Niépce, Daguerre and the invention of photography

For a long time now, it has been accepted that the arrival of photography was a kind of collective work. Many people, from many parts of the world, contributed to the first steps and, above all, to the subsequent development of the processes, which were also manifold. However, it is impossible to deny that two people played central roles: Nicephore Niépce and Louis Daguerre. They teamed up in search of a technique, a procedure, for the permanent recording of camera obscura images.

Although they worked together in pursuit of the same goal, they represent two very different worlds that are still very different to this day. Observing the motivations and attitudes of each of them sheds a lot of light on what the invention of photography ultimately meant.

Nicephore Niépce

He was born into a wealthy family of bourgeois origin, but already possessed some privileges that only a noble family would normally have. His father was a court advocate, adviser to the king and in charge of government affairs in Chalon-sur-Saône. At that time, we can say that two types of aristocracy lived together in France. One was of medieval origin, knights, whose ancestors were invariably warriors and owners of large agrarian domains. The other was made up of families from the upper bourgeoisie who were granted titles of nobility by the king and contributed more to administrative roles than military ones (Louis XIV alone distributed titles of nobility to 20,000 families). More eclectic and more numerous than the traditional aristocrats, they were very well suited to acting as civil servants administering castles, customs, ports, possessions, estates and crown works. They had skills in liberal professions and business, as well as arms, which was practically the only skill required of a traditional aristocrat. Nicéphore Niépce’s family belonged to this second category.

What attests in practice that Nicéphore’s family had some noble status is the fact that they had to scatter and hide during the French Revolution when much of the court went to the guillotine. Nicéphore himself chose a military career in the army – this was shortly after his father’s death in 1792 (he was 27). His brother, Claude, did the same in the navy. It was a strategy to distract attention from the family’s aristocratic connections. But neither he nor his brother had any military vocation and both abandoned their careers when things cooled down. They both returned to Chalon to live in the comfortable house where they were born. The revolution took a large part of the family fortune, but what remained was still enough to continue living a good life as part of the Chalonaise élite.

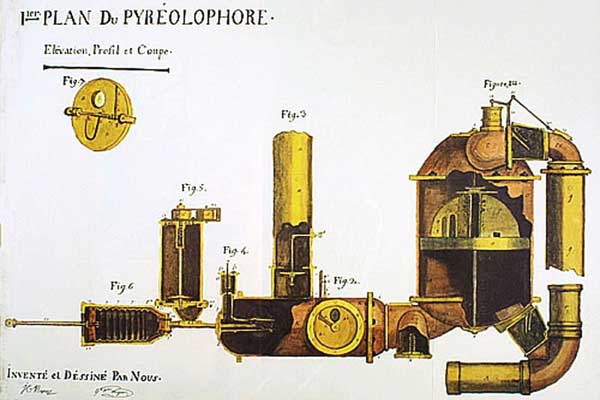

Nicéphore and Claude received a top-level education at the Peres de la Congregation de l’Oratoire seminary and even had a private tutor to supplement it. This solid education was certainly important for the brothers to decide to form a partnership dedicated to inventions and new technologies. The climate was very favorable. The mentality at the time was all about science, research, new machines and discoveries as a means to achieve general well-being in society, away from the tutelage of the aristocracy and the church. The two brothers embarked on a number of projects, the most famous and admirable of which was an internal combustion engine that powered experimental boats in Bercy – Paris, on the River Seine. The project was praised, seen as very promising and obtained a patent by Napoleonic decree, but … they never managed to make any money from it. Claude moved to London to sell it – motivated by the fact that what would come to be called the Industrial Revolution was accelerating in England and new machines usually attracted a lot of interest. But not even with English investors was it possible to start any business with the Pyreolophore – the name given to his invention.

Claude’s long stay in London (1817 to 1828) meant a further decline in the family’s financial conditions. In 1827, Nicéphéore also decided to go to London where he found his brother very ill and learned that there had never been any progress with the Pyreolophore project. Claude died in 1828.

First experiences with photography

A second purpose of Nicéphore’s trip to London was related to his experiments with what would later be called photography. After some success in sensitizing metal plates with bitumen for contact printing using sunlight, Nicéphore intended to submit his results to the Royal Society of London. There he met Francis Bauer, who was secretary of the Society, explained what he had done, what he wanted and was asked to write a report. Reading his report, (Fouquet p.149) it is easy to see that his approach was not very appealing to businessmen. First, he goes through all the shortcomings of his technique, all the unresolved problems, his uncertainties about untested materials, makes a secret of the procedures he uses, and then declares that he didn’t want to give England any advantage over any other country and that he was only there to get the opinion of this prestigious institution and safeguard by a public presentation the recognition of his priority in discovery. Well, not surprisingly, he didn’t manage to get accepted to present his invention at any of the Royal Society meetings. He brought samples of his photographs, made on metal plates, causing admiration among his interlocutors, but too much secrecy about the process and the lack of a clear proposal probably didn’t create the desired reaction.

