The history of the Lerebours et Secretan brand is so interesting that before we go into the specific question of this lens, let us dwell a little on the parcours of its founders. We can thus better understand the profound transformations that Europe underwent in the nineteenth century. We can draw considerations about cultural changes organically linked to the advent of photography when we look at it from a more anthropological perspective. Photography was one of the fields in which a very important change of values, brought in the midst of the bourgeois revolution, was clearly manifested.

The history of the Lerebours

Jean-Noel Lerebours arrived in Paris with his family from Normandy at the age of 12 in the year 1773. Jean-Noel had four brothers and his father was a chapelier, he made hats. Soon after arriving in the capital he entered as an apprentice in a workshop dedicated to the manufacture of eyeglasses. At that time, this industry was growing very rapidly driven by the dissemination of the press, books, periodicals and knowledge valorization – in an article about a Petzval type lens from Derogy, I gathered some interesting information about the manufacture of lenses at that time, link: Rapide nº4 Derogy.

Jean-Noel quickly switches to an optics workshop, from a certain Louvel, where he stayed until he was 18 years old. At that time, his father died and he, as the new head of the family and responsible for his mother and younger brothers, begins an enterprising career. He acquired lens polishing utensils and start accepting orders that arrive, from the best opticians and in exciting quantities. The business is going well, Jean-Noel lives austerely and works hard. There is a great demand for telescopes, both astronomical and terrestrial, and the firm Lerebours is establishing its name and growing among the French manufacturers. The competition was strong and the best reputation of English instruments forced a much lower price for local manufacturers.

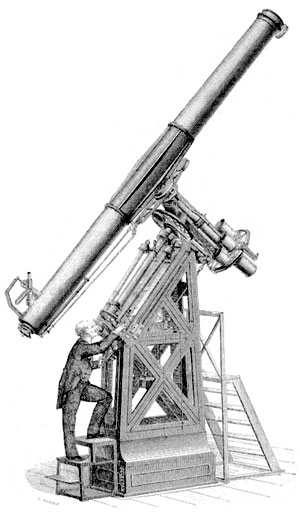

The telescope (on the left) gives a dimension of the degree of specialty and technical capacity that the Lerebours firm reached in its maturity. Made in 1823 it had a lens of 24 cm in diameter and a focal length of 323 cm. The diameter of the lens is a kind of attestation of competence for the manufacturer of telescopes. A 24 cm lens is an imposing landmark even today. This telescope was immediately acquired by the Paris Observatory. Jean-Noel met many honors with numerous awards, medals and titles such as Opticien du Premier Consul, then emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte. Later he was Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur, Louis XVIII.

The telescope (on the left) gives a dimension of the degree of specialty and technical capacity that the Lerebours firm reached in its maturity. Made in 1823 it had a lens of 24 cm in diameter and a focal length of 323 cm. The diameter of the lens is a kind of attestation of competence for the manufacturer of telescopes. A 24 cm lens is an imposing landmark even today. This telescope was immediately acquired by the Paris Observatory. Jean-Noel met many honors with numerous awards, medals and titles such as Opticien du Premier Consul, then emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte. Later he was Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur, Louis XVIII.

There was full awareness of governments that technology would be decisive in the power and competitiveness of nations. When Jean-Noel started with his first lunettes, he used English flint glasses, but in the course of the developments, in collaboration with other members of the local industry, he started to use French glasses and obtained parity in quality with the British manufacturers. To stimulate rapid development and its positive implications for the national economy, there was a network of information exchange, collaborations, awards and dissemination of technological achievements. Institutions such as the Academy of Sciences, the Society for the Encouragement of the National Industry and the Universal Exhibitions fulfilled this role of fostering a greedy environment to absorb new technologies. The manufacturers were eager for medals to endorse the quality of their production and cash prizes were offered to anyone who presented solutions to the most pressing problems of the day, both in basic science and industry. This was new and totally different from craft production and feudal organization in guilds and industry associations whose purpose was to always do as it had always been done. It was only at this time that a collaboration between university and industry was born, between scientists and businessmen, valuing the different ways of doing, productivity, the new one replacing the traditional one – in Petzval lens article, the development of his optics for portraits is analyzed under this angle of how science finally met technology – link: The Petzval Portrait Lens.

Jean-Noel Lerebours was widowed and married to a seamstress who was the mother of Noël-Marie Paymal, the son of an unknown father. The boy soon becomes interested in business and joins the firm that was already a large company in its field. In 1836, Jean-Noel officially married and became Noël-Marie Paymal, now also Lerebours, his heir. With the death of the adoptive father in 1840, it will continue and expand the firm’s business on a much larger scale, as with the invention of photography the optical industry has experienced a hitherto unimaginable growth.

