Rapid-Rectilinear | John Henry Dallmeyer

How the German John Henry Dallmeyer went to London and became one of the most respected names in the optical industry worldwide is something I’ve already covered in the article on the Triplet Achromatic. In the case of the Rapid-Rectilinear, the focus will be on how he came to design one of the most influential lenses in the development of photographic lenses. After Petzval’s famous portrait lens, the Rapid-Rectilinear was the next big leap that enabled enormous development in the sector.

The reason it was so important is that it was the first general-purpose lens. It had a medium aperture. It wasn’t as wide open as a Petzval for portraits, which went up to f/3.6, but it wasn’t as stopped as a landscape lens either, which maxed out at f/11 for focusing, but for actual photography needed to be further stopped down. The Rapid-Rectilinear’s aperture was around f/8.

Another important point for being a general-purpose lens was that it had an angle of view of 50 to 60º. Not as wide as landscape lenses, but much wider than portrait lenses.

These two characteristics, average aperture and angle of view, combined with the fact that the lens did not produce linear distortions due to its symmetry, allowed cameras to be built with a fixed lens. With a fixed lens they could dispense with the ground glass and frame through an external viewfinder, with the focus made by estimation, i.e. they could be used without a tripod. This opened up the possibility of instant photos, especially when dry plates appeared, which were much more sensitive than collodion. It was a revolutionary lens. It was licensed and copied by all manufacturers and dominated the market for more sophisticated optics until the first anastigmatic lenses were developed in the 1890s.

The basic design consists of two identical cemented doublets symmetrically positioned. Between the two is a diaphragm that was initially of the Waterhouse type and later an iris.

This Rapid Rectilinear came with a complete original set and a nice little leather case. This is rare with these lenses. There is no room for doubt as the serial number of the lens is also engraved on one of the Waterhouses. This serial number, according to Dallmeyer’s archives, indicates that this lens was manufactured between 1884 and 1888.

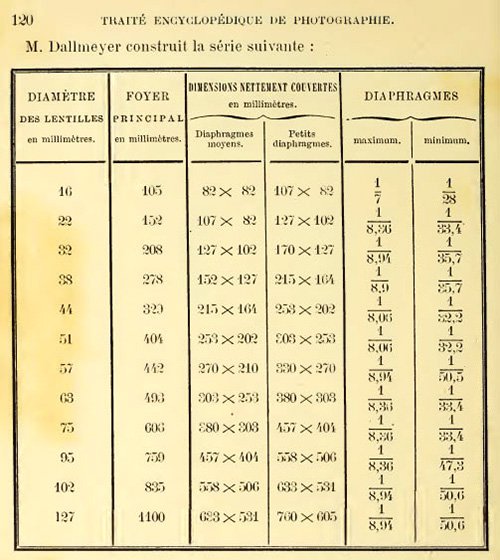

According to this table in Charles Fabre’s 1889 Traité Encyclopedique de Photographie Tomo I, being the lens in the collection a 44 mm (lens diameter), it is the one in the 5th row. So it has a focal length of 329 mm and makes a frame of 215 x 164 mm. The Waterhouses range from f/8 to f/32 (rounded).

The 8½ x 6½ inch format is engraved on the body of the lens, which corroborates Fabre’s table. It is therefore a lens for what was called a full plate in the Imperial System in the 19th century. Today I use it in 13×18 cm format.

Controversy with Steinheil

In the same year, 1866, a lens with the same concept of two equal and symmetrical achromatic doublets was launched in Munich. Designed by Hugo Adolph Steinheil, it was called the Aplanat. On hearing about the Rapid Rectilinear, Steinheil immediately accused Dallmeyer of having pirated his design and that the launch of the Rapid Rectilinear as Dallmeyer’s creation was a usurpation.

It’s understandable that Steinheil wouldn’t have thought otherwise, because in his case, the design of the Aplanat was a years-long project. He collaborated with his friend, the mathematician Ludwig von Seidel, from the University of Munich. They used a new formalism for dealing with aberrations in optical systems that had recently been developed by Seidel. When someone takes a very difficult and tortuous path to solve a problem, he starts to believe that nobody else could have taken the same route.

Today, it is accepted that this was a coincidence. Apart from the historical and documentary issues, there is a high probability that this was the case, as the styles and methods of Steinheil and Dallmeyer were completely opposite and illustrative of two currents within scientific work. If Steinheil was totally analytical and mathematical, Dallmeyer, trained by Andrew Ross, was much more into the empirical approach. Steinheil, only after convincing himself of his design in the formulas, must have tested his lens on prototypes. Dallmeyer started from his Triplet and probably used his experience and intuition to perfect the design more in the workshop than in mathematics. You could say that, each in their own way, the two reached the summit of the same mountain.