I. Introduction

II. Images as words

III. Medieval society

IV. The place of the bourgeois

V. Image Theater

VI. Petrarch and Humanism

VII. Bibliophile princes

VIII. The landscape

IX. Naturalism

X. The Portrait

XI. The good and the beautiful

XII. Conclusion

I. Introduction

When talking about art in the Renaissance, the much-used and abused quote by Leon Battista Alberti (1404 – 1472) in his De Pictura always comes to mind, where he argued that a painting should be as if its frame were the frame of a window through which we would observe a scene.

This undoubtedly points to an idea of “naturalistic” art, an art made to visually represent things that exist or supposedly existed. This may seem trivial, obvious, to those of us who are so used to photographs whose vocation is to make precisely this kind of image: to reproduce something that was in front of the camera, in such a way that the photo then functions like Alberti’s window.

But this little quote, this concept, is like the tip of an iceberg and there is much more to be investigated if we want to understand something that at first glance may seem like a paradox:

How did we get from a world that was highly hostile and suspicious of images to a point where they are omnipresent and we interact with them with the same detachment as we do with real objects?

We need to step back and make an effort to let go of some of our assumptions in order to understand how images worked in the Middle Ages and how they were transformed until we arrive at Alberti’s formula.

II. Images as words

Images were only officially and definitively admitted into the Christian Church from the 8th century onwards (Second Council of Nicaea – 787). Until then, they were a source of controversy because only the word, the text, was approved by Orthodoxy as a vehicle for sacred stories, the lives of the saints and their use in temples and liturgy.

There was a rejection of Antiquity, with its polytheism, idol worship and very sensual art, in contrast to Christianity, which looked down on the body and life on earth in favor of the soul and eternal life. Plotinus, a 3rd century philosopher who exerted an enormous influence on Christianity, said that it was shameful enough to have a body to represent it in a painting or sculpture that would probably last even longer (Tzvetan Todorov in Éloge de l’individu). Because of this outright rejection of images and its foundation in the scriptures, Christianity was referred to by the pagans as the “religion of the book”, i.e. of the word.

From the Second Council of Nicaea onwards, the image was admitted, but it entered the practice of Christian worship, in manuscripts and in churches, still somewhat as a “word”.

A “word” image is an image that refers more to the categories to which things belong than to particular things. A “word” image explicitly contains a collection of things, which have a name, are enumerable, recognizable, but with an economy of detail that reduces them to only their most relevant attributes. It usually functions within a narrative that it illustrates and enriches. But its function is ancillary.

Just as I can start telling the story of Little Red Riding Hood by saying “Once upon a time, there was a little girl who lived with her parents in a beautiful little house in a village surrounded by a dense forest”, in which case you won’t interrupt me by asking “what little house?”, ground floor or townhouse, brick or wooden, etc, etc, These details are not relevant to the story. If I were to illustrate it using images, a “generic” house, with a few “nice house” attributes, would work very well. It’s in this sense that I want to say that the images worked a bit like words.

On this page of the St. Paul’s Bible (c. 870), we have a scene from the history of the Israelites. Moses is blessing his people. He occupies a central position and the “people” are represented by opening an arch around him and are made up of a collection of heads all practically the same. There is no unity of time. Behind Moses, who lived in the 13th century BCE, are Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, who preceded him by five centuries. Moses himself appears three times, at the top on the right with his vision of the city of Canaan and then dead on the left. The buildings, the trees, bear no relation to the other elements in the scene.

It’s an image that lends itself well to telling the story of the Israelites, with a well-resolved composition that separates the different episodes in the same pictorial space and hierarchizes the figures. It has centers of attention and an expressiveness through the gestures of the hands that somewhat compensates for the platitude of the faces.

Above is a page from the Psalter of Louis IX, King of France, canonized as Saint Louis. It dates from 1260-1270 and was written in Latin. It depicts Noah’s ark at the moment when the dove returns carrying a branch in its beak. In this case it represents a precise moment in the narrative. But proportions are sacrificed in favor of understanding. What is important is to emphasize that it is an ark, hence the trapezoidal shape at its base. It is in the sea of the flood, so we can see its hull through the water, which is made transparent. It’s a sacred ship and that’s why its deck resembles a temple – the ark is the temple of God. Inside are specimens of the animals saved by Noah.

All these elements are important to the story and it would be very difficult to present them all in a realistic image. Psaltier’s solution forgoes any realism so that we can, one by one, find the attributes that make this image a narrative of the episode of the dove returning to Noah’s ark.

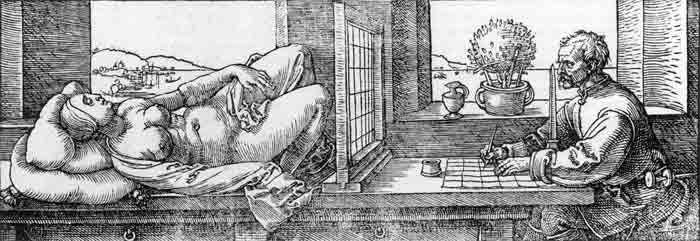

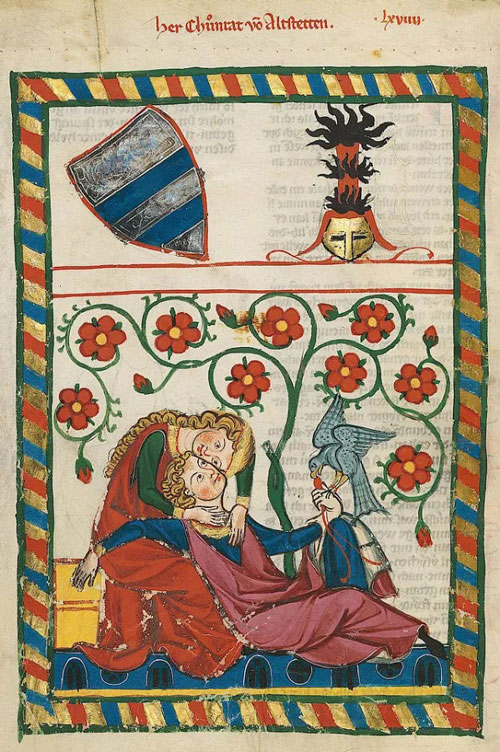

Now a pagan image, the Codex Manese – One of the main manuscripts of German art – 1310-1340 – Today in Heildelberg – Book of poetry with love songs. Throughout the work, the faces follow formulas with few variations and exhibit limited expressiveness. But the compositions and ornaments echoing the gestures of the characters give the images a very graceful melodic character. As a pictorial solution, this embrace of the girl in love, seen from this angle where the arms and faces stand out, one body bent and the other reclining, reveals great artistic refinement. What’s interesting is that the boy is not someone fictitious, he was someone known and identifiable, but not by his features. Instead, people were denoted by coats of arms, weapons, colors and mottoes, which is what you see at the top of the page.

The effort went into mastering the materials to create a plastic beauty, almost abstract in the sense that little concern was given to the actual visual appearance of what was being represented. It was ornament, calligraphy and preciousness that gave value to the final work. The image began and should end with the narrative for which it was intended.

Erwin Panofsky, in his book Idea, quotes a formula from Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) that highlights this approach: “Art happens on three levels: in the spirit of the artist, in the instrument he uses and in the matter that receives the form of his art”.

It should be noted that Dante simply doesn’t include the relationship between the appearance of what is represented and the image. It’s as if the object, the event, the scene, the person came out of the artist. He makes no reference to the referent. What the artist brought with his spirit, tools and materials was the image of a collective concept, not the image of something earthly and material. It wasn’t the image of something immanent, it wasn’t his personal vision, but a kind of symbolic and transcendent form of things.

III. Medieval society

It’s important to note that the production of images of the world of real, contemporary things was of no use to a conservative society based on tradition.

Everything they represented through images had a symbolic value, everything that existed had a symbolic value, they were part of a founding narrative and as such were more references to concepts than representations of their physical existence. Recalling Plotinus once again, in his philosophy that Christianity embraced, the world was taken as an imperfect version, engendered from a greater spiritual reality.

For this society, an art focused on the sacred stories of time immemorial and the military exploits of their ancestors was perfect for maintaining order in the world while awaiting the final judgment. It would be arrogant to value oneself as an individual. Humility was the great virtue and greatness was humbling oneself before God. It was a society focused on the past.

In this context, using the coat of arms and not the particular features of a knight to represent him, associated value with the lineage to which he belonged and not just with his person. What mattered was the title he bore and would pass on to his descendants, so that’s what was emphasized.

The nobles were military and ruled by brute force. The world was very violent. This military elite provided a certain order and protection from external attacks and was highly valued by a miserable population that was unable to defend itself. There are countless demonstrations of love and admiration that commoners had for kings and queens. The kings and their noble vassals actually went to the front and lived by the code of honor. They must be given that credit. Internally, succession disputes often led to them being assassinated even by their closest relatives.

Faced with a life that was not easy for anyone and that was still swept away by plagues and great famines after bad harvests, a certain peace of mind was due to the conformism disseminated by Christian ideology. The world is the way it is because God wants it to be and it’s not up to anyone to question, investigate or change anything.

IV. The place of the bourgeois

Europe in the first centuries of the Middle Ages was agrarian. So much so that, with the exception of clerics and nobles, the mass of the population was made up of rural workers in serfdom.

The serfs planted crops and raised animals on the land of others, usually nobles or high-ranking members of the Church. They paid for this use with part of their production. Not only could they not leave the property without permission, but a series of freedoms that we would consider basic today were forbidden to them, for example, marriages only took place with the permission of the lord of the land where they lived.

The cities were small and life was very simple, so manufacturing, commerce and services in general were in their infancy.

This changed over time and an urban population became part of the landscape. With them, a new character gained importance, the bourgeois, who ran small workshops, traded locally but also with distant lands.

Artisans and liberal professionals in the fields of law, medicine, accountancy and the like were also an important presence in the urban agglomerations that grew so much from the year 1000 onwards.

Curiously, for the contemporary observer, money could bring comfort but it didn’t necessarily bring recognition or honors. A non-nobleman, merchant, manufacturer, artist, freelancer or something equivalent, could become very rich, but on the day of the procession he would go after the squire, the lowest title in the military hierarchy.

No bourgeois would be the main character in a medieval literary play. Work per se did not make someone worthy and respectable. On the contrary, having to or wanting to work with one’s own hands, even if accumulating good wealth, was something dishonorable that indicated a lack of noble ancestry.

