The decision

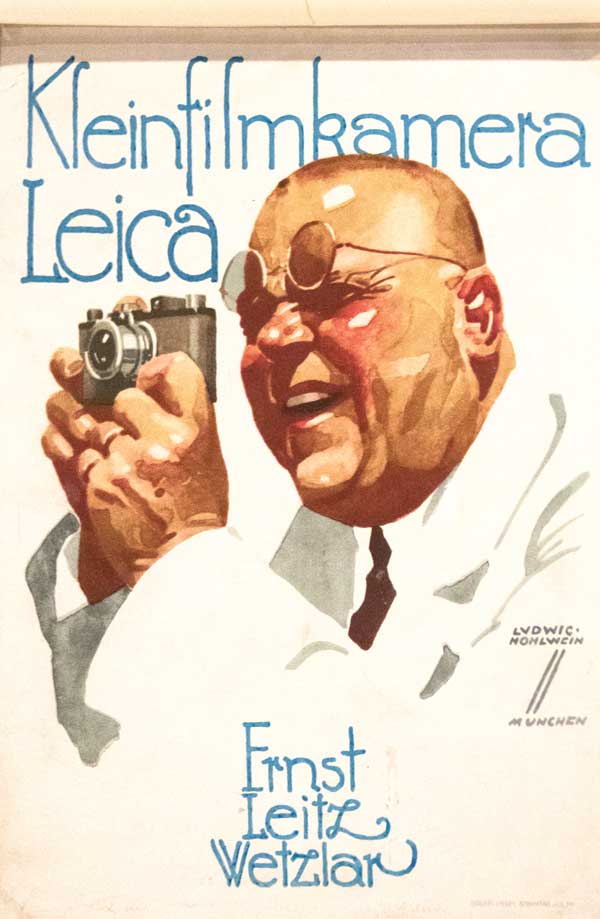

In this room we focus on the internal discussion that took place at Leitz about the launch of the camera that would come to be called Leica and that would change the course of photography forever. It is largely based on a chapter from the book 100 Years of Leica Photography, organized by Hans-Michael Koetzle. In an early chapter, written by Ulf Richter, there is a description of the meeting in which the sole owner and president of Leitz, Ernst Leitz II, gave his authorization for the project that would place the company in the hotly contested camera market. The interesting thing is that it allows us to understand the most important challenges that culminated in the launch of the first Leica at the Leipzig fair in 1925. After a long gestation that began in 1912/13, Leitz not only ventured into a sector in which it had no experience, but did so with a new concept that would put it ahead of the more traditional market leaders.

Leitz before Leica

Leitz was already a renowned manufacturer of optical instruments when the idea of extending its portfolio to photography was brought in by a new employee. Its history began in 1849 when Carl Kellner, a self-taught mechanic and mathematician, developed a new eyepiece for microscopes and started a company called Optisches Institut. Just six years later he died and the business passed into the hands of his widow. In 1864 Ernst Leitz I (1843-1920) came to work for the company, bringing experience in fine mechanics that included years in the Swiss watch industry. In 1869 he acquired all the shares in the company and changed its name to Leitz.

Leitz grew rapidly with microscopes as its flagship. In 1880, the company reached an annual production of 500 units. In 1887, it reached the 10,000th microscope, four years later the 20,000th and, in 1899, the 50,000th was completed.

It’s interesting to note that in addition to technology, the company knew how to promote its products and was very active in academic circles, where its main customers were. There was a policy of working closely with the most eminent scientists of the time, for example, bacteriologist Robert Koch received the company’s 100,000th microscope in 1907, Paul Ehrlich, inventor of chemotherapy, received the 150,000th, and Nobel Prize winner Gerhard Domagk, discoverer of sulphonamides, received the 400,000th Leitz instrument. This work with opinion leaders would later become one of the pillars of Leica’s promotion.