What’s interesting about this brief recap of some of the facts of Nicéphore Niépce’s life is how he embodied all the ambiguities of his time. As a bourgeois, he defined himself as an entrepreneur. However, a life of business was something he really couldn’t bear, it would be too mundane for someone as refined and cultivated as he was. A military career, the most deep-rooted of all aristocratic vocations, was not his talent either. Becoming a dilettante living in isolation was therefore his choice. This would keep him away from universities, away from the court and away from business centers, away from all kinds of competitive environments, well in line with his aversion to social life. His choice was for a solitary, semi-scientific search for new technologies, which would never be fully developed – to this search he dedicated his life. We discover in Nicéphore Niépce much more a man of Romanticism than of the Enlightenment.

The idea of photography

Niépce was attracted to the subject of images when he learned about lithography. The process had recently been invented and in 1810 the first treatise on the subject was published in Stuttgart. This led to a rapid spread throughout Europe. Georges Potonniée, in his Histoire de la Découverte de la Photographie (p.84) gives the novelty a certain air of fashionable elegance: “in 1813, cultivated people were making lithographs, Niépce, like the others. And this discovery, which he saw as marvelous, made a deep impression on him”. Interested as he was in industrial processes, Niépce set himself the problem of arriving at a drawing made spontaneously by “natural forces”. This was the driving force and the first conception of his project.

A preliminary success was achieved by using a coating of Judean bitumen on a metal plate as a light-sensitive surface. The process was similar to etching. Artists used to cover copper plates with bitumen and then scrape them with a sharp instrument, the burin, exposing lines and patterns on the metal. Next, they used an acid that ate away at the metal and etched the design. The final step was to remove the bitumen, apply printing ink to the plate, which accumulated in the grooves corroded by the acid, and stamp the design on paper.

Niépce’s idea was to modify this process by observing that bitumen becomes less soluble after the action of light. Instead of scratching, he placed prints on paper over the bitumen coating and exposed them to sunlight. The white paper was made transparent by applying waxes and oils. The printed part acted as a barrier to the light. He then washed off the unexposed parts that were still soluble and the bitumen remained. This was a drawing engraved by light. The rest of the process consisted of applying acid, which would erode the dark, unexposed parts of the original drawing, and using the metal plate as a matrix for printing engravings. He called this process Heliography.

On the left, we see a well-preserved sample of this phase, on display at the Nicéphore Niépce Museum. This is from 1826, made on a tin plate, and represents Cardinal Georges d’Amboise. At the top we have the engraving on paper made transparent and backlit, in the middle we have the metal plate and at the bottom a final print. Niépce sent the plate to be printed in Paris by the renowned engraver Lemaître. Lemaître had to reinforce the grooves because the action of the acid had not been sufficient to retain the printing ink.

If Niépce had been an entrepreneur, he would have realized the excellent opportunity that the photo-mechanical reproduction of images represented for a new business. He would then have launched what he had already achieved in 1826 onto the market. But the light filtered through a hand-drawn picture was not the light he had in mind. So he moved on relentlessly to the next step, which was how to record the image in the camera obscura.

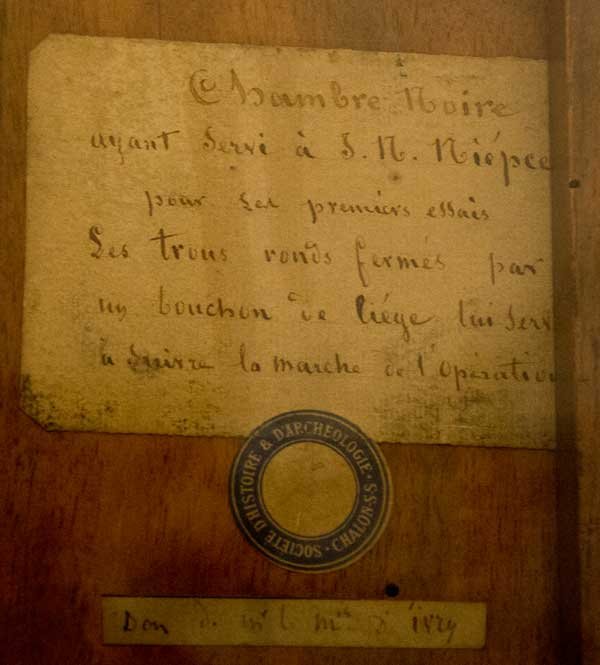

Nicephore Niépce Museum – Chalon-sur-Saône.