This bourgeois was neither a nobleman in cloak and sword nor a member of the religious organization. He didn’t get rich through tax collection or wars, like the former, nor through donations and spiritual services like the latter. But great fortunes were made from their proto-capitalist activity and this was a disruptive element in medieval social organization.

The Church preached that getting rich through work and boasting about it was sinful. God had given everyone their condition at birth and no one had the right to try to change it. The poor had to resign themselves to this condition because they were the chosen ones and the kingdom of heaven was already reserved for them. The princes, even with their wealth, were not exactly rich; they were stewards of God’s goods here on earth, because everything belonged to God. They were expected to be generous, so that they could help those in need in difficult times. They had to make sure that they didn’t succumb to the ultimate test of surviving in dignity, without sin, even in the deepest poverty.

For the rich, avarice was a mortal sin. But no one was charged with being generous to the point of complete bankruptcy. St. Louis was “for the poor”, famous for lavishly distributing alms… and at the same time he was the very rich king of France. His alms did not lift anyone out of poverty and in no way diminished his personal fortune.

All this mythology, in which life on Earth is just a preparation for the final judgment, may seem today to be an artificial argument aimed only at maintaining the status quo of those who were born into power and abundance. It would only serve to ensure domination over the people in general. But we need to be very careful here. We shouldn’t underestimate the penetration and authenticity of religious sentiment in all strata of society in the Middle Ages. Religion was taken seriously. The afterlife, where our soul would go, was an obsessive concern for everyone.

From the king to the squires, from the pope to the novices and all the servants and citizens of the kingdom, everyone lived their religious faith intensely, sincerely and without question. The order of the world was not a matter for humans because it was the fruit of God’s will. Questioning it would be an act of heresy and many died for straying from the right path. The tormented heretics are still proof of how intensely people lived their faith and many preferred the stake to reneging on the religious principles they believed in.

And what about the bourgeois? Well, he also lived in that same environment and system. He was also a God-fearing believer. With the exception that, just as for the people in general, this was an organization that didn’t suit him very much, because all the glory, power and recognition went to the exemplary secular or religious leaders. As for him, even though he contributed heavily to the construction and decoration of the churches, even though he financed the warlike endeavors of the princes, he was still just the bourgeois and had to bow down and revere leaders whose vices he knew so well because of his proximity.

However, unlike the people in general, he had the comfort, time and money to start asking himself if this was really how God wanted to see his earthly kingdom. Could it be that they weren’t all mistaken and that these preposters of divine power weren’t leading the whole flock in the wrong direction? Could the opulence of Rome and the greed of the princes be in line with Christian virtues?

Curiously, even ironically, in the clergy itself, especially in the monastic orders, some of the more daring minds also had time and bellies full to speculate on the official interpretation of the scriptures and the order of the world. It was by trying to understand Christianity in depth and studying the patriarchs of the church with great care that many of them strayed from orthodoxy. They didn’t want to reinvent anything, they were just looking for an authenticity that they believed the Church of Rome had lost.

It was these ramblings that fermented and fueled a revolution in the way the world was understood and the role of human beings within it.

V. Image theater

Parallel to this effervescence of ideas that took place in very closed circles in the midst of a basically illiterate society, an important transformation was taking place in the representations in images of the religious fact. The two things would come together later in the Renaissance.

The image as a word, as described above, gave way to an image as a visual impression. According to medievalists and art historians, experiments in this new approach proved capable of enchanting the faithful much more effectively than the ornamental, calligraphic images of the first centuries of Christian art.

Giotto di Bondone (1266 or 1271 / 1337) and Duccio di Buoninsegna (1255-1260 / 1318-1319) are usually cited as pioneers who wondered how the scenes in the Bible and other sacred narratives really took place and how they could best be presented in images.

These explorations would later result in what they metaphorically call “the invention of space”, in the sense that before the pictorial field was just the place where a collection of objects was displayed without them necessarily being articulated as a scene, as a certain event in a certain place, observed from a certain point of view. The collection was intended to tell a story, while the scene was the representation of an instant in that story.

In addition to this visual “realism”, the very poses, attitudes and angles from which the sacred characters were presented changed substantially. Until the 13th century, the Virgin Mary was depicted as a queen, appearing majestically to her subjects. But there was a distance between her heavenly world and the earthly world of the faithful who venerated her. The baby Jesus was small in size but had the proportions of an adult. To make him look like a baby would seem to demean him. There was a frontality, a rigidity in the hieratic attitude that could even be reminiscent, with the necessary reservations, of Egyptian or Mesopotamian statuary at the height of their empires.

The new realism wasn’t just about depicting the same poses with accentuated visual fidelity. The attitude of the sacred figures changed radically from an aristocratic pose to something denoting greater closeness, more humility, which would be more in line with a new interpretation of Christian precepts.

The madonna with a slightly tilted head and a kind gaze, without the distance of a queen, but instead seeking contact with the observer, was the convention adopted for a new relationship with the faithful. It is the archetype of the gentle, affable pose that guides most female selfies to this day.

From the 13th century onwards, there were many images in which she was like surprised by the artist, playing with her son, as any mother would. This humanization of the divine was intended to make the faithful feel a previously unknown empathy. In the ivory above, the Virgin Mary’s slight smile and fixed gaze on her baby no longer have any of the rigid pose of yesteryear. Her hands balancing the little body of baby Jesus on her knee makes the observer imagine what it is like to have this little life wriggling in his own arms.

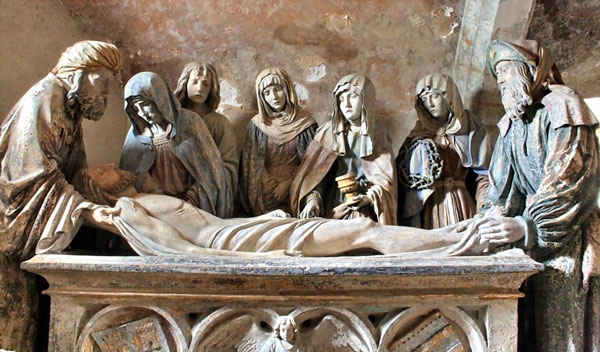

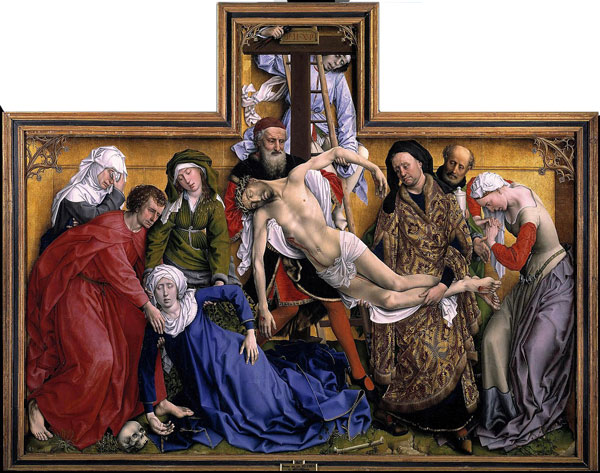

As a counterpoint to these images full of maternal tenderness, which activated the purest feelings of affection and admiration in the faithful, the scenes of suffering multiplied the commotion and moved them to tears. This is the case with the Deploration of the Christ, which represents the moment when the mother bends over the body of her dead son.

Or the descent from the cross, another landmark of Christian iconography that gained great visibility towards the end of the Middle Ages.

It was a radical change from what was done before the 13th century. It could be argued that as a religion, Christianity lost much of its otherness, its otherworldly nature or inaccessible mystery. But it gained in popularity and truly became a religion of the masses. The saints lost their haloes and lost that attitude that seemed indifferent to the torments to which they were subjected. Christ hung on the cross instead of miraculously floating in front of it and everyone began to express their sufferings and joys like any other human being.

The repertoire for these new attitudes meant a significant expansion of iconography. Émile Mâle, in his classic “Religious Art at the End of the Middle Ages in France”, discusses the origin of various scenes that artists incorporated or revised in this search for emotion and drama. The Nativity, the Adoration of the Magi, the encounter between Jesus and John when they were still children, the Deploration of the Christ and the Annunciation, among others, were incorporated.

Many of the new scenes are simply not described in the Bible. But they were inventions in works such as “Meditations on the Life of Jesus Christ” by St. Bonaventure. It’s even curious how Bonaventure’s pure speculation soon acquired the status of truth and scenes or long dialogues were incorporated into Christianity.

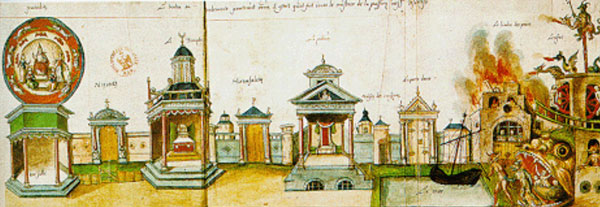

What’s even more interesting is that until they reached the illuminations and church panels, the new representations of the stories passed through the theater. Émile Mâle traced various elements in the verses of plays staged at the time. He mainly used decorative accessories and clothing colors as indices of the origin of the new iconographic element. For example, the lamp in St. Joseph’s hand in the nativity scene is described in the staged Passion and attests to the fact that the artists used theatrical scenes as a reference for their compositions.

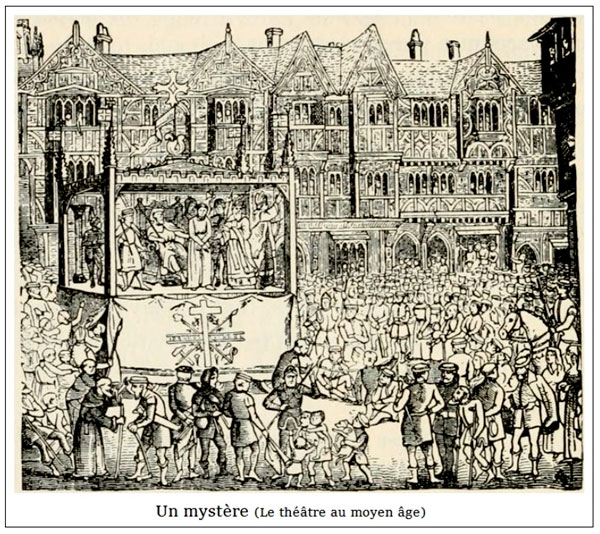

During religious celebrations such as Easter, the Mystère de La Passion was staged in France. Mystère has to do with ministry, as something public, so it would be a public presentation of the Passion of Christ.

These plays took between 6 and 25 days and involved around 200 actors, including professionals and ordinary people. Grandiose scenery and special effects were included to make the set lively. The actors took it so seriously that there are reports of even fatal accidents, with people being burned or injured by a more excited “Roman soldier”.