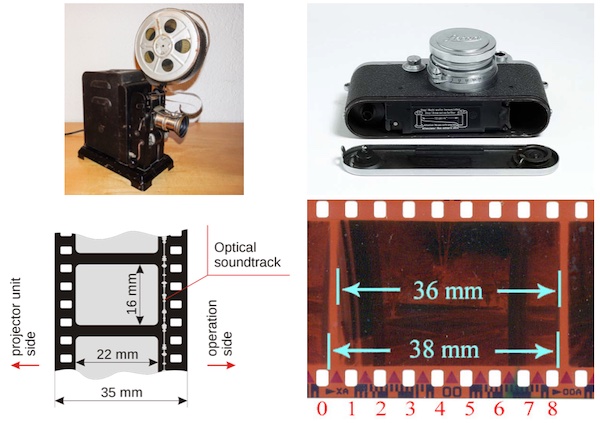

The economic situation had not been very favorable since the years before the war. It was precisely universities that had greatly reduced their budgets and difficult times lay ahead. Nevertheless, Leitz continued to invest in development and in 1913 launched the first binocular microscope. At the same time, they tried to diversify their portfolio and successfully launched projectors that they sold to schools. Ernst Leitz died in July 1920, and leadership of the company passed to his son, Ernst Leitz II.

In 1911, they brought in a new employee from Carl Zeiss in Jena to work in the development department. He was Oskar Barnack, then 31 years old. His hobby was photography and with his inventiveness and knowledge of mechanics, he was considering developing a camera from scratch. He thought of something totally different from anything else that existed. As we saw in the two previous rooms on the supply and profile of photographers at the beginning of the 20th century, professionals and advanced amateurs were convinced that good photography was difficult and laborious. Convenience was a thing for unambitious amateurs with their cheap cameras and poorly made photos. Oskar Barnack envisioned a camera that was easy to use but with the quality to take good pictures in a wide variety of situations. Leitz proved to be the ideal company for him to develop his project. Ironically, because it had no tradition in photography, it was not bound by any type of camera technology, system or format. The project began as something personal, but as it evolved it received support and resources from the company and resulted in a large business and a global brand of the first magnitude.

Micro Liliput Camera

The idea of using cine film for a photographic camera was not new. Leitz itself produced cine cameras and Dr. Paul Wolff points out in his book from 1933, “Meine Erfahrungen mit der Leica” that Oscar Barnack had worked on a small camera to test the photometry to be adjusted in film cameras, thus avoiding the risk of improper adjustment when filming. Also at Carl Zeiss in Jena, Barnack got to know the Minigraph, a camera developed by Levy Roth. It was a camera that made 18x24mm negatives. With the quality of film at the time, this format was too small and didn’t yield acceptable enlargements. It’s important to remember that the reference at the time was contact prints, which normally produce impeccable definition if the negative is good. In comparison, it is difficult for an enlargement from such a small negative to compete with a contact print at the already enlarged size.

The Minigraph looks very much like a cine camera and we can guess that the film runs vertically. Note that 18×24 is the format that today in photography we call half-frame and in cinema it’s full-frame.

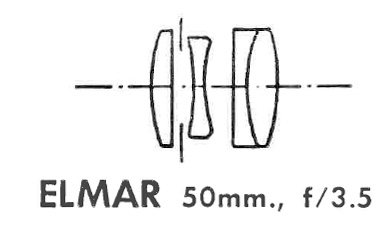

Oscar Barnack kept thinking about a small camera using cine film in photography. His first great idea was to run the film horizontally and thus double the size of the frame, adopting the 24×36 mm measurement, which is still the standard for 35mm film photography today and has become the full-frame we know in digital.

The standard that was created with Leica, and followed by all subsequent manufacturers who adopted 35mm film in photography, was to use 8 holes for each photo. That’s 38mm as we see above. But to give a spacing of 2mm between the frames he left it at 36mm. As a result, the width x height ratio was exactly 3:2, which he found aesthetically pleasing. The height of the film for photography is 24mm because it uses the whole band, while when used in cinema, there we find 22mm for the image and 2mm reserved for recording the optical sound.