–

Inscription: “Camera obscura used by M. Niépce for his first experiments. The holes, closed with corks, allowed him to inspect the progress of the operation.”

–

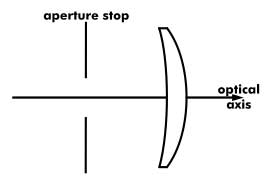

Above, one of the dark cameras used by Niépce. He hoped for a kind of direct printing effect (there was no concept of a developer for a latent image) and then punched two holes, usually closed with stoppers, to allow real-time observation of the image’s development. He used a Wollaston-type lens which was a simple meniscus offering f11 or f16, meaning a very dark image. His first success, still in existence, in capturing an image with a darkroom is the image below, a view from his window, the photograph dates from 1827 and required an exposure of 12 hours.

Gras à Saint-Loup de Varennes by Nicéphore Niépce – 1827

University of Austin – Texas – USA.

–

Wollaston lens – 1804 – the direction of light is from left to right

–

In fact, the invention of photography was very much the invention of the means to fix the photographic image. The principle of using an image formed by a lens and a light-sensitized surface was known for a long time. It is difficult to trace the first person to experiment with the effect. The Englishman Thomas Wedgwood (1771-1805) had already carried out tests in this direction in 1802, but “the images formed by means of a camera obscura were too weak to produce, in any moderate time, an effect on silver nitrate. To copy these images was Mr. Wedgwood’s first object in his researches on the subject, and for this purpose he first used the nitrate of silver, which had been mentioned to him by a friend, as a substance very sensitive to the influence of light, but all his numerous experiments as to their ultimate object were unsuccessful”(Eder p137). Even so, what Wedgwood was doing could well be called photography. What was still missing from his experiments was something to increase sensitivity and then a fixative.

Contact with Daguerre

Going back to Niépce, he experimented with many different substances, in particular he had high hopes for the use of phosphorus, but never got any results. If we think of combinations of supports such as tin, copper, silver … light-sensitive substances such as bitumen, phosphorus, iodine, in dilution with different oils, acids, or whatever, plus different times and concentrations, for all these processes, we can infer that Niépce spent thousands and thousands of hours on his experiments on a trial and error basis. There was no theoretical basis. He wasn’t really a scientist.

By the end of the 1920s, he was convinced that the quality of the images produced by his camera obscura was a problem. In 1826, he asked his cousin, who was going to Paris, to bring him several lenses from Vincent and Charles Chevalier, renowned opticians in those days(Fouque p117). This is how Charles Chevalier learned about the nature and results of Niépce’s research, and it seems that it was Charles Chevalier who established contact between Niépce and Louis Daguerre.

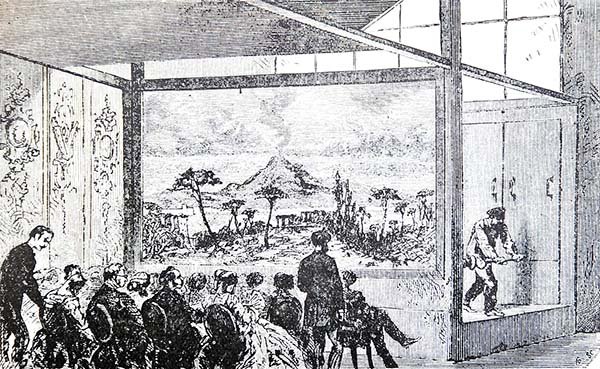

Exhibition of a Diorama

–

Daguerre was an artist, painter and entrepreneur working in a kind of entertainment business, the Diorama, which was a great success in Paris. It consisted of scenery that was lit from the front and back, with moving parts, a combination of real stage objects and backdrops and the effect was to be able to simulate environments with a dawn, daylight, sunset and other light effects. It would be what today we call an immersive experience.