The importance and prestige of the optical and photographic industry, in the figure of two of its leading brands, can be evaluated considering that Lerebours and Chevalier (another renowned optician and manufacturer) had their businesses in one of the noblest points of Paris , on the Place du Pont Neuf. In the building on the left, photo above, Lerebours’ shop and studio, on the right was the maison Chevalier. Below is the current view of the buildings.

Noël-Marie Paymal Lerebours was a key figure in the development of photography. He not only manufactured lenses, cameras and field, studio and laboratory accessories, but was himself a great daguerreotypist, editor and influencer in all developments, dissemination and uses of the new invention.

Soon after the announcement of the daguerreotype, in 1839, when the process was bought by the French government and released into the public domain, Daguerre and Isidore Niépce signed a contract with Alphonse Giroux, merchant and manufacturer of fine woodworking, to produce the only cameras authorized to carry the seal / name of Daguerre. But immediately, Noël Paymal Lerebours, who was not lacking in prestige as an optician and manufacturer of scientific instruments, also began to manufacture cameras and all the apparatus necessary for the production of daguerreotypes.

Like Giroux, he also publishes a booklet entitled “Historique et description des procédés du daguerretitie et du diorama – Rédigés par Daguerre et ornés du portrait de l’auter“. To the official text of Daguerre, presented in the proceedings at the Academy of Sciences and which earned him a good pension for life, Lerebours adds his notes and observations on the process. The publication is a great success and had several subsequent editions.

An initiative that still guarantees a special place in these first years of photography was the publication of Excursions daguerriennes, with the pompous subtitle Vues et Monuments les plus remarquables du Globe. There were two books (1841 and 1843) with engravings made from daguerreotypes of collaborators and from Lerebours itself. Views of France, Egypt, Italy, Russia, Algeria and even the Niagara Falls are reproduced through engravings made from daguerreotypes. The process of transferring the picture to the engraving was partly mechanical, using the daguerreotype metal plate itself, and partly manual. It is certain that, in observing the images, the engraver made a good contribution from what he knew of the techniques of drawing and composition.

In the scene below, taken from Excursions Daguerriennes, shows the castle of Fontainebleau. We can be sure that a Daguerreotype would not be able to reproduce running horses. But these elements added a posteriori gave balance and life to the scene. Also the clouds, so difficult to reproduce in a process that is sensitive only to blue and ultraviolet, were probably an addition of the artist.

But these details probably did not bother about the realism or authenticity of the scenes depicted. At a time, when even short trips were difficult or impossible for the majority of the population, to see “photographs” of Roman ruins, churches in Moscow and mosques in the Maghreb, it must have been magical in itself.

As no one had seen what photography was, since it did not exist, what these pioneers did, soon assumed the identity of the new medium. They became canonical and determined for the next decades what would be the photographic. What subjects, what points of view, what perspectives, how to arrange foreground, how to organize the scale of things, all these aesthetic questions were being established and to a large extent were not new but borrowed from painting and the arts. A certain autonomization of photography would only come in the twentieth century.

Lerebours and collaborators were very active in establishing these canons. In 1841, less than two years after the announcement of photography, Lerebours publishes with Marc Antoine Gaudin a Photography Treatise where he again presents the daguerreotype process, with some modifications, and also discusses the portrait, the choice of background, poses and clothing, landscape, still life and other issues that formed the understanding of what and how photography should be. In that year of 1841 Lerebours reported having made more than 1500 daguerreotypes. His production would soon reach the same amount of portraits in just two months. The number 13 on Place du Pont Neuf, became the place where Parisian photographers met to discuss, share and compare their results in photography.

The photo above shows, further to the left, Noël-Marie Paymal Lerebours. Standing up is the German Friederich von Martens who worked for Lerebours and developed a panoramic swing lens camera – more information about this type of camera at this link. On the right is Marc Antoine Gaudin. The other two, seated, are unknown and probably workers of the firm Lerebours.

In 1845 Noël-Marie associates with Marc Secrétan, mathematician and astronomer. They change the name of the firm to Lerebours et Secrétan. Lerebours is dedicated more to the photographic sector and Secrétan will develop the firm’s vocation of origin in the manufacture of telescopes and scientific optical instruments. The union is very fruitful and gives a new impetus in the company. Secrétan, Swiss and just arrived in Paris, soon finds its space and creates a reputation among the leading scientists of the time. The association runs until 1855 when Lerebours retires leaving a company of international fame and high market value. Secrétan then gives the production of lenses a more scientific and less empirical character. It introduces more calculation and math as the basis of the drawings and developments. Already in the hands of other heirs the firm remains, but will leave the Place du Pont Neuf in the 70’s and will not know other glorious times like those of Lerebours. The brand will be active until the 1950s.