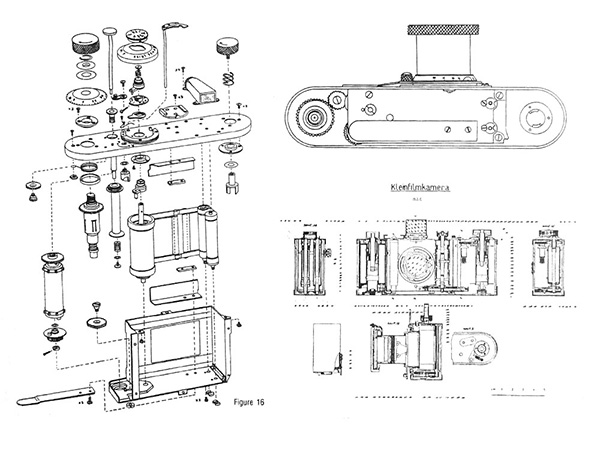

In 1914 there is a note in his diary “Micro Liliput cameras, ready”. Although the project was not immediately ready for launch, it is interesting to note that from then on, several improvements were discussed with other Leitz engineers, several tried out the Liliput Camera, made suggestions and several patents were registered. Although they didn’t feel it was time yet, resources were allocated to maturing the project and ensuring, through patents, that the innovations wouldn’t be copied if they were eventually leaked or coincidentally developed and registered by other companies. Some milestones in the development:

- 1920 – Max Berek designed a special lens for the camera with good brightness and sharpness.

- 1920 – A lightproof cassette was developed to hold enough film for 40 photos.

- 1921 – A rangefinder was developed and registered

- 1922 – The curtain shutter was cocked automatically every time the film was advanced

- 1923/24 – The shutter could now be cocked without the need to cover the lens (the curtains now passed through with a small overlap and therefore left no gap).

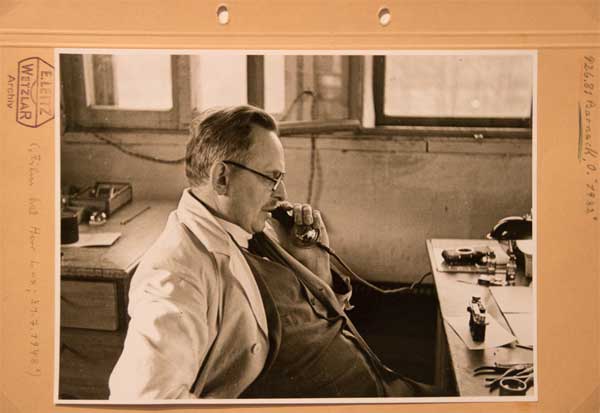

The 50mm lens

A very interesting point about this development, which has had an impact on the subsequent history of 35mm photography, is how the standard 50mm lens came to be. Everyone knows that the diagonal of a 24x36mm rectangle is 43.3mm. This would be the normal lens for the format, or at least something very close to it. But it turns out that, in the discussions between Oscar Barnack and the optician who was going to design the lens for Liliput Camera, Max Berek, certain conditions were mandatory and the 50mm focal length, as the standard lens, was the concession to accommodate these demands in the best way.

Barnack had experimented with the Mikro-Summar 42mm f/4.5, which would be great for the format, but he wanted a brighter lens, but Berek explained to him that with this 42mm focal length the 24x36mm required an angle of view of 53º and it would be impossible to get sharpness in the corners of the image if you forced an aperture wider than f/4.5. But sharpness across the whole frame was one of the points Barnack wanted, as well as a brighter lens, as films were very insensitive at the time. Berek calculated that with the optical glass available he could only design a brighter lens with a maximum angle of 48º. They could reach 52mm, that would be the focal length that would allow f/3.5, acceptable sharpness in every frame. But Barnack had one more condition, that the lens barrel could be retractable and go completely inside the camera. That was the condition for it to be a pocket camera, something he considered essential: to fit comfortably in his coat pocket. In the end, they closed it down to 50mm f/3.5 and collapsible. They called the lens the Leitz-Anastigmat.

Another important improvement introduced in the first specimens was to place the iris just behind the first element. This cuts off much of the unwanted light after the second surface and prevents part of it from entering into the other elements by reflecting uncontrollably inwards. The result was a considerable improvement in image contrast. A very important feature for a time when there was no coating, no anti-reflective treatment. The lens designed in this way was the Elmar 50mm f/3.5, a lens with 4 elements in 3 groups. It was thought as Elmax, perhaps by Max Berek, and at first it would be a 5-element lens, but it was recalculated to 4 and in the final version and they adopted the final R, as it had already become a standard for many manufacturers.

A curious fact about this development is that if Oscar Barnack, instead of wanting a collapsible and brighter lens, had chosen a normal lens for the format he himself created, the 24×36 mm, perhaps the Retinas, Contax, Exaktas and later Nikon, Canon, perhaps everything that came after, would have had as “normal” lenses something around 43mm instead of 50mm, which today we call “normal” but which is not.

By now, the project seemed very mature, some were enthusiastic and others remained skeptical, but it was clear that the time had come to decide: to launch or not to launch.