In his History of Photography, Josef Maria Eder quotes a detailed description of a diorama session. It’s about a breakfast in a country setting:

There was no theater or backstage; we found ourselves under the eaves of a Swiss peasant house. Farm tools were scattered everywhere; it seemed that our unexpected arrival had frightened the timid residents. Below us, we could see a small courtyard surrounded by buildings. To our right, there was an open window from which some clothes were hanging to dry; there was a sawhorse and an axe, and some chopped wood was scattered under the stable doors; to our left, a goat was bleating, and not far away, the melodious sound of herd bells rang out softly.

Everyone stood motionless with amazement, but one surprise followed another. Behind us, wooden plates, spoons and glasses clinked. We turned and saw a young woman dressed in typical mountain attire serving a country breakfast of milk, cheese, dark bread and sausages, while a servant poured Madeira wine, port and champagne into crystal glasses.

But a little further on, what a view! The snow-covered valley was protected by the giants of the mountains. There was no longer any doubt about what we were looking at. I held out my hands and explained that ahead of us was Chamonix, at an altitude of over three thousand feet…

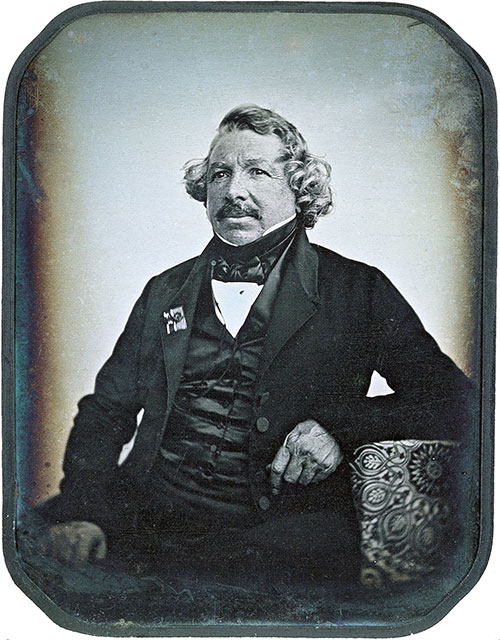

Daguerre’s portrait

–

The diorama was an immersive experience that included sounds, smells, tastes, touch and, above all, illusionistic visuals. The combination of real stage objects (a Swiss peasant’s house) with a dynamic painted backdrop with changing lights and colors (The valley, covered in snow) and even flesh and blood characters welcoming visitors (a young woman dressed in typical mountain garb serving breakfast), all in an environment where the visitor was not isolated, but part of the scene (there was no theater, no backstage). It was very convincing and overwhelming. Still in the description of the visit, quoted by Eder, there is an account of the reaction of a young English woman:

“This can’t be painting, its magic can’t go that far, there’s an extraordinary combination of art and nature here, producing an overwhelming effect, and it’s impossible to discern where nature ends and human skill begins. That house has been built, those trees are natural and on top of that… yes, on top of that, we’re lost. Where is the artist who created this?”

Daguerre approaches and it’s very interesting how he comments on his Diorama:

“Many art critics wanted to accuse me of the crime of mixing art and nature; they say that my live goat, my real pine trees and the peasant’s hut are artifices forbidden to the painter. Be that as it may! My only aim was to create illusion to the highest degree; I wanted to steal from nature, and that’s why I had to become a thief. If you visit Chamonix, you’ll find everything proven; the hut, the eaves and all the scenic elements you see here, even the goat below, which I imported from Chamonix.”

At the age of sixteen, Daguerre went to work in the studio of a well-known set painter called Degotti. From the outset, he showed great proficiency in mastering lighting effects. But in Beaux-Arts terms, painting scenery was not a very prestigious position in the hierarchy of painters. The canvas below is by him and is in the Louvre Museum, but I think it’s more for his celebrity in photography than for his career as an artist.

When he begins his comment with “Many art critics wanted to accuse me… ” it is clear that the high-art critics had objections to the Diorama. They considered it an artifice that went too far. Painting could or even should, in the view of many, be illusionistic, but the resources to which Daguerre resorted were considered exaggerated, even cheating. But his position makes it clear that Daguerre’s motivation was to deceive in the most convincing way. He wanted to enchant and surprise, and to do so he saw no limits. With this disposition, he certainly looked at the possibility of photography imagining the impact it would have on the general public, not on academies or salons of fine art. As with his Diorama, he later thought about photography with the general public in mind, whom he knew so well.

