Photography in the 1920s

In this room, the idea is to examine the main ways in which photographers could relate to their activity, what they were looking for and how they understood themselves, in the period leading up to the launch of Leica. It will serve as a complement to the previous room where the focus was on the supply of cameras in the same period. Together, the two visions should make up a scenario that helps to understand how and why Leitz’s small camera sparked a revolution in image production.

Everyone can photograph

In the first 50 years of photography, although it was a huge and undeniable success, it was more in the sense that everyone knew what it was and that almost everyone could get themselves photographed. There were itinerant photographers making tiny ferrotypes for a very affordable price and there were luxury studios making life-size carbon or platinum prints. Between the two extremes, millions of Cartes de Visite.

With the invention of dry plates and later roll film, both using gelatine-based emulsion, which together with general-purpose lenses such as the Rapid Rectilinear, made it possible hand held photography, without a tripod or black cloth, almost anyone could become a photographer.

It was the boom in box cameras and also the external photo-finishing services. The amateur photographer no longer needed to deal with chemicals and complicated processes. In short, photography became more democratic.

Two types of amateurs

Professionals obviously didn’t go for these box cameras or their equivalents. They didn’t offer features and quality compatible with their needs. What’s more, “handheld” photography went against a whole image formed over decades about the act of photography. The consumers of this new instant photography and the situations they photographed did not clash with the work of professionals. It suited everyone that the territories remained well separated. On the one hand, serious photography for special occasions and, on the other, leisure photography, the fun of places, friends and family in informal pictures in which quality was not at the top priority.

Those who felt most uncomfortable with the avalanche of new colleagues were the older amateurs who practiced technically elaborate photography. They used professional equipment, processed their own photos and considered themselves more than photographers: artist photographers.

The term amateur in English or French, related to some activity, comes from the Latin amator, and literally means one who loves. But the term has undergone a transformation since its origins. In the beginning, it meant someone who, precisely because he loves, studies and knows a lot about the object of his passion, photography in this case. That’s why being an amateur photographer would denote dedication and knowledge of photographic equipment and processes. But at the beginning of the 20th century, this meaning was joined by another such as the simple opposite of professional, which could mean someone who doesn’t master the subject, who doesn’t know it except very superficially. Amateurism, for example, is a term used specifically to denote a lack of skill or knowledge.

Today it seems that superficiality is what has remained. If we want to mean a non-professional who is at the same time a profound connoisseur, we have to add something to the term amateur. In his book Vernaculaires, essais d’histoire de la photographie, Clément Cheroux suggests a distinction. He talks about amateur expert and amateur usager, which would be amateur expert and user. It has the sense that the first is the one who is really knowledgeable and the other is simply a user.

None other than Alfred Stieglitz, in an article published in November 1899 in Scribner’s Magazine, was concerned about the growing deterioration of the term “amateur”. It’s worth a long quote: “Let me call attention to one of the most universally popular mistakes in photography: classifying supposedly excellent work as professional and using the term amateur to convey the idea of immature productions and justify terribly bad photographs. In fact, almost all the best work is, and always has been, done by those who pursue photography for love and not just for financial reasons.” (op.cit. Photography: Essays & Images)

The title of the article, Pictorial Photography, refers to a current in which Stieglitz was, at the time, an illustrious representative. He, among many others, sought to give the status of art to photographic images, in contrast to the mechanical process that had always been the very identity of photography, Talbot’s“Pencil of Nature“, the pencil of nature in contrast to the artist’s pencil. In this direction, many photographers produced images with pictorial themes, fuzzy outlines, evanescent figures and indistinct backgrounds, because these were resources enshrined in painting, the canonical form of art.

Still in the trenches of the serious amateurs, there was another group who, in order to differentiate themselves from the uncompromising amateurs, advocated photography that was very faithful to the visual impression. It was a photograph that only the best optics and large format cameras could provide. No chance for popular box cameras.

There was even a heated debate among the most dedicated amateurs as to whether photography should always be perfectly sharp in all its parts or whether soft images, as we call it today, was a permissible resource in photographic production. We can better understand Stieglitz’s position in his article Pictorial Photography, his concern and even revolt in defense of a certain type of amateur photographer, if we consider that the defenders of sharpness maliciously labeled the images of pictorialists as flawed, lost photos and the result of bad amateurism. The label fit perfectly because at that very moment an army of amateur users (to use Cheroux’s term) were producing millions of photos with cheap lenses, shaky and poorly focused, using box or vest pocket cameras.

Some of the expert amateurs, who had played a leading role in photography from the outset and who had always been at the cutting edge of optics, chemistry and mechanics, saw the sharpness of images as a parameter to differentiate themselves from the new photographers and their shaky and/or out-of-focus photos. In her book Le flou et la photographie, Pauline Martin says “In this context, it is a question of delimiting a know-how and, with the emergence of photography clubs all over France, the term flou increasingly immediately designates a basic defect to be corrected, namely a lack of sharpness. The poor quality of the focus and of certain lenses results in what La Photographie – a popular magazine not intended for a specialized audience – comes to call ‘the disastrous effect of the photographic flou ‘”.