These reenactments had a huge influence on the design of the scenes depicted in the paintings. It’s not worth going into more detail here. But it is very interesting to note that the realism of the scenes and the dramatic gestures and attitudes that the artists depicted often originated in real scenes that they actually saw before their eyes.

By different routes, the concept of painting as a window onto a scene, which would later be formulated by Alberti, was in perfect harmony with the whole effort of religious art to appear real to the faithful. To the point that theatrical “scenes” were the references used for part of the new iconography, as Émile Mâle has shown.

But this realism, paradoxically applied to represent the religious imaginary, which in itself already meant a certain disenchantment of the mystery of religion, would still undergo a metamorphosis that would result in a fatal blow to the medieval conception of the world.

VI. Petrarch and Humanism

The development of urban centers and the flourishing of a population with the willingness and resources to speculate on other worldviews led to an investigation that would put an end to the ideology that had been in force since the weakening of the Roman Empire and the concomitant adoption of Christianity in Western Europe.

The medieval way of life, in which only knights and saints played model roles and rural properties formed a pyramidal geopolitical structure, with fiefdoms stacked in layers of suzerains and vassals, was not prepared to accept new ways of creating wealth and power, nor the formation of large national monarchies, which was already in its infancy.

It was mainly the unaligned, the bourgeois and liberal professionals, who didn’t live off their swords or their parishes, who began to look around and imagine other ways of organizing the world.

Louvre Abu Dhabi

When warfare became more sophisticated, with the widespread adoption of gunpowder in the 15th century, money, rather than the “number of souls” a feudal lord had, became a very critical factor for success. Wars needed to be financed and large reservoirs of money were in the hands of those who had no recognized political power in society. The nobility was the “government”, in the sense of decisions about laws, public administration, foreign policy, justice and many privileges. The distortion was that non-nobles were barred from becoming part of this government.

To give you an idea of how the nouveau riche annoyed the aristocrats of lineage, the Sumptuary Laws were enacted in several European countries from the 13th century onwards, but especially the 14th. These were laws that prohibited and limited the use of certain luxury items to dates, events and social classes, such as clothing with silks, precious stones, gold and silver and even certain colors that also denoted luxury. The aim was to prevent, for example, a banker from appearing in public with more wealth than the monarch.

This might suggest polarization, but this was not the case. There was no vocation, interest or tradition that allowed merchants or liberal professionals to enter into a direct conflict against the aristocracy in order to usurp or take over their posts. It wasn’t an “us versus them” situation where one side wanted to eliminate the other. Not least because aristocrats and clerics were the bourgeoisie’s best clients.

What this new power needed was to win an ideological war in which its way of life was valued. In the first instance, it would be a question of self-affirmation. The concept of honor was not yet linked to the idea of an honest life, a Christian life, respect for others and the things of the “good man”. That would only come much later. For the time being, honor was a matter to be resolved through brute force, courage and weapons. They needed a new worldview that would put an end to medieval cosmology.

This ideological turning point was consolidated in the transformations that we call the Renaissance. A key figure in this search for new worldviews was Petrarch.

Francesco di Petracco (1304-1374)

Francesco Petrarca (1304 – 1374) was born into a wealthy family but without any noble ancestry. His father was a notary, like a notary public today, and he wanted Petrarch to pursue a career in law as well, an aspiration he refused. Instead, he began writing in a wide variety of genres and soon gained prestige for his poems.

In addition to his authorial output, Petrarch was extremely important as a researcher in a new type of research. In the catalog of the exhibition The Invention of the Renaissance at the National Library of France in 2024, he is described as “the first manuscript hunter”.

In 1345, Petrarch found a collection of the letters of Cicero, a jurist, politician and philosopher from the first century BC, in Verona Cathedral. This discovery left a deep impression on him. Thus began an obsessive search for manuscripts and the reading, circulation and sharing of books, both ancient and those of his own time.

Petrarch formed and helped others to form libraries that had a universal character. He launched the concept of the public library, open to anyone who wanted to do research in it. Although he didn’t succeed in his lifetime in creating this absolutely innovative space for the time, his influence led to the first open libraries appearing in the 15th century.

“Hunting”, reading and studying manuscripts by the great philosophers and poets of Classical Antiquity was, for Petrarch and his “network”, like discovering hidden treasures in the dusty archives of monasteries and palaces. Some accounts of these finds even have an adventurous flavor and attest to the excitement that these ventures gave rise to.

For centuries, the attention given to this repository of past achievements was very limited. Classical Antiquity and its achievements have always commanded respect and admiration from Roman Church scholars. But they didn’t try to extract a new order from them; on the contrary, they sought to harmonize their achievements with the foundations of Christianity. Just as they tried to demonstrate that the advent of Christ was already pre-figured in the Old Testament, they also looked to Greek thought for a role of antecedent, of coherence with Christian cosmology. This is what explains why this pagan heritage was kept and preserved, as has been seen in this late rediscovery, now in a new light.

But this was just as well, because in Europe there was a feeling of exhaustion at the endless exegeses on the same old books and authors, starting with the Bible itself. If, on the one hand, faith in the religious foundation was very much alive, on the other hand, the Roman Church, as the official spiritual leadership, already had a scorched image of corruption and sheer greed for power. As mentioned above, the representation of the world that this body of knowledge reflected was no longer adapted to the transformations that took place from the 13th century onwards.

Also from the exhibition catalog at the BNF, Guido Cappelli makes the following comment: “The classics [authors of Greco-Roman antiquity] provide a response to the crisis of traditional disciplines, the decline of knowledge, the hegemony of ecclesiastical power and the dominance of new perspectives of ascension and social recognition: everything that was part of the underlying movements that gave birth to Humanism.”

The discovery of manuscripts of natural sciences, philosophy, theater, epic poems, all from the distant past, all so well written, with style, with resourcefulness, with audacity, gave the Humanists the stimulating certainty that knowledge could also be the fruit of speculation, of human creation, of organized, well-conducted thought, in short of the “dare to know”, as Emmanuel Kant would say 400 years later.

What delighted and inspired the Humanists was to see, through the example of Classical Antiquity, that there could be knowledge independent of the Church, knowledge prior to and ignorant of the scriptures, knowledge beyond theology.

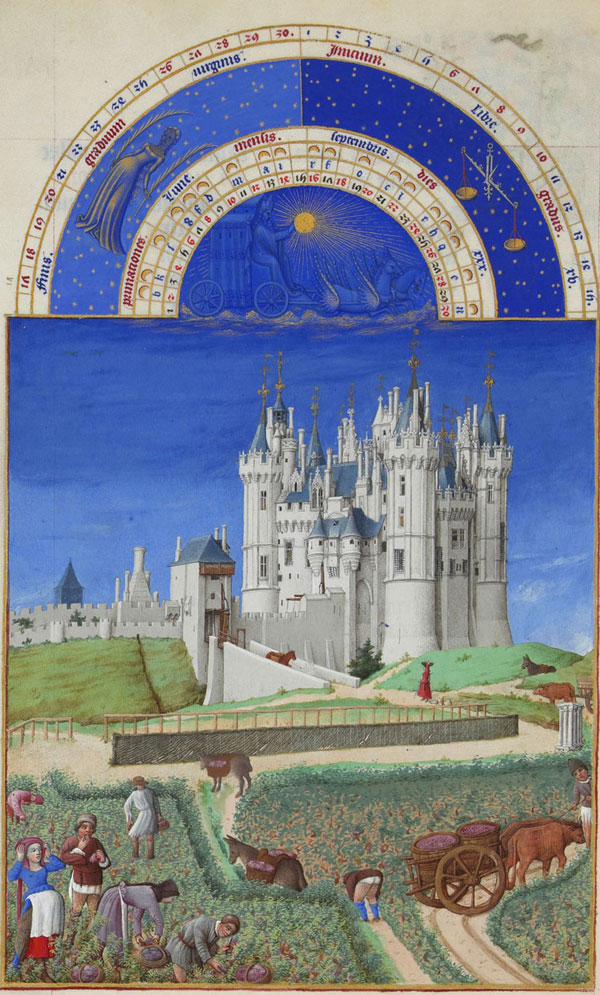

VII. Bibliophile princes

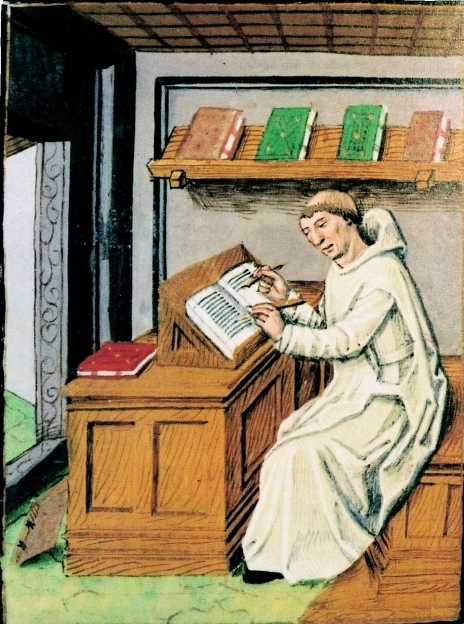

Just as the digital revolution incorporated new objects into our daily lives and new spaces into our homes, the dissemination of books by the nascent humanist culture called for solutions that didn’t exist in castles to accommodate the new habit. The studiolo, an Italian word, came to meet this need. It was a small room, using a lot of wood for the walls and furniture, probably to make it cozier, especially in winter, and furnished with typical office furniture. It was a place of seclusion, intended for reading and meditation.

It wasn’t something totally new, as monks’ cells had long existed in monasteries as a space for reading, study and prayer. But while the cells also functioned as dormitories, the studiolo kept the aspect of solitary retreat, but was exclusively intended for intellectual activity.

This rediscovery of the secular book we can now retrospectively associate with the desire for profound changes in society. But on an individual level, for those who created and decorated their studiolos and later libraries, it was undoubtedly based on the forgotten, or until then entirely unknown, possibilities that a good book could offer for the simple pleasure of reading it. In his “Solitary Life”, Petrarch wrote:

“I’m also looking for books of various genres which, through their authors or their themes, are pleasant and faithful companions: ready, at your command, to leave or return to their shelves, always willing to remain silent or, speak, stay at home, accompany in the forest, travel far, live in the country, talk, joke, exhort, console, warn, convince, advise, teach the secrets of things, memorable actions, the rule of life and contempt for death, moderation in prosperity, courage in adversity, constancy and firmness in action; cultured, cheerful, useful, talkative companions, whose presence does not arouse boredom, embarrassment, complaint, murmuring, jealousy or deceit; among these advantages, they do not demand food or drink and are content with poor clothes, a corner of the house – without, however, failing to offer their guests inestimable riches of soul, vast residences, dazzling clothes, banquets full of pleasure and the sweetest dishes”.