Pros and cons

The key meeting took place in June 1924 at Barnack’s request. Ulf Richter tells us that Ernst Leitz had not yet formed an opinion. At the meeting were the commercial, industrial and development managers. Everyone had tried out the prototypes and all had a favorable opinion of the small camera. Even some of the closest representatives and distributors were familiar with the project and believed in its potential.

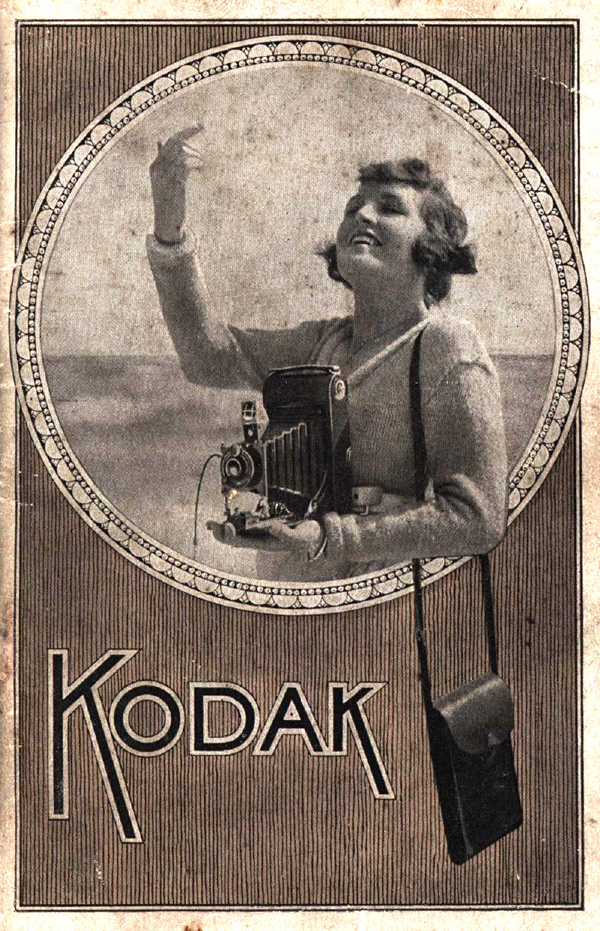

The Leitz representative in Berlin, Franz Bergmann, commented to Enst Leitz while leafing through a magazine: “Take a look at the advertisements. Can you believe that those girls smiling and holding those black cameras are really smiling? The design only reflects the manufacturer’s dream. Women would enjoy taking pictures if they had a little Barnack camera like this. After all, it fits in any handbag.” I found this remark funny because it immediately reminded me of the Kodak girls. Like the one below and … really, he was probably right.

Although opinions about the camera were favorable, there were internal challenges and great doubt as to how the market would react. Leitz had an excellent reputation among scientists and researchers, its projectors were also known to the general public, but it had no tradition in photography itself and the concept was entirely new.

At the meeting, Ernst Leitz asked August Bauer, the industrial director, to give his opinion. In short, he said that various operations in the assembly of the camera were too slow and that they would need more personnel with a different profile and adequate training. The camera, although small, consisted of around 200 parts. He said that although they normally verticalize production, they couldn’t do without external suppliers for some stages. One curious thing is that he says that the curtain and rods are sewn together and that “engineers can’t do that, that’s something for women’s hands”. It’s not clear whether this is a question of skill or something else. He gives a series of technical details and concludes that a small batch, with a good deadline and a high cost, could be done. He goes on to question whether the small format would be accepted. He thinks that in the cinema, with moving images, people don’t notice problems such as lack of definition and focus, but he believe that with a small negative the maximum magnification will be that of a postcard and people might not like that. An interesting observation he makes is that with a small negative, retouching is impossible and this can be another barrier with professionals.

To this Ernst Leitz replies: “August, these are not the buyers we have in mind. We can’t live off this small group and they can’t live with a camera that’s as expensive and elegant as ours. […] This camera will be bought by people who want a device with them at all times, so that they can photograph what their eyes see, what they want to record. They don’t want to order or plan a photograph. When the camera captures what they have seen flawlessly on film, they will definitely notice whether it is the camera or the film that has done it. Then the film manufacturers will have to, and they will, keep up. They will notice. […] Compact cameras are growing in demand. I’m sure of that.