The ironic side-effect of this situation was that pictorialist photographers suddenly had to explain that their images were “out of focus” for aesthetic, philosophical reasons and that they had a deep knowledge of the resources of their equipment. A totally different situation from the blurry images produced by Sunday photographers with their cheap cameras and wholesale developing/printing in some lab services. But they weren’t always successful in making this distinction.

Later on in the same article, Stieglitz describes the situation as photographers entered the 20th century: “In today’s photographic world, only three classes of photographers are recognized: the ignorant, the purely technical and the artistic. For photography, the first only brings what is not desirable; the second, a purely technical education obtained after years of study; and the third, brings the artist’s feeling and inspiration, to which purely technical knowledge is later added.”

This is how, at the beginning of the 20th century, practicality and quality became somewhat mutually exclusive in advanced amateur photography. Good photography had to be difficult in both senses, be it artistically, in the view of the pictorialists, or as pure photography or straight photography as it would later be called. The advanced amateurs, most of whom came from the aristocratic classes and the upper bourgeoisie, considered photography to be their territory, they were their legitimate representatives and those responsible for elevating it to the status of art. They rejected this new photography that was occasional, unambitious, banal in its themes, sloppy in its execution and made with cheap cameras. They didn’t want to be confused with these snap-shooters, a pejorative term they used to describe anyone who wasn’t as committed as they were.

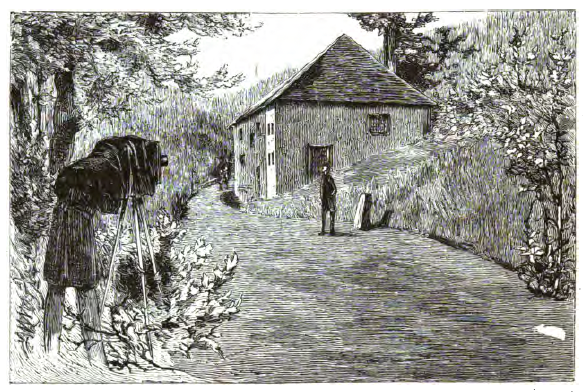

The creation and expansion of photo clubs is very significant of this split. It was an instrument for delimiting the territory between expert amateurs and simple photography users. According to Clement Cheroux, in the aforementioned Vernaculaires, in 1854 there was only one association in France, the“Société Française de Photographie (SFP). The 1880s saw the creation of the Société d’excursions des amateurs de photographie (SEAP, 1887), then the Photo-Club de Paris (1888). In 1892, there were 37 photographic societies; in 1901 there were 80 and the number reached 120 in 1907″. These were photographers who processed their photos, experimented with various printing media such as Gum, Vandyke Brown, Platinum, Cyanotype and Carbon, in addition to silver gelatine photographic papers, owned various cameras and optics generally for large format, and the vast majority of them stuck to the ancestral gesture of photography with tripods and glass plates. This type of camera is what we saw in most of the Zeiss Ikon catalog until 1927, in the previous room.

Bound by tradition

The equipment that corresponded to this segmentation of photographic practice limited the possibilities of photography for a few decades. The ceremonial taking of a photo with a large format glass plate camera, with a tripod, zero automation in the functions of framing/focusing, setting the shutter, loading the plate, could even be part of the professional photographer’s identity and ensure an expert image also for advanced amateurs, differentiating them from the crowd. There was an aspect of ritual reserved only for photography initiates. But it implied several limitations, because it privileged more static subjects, more orthogonal viewing angles, more favorable light conditions and other circumstances which, precisely for the amateur photographer, who at first would or could be exploring the limits of image production, seeking greater flexibility in photography, were just limitations that tied him to a tradition.

If they were asked about their choices, they would probably answer that large format with the best optics and rigorous processing were the safest paths to the quality images they were looking for.

The new horizons brought by Leica

Leica was the breakthrough in this dilemma between quality and easiness. If Kodak was bold in betting on photography for the masses, offering cameras and services to reduce the photographer’s involvement with the production of his images to a minimum, Leitz bet on amateurs who, on the contrary, sought to deepen this involvement as much as possible. It offered them more than a camera, but a “system”, with lenses, viewfinders, filters, rangefinders, stereo-adapters, enlargers, developing tanks, publications… a world and, to top it off, an expensive world, accessible to only a few. All this in the miniature format of perforated 35mm film. With a camera that could fit in a jacket pocket and accompany the photographer at all times. The success was immediate.

The vision of Oskar Barnack, the creator of Leica, was also to give lightness to the photographic act, but at the same time to offer and stimulate the photographer’s involvement in the search for mastery and maximum excellence in the quality of his images.

If you are in the themed circuit The Leica Revolution, use the buttons below to navigate through the rooms.