The Lerebours and the new order

What is interesting in this story, apart from its novelistic aspects, is to consider the change in the way of life that was brought about by the Bourgeois Revolution and the whole ideology of the Enlightenment. The key point is the prominent place that they agreed to scientific knowledge. The impact of these transformations was enormous in the whole dynamics of society. For centuries and centuries the chance that someone born in a humble family had to achieve a leadership position was basically through weapons. All the European nobility that formed from the end of the Roman Empire was militaristic. If someone was a plebeian, but very good at killing his fellow men and leading wars and looting, he would eventually become a general, a king or even a great emperor. The ecclesiastical way, another option for power, was soon occupied by the good families, and only a charismatic preacher and very politically capable could, from humble beginnings, achieve notoriety in the hierarchy of the Roman church. There was still trade, the very cradle of the bourgeoisie, but to be a merchant or banker, even with great success, did not make one a properly respected and honored person. They were seen, at most, as a necessary evil and could not, no matter how much they could donated to church building and financing wars, have their way of life elevated to the condition role models, like nobles and the saints usually were.

What Enlightenment, as part of the modernity package, was able to provide was a positive conceptual basis for manufacturing, labor, and the transformation of nature into goods and wealth that these activities never had. Looting, seizing, collecting taxes, and all coercive forms of enrichment, have always been considered far more noble than working. What gave the manufacture this veneer of honoured activity and something far removed from the traditional manual and repetitive work, was inventiveness, intellect, study, scientific knowledge at the service of Nature domination and the production of goods. To the old typology of the models of our Western culture, basically composed by the warrior, the religious and the artist, was added the coupled scientist and his fellow entrepreneur, the new creators of wealth.

Photography is really exemplary as part of this transformation. In optics and chemistry, the gradual insertion of scientific and industrial approaches into an activity that had previously been a craft, is very evident. The notoriety conquered by the Lerebours, father and son, the route they took, beginning with the simple polishing of spectacle lenses, and later being active in circles of astronomy, installed in the nicest spot of Paris, and yet “knight of the king’s legion of honor”, that is a classic case of this transition to a new status of manufacturing when mixed up with science and technology. The understanding of this transition by Lerebours son is attested by his association with the mathematician Secrétan. The success of Petzval’s lens, another mathematician, was a defeat of methods of intuition or sheer trial and error, which was formerly the modus operandi of great opticians like Charles Chevalier and Jean-Marie Lerebours. Even Niepce, Daguerre, Talbot and Florence, can not be considered much more than dilettantes. Their merits are more in having been visionary and very stubborn. But soon the photographic processes became subject of names like John Herschel, and its processes happened to be seen like part of a body of knowledge that was developed in basic research in chemistry and later applied cascading to technological processes.

Stories like that of the Lerebours add up to thousands of others in which work and study have won not only financial comfort, as the upper bourgeoisie always had, but also respect and admiration of society, as the upper bourgeoisie had never had. It was like a new path of social ascension that was open to all through hard work and study. The nineteenth century experienced many misfortunes and social commotions, but there was also a climate of euphoria and confidence in the future that we can’t find today.

This lens

In his catalog of 1846, therefore soon after the entrance of Secrétan in the business, two types of photographic lenses are mentioned: Objectif Achromatique and Objectif à Verres Combinés (verre is glass in French). They appear organized by the size of the plate to which they are intended. It was still not common to speak of focal length and nor diaphragm or aperture to specify a lens. Whole plate was 16 x 22 cm, and then came its fractions 1/2 plate, 1/4 and 1/6. Later the somewhat larger size 18 x 24 cm was adopted as the European whole plate size and this is a format that is sold to this day.

Objectif à Verres Combinés was another name for Petzval’s portrait lens and had two achromatic doublets, one cemented on the front and one air spaced on the rear, leaving the diaphragm positioned between the two sets. It was also known as double objective or “German system”. For details and history of this lens, visit the The Petzval portrait lens page.

This objective sample, from Lerebours et Secrétan, is a lens of the Objectif Achromatique type, or objectif simple, objective for landscapes (paysage), or objectif pour vues, that would be objective for “sights”, a term probably coined by Niépce, who used it in his writings . All this meant that it was a lens for static subjects such as landscapes or architecture because the aperture needed to give sharpness across the field was very small and therefore the exposure times too long for the processes of the time.