But without discrediting the seductive power of the book, for all the wonders it offers, so intensely sung by Petrarch in the lines above, the voracity with which the nobility began to dispute among themselves the formation of libraries with the richest illuminations and the rarest manuscripts, perhaps also finds a good argument in the vision of Erwin Panofsky in his “The Flemish Primitives”:

“Extravagance in manners and customs often coincides with periods in which the ruling class of an aging society begins to feel threatened by the growth of younger forces opposed to it […] The old feudal aristocracies experienced the need to assert themselves not so much to growth as to the de facto intrusion of a new proto-capitalist class of merchants and financiers. The result is what we can call an inflationary spiral of social ostentation”.

At the end of the Middle Ages, one of the categories where the bourgeoisie and the nobles in cloaks and swords began to measure forces was in the area of culture, in the works of art they possessed, in the architecture and decoration of their palaces, in the stature of the artists and intellectuals who frequented them, in short, in their spiritual refinement treated as a patrimony and a symbol of power.

In the “spiral of ostentation”, libraries scored many points. The largest libraries, at the end of the 15th century, had 600 or even 1,200 books, both religious and secular, on the most diverse subjects.

At the end of the 15th century, books were even coveted as spoils of war. The looters searched for treasures in gold, precious stones and saints’ relics, but they also went to the libraries in search of books.

Prince Federico da Montefeltro and his Son

1480-81

It is this setting that made possible an unusual painting like this one by the Spaniard Pedro Berruguete depicting Federico Montefeltro and his son Guidobaldo. Montefeltro was Duke of Urbino, a condottieri, a mercenary, feared for his skills at arms, but also a humanist intellectual who set up the second largest library in Italy. The first was in the Vatican.

There is something unusual about the scene. It’s a profile, but a full-length one, so it’s not in the tradition of a heraldic portrait focusing only on the features of the subject. Montefeltro is distracted in his reading, he doesn’t have the usual impassivity of a princely portrait in which the protagonist faces us with his distant, superior air. But it’s also far from being a snapshot of everyday life, because who would put on full armor to read a book? The scene only makes sense because it brings together these two sides of the character: intellectual and warrior at the same time.

But with regard to Italy, it’s important to draw attention to something special when compared to the rest of Europe. Precisely because of its leading role in giving life to Humanism and inducing the Renaissance, with all its achievements in the arts, we must consider that its starting conditions had some idiosyncrasies.

In the early days of the Renaissance, Italy was a patchwork quilt with a multitude of political units that formed a wild geopolitical eco-system. In his classic “The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy” (1860), Jacob Burckhardt ponders that “the conquests and usurpations that had hitherto taken place during the Middle Ages rested on real or fabricated rights from a supposed past or were directed against unbelievers and heretics. Here [Italy in the 14th century] for the first time, the onslaught was openly directed at conquering a throne by wholesale murder and endless barbarity, by adopting any means and with the sole focus on the intended ends”. To the archetype of the feudal lord with his lands inherited from distant generations and stony duties of vassalage to the king, as was more the case in France; or to the typical bourgeois, with his commercial leagues, guilds and banks, as in Holland, in Italy was added the condottieri, an upstart in arms who offered his services to the highest bidder. These often founded their own principalities and started new lineages with palaces, fortifications, churches, grandiose tombs and aristocratic titles.

It’s ironic, but this extremely unstable, violent, often sadistic and merciless environment, with the most barbaric executions, massacres, pillages, bloody attacks and fratricidal murders, was very fertile for cultural development. Such an environment could only be extremely individualistic, and individualism is a basic ingredient of Humanism. Burckhardt also argues that it was precisely the lack of legitimacy that led the despots of the time to opt for grandiosity as an instrument of self-assertion. In addition to brute force, luxury, patronage and erudition were ways of giving materiality, of giving an almost mystical basis to his power. In the midst of a miserable population, ostentation even functioned as an indication of a divine connection, which the Church did not refuse to endorse.

It was along these lines that Humanism gave intellectual activity an appreciation totally foreign to the Middle Ages. Any inclination to seek knowledge in the secular sphere of society was discouraged, devalued and even suspected. The Bible itself was primarily a matter for the clergy and the faithful had to be content with the official interpretations they received orally. Only a relatively small part of the population had access to some manuscripts and most of them were prayer books.

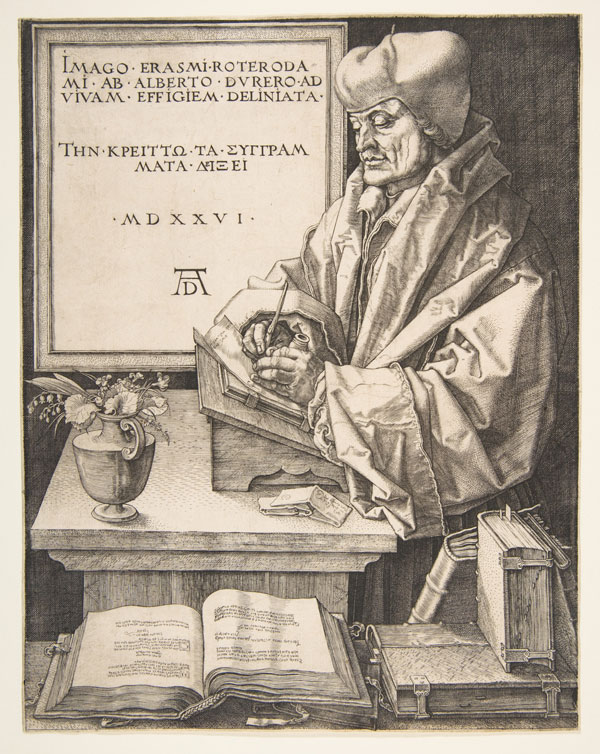

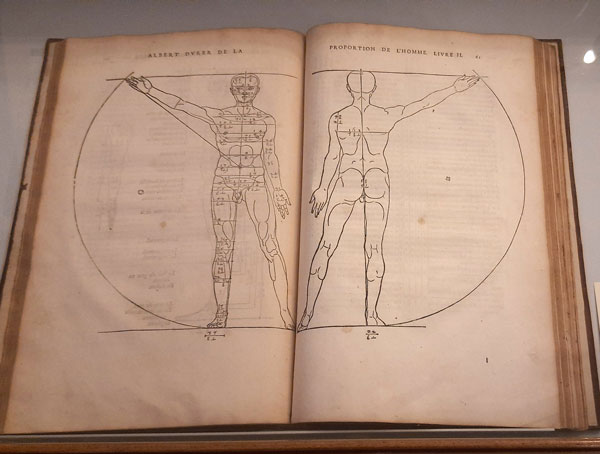

At the beginning of the 16th century, a major change took hold. In addition to the pious posture of the religious or the haughty posture of the warrior, a new type of ideal was coined in the “wise” attitude of the intellectual. Artists took it upon themselves to materialize, in gestures, poses and looks, what the vision of someone who possessed knowledge of the world would look like and who was able to point out new paths to salvation. A new type of hero was born with Humanism.

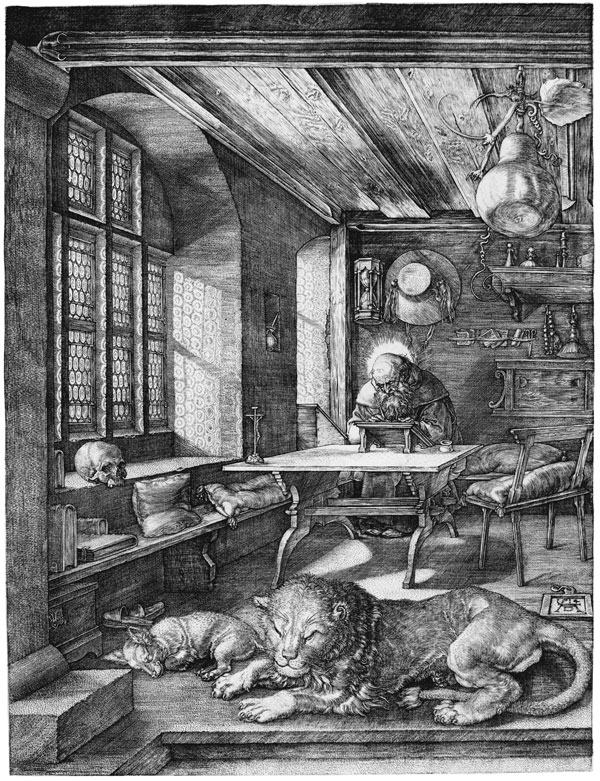

Ironically, we can also see signs of a certain fear of this new adventure. An icon of the link that can be made between the intellectual emancipation of humanism and the fear of abandoning the solid foundations of tradition is the famous engraving Melancholy, by Albrecht Dürer (above). A winged female figure is shown in an attitude of lassitude while surrounded by objects linked to alchemy, numerology and geometry, among others. She can fly but is heavily grounded. The atmosphere is reminiscent of the copious studio of St. Jerome, above, by the same Dürer. But while St. Jerome seems to be working hard, the muse of melancholy seems to want to show us that knowledge and autonomy are not necessarily the key to happiness.

In the same direction, but even more drastically, this melancholy would be revived by 19th century Romanticism. On the morning of the Industrial Revolution, artists would deny the achievements of the Renaissance and the glorious century of enlightenment that followed it, and would nostalgically turn their eyes to the certainties of the Middle Ages.

VIII. The landscape

If we had to represent the Renaissance as a gesture, I think the best way to express it would be to raise our heads. In the Middle Ages, beautiful things were created and the ideal of a religiosity of temperance, love and generosity was lived out intensely. But in practice it was also extremely violent and averse to change. It was a time of hierarchy and submission.

For centuries, heads have been bowed in prayer, disinterested in their surroundings, fixated on a spiritual world far away from here. The real world was just a symbolic manifestation, hermetic and inaccessible to ordinary people. The Catholic Church’s manual for life was very clear: resist sin, resign yourself to your fate and await the final judgment.

The humanists of the Renaissance dared to raise their heads and look around. What did they see? They saw the world, the landscapes, the plants, the animals and the stars. So obsessed with obeying God, they realized that they hadn’t looked at his great work, the world we live in, for a long time.