The collaboration contract

Daguerre approached Niépce, and the latter rushed to get references from the engraver Lamaître(letter of Jan/1827 – Fouque p126 ): “Do you know one of the inventors of the Diorama, this Mr. Daguerre? The reason I’m asking is that this gentleman, informed, I don’t know very well how, about the subject of my research, wrote to me last year, in January, to inform me that he had been researching the same thing as me for a long time and asked me if I had been happier than him in my results. However, according to him, he had already achieved something very impressive and, moreover, he asked me to tell him, first of all, if I thought the whole idea was possible. I won’t hide the fact, sir, that such an inconsistency of ideas had the effect of surprising me, to say the least.”

Niépce and Daguerre’s meeting and cooperation were compromised from the outset by the enormous secrecy each maintained about the real status of their research. Each overestimated the level of knowledge and development that the other apparently had on the subject. Daguerre believed that Niépce would already have something much more effective than bitumen prints and Niépce, in turn, believed that Daguerre would be able to provide a magical camera, with marvelous optics, capable of compensating for all the disadvantages of sensitivity that his process still presented. In any case, they signed a contract in 1829 and, on that condition, had to share what they actually had.

It was a mutual disappointment. However, to be fair, it has to be said that Niepce did have something with his heliographic process, while Daguerre added nothing that Niepce couldn’t get from opticians like Charles Chevalier or others. Eder says it clearly: “It is worth noting that Niepce met Daguerre bringing his invention which was really new, but that Daguerre had no important photographic contribution to offer”(Eder p223).

The terms of the agreement, in the partnership contract between Daguerre and Niépce, clearly state that Heliography was already “the” discovery, that it only needed improvements, and that it would be up to Daguerre to bring about these improvements. We read: “M. Daguerre, to whom he [Niépce] divulged his invention, fully realizing its value, since the invention is liable to receive great improvements, offers to join M. Niepce in achieving this perfection and obtaining all the possible advantages of this new industry”. There is a complete English translation of this agreement in Eder (p215). The original is reproduced by Fouquet (p161).

Niépce’s death

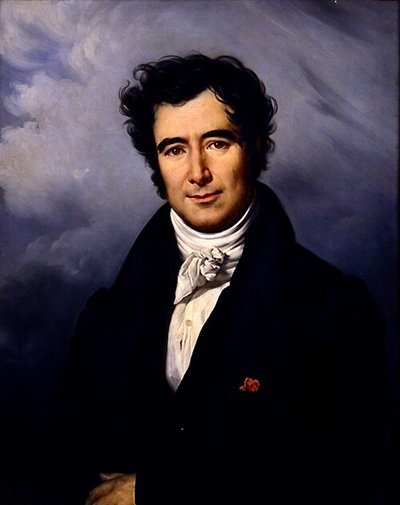

Nicéphore Niépce posthumous portrait painted in 1854 by French artist Léonard François Berger

–

Niépce died in 1833 at the age of 68 and his son Isidore took over his share of the contract. Daguerre was then 46 and continued his research, which as we know was not long in showing results. The process that ended up bearing his name instead of Niépce-Daguerre, as was the initial agreement, has always been widely referred to as a case of usurpation. Isidore, Nicéphore’s son, wrote a small book ” Post tenebras lux. Historique de la découverte improprement nommée Daguerréotype” (p47) (After darkness comes light. History of the discovery improperly called daguerreotype) in which, among many other considerations, he brings up a specific clause in his father’s contract which reads as follows: “in the event of the death of one of the associates, the discovery mentioned will never be announced without having the two names designated in the first article”. This is quite clear and strong, but Daguerre also had his arguments. The fact is that his technique using silver plates sensitized by iodine and with a latent image developed by mercury was something really different from what Niépce had come up with.

It is also true that Daguerre insisted that Niépce should try iodine and the latter, after several tests, replied back saying that he had completely given up on this substance. In a letter of November 8, 1831 to Daguerre, Niépce says: “I have made a great number of experiments with iodine in combination with silver plates, without at any time obtaining the results that the means of deoxidation would have led me to expect. Despite all the changes to which I subjected the procedure and all the various combinations of different test methods, my success was no more fortunate. […] After a few other trials, I remained at this point, and I must confess that I am extremely sorry to have pursued a wrong direction for so long, and what is worse, to no avail … ” (Eder p.225)