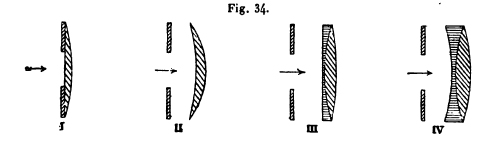

In the diagram above, taken from Etiene Wallon’s 1891 optics treatise, this landscape lens corresponds to scheme IV. It features a biconcave flint glass cemented to a biconvex crown. Schemes I and II were typical of camera obscura and III was used in the first daguerreotype cameras. By having this type of construction and by the serial number, engraved just above the name, No. 7456, this lens must have been manufactured around 1855.

In the diagram above, taken from Etiene Wallon’s 1891 optics treatise, this landscape lens corresponds to scheme IV. It features a biconcave flint glass cemented to a biconvex crown. Schemes I and II were typical of camera obscura and III was used in the first daguerreotype cameras. By having this type of construction and by the serial number, engraved just above the name, No. 7456, this lens must have been manufactured around 1855.

A curiosity about Lerebours et Secretan lenses is that in addition to engraving the serial number on the brass barrel, the manufacturer took the care of marking it also on the lens itself, as seen in the photo below.

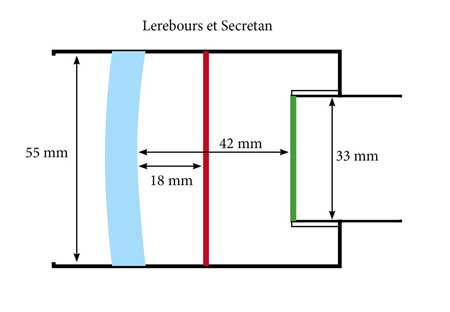

The basic dimensions of this lens are shown in the diagram below. It has two particularities. The first is that the doublet is like in a recess into the lens tube. I wondered, why would anyone do that? This part inside the camera! My hypothesis is that the intended effect was to give more room to slide the lens forward through the rack by stretching tube without moving the lens in relation to the diaphragm. I imagine it has been designed for a camera with less mobility for focusing leaving all movements to the rack. The 33 mm trip allows one to focus from infinity to a distance of only 2.2 m, probably more than enough for a lens like this. This would allow one to use it on a camera even without bellows or “drawer” system. Maybe it was designed for a fixed camera, a simple box.

The other particularity, which is harder to explain, is that on top of the regular front tube where washer diaphragms are installed, this lens also a slit for Waterhouse type stops at 18 mm from the lens. I believe this must have been a later adaptation of some creative former owner. It must not be original from factory.

The other particularity, which is harder to explain, is that on top of the regular front tube where washer diaphragms are installed, this lens also a slit for Waterhouse type stops at 18 mm from the lens. I believe this must have been a later adaptation of some creative former owner. It must not be original from factory.

But at least the work was done with great zeal and looks even original. Both the cuts and the insert to support diaphragms are very well made. But I have found nothing in the existing literature to corroborate this kind of duplicity of diaphragms.

In this type of lens, the diaphragm is selected by inserting a washer into the tube in front of the lens. A metal piece (on the right), which fits tight into the same tube, holds the diaphragm securely in place. The cap, shown in the first photo of this article, was usually used as a shutter because times were very long. Used without any diaphragm the aperture of this lens is f / 7.7. But this should be a situation just to focus on a slightly brighter image. Apertures in practice should be f/16 or smaller.

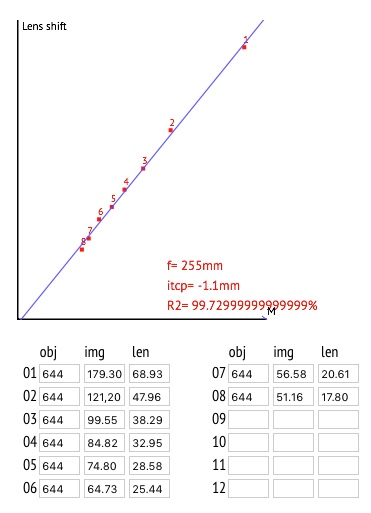

The focal length was evaluated by successive measurements of magnification that were plotted in the chart above (see calculator in this link) and the result was 255 mm. This is consistent with the lens diameter having 55mm because at that time they used to have a diameter of 1/5 of the focal length, according to Wallon and also Monckhoven. As for the position of the diaphragm in relation to the lens, a matter that was much debated at the time, it is known that the standard 1/5 of the focal length was adopted by most manufacturers for this type of lens. In the above diagram is marked 42 mm, that was measured to the surface of the lens. This should correspond approximately to 50 mm, at some point inside or near the doublet, and would then give us 1/5 of the focal length.