An adventure by Petrarch, who climbed the 1912-meter Mount Ventoux just to see the landscape, to feel the different air, caused a lot of astonishment and was much talked about. It’s hard for us to imagine but people “didn’t see”, they didn’t have this concept of admiring a valley, a mountain or a river. As an autonomous pictorial genre, the landscape was invented in the Renaissance.

By raising their heads and looking at, trying to understand and admire nature, the humanists saw a path there, the possibility of a kind of asceticism outside of orthodoxy, outside of traditional theology. They weren’t atheists. They believed that the creator’s will was certainly impregnated in every corner, in every detail of his creation, so they saw the study of nature as the path to understanding and communion with the divine. Studying and understanding nature became an act of devotion. It would be the primal source of truth. A fountain from which anyone could drink.

About this change, there is a passage in Leonardo da Vinci’s notes that is very enlightening: “I am fully aware that the fact that I am not a man of letters may cause certain arrogant people to think that they can rightly reproach me, claiming that I am a man ignorant of book learning. Silly people! Don’t they know that I could respond by saying, as Mario did to the Roman patricians: ‘Those who are adorned in the work of others will not allow me my own’? They will say that, because of my lack of knowledge of books, I can’t adequately express what I want to deal with. Don’t they know that my subjects need, for their exposition, experience rather than the words of others? And since experience has been the teacher of those who write well, I take it as my teacher and always turn to it.”

Leonardo was a bastard son. His father, like Petrarch’s father, was a notary and therefore had a comfortable social position. But his mother came from a very humble background. For this reason, he would never have been able to attend university and become a “man of letters”. Luckily, his grandfather (or a paternal uncle) provided him with a basic, private education to learn to read, write and do mathematics. For someone like him, that was enough.

His writing shows his resentment of prejudice, of the barriers that someone in his condition would encounter if his talent were to be appreciated. So he chose the observation of nature as his source of knowledge. Both for his painting and for his many studies bordering on the scientific. He chose experience as his method. He chose an open, independent path, even for those who didn’t belong to the elite of the time.

What’s even more symptomatic is that he looks for an example, a comparison, in Classical Antiquity, in Gaius Marius. This is the result of the work of the “manuscript hunters” who gave access to the pagan, pre-Christian world. Gaius Marius (157-86 BC) was a Roman general and statesman who, like Leonardo, did not have the support of a noble ancestry and his military skills aroused admiration but also opposition among the Roman patriciate.

Raising one’s head, looking at the terrestrial world and taking nature as the great teacher was the attitude that led Renaissance art to naturalism. They thus arrived at Alberti’s formula: the painting as a window, the autonomous and infinite space is the realm of Nature. The act of observing her made linear perspective possible as a method of representation that finally created space as we understand it today.

This same outlook would lead us to the scientific revolution and the Modern Age. Interest in nature and, above all, the idea that it could be investigated, curiosity about its mechanisms and the richness of its endless forms of life and phenomena, once again became the subject of intense research.

Publications chronicling the wonders of nature flooded the libraries. Books of hours, psalters, bibles and other religious publications had the preciousness and exclusivity, the intense, almost insane work involved in their production, as an offering and an object of devotion. In contrast, the invention of the printing press by Gutenberg gave primacy to the content and circulation of new ideas.

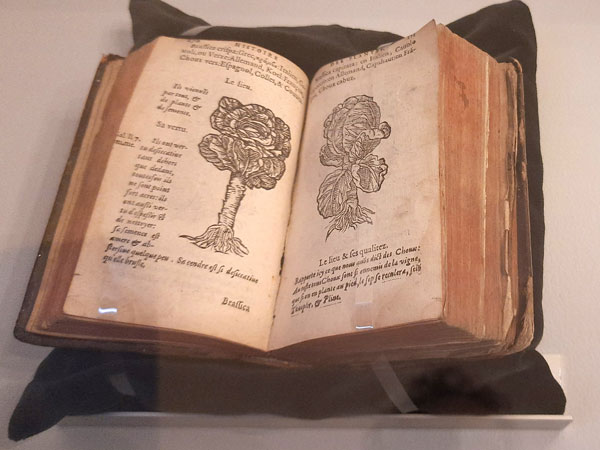

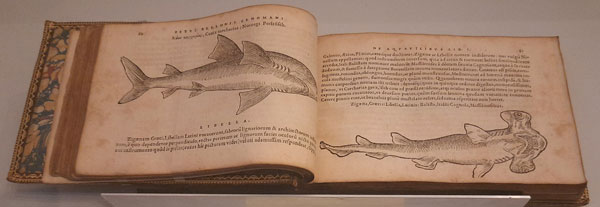

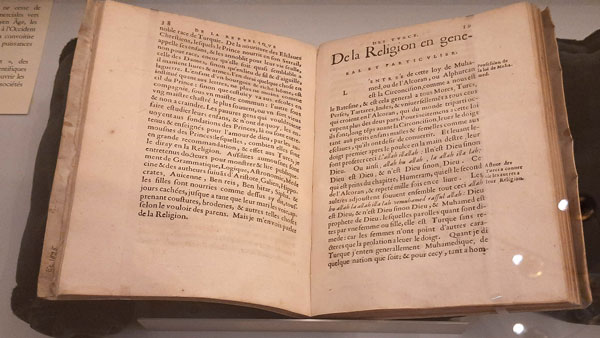

The images above are of books on display at the Chateau d’Écuen in France, home to the Renaissance Museum. They are examples of the breadth of topics that came to interest the intelligentsia of the time. Much of this type of inventory and classification research had already been done in Classical Antiquity and more recently by the Arabs. But in Christian Europe it was absolutely new.

Something worth highlighting and which is unprecedentedly bold is that even religions have become the object of study. Religions are first and foremost, in their deepest nature, the manifestation of a superhuman power or powers. The comparative study that this book seems to propose is the very negation of religiosity. It moves religions into the field of culture, of “beliefs”, of folklore and therefore of human creations.

Going through Leonardo da Vinci’s notes is another way to get a clearer idea of how far this discovery of nature went. We find topics such as: why the voice becomes thinner in the elderly, what our veins are, the sound that remains in the bell after it has been struck, what the moon is, why the sun appears larger in the west, how light penetrates liquids, the origin of rivers, the movement of birds under different wind conditions, what makes waves in water or why the tops of mountains appear darker than their bases.

It was therefore in the space of a few decades that the world ceased to be just a waiting room for eternal life, in grace or damnation, and was rediscovered as if it were something new, fresh and fascinating.

IX. Naturalism

The search for empathy with the faithful, through greater dramatization in Christian iconography, added to the humanists’ enthusiasm for the real world, converged in the valorization of naturalistic, visually convincing art.

Naturalism here did not yet mean the representation of everyday scenes as if they were photographic snapshots. That was to come, but later. Naturalism meant that a face, a torso, any object should be rendered with the correct proportions, seen from a certain angle, with coherent shadows and volumes.

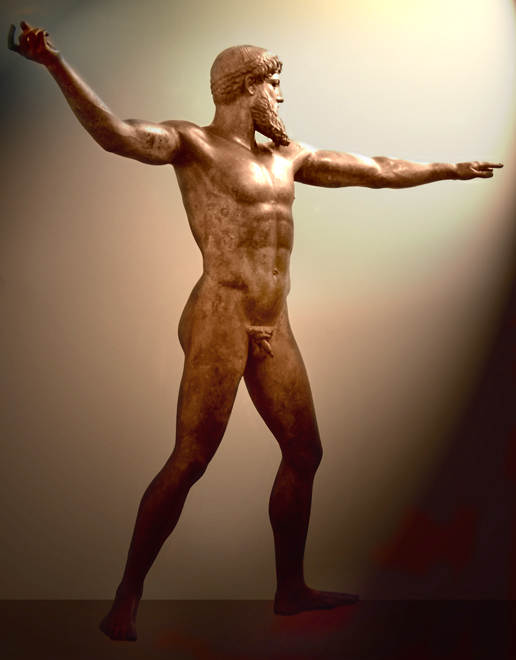

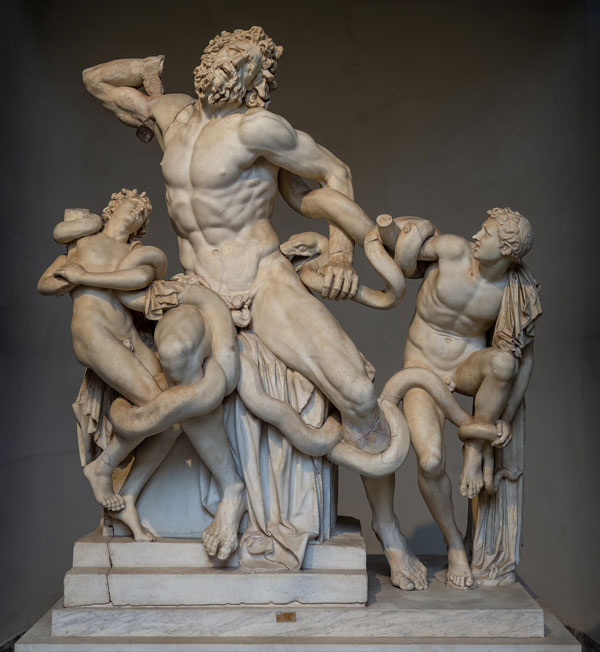

With this goal in mind, they studied Greco-Roman art extensively, as they understood that it had achieved great mastery in these matters, especially with regard to the human figure. It’s hard to imagine the stupor that must have been caused in 1506 by the excavation that brought the Laocoonte group to light. This group relates to a legend of the Trojan War and shows Laocoon and his two sons being strangled by a serpent. The vigorous bodies so well modeled, the complex composition, the vivacity of the drama and the difficulty of execution was everything that the artists of the 1500s wanted to be able to do as well. It must have been very strange to confirm once again that someone had already reached this level of perfection in such remote times.

But as we’ve seen above, the objectives of medieval art were different. It’s interesting to compare, through a common theme, how the artists’ choices changed until the rapprochement with Classical Antiquity.

This mosaic depicts the Holy Supper. It dates from the 6th century, right at the dawn of Christianity, and is located in the Sant’Apollinare Nuovo basilica in Ravenna, Italy. The artist chose a table in a semi-circle. He placed Christ on the left giving his blessing and he appears as if reclining on a bench. His body is mirrored by the last apostle on the right to give symmetry and balance to the composition. For the sake of understanding, the fish on a platter are seen from above, while, incoherently, the characters are seen from the front. With the exception of two of the apostles who have white hair, the others are serialized in the same formula to represent their faces and hair.

It’s an image that aims to make the scene recognizable through a schematic representation of only the key elements, while still providing a sober and pleasing aesthetic effect.

