type diaphragm, it is not difficult to end up scraping the black varnish that is applied on the edge of the lenses, as seen in the photo above.

What was at stake in the development of Aplanats and after Antiplanets was the first really general-purpose lens in photography. Up until that time, only petzval-type portrait lenses, lenses for landscapes (that were simple achromatic doubles with the diaphragm in front) and some wide angles like Harrison’s Globe (1860) and Emil Busch’s Pantoskop (1865) were available to the photographer. These wide angle, which came close to 90º, offered only f/30 or f/25 apertures. There was no lens that was reasonable in all three aspects at the same time: in angle of view, in brightness and sharpness in the entire field of the image. Without such a lens, photography could not have amateur cameras with fixed lenses, not with the level of sensitivity of the wet plate collodion that was the method in vogue at the time. Gruppen, which means “groups” in German, would be that medium lens, between portrait and landscape, and could work in many situations. It would be the long-awaited general-purpose lens.

Photography has always depended on the simultaneous development of glasses, geometric optics and the chemistry of sensitive materials. Each time one of these three pillars went from one step to the next in its development, it eased the requirements for the other two. That was how even the meniscus, the simple, concave / convex lens, went far into the 20th century in popular cameras, thanks to the introduction of silver gelatin for which apertures such as f / 16 or f / 32 were no longer barriers to shooting in many situations.

Hugo Adolph Steinheil’s Gruppen Antiplanet, designed with the mathematical tools of Philipp Ludwig von Seidel, was one of the best possible achievements before new glasses were introduced, finally allowing the production of anastigmatic lenses whose mathematics was already known.

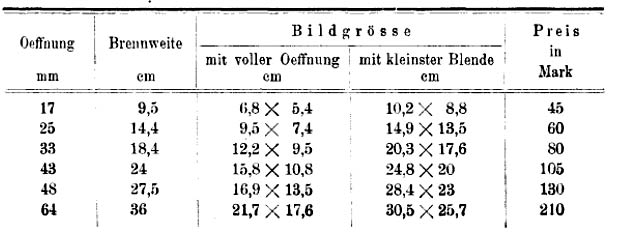

The table above shows the 6 sizes in which it was manufactured. This Gruppen Antiplanet is No. 4, has a focal length of 24 cm. The front element is 43 mm in diameter and is indicated with the measurement of 19 lines in Steinheil catalogs. Its aperture is f/5 and the viewing angle is 70º (Eder). The format is 15.8 x 10.8 cm with open diaphragm and 24.8 x 20.0 cm when fully stopped down, as seen in the table above. These measures are in general very strict and refer more to the area of sharpness instead of illumination. I have been shooting with it in the 13 x 18 cm format and apparently no fall-off. The geometric aperture is a little less bright than f/5, but at that time it was customary to adjust this number according to the amount of air/glass, glass/air surfaces in order to increase the aperture a little when the lens offered few of these obstacles to harnessing the incident light.

The serial number of this lens is 14,534, according to Agostini this indicates year of manufacture in 1885. On the body is written “Steinheil in Munchen No. 14,534 patent”. Unfortunately, Steinheil had a bad habit of engraving the lens name on the flange and, more unfortunately, many cameras were separated from their lenses without the flanges being removed from them so that they would remain with the original lens. As a consequence, today it is very common to find Steinheil lenses without a clear name that identifies them, because they are without the flange. In the case of this Gruppen Antiplanet this is less serious because its design is so distinct from everything that existed that it is easy to be sure of its identity. But with many Aplanat the issue can get quite complicated as many different types look alike.

In addition to not having a flange, this lens also lacked the Waterhouse diaphragms. Those that appear in the photo were calculated using this method and then printed in black ABS on a 3D printer. Without any diaphragm it has a 34 mm entrance pupil which gives it an f / 7 aperture. The smallest aperture I made, as seen in the photo, corresponds to f/32.

As if to compensate that it came without a flange and without the diaphragms, the general condition of the body, the varnish and the glasses are excellent condition and it is a great pleasure to shoot with this landmark in the history of photographic optics. The two photos below were taken in 13×18 cm format with Fomapan100 developed in Parodinal and printed by contact on Foma 111 paper.

Comment with one click:

Was this article useful for you? [ratings]