The director of the optics division, Rudolf Zak, was more positive, but pondered that although the lens tested very well, with excellent results, it was very difficult to assemble. The two radii of curvature are very close together and it takes a long time to center them. He said they would have to implement tests during these processes to avoid too many parts being rejected once they were finished. Leitz asked Berek if there was anything he could change to make this easier. Berek replied that he would take advantage of a recalculation that was already underway to take care of this, but that the resolution needed to be maintained. He said that he had been to Dresden and Frankfurt a. M. and saw that films were being projected on bigger and bigger screens and so he was sure that this would put pressure on the film industry and that they would improve. “We need a million clear pixels on the 800 mm² of the negative [24×36=864], so that a focused image is projected when it is enlarged to a size suitable for viewing. The lens can do this, its resolution is well above that of film. I’m sure the films will be improved soon”.

In his speech, the last before Ernst Leitz gave his verdict, Oskar Barnack gives a perfect summary of the raison d’être of the Leica, still Liliput Camera, at that time: “Often the event has already passed when the photographer sets up his camera. He can’t create from memory as a painter does. Artistic photography that alters, retouches and embellishes until it only covers what the photographer or his client wants to see does not exploit the possibilities of photographic technology to the end. Photography is not painting. There are many people who just want to record what they are seeing at that moment. This requires a camera that is at hand and ready at a moment’s notice. This camera doesn’t exist yet, but it will and it will be this one.” He said, pointing to the prototype in front of him.

Barnack goes on to talk about the audience he believed he was addressing with his camera: “In addition to the [professional] artist photographer, there are more and more amateurs – and I’m just one of them. In Berlin there are a good number of clubs for amateur photographers with over 400 members. At the moment, throughout the German Empire, more than 140 clubs with over 4000 members are affiliated to the Association of Amateur Photoclubs.”

These advanced amateurs, members of photoclubs, as explained in the previous room, were precisely the ones who knew what a good photo was, knew about focus, speed and aperture, processed their photos at home, but only found large, clumsy cameras on the market, as we saw in the first room, if they wanted some flexibility of resources. The box cameras and their folding equivalents offered neither features nor practicality.

Ernst Leitz, as we know, decides on the release: “When I take everything into account, although I hear a few arguments against producing this camera, I see that these arguments don’t originate from the camera, but from the inadequacy of film and photographers’ loyalty to big, imposing cameras. But films are getting better, because cinema is gaining importance. We have to look forward. There are more reasons for than against it. Photography will perhaps also change as a result. If we don’t go now – I’m convinced – someone else will. I don’t think the risk is so great that I can’t answer for it. […] Mr. Barnack, please put some film in the camera for me, I’d like to try it out. I want to use it like an ordinary man and see if I made the right decision.”

That was in June 1924. The Leica was presented at the Leipzig fair the following year and was an immediate success. This account by Ulf Richter is very interesting because it shows the degree of awareness with which the Leica was conceived and launched. Barnack could simply have been creating a camera that he personally would like to own and use, and indeed he was, but he was also fully aware that the range of cameras on offer at the time did not match what a growing and affluent group of photographers would be looking for.

In one passage he comments on the Ernemann Bobette (later Zeiss Ikon), which was small and used unperforated film, but had the vices of another concept of photography that had already worn out. He notes that the film was advanced by turning a knob while watching the number of the next photograph appear in the window behind the camera. Anyone who has used these cameras knows that this is terrible. The window has a red filter and in the dark it’s impossible to see the number appear. In the Leica, the first camera with a film advance combined with a shutter release, the same operation was always done by turning a knob until it locked.

These details, which other companies might have considered superfluous, were essential for the new photography that was to emerge. With the cameras on offer in the 1920s, the time between deciding to take a picture and actually taking it was long, but everyone thought that was normal: photography was like that. Before leaving the house, you had to decide whether or not to take the camera with you, whether or not you were going to shoot, because the cameras were big and heavy. The Leica’s design, its small size, meant that it could always be in a pocket or bag and if a situation arose unexpectedly, the photographer wouldn’t lose it. Photography became much closer to simply looking. The camera, with the direct viewfinder offered by the Leica, became an extension of the photographer’s gaze. That was the concept and Leica was a master of execution. That was the reason for its success.

If you are in the themed circuit The Leica Revolution, use the buttons below to navigate through the rooms.