Eight hundred years later, in the Holy Supper by Ugolino di Nerio, a follower of Duccio di Buoninsegna who was therefore already concerned with a more visual representation, we have a notion of perspective that is evident if we look at the ceiling of the room. But the table still seems a little too tilted to be able to show what’s on it. The plates, which are probably round, retain this shape even when viewed at an angle. So let’s say that perspective was still sacrificed in favor of understanding.

The moment chosen, rather than being a blessing, is more dramatic. It’s the moment when Jesus says that one of his chosen ones is going to come out and betray him. Ugolino gives a clue as to who he is, because he is the only apostle without the halo of a saint. There is no attempt to indicate by his expression or posture that he is Judas. He is portrayed in the same neutral attitude as any of the others.

Despite the more natural arrangement, going around the table, the positioning of the halo is a little strange in the case of the saints to the right of Christ, as it seems to be an obstacle to conversation with the guests on the other side of the table. But in fact their presence is only symbolic and not physical. They only function as markers of holiness and are therefore made of gold leaf.

The faces of the apostles are much more individualized than in the previous example, with hair, beards and features that follow a looser scheme and allow for some differentiation. But their poses, in general, still show serialization and little of their bodies can be seen beneath their garments.

Now let’s look at Leonardo da Vinci’s Holy Supper. He chose to place everyone on the same side of a long table, thus offering the viewer a panoramic view and creating more space to work on attitudes. He removed Christ from the headboard and placed him in the center. He introduced a landscape seen through openings at the back of the room. The moment chosen was again the one in which Christ announces that he will be betrayed. The table is shown with some objects on it. Let’s now turn to the points that make this Holy Supper a Renaissance painting.

To start with the obvious, we have a perfect linear perspective. Not only is it perfect, it has been put to the service of emphasizing Christ through the many parallel lines that converge on him. He gave each apostle a personality with different features, gestures and clothing, but organized with a kind of visual musicality that makes our gaze move seamlessly from one gesture to the next. The tension associated with the revelation of the betrayal allowed the artist to explore the different reactions and interactions between the characters.

The absence of haloes was nothing new at the time, nor was the addition of a landscape seen through openings at the back of the room. But these are elements that help anchor the painting as something happening here, somewhere, like a terrestrial event.

Nothing there was done without preliminary studies and each pose was decided from among many possible variations. This rhythm in the gestures and the didacticism of the composition, while still guaranteeing a great naturalness in the scene in general, was the fruit of a lot of experimentation and analysis. Medieval artists knew very well how to be didactic in telling their stories, but they sacrificed naturalness in order to do so, producing images that began to seem crude and unconvincing to those who wanted more emotion. At the turn of the Renaissance, both clarity and naturalness became requirements for a successful work of art.

An interesting point about preparatory studies is that they have come to be kept, sold and collected. This reflects a new way of looking at them as something closer to the creative act. Because of their somewhat erratic and unfinished finish, the studies can be metaphorically linked to an “idea” in the midst of conception. The work was in the artist’s mind and the studies would be its first manifestations in the real world. This view corroborated something that was very important to artists like Leonardo da Vinci. He wanted everyone to see the visual arts as an intellectual, mental activity, and therefore deserving of the same deference as the so-called liberal arts, which are made up of the Trivium (logic, grammar, rhetoric) and the Quadrivium (arithmetic, music, geometry, astronomy).

X. The Portrait

In his book “Éloge de l’individu”, Tzvetan Todorov says that the Renaissance was more the discovery of the individual than the discovery of Antiquity. It was an emancipation of the particular from the category to which it belongs. The emancipation of the person from their clan or class. It was the valorization of the instant lived, of the passage of the present time, over eternal life. It was the individual’s claim on their destiny.

In this context, the portrait was promoted to one of the most important genres in painting. If before a coat of arms said everything that needed to be said about a character in an illuminated manuscript and the representation of the individual themselves could well be just the indication of the same by some formula, as we saw in the Codex Manese above, now the search went on for the features of the portrayed in the fullness of their realism.

We can metaphorically imagine that the entry of nobles and bourgeois into painting at the end of the Middle Ages, towards the Renaissance, took place on the sides of the pictorial space.

The patrons of the triptychs for the altars in the churches, those who commissioned the artists to do the work, didn’t dare share the space with the sacred figures on the central panel. They were placed on the sides, but their features were faithfully portrayed. Firstly because the painting tended to be more realistic and secondly because in the “escalation of ostentation” mentioned by Panofsky, being visually recognized functioned as a kind of publicity for the donor.

Another way of introducing some restraint and avoiding any accusations of pride was when they appeared out of proportion, reduced in size in relation to the other figures in the iconography, in order to emphasize their humble condition as sinners before the sacred.

This is the case with the Portinari Triptych, above, commissioned by Tommaso Portinari, a Florentine who worked for the Medici bank in Bruges, Holland. He was represented in the left panel with his two sons and his wife Maria di Francesco Baroncelli, appears in the right panel with their daughter. All in reduced size.

Over time, the frequency with which the donors grow and become more in line with the other characters in the painting increases. There are also cases where they appear in the same space as the main character, but not without permission, they are introduced by some saint who introduces them, who recommends them.

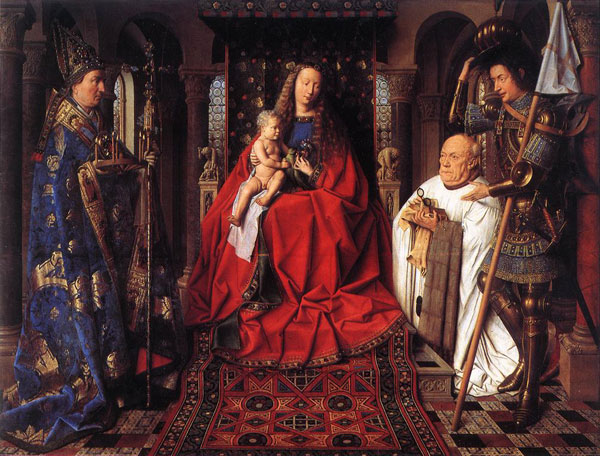

This is the case with the Virgin and Child Jesus (above). Kneeling beside her is Joris van der Paele. He is presented to the Virgin by St. George in armor. The gesture of his left hand leaves no doubt that this is a presentation. Joris was a high official in the ecclesiastical hierarchy. He was in charge of the Pope’s chancellery in Bruges.

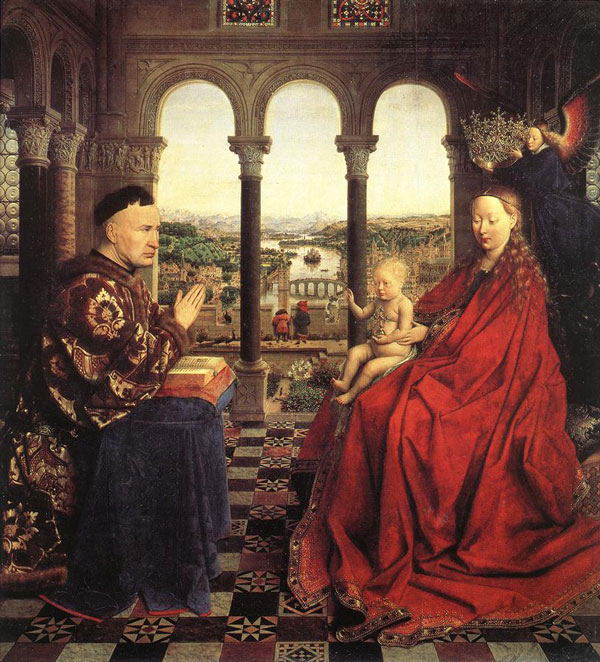

In Jan Van Eyck’s Virgin of Chancellor Rolin (above), from 1435, we have Nicolas Rolin, from a bourgeois family. His role as chancellor gave him important political and economic responsibilities in the duchy of Burgundy. Full-bodied, with a grave look, in luxurious clothes, he appears alone, sharing space with the virgin and being blessed by the baby Jesus. The virgin is without a halo. Instead, she receives a crown from an angel and thus shares with humans the use of the same symbol of power.

In the background, a garden with exotic birds, two figures on the parapet of the building’s gable and a lush landscape that shows that life goes on for the rest of us. The landscape places the imaginary scene of the chancellor’s blessing as a real event, right here on Earth, at a certain time of day somewhere in the duchy of Burgundy.

A few decades ago, a painting like this would have seemed like total nonsense, of limitless inconvenience, a veritable sacrilege, but it was the Renaissance spirit that was already showing what it had come for.

In these portraits of donors in religious scenes, their features were well cared for, as mentioned above. But the situation called for a posture, a protocol in line with the solemnity of the occasion represented. In the isolated portraits, which multiplied exponentially from the end of the 14th century onwards, instead of stiff, expressionless poses, the artist had the freedom to try to bring the subject to life, to tell who they were, not just through their clothes and accessories, but above all by trying to materialize the personality, feelings and emotions of the subject through their features and expressiveness.

It’s common for us to lose the ability to empathize with certain works over time. Just as there are cases of others that were not so praised when they were created, but are rediscovered in later times. There are still countless portraits that have crossed the centuries and we are still able to “talk” to those portrayed. Sometimes there is an inexplicable feeling of closeness and empathy.

This means that we still live with a way of seeing and interpreting these images without a break in continuity with the Renaissance. Even with the invention of photography, to cite something that might seem like a new basis, a break in our production/reading of images, judging by our familiarity with images produced in Europe from the end of the 15th century onwards, we can say that the Renaissance meant the beginning of a chapter that has not yet ended.

Is it because of its realism and objectivity? Because of the non-relativism of reality? This would be a typical argument of Renaissance thinking. It would be like saying that we have reached perfection. It’s too risky to go down this road. History has already shown that we are flexible enough to deny reality its objectivity and turn it into the mysterious manifestation of something incomprehensible. The Middle Ages were exactly that.

Another trap is to imagine that, as a copy of the real thing, the naturalist portrait is determined by the model alone. This would mean expecting that if two painters portray the same model, the portraits will be the same, since the model is only one. This is obviously not the case. Although the two portraits can be considered very faithful, they will follow different strategies and will therefore present very different results.

We can even think of a regionalism in this treatment. Roughly speaking, artists from northern Europe, where Belgium, Holland, Germany and northern France are today, tended to take a more analytical approach. They saw their subjects as a sum of small parts. The Italians, the champions of the Renaissance, on the other hand, had a more synthetic vision and looked more at the whole, at the overall lines and volumes of their compositions.