Using this lens

The photo to illustrate the use of this lens was made at the Jardim Botânico de São Paulo. It was mounted on a Thornton Pickard Royal Ruby whole plate camera: 18 x 24 cm. Instead of film, I took advantage of the fact that I’m testing home-made dry plates with silver gelatin, and it was then a 2-mm glass emulsified with the basic recipe of Joseph Maria Eder in his 1883 book.

This was the third batch of emulsion I prepared and the result was already quite satisfactory, keeping the natural limitations of the formula. On the left the appearance of the plate after it was developed. To take the photo I used a set of cut diaphragms for this lens as I don’t have the originals. The aperture chosen was f / 45 and the exposure time was 3 minutes on a day partly cloudy but very bright. The photometry for ISO 3 gave 30s at f / 45½ with an EV = 6.6. I deliberated increased exposure as the scene was basically green ant the emultsion is not sentitive to that color. The develpment was 12 min in Parodinal 1:20 at 20 ° C. It is possible to notice a vignette at the corners of the plate. I did not find this lens in the Lerebours et Secretan catalogs I could find, so I do not know what the official format recommendation would be. I think it would be half a plate because its circle of image is 25 cm and to be whole plate of the time (16 x 22 cm) would have to be at least 27.2. Being a lens for architecture and landscapes, one should have some freedom of movement.

I still can not get rid of flaws and stains on the dry plate. The image below is a direct scan of the negative but has been cropped and retouched to eliminate blemishes in the emulsion and spots from the development.

The result surprised me. We see in museums images made at the time and they are indeed very good. But this image is different from the historical samples because while the lens is old, the medium is fresh. I felt that the vintage photographs because they had already undergone a degradation of the material itself do not give a precise idea of what they must have looked like to those who saw them in their own time. I imagine that experiences like this can inform us a little more about the quality of the optics without the time influence on the printing itself. Of course, with f / 45 any lens has an obligation to look good, but even so, to think that already in 1855 had access to an image with that quality is something that always surprises, accustomed that we are thinking that everything must have greatly improved after such a long period of time.

More detailed views of the same scan:

To finish, just as curiosity, a scan of a print by contact, on paper Ilford fiber, the entire plate and without croppings and retouchings. I looking forward to improve the emulsion in the next batches.

Bibliographic note: Most of the information on the history of Lerebours et Secrétan has been consulted in the publication of Patrice-Hervé Pont and Jean-Loup Princelle, available for sale on the publisher’s website: Le Reve Editions. I used also the book on French lenses from C. D’Agostini.

Comment with one click:

Was this article useful for you? [ratings]

Wonderful article, enjoyed reading this very much … I have a few similar lenses and we seem to enjoy the same books !

Cheers !

Rudi A. Blondia

A most interesting and informative post with lots of factual data. Great photos! I have one L&S lens, probably a Petzval whole plate. Almost no depth of field when shot wide open, low contrast but sharp.

Hello. I am researching a photographic project of 1853. Gustave Le Gray apparently mainly used the Lerebours and Secretan lenses, according to his written pamphlets. This project entailed photographing murals in situ in the Galerie des Fetes in the Hotel de Ville, Paris. These murals, approx. 6 foot tall, were approximately 30 to 35 feet from the floor of the hall. The final photographs taken of the murals were large: approx. 14 x18 inches. Were there lenses at that time long enough to have allowed Le Gray to take photographs of the murals from the floor level? They would be very long lenses, I would assume. It’s also possible that he photographed from ladders or scaffolds…..Thanks for any help in this research….If you would like to see the photos please go to YouTube and search for “Lost Murals Le Gray” and you will probably find a video presentation…..

Hello, one important information is missing there. In order to simulate which lenses would be suitable for such project, it is important to know how far from the murals could the camera be positioned. Long lenses were never a big problem. The short ones, capable to embrace a wide angle, these are the tricky ones. In architecture, the wide angle lens is quite often requested as the photographer normally find a obstacle, like the other side of the street, and can’t get far enough to use a regular lens. If you can provide me the available distance from subject to camera, I believe I can calculate what sort of lens would fit better.

There is an extensive list of surviving L & S (both landscape and portrait Petzvals) lenses on page 6 of this LargeFormatPhotographyForum article.

https://www.largeformatphotography.info/forum/showthread.php?63733-Lerebours-Serial-Number-Rice-Writing

I have just added your traditional Landscape lens to the list!

What a fine, balanced and informative article this is!