So Daguerre persevered on a path that Niépce had abandoned. He later considered the discovery to be his alone and so forced Isidore to sign an addendum to the provisional contract of 1829 changing the name of the association, establishing himself as the first. That was in 1835. Later, in January 1837, Daguerre, more assertive, again pressured Isidore to sign a definitive contract, preparing the announcement of the discovery and the commercial strategy to finally exploit the invention. Daguerre’s proposal was a split: announce what Niépce had done, Heliography as Niépce’s only and the new procedure would be called daguerreotype. Isidore himself explains how Daguerre put the situation and why he gave in: “Annoyed by my constant refusal, he declared that if I didn’t agree to his request, he would keep his technique to himself [Isidore had seen daguerreotypes and was, as anyone would be, very impressed]. So we would only publish M. Niepce’s process, and later he would publish his own, which would prevent me from taking even the slightest advantage of my father’s discovery. I remarked that such an action was contrary to the rights stipulated in the act of association: he replied that his procedure had nothing in common with my father’s and that he was free to keep it secret! “.(Isidore Niépce)

Well, Isidore signed the new contract and together they began a commercial launch through a system of selling the rights of use and all the information necessary for the buyer to go into production of their own daguerreotypes. They planned to raise between two and four hundred thousand francs. So for one individual this would mean the significant sum of two to four thousand francs for a number of hundred shareholders. But there isn’t much documentation available of how many quota holders they were aiming for.

But nobody wanted to buy it. Among the factors for the failure, there is no doubt that the investment was high, the difficulty of selling a secret because the person doesn’t know for sure what they are buying, the suspicion that the secret would become public sooner or later and, finally, we must consider that photography didn’t exist yet, that is, people weren’t rejecting the invention of the century, they were unmotivated to buy a trick that recorded the images of the camera obscura on a metal plate. That was all for the time being. No one knew, or apparently even imagined, what photography would become.

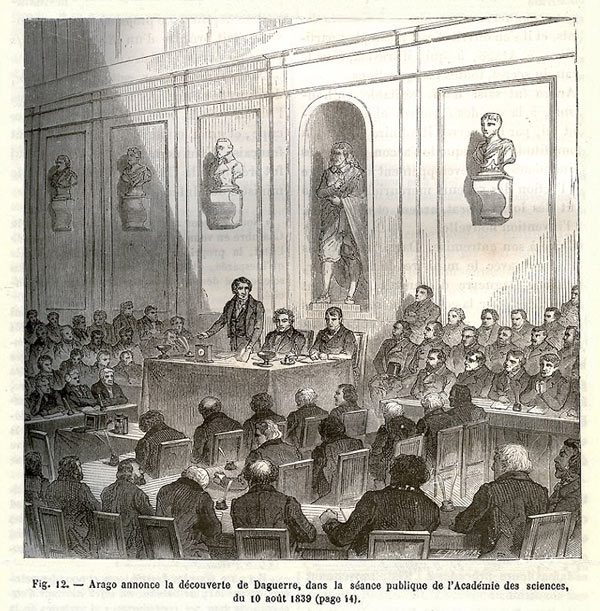

Daguerre must have had a fantastic network through his Diorama, as it was one of the great attractions in Paris at the time. Unimpressed by the “market’s” discouragement with his invention, but still certain that he had something precious in his hands, he turned to the Academy of Sciences, looking more specifically for the right person: Dominique François Jean Arago.

The Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences was going through some tensions and transformations at the time. There were two ways of looking at the role of the Academy and the sciences in relation to the state and society.

On one side was François Arago. Born in 1786, he was something of a child prodigy who joined the Academy at just 23. His contributions to research into optics and electromagnetism were significant. When Daguerre sought him out, he held the highly influential post of Perpetual Secretary of the mathematical sciences section (which included physics and astronomy). This position, in practice, made him the chief executive and spokesman for an important part of the Academy, giving him significant power to set agendas and influence proceedings.

Dominique François Jean Arago (1886 – 1856)

–

In this position, he was changing life at the Academy. His vision was that the institution should be accessible to all and not remain a closed circle. He opened up many sessions to the lay public and openly published the minutes. He invited people from industry to present and debate on various topics. Finally, he believed it was the role of the state to proactively promote progress, not only scientific but also technological.

Who could be against it? Well, there was the conservative wing headed by his former research friend and now great rival Jean-Baptiste Biot. For Biot, science was serious business, to be discussed only by the academic elite. Its themes should be basic research into the great laws of the universe and never be reduced to solving problems of industrial processes and the like. For Biot, what Arago was doing was vulgarizing and spectacularizing science, distorting it from its noble purpose.

Needless to say, Daguerre knocked on the right door. Arago was immediately enthusiastic about the Daguerreotype and became its main and most influential advocate. Their plan was that the French government would buy the invention and give it to the world, i.e. the procedures would be publicized and anyone could make their own daguerreotypes without having to pay anyone anything.