The portrait above, of an unknown man, illustrates the approach I’m calling analytical. It’s by the Flemish artist Robert Campin or Master de Flemalle. It’s interesting to think about how a painting like this still has a strong relationship with the verbal description of the thing portrayed. Everything that has a name, that has a word associated with it, is distinctively represented in the painting. It seems that Campin took care of every strand of hair, every pore, every beard that showed its tip on the subject’s skin. Every wrinkle and the tiny reflections in the pupil, everything has an individuality and everything stands out from the whole.

The end result is the sum of these details. Robert Campin was an initiator of the Renaissance in Flanders, working for 30 years in the city of Tournay, now Belgium. Rogier van der Weiden and Jackques Darret came out of his Atelier and follow the same approach to meticulous detail in their paintings.

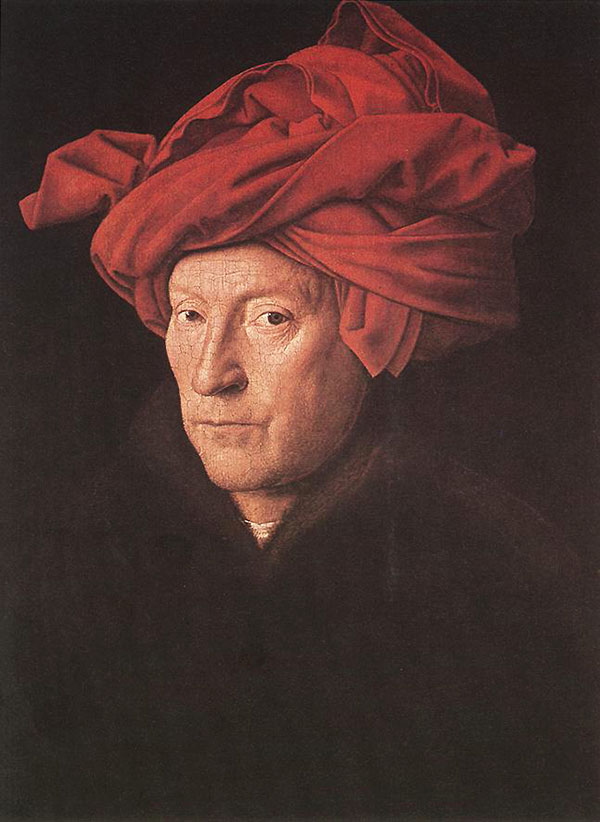

Jan van Eyck was his contemporary. He was another artist who detailed his paintings to the limit of what the naked eye could make out. Below, one of his most acclaimed portraits, “Man with Red Turban”. Supposedly a self-portrait.

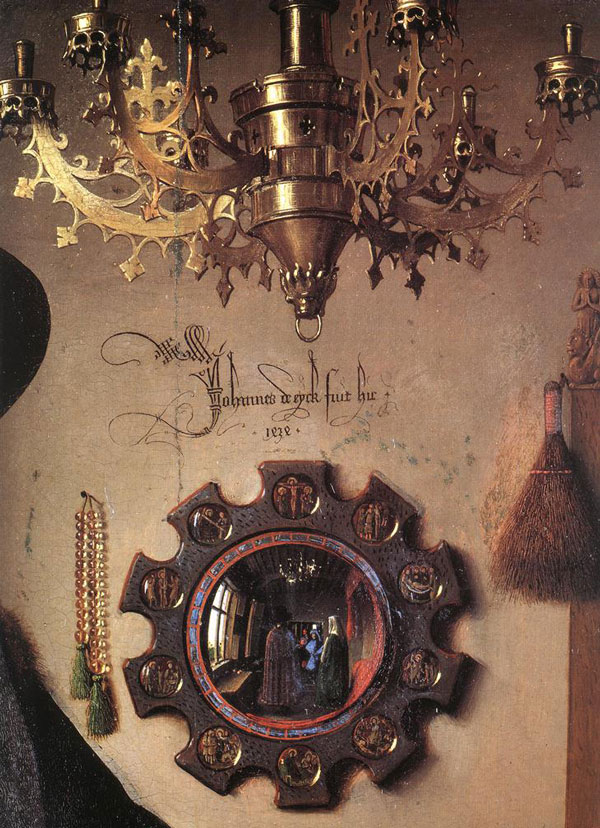

van Eyck’s dedication to detail is also celebrated in his portrait of Giovanne Arnolfini and his wife. Giovanni was an Italian merchant who spent much of his life in Flanders, where he was portrayed by van Eyck.

In this link you can see the rich detail of the Arnolfini portrait in high resolution by zooming in.

Perhaps it’s our perception, which is much more acute when it comes to human features, but it seems to me that this obsession with detail works better with still lifes than with faces. When still lifes with flowers or fruit and food in general arranged on porcelain, crystal and silverware became fashionable in the 17th century, Northern European painters were unbeatable in their mastery of rendering textures, sparkles and transparencies. They already had a long tradition of pursuing the materiality of things.

Meanwhile in Italy, in what I’m calling a more synthetic approach, the concern was more in the direction of lines and volumes, giving primacy to the whole and less to details. This may have been due to the slower adoption of oil painting compared to Northern Europe, as well as a stronger sculptural tradition.

In this portrait of a young woman, Botticelli pays attention to every account of the adornments on her collar and head, but the treatment of her hair, as well as her face, makes it very clear that he was more concerned with drawing than with materiality, and takes on a more graphic character. Perhaps this option has a bias towards the use of tempera on wood. This technique makes it difficult to use overlapping layers of pigment, giving it transparency.

Antonello da Messina – Portrait of a Man (Il Condottiere) 1475

Above is Antonello da Messina with an oil painting. It’s very difficult to say, but despite his great attention to detail, his way of rendering a face is somewhat different from what Flemish painters used to do. One possible explanation could be that, in this portrait, he pays more attention to the modeling of the face as a whole than to the texture or local micro-accidents on his model’s skin.

But perhaps this vivid sensation, which incites us to look more at the whole, to look at the portrait as we would look at a real person in front of us, comes from his ability to give it a very strong expressiveness that takes our attention away from the pictorial matter and directs us to look at the human being, to look into their eyes.

This is very evident in his Annunciation (below). Although it is a painting of the Virgin Mary, it is believed that he used a model. The use of models for religious paintings was very common at the time.

It is part of the iconography of the annunciation that the Virgin is reading when the archangel Gabriel comes to announce that she is expecting God’s son, Jesus. But it is also part of the iconography that both are shown in full body. Messina has innovated and only suggests a presence on the Virgin’s right. He suggests her right hand, which seems to indicate to the archangel that she has noticed his presence but is so fixed in her thoughts that she doesn’t turn her face towards him.

These interpretations or readings of the image are obviously subjective. For me, knowing that it’s an Annunciation, the Virgin’s gaze is completely in tune with the narrative. She feels the weight of knowing what is going to happen, of foreseeing the great suffering that awaits her, but she resigns herself because she knows that this is how it has to be. It’s the look of someone who has the inner strength to accept her fate even though she knows it will be her tragedy. The meticulousness of Italian painting goes in other directions when compared to its counterparts in northern Europe; it is more in this theatricality, this emotionality, than in the realistic accuracy of the details.

So far we’ve looked more at the production of the 15th century. It is common for this period to be referred to as pre-Renaissance, even though all its basic elements are already present. But the point is that right at the turn of the 1500s names like Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo went so far, flew so high, that history consecrated them as the great representatives of the Renaissance in the arts.

Raphael Sanzio (1483 – 1520) must have been someone extremely likeable and affable. The painter and historian Giorgio Vasari (1511 – 1574) refers to him with adjectives such as kind, gracious, modest, gentle and also ponders how it was a blessing of nature to put all this into an extremely talented artist. All this peace of character comes through in Raphael’s work. His compositions are clear, balanced and his drawings are confident and harmonious.

As a portrait painter, Raphael was extremely interested in human nature. He died early, aged only 37, but he enjoyed enormous success and was commissioned for grandiose works, especially in the Vatican. Perhaps that’s why he didn’t leave many portraits.

Above, a drawing he made at the age of 16 at the end of his apprenticeship in Perugino’s studio. The image is extremely vivid despite the inherent limitations of drawing, which doesn’t use color and is constructed with lines that, strictly speaking, don’t exist in nature. It’s a portrait that leads us to reflect that realism in art doesn’t come from the image containing “everything” that the object contains, but rather from knowing how to give the right clues so that the viewer can complete the image in their mind. It is this mental image that induces the feeling that the work is extremely faithful.

Raphael Sanzio -Portrait of Bindo Altoviti 1512-15

Bindo Altoviti was a banker and a lover of the arts. At the time of the portrait he was only 24 years old and Raphael depicts him in an unusual position, with his torso almost on his back, he turns his face towards us, staring deeply into our eyes. There is a lot of sensuality in the image as a whole, due to the shape of his very young face, the position of his hand, which seems to be holding his cloak so that it doesn’t fall off, and the hair on his skin, which makes us imagine the softness of his touch.

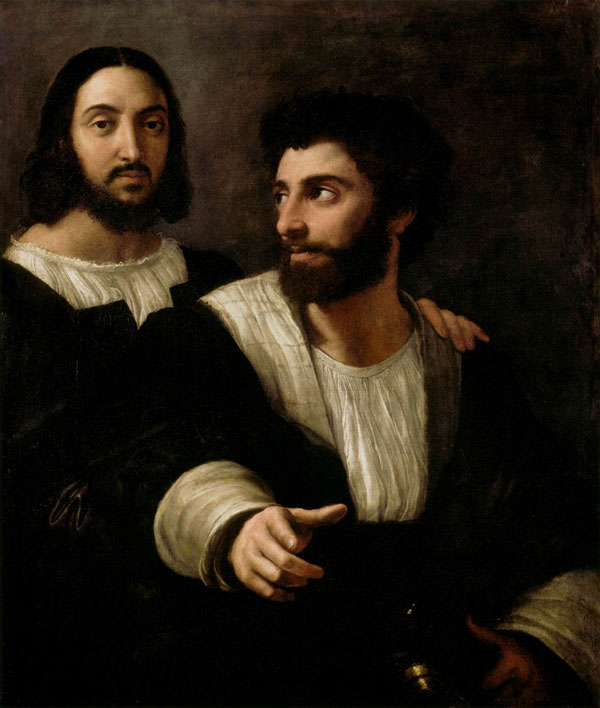

Raphael Sanzio – Self-Portrait with a Friend” (1518-1520)

Raphael Sanzio – Self-Portrait with a Friend” (1518-1520)

More experiments by Raphael. This double portrait with a friend, believed to be his pupil Giulio Romano, has the curious look of a snapshot. The friend’s gesture, as if asking Raphael, and the friend staring at us, give the appearance of an image captured like a photograph.