Daguerre approached Arago at the end of 1838 and the latter used the session of January 7, 1839 to announce that the problem of recording the images from the camera obscura had been solved.

His speech is very short and boils down to the following points:

1- Everyone knows about the Camera Obscura and has thought how nice it would be if its perfect images could be preserved.

2- This frustration will no longer exist, as Daguerre developed a screen on which the optical image leaves a perfect and permanent impression.

3- He clarifies that they are not color prints but that they register in shades of gray as if they were an aquatint engraving.

4- He says that he submitted proofs of various views of Paris to his colleagues Humboldt and Biot and that the exposure time on a sunny day varies between 8 and 10 minutes.

5- He points out that the image is correct about light and dark, unlike previous experiments with paper impregnated with silver chloride used to make silhouettes in which the bright was dark and the other way around.

6- He talks about the uses that can be made, such as recording monuments and also in the sciences of physics and astronomy.

7- He talks about the time and investment that Daguerre and the Niepces (father and son) made to arrive at this brilliant discovery and that a patent would not guarantee fair remuneration because once the secret is revealed, it will be available to everyone.

8-He states that he considers it “indispensable” for the French government to “compensate” Daguerre directly and then “nobly” donate the invention to the whole world.

9- Biot then took the floor and fully endorsed what Arago had just said. He stressed that he saw the Daguerreotype as an artificial retina that could provide images without interpretation bias and therefore ideal for the sciences. It was very politic of Arago to bring Biot, his arch-rival, to support the Daguerreotype and thus shield the invention from the Academy’s internal disputes.

An invention with many pioneers

The news that the respected French Academy of Sciences was going to ask the government to buy the rights to the invention of the daguerreotype, the process capable of recording images from the camera obscura, caused tremors around the world. The first reaction was an avalanche of requests for recognition of pioneering spirit from many other suitors.

If so many others had already come so close or actually obtained a stable photographic image, why didn’t it have the repercussions that the daguerreotype had? To answer this question, first we need to erase from our minds everything we know about the future of photography after 1839. Photography didn’t exist and those who researched it didn’t necessarily realize what they were researching.

It’s enough to remember that at the end of 1838 Daguerre himself tried to sell the method and exhibited his undisputed copies to the cream of Parisian society, but nobody wanted to buy. Before 1839, “photography” was a curiosity, an enigma to be solved, a distraction for educated and wealthy gentlemen who still had other occupations. When Talbot, one of the complainers, comments on the interruption in research after 1835, he says that he had no time for “leisure” activities. At that stage, it was simply a leisure activity. He didn’t feel as if he was working on an invention that would change the world.

Those who had any reasonable results in inventing photography, what did they do? The ones we know made practically private use of it, shared it with their immediate surroundings, did some experimentation and were satisfied. None of them opened a studio or went out into the world recording its beauty. None went out shouting “I invented photography”. If they did, nobody paid much attention and, it seems, they sat on their inventions. One exception was Louis Daguerre.

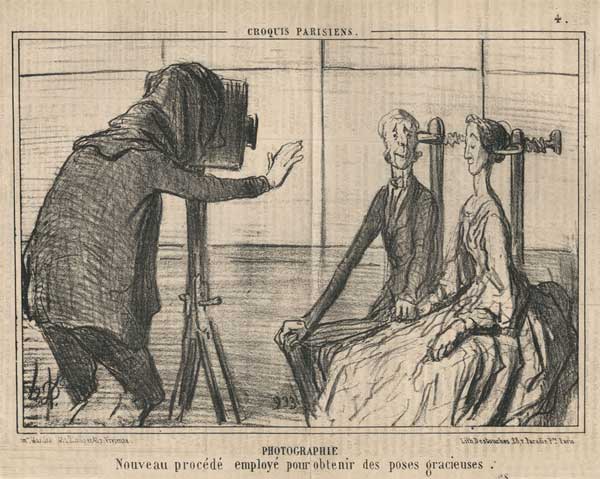

Daguerre was someone who dealt with the general public in an illusionist business, as we saw above, like his Diorama. He had this intuition that in marketing is called “consumer insight”. He had a premonitory vision of photography as it would become. His motivation, right from the start, was to do something great, not just solve a riddle and make his friends jealous. He didn’t just want to be ecstatic about his own achievement. In a pamphlet from the end of 1838, promoting the signature system, we can clearly see where the invention of photography, as we know it, actually was born. It wasn’t in optics or chemistry, it was in the perception of what it could mean for people and society.

With this process, without any notion of drawing, without any knowledge of chemistry or physics, in a few minutes you can obtain the most detailed images, the most picturesque places, because the means of execution are simple, they don’t require any special knowledge to be practiced, a little care is enough and with habit you can perfectly succeed.

Everyone, with the help of the Daguerreotype, will be able to take a view of their castle or country house, to form precious collections of all kinds that even art cannot imitate in terms of detail and accuracy, and which are unalterable in the light. It will even be possible to make portraits, even if the mobility of the subject poses some difficulties for complete success.

This important discovery, susceptible to all applications, will not only be of interest to the sciences but will also give a new impetus to the arts and far from harming those who practice it, it will be of great use to them. People all over the world will find it the most attractive occupation, and even if the result is obtained with the help of chemical means, this little work will be able to please quite a few ladies.

Finally, the Daguerreotype is not an instrument that allows you to draw nature, but a physical-chemical procedure that gives nature the facility to reproduce itself.

It’s impossible to imagine the erudite Fox Talbot writing something similar. François Brunet, in his book La naissance de l’idée de photographie, says, with a certain contempt, that Daguerre uses a “street vendor’s argument” in his pamphlet. It’s really like a street vendor shouting: it’s so easy, look at all the wonderful things you can do with the daguerreotype. In this short text, we can already imagine the weekend photographers, collections of photographs, the photo of the house, the family, the dog, the portrait of the loved one. In short, we can already see a bit of the George Eastman spirit in this pamphlet.

Daguerre was neither a scientist nor a scholar. The discovery of the key step in his process, the bath in mercury vapor, was discovered completely by chance. Eder tells us that he had given up on some silver plates bathed in iodine vapor and kept them in a cupboard. A few days later, rummaging through the cupboard, he was shocked to see that the images were there in some plates. He suspected that something was inside the cupboard, which was actually full of the most diverse materials. He eliminated them one by one until he identified a small pot of mercury as the culprit. Well, that’s not the scientific method. Trial and error is part of science, but trials are usually informed, based on a hypothesis, a model. In Daguerre’s case, on the technical side, what he had was a lot of perseverance and a lot of luck. What wasn’t luck, and full or merit, was his vision of how photography would change the world.

He was also very fortunate to seek out François Arago, as photography fitted in perfectly with the agenda of the Perpetual Secretary of the Academy of Sciences. It would be a perfect example of the Academy and the French government as a whole taking the lead in encouraging a fusion of science and technology for the progress of the nation. Photography, because of its possibilities for scientific and artistic use, as Arago demonstrated and even his enemy Biot pointed out, was the perfect invention to materialize this marriage.

For the many candidates for inventor of photography, who immediately after the announcement on January 7, 1839 rushed to prepare their dossiers to send to the Academy, it was as if they were saying: “I had invented photography, but I didn’t know it was important”. The award of a life pension of 6,000 francs a year to Daguerre and 4,000 to Isidore woke the world up. François Arago endorsed Daguerre’s invention and vision and the weight of his authority made all the difference.

A trade in photographic equipment began, cameras, lenses, books, chemicals and all sorts of other paraphernalia. Studios were opened and, very importantly, various improvements to the process were made by photographers and scholars. The most significant of these was undoubtedly the generous contribution of the Englishman Sir John Herschel, who indicated that sodium thiosulphate would be a more efficient fixative and thus ensured a de facto permanence for the photographic medium.

The Daguerreotype was a kind of awakening for photography. But it didn’t last long. The 1850s saw the arrival of the collodion-on-glass process for negatives and the albumen-on-paper process for prints, and these dominated until the arrival of gelatine as a suspension medium for silver halides. This was at the end of the 1870s, and was a direct development of Fox Talbot’s calotype.

Louis Daguerre’s image suffered a good deal of wear and tear. While Nicephore Niépce was easily connected to a solitary genius working alone, tirelessly in his mansion in Shalon-sur-Saône and without having seen the fruits of a life of dedication, very much along the lines of the romantic hero, Daguerre was associated with the malicious capitalist businessman who appropriated the discovery and even took the name, tried to erase the contribution of Niépce, his former partner, denying him the posterity to which he was fully entitled.

In short, as it was pointed at the beginning, photography was a collective work involving various types of actors. The discovery of the natural properties of the chemical elements involved, plus the invention of devices and processes that could take advantage of these properties in the production of images, plus the perception of the scope that the new resource would have in people’s lives, all this required many different talents, a lot of creativity and a lot of work.