Another surprising portrait of Raphael. Pope Julius II is known as the “warrior pope” because of his aggressiveness in commanding troops in battles to consolidate temporal power over pontifical states. His papal name, Julius, was chosen because of his admiration for Julius Caesar, the Roman general. However, Raphael chose to depict him with a sad, introspective air that seems tired. Far from a heroic portrait of a general and equally far from a pious portrait that would suit a religious leader, it seems that Raphael decided to represent the man behind the character.

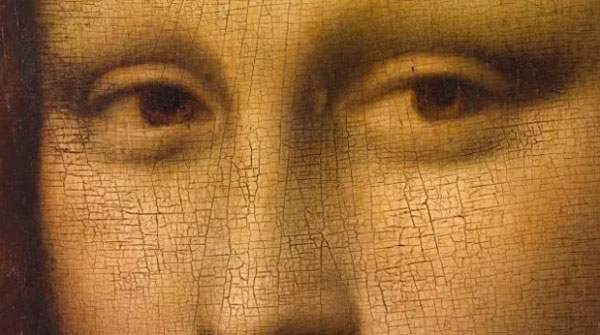

To close with what is certainly the most famous experiment in portraiture in Renaissance painting, we have Leonardo da Vinci’s Monalisa or Gioconda. There are many wonderful and more or less contemporary portraits of the Gioconda. There is no solid basis for arguing that this one is far superior to many others. Much of its fame today comes from the fact that it was stolen in 1911 and recovered in 1914. This episode gave it a lot of publicity at the time. Since then, volumes and volumes of theses and analyses have been written, ranging from the most serious to the most outlandish theories. Countless studies have been carried out with scientific apparatus and what has been found is that the painting has already been significantly altered over the course of its more than 5 centuries.

But it’s also true that it caused a great deal of admiration among those who saw it in its day. What is certain is that there was a current opinion that painting should be faithful to reality. We can say that from north to south this was the understanding of the role of art. The first attempts in this direction sought to observe the model very closely, as if with a magnifying glass, in order to reproduce all its details and minutiae. This is especially true of the Flemish painters, Jan van Eyck being perhaps the best representative of this approach.

But as we get closer to the 1500s, we often find another approach, which would be to observe the subject from the viewer’s point of view, at a certain distance, and thus bypass this almost microscopic world and represent a human presence captured live.

Gioconda is, among other virtues, an extremely happy case of applying this principle. The fact that Leonardo achieved a very vivid impression, a very real presence, without using details that he decided to relegate to the superfluous, must have caused a great deal of astonishment and raised many questions.

His painting is neither schematic, ornamental, calligraphic as was done in the Middle Ages, nor an attempt to highlight every hair as was done at the end of the 15th century in Flanders. To use a parallel with photography, it would be something like using a soft-focus filter. This is what Leonardo called sfumatto.

The basis for this technique working is the fact that in our reading of images we don’t actually process every detail of what our eyes can capture. Vision is a game of approximation between what our eyes see and what we know from previous experiences. Sfumatto plays on our ability and tendency to complete what is missing from the image. An incomplete image left to our interpretation can work better, in terms of realism, than an image full of details that contradict what would be a genuine visual impression.

XI. The good and the beautiful

Where to look for beauty? This was the great question that at the end of the 15th century motivated the emergence of various theories of art. Since antiquity, there had been no philosophical discussion trying to understand art from the point of view of its nature, objectives and methods. It was tacitly accepted that a work of art should be beautiful and inspire virtue. There was not yet, for example, an art made to shock the public, as would later be the case. This condition of bearing beauty, together with the new premise that images should take nature as their model, led to the question of where this sought-after beauty would come from. Was it tangible reality? Did the artist have to go in search of perfect models to copy? Or would it come from within the artist himself, whose hands would be guided by a profound notion of what a beautiful body or face would be? If it came from within the artist, how did he acquire this knowledge? Observation? Divine revelation?

In any case, beauty at that time didn’t have the connotation it has today of just something that pleases the eye, and even less of something purely conventional and perversely capable of being used as an instrument of domination within the concept of soft-power. Beauty was not a colonialist weapon or a pretext for inflicting frustration on citizens, leading them into a spiral of consumerism.

Beauty had an intimate relationship with the sphere of the divine. It was the perfect manifestation of creation. It was the channel, the sign, the evidence through which God made himself present in our earthly world. Even with all the disenchantment in today’s world, the idea that a baby, a flower or the multicolored patterns in marine formations are something so beautiful that they can only be the fruit of an intelligent creation still seems to resonate well.

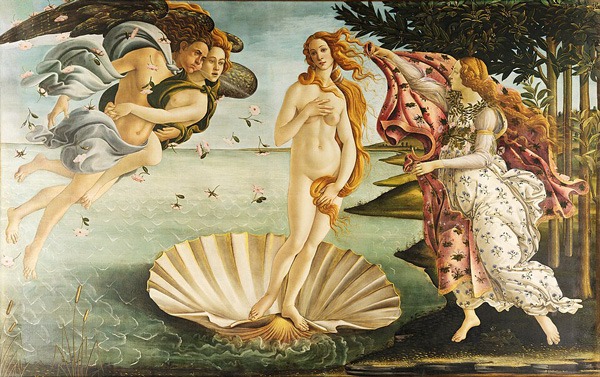

For Leon Batista Alberti, who wrote the highly influential and aforementioned treatise De la Pictura, beauty came from observing a principle of harmony between the parts and between the parts and the whole. This is a rather vague notion and has its origins in the thinking of ancient Greece. It is one of those definitions that need examples and, in fact, it is the examples that create the notion, that give meaning to the definition, without actually going through the analytical rigor that a definition would require. For the Renaissance, the examples came from Classical Antiquity. The Greek and later Roman gods were presented in art as human forms. For Christianity, despite its condemnation of the body, the human being was the creator’s favorite creature. These two notions came together so that beauty in the Renaissance was largely represented through the human figure.

But the important thing to note here is that it is a notion of beauty that has the character of a formal predicate, limited to appearance. It is present when certain visual characteristics are respected. It can be found in nature, in ancient works of art and it can be produced by the hand of the artist. In any case, as long as the object under consideration presents this condition of harmony of forms, beauty is there.

Still with Alberti, with this phenomenological understanding of beauty, came the idea that since it was very difficult to find perfect beauty, a Venus or an Apollo in the flesh, it was up to the artist to start with tangible nature, which was right at his disposal, and use his talent to surpass it in art, altering what he felt should be altered. The artist is the one who observes the real world and remakes it into art, correcting and improving it. This was a kind of naturalistic and at the same time idealistic formula for art.

However, there was also another totally different point of view, derived from the aforementioned philosopher Plotinus (205 – 270). Plotinus is known for having drawn heavily on the philosophy of Plato (427/8 – 347/8), but in a more mystical way. His philosophy, baptized in the 19th century as Neoplatonism, was extremely influential in Christian theology throughout the Middle Ages and had a considerable survival in the Renaissance.

Pairing well with the duality of body and soul, which is at the basis of Christianity, Plotinus considered that beyond the tangible world there is another that is abstract and immaterial. The material world is illusory, perceived only by the senses, it is a derivative of the parallel world which would actually be what we should call real. This spiritual world is the perfect world, where everything is perfect, everything is good and everything is beautiful.

Plotinus’ Neoplatonism was applied by the Italian Marsilio T. Ficino (1433 – 1499) in a theory of art. According to Ficino, a beautiful body is one in which its material version best corresponds to its ideal form, which inhabits the world of perfect ideas in the parallel world. Earthly beauty “represents the triumph of God over matter” (quoted by Irwin Panofsky in Idea). These are already characteristics that go beyond the question of appearance and link beauty and intangible spheres in an ideal, perfect, divine world.

That’s where the idea that beautiful people are good and that good people will certainly be beautiful came from. That’s where the condemnation of ugliness in its many variants came from as something bad, not just ugly. Today, we seem to be trying, by a very laudable moral decision, to eliminate this duality of beautiful/ugly correlated with good/bad, but the influence of Platonic thinking is still strong.

Returning to Ficino, the most interesting thing comes when he says that God has imprinted in all of us, in our souls, the knowledge of the beautiful and ideal and this is how we recognize when something, a work of art, is beautiful. The artist is someone capable of searching deep within for these perfect forms and bringing them into our world as works of art.

With Alberti, then, we have a more formal, more earthy, more Aristotelian vision. He developed the concept of harmony of forms in advice on the arrangement of elements in pictorial space, the use of color, observation of nature as the ultimate reference and also the use of linear perspective as a method. On the other side we have Marsilio Ficino with a metaphysical view of beauty that still inextricably linked it to the concept of the good. Beauty, as a metaphysical entity, takes on a character that is even independent of the world of things, the visual world or the senses, a character of absolute perfection that, when incarnated in a work of art, translates into formal beauty as we know it.

That was the discussion. Among the artists, in their work as a whole and also in their reflections, when they left some writings or when their opinions were recorded by friends and biographers, we more often find a selective use mixing one vision and another.

Observation of nature was fundamental in breaking down subject and object in art. Moving away from the Middle Ages, the artist recognizes the autonomy of the outside world as his object and assumes his autonomy as the subject who creates a version, using techniques that he learns and develops. He repudiates the concept of a simple copy and adopts the stance of “remaking better”, of surpassing nature by making it more beautiful or truly beautiful.

From the mystical vision of Neoplatonism he borrows the justification that authorizes him to dare to surpass creation, to make of himself a demiurge, because he already has within him, as a gift, knowledge beyond experience, knowledge of the ideal world.

Marsilio Ficino’s metaphysics also supports the concept of genius, so dear to artists like Leonardo da Vinci, although the latter in particular was more in the tradition of Alberti. The idea that beauty, a gift from God, lives within us, but only the artist has the ability to go deep into his soul and heroically bring it to the surface, is undoubtedly very seductive for those who sought self-affirmation, for those who sought to break away from the nickname of mere craftsman and have their craft listed among the Liberal Arts.

Raphael’s female figures are the very embodiment of ideal beauty as it was understood in his time. One of his letters in which he comments on his method is very famous. The letter was addressed to his friend Baldassare Castiglione in response to the latter’s praise of his Galatea (above) in the fresco that Raphael executed for a banker of the Pope. The letter, quoted in “Ideal and Type in Italian Renaissance Painting”, an essay by Enst Gombrich, reads as follows: