The story of the Lerebours

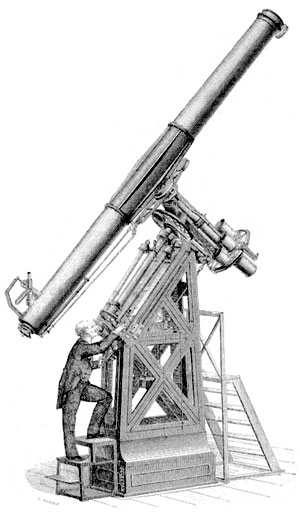

Objectif Achromatique – manufactured by the firm Lerebours et Secretan around 1855

–

The story of the Lerebours, manufacturers of optical instruments in Paris at the time of the invention of photography, is so interesting that it’s worth taking a moment to learn about its founders. In this way, we can better understand the profound transformations that Europe was going through in the 19th century. These are considerations about cultural changes that are organically linked to the advent of photography when we look at it from a more general perspective. Photography was one of the fields in which a very important change in values, brought about by the bourgeois revolution, clearly manifested itself.

The founder

Jean-Noel Lerebours arrived in Paris with his family from Normandy at the age of 12 in 1773. Jean-Noel had four brothers and his father was a hat maker. As soon as he arrived in the capital, he became an apprentice in a workshop dedicated to making glasses. At the time, this industry was growing very quickly, driven by the spread of the press, books, periodicals and the appreciation of culture. It was, for example, when the great art museums opened to the general public.

Jean-Noel soon moves to an optician’s workshop owned by a certain Louvel, where he stays until he is 18. At this time, his father died and he, as the new head of the family and responsible for his mother and younger siblings, began an entrepreneurial career. He buys the tools to polish lenses and starts accepting orders from the best opticians in encouraging quantities. Business is good, Jean-Noel lives austerely and works hard. There was a great demand for telescopes, both astronomical and terrestrial, and the Lerebours firm established its name and grew among French manufacturers. Competition was strong and the better reputation of English instruments forced a much lower price for local manufacturers.

The telescope on the left gives a good idea of the level of expertise and technical capacity that the Lerebours firm reached in its maturity. Manufactured in 1823, it had a lens with a diameter of 24 cm and a focal length of 323 cm. The diameter of the lens is a kind of certificate of competence for a telescope maker. A 24 cm objective lens is an imposing landmark even today. This telescope was immediately acquired by the Paris Observatory. Jean-Noel was honored with numerous awards, medals and titles such as Opticien du Premier Consul, then Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. He was later made Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur by Louis XVIII,

Governments were fully aware that technology would determine the power and competitiveness of nations. When Jean-Noel started with his first telescopes, he used English flint glass, but over the course of development, in collaboration with other members of the local industry, he began to use French glass and achieve parity in quality with British manufacturers. To stimulate rapid development and its positive implications for the national economy, there was a network of information exchange, collaborations, awards and dissemination of technological achievements. Institutions such as the Academy of Sciences, the Society for the Encouragement of National Industry and the Universal Exhibitions fulfilled this role of fostering an environment eager to absorb new technologies. Manufacturers competed for medals to endorse the quality of their production and cash prizes were offered to anyone who came up with solutions to the most pressing problems of the time, both in basic science and industry. This was new and totally different from artisanal production and feudal organization in guilds and sectoral associations whose aim was to always do things the way they had always been done. It was only at this time that a collaboration was born between university and industry, between scientists and entrepreneurs, valuing doing things differently, productivity, the new over the traditional – in the article on the Petzval lens, the case of the development of this optic for portraits is analyzed from this angle of how science finally met technology – link: The Petzval Lens.

Jean-Noel Lerebours became a widower and moved in with a seamstress who was the mother of Noël-Marie Paymal, the son of an unknown father. The boy soon became interested in business and joined the firm, which was already a major company in its field. In 1836, Jean-Noel officially married and made Noël-Marie Paymal, now also Lerebours, his heir. With his adoptive father’s death in 1840, he would continue and expand the firm’s business to an even greater scale, as with the invention of photography the optical industry experienced growth that had previously been unimaginable.

The importance and prestige of the optics and photography industry, in the form of two of its leading brands, can be gauged by considering that Lerebours and Chevalier (another renowned optician and manufacturer) set up shop in one of Paris’ noblest spots, on the Place du Pont Neuf. The building on the left, pictured above, housed Lerebours’ store and studio and on the right was the Chevalier maison. Below, the current view of the buildings.

Noël-Marie Paymal Lerebours was a key figure in the development of photography. Not only did he manufacture lenses, cameras and accessories for the field, studio and laboratory, but he was himself a great daguerreotypist, publisher and influencer in all the developments, dissemination and uses of the new invention.

Shortly after the announcement of the daguerreotype in 1839, when the process was bought by the French government and released into the public domain, Daguerre and Isidore Niépce signed a contract with Alphonse Giroux, a merchant and manufacturer of fine joinery, for him to produce the only cameras authorized to bear Daguerre’s seal/name. But immediately, Noël Paymal Lerebours, who had no shortage of prestige as an optician and manufacturer of scientific instruments, also started manufacturing cameras and all the apparatus needed to produce daguerreotypes.

Like Giroux, he also published a brochure entitled“Historique et description des procédés du daguerreotype et du diorama – Rédigés par Daguerre et ornés du portrait de l’auter“. To Daguerre’s official text, presented in the proceedings at the Academy of Sciences and which earned him a good pension for life, Lerebours adds his notes and observations on the process. The publication was a great success and had several subsequent editions.

An initiative that still guarantees him a special place in these early days of photography was the publication of Excursions daguerriennes, with the pompous subtitle vues et monuments les plus remarquables du Globe . There were two books (1841 and 1843) with prints made from daguerreotypes of collaborators and Lerebours himself. Views of France, Egypt, Italy, Russia, Algeria and even Niagara Falls are reproduced through prints made from daguerreotypes. The process of transferring the photo to the print was partly mechanical, using the daguerreotype’s own metal plate, and partly manual. It is true that, by looking at the images, the engraver made a good contribution based on what he knew of drawing and composition techniques.

The scene below, taken from Excursions Daguerriennes, shows the castle of Fontainebleau. We can be sure that a Daguerreotype wouldn’t be able to reproduce marching horses. But these elements added after the fact gave balance and life to the scene. The clouds too, so difficult to reproduce in a process that is only sensitive to blue and ultraviolet, were probably added by the artist.

But these details probably didn’t bother the realism or authenticity of the scenes depicted. At a time when short trips were difficult or impossible for most people, being able to see “photographs” of Roman ruins, churches in Moscow and mosques in the Maghreb must have been magical in itself.

As nobody had seen what photography was, because it didn’t exist, what these pioneers did immediately took on the identity of the new medium. They became canonical and determined what photography would be for decades to come. Which subjects, which points of view, which perspectives, how to arrange the foreground, how to organize the scale of things, all these aesthetic issues were being established and were largely not new but borrowed from painting and the arts. A certain autonomy for photography would only come in the 20th century.

Lerebours and his collaborators were very active in establishing these canons. In 1841, less than two years after the announcement of photography, Lerebours published a Treatise on Photography together with Marc Antoine Gaudin, in which he once again presented the daguerreotype process, with some modifications, and also discussed portraiture, the choice of backgrounds, poses and clothing, landscape, still life and other issues that formed the understanding of what and how photography should be. In 1841, Lerebours reported having made more than 1,500 daguerreotypes. His output would soon reach the same number of portraits in just two months. Number 13 on the Place du Pont Neuf became the place where Parisian photographers met to discuss, share and compare their results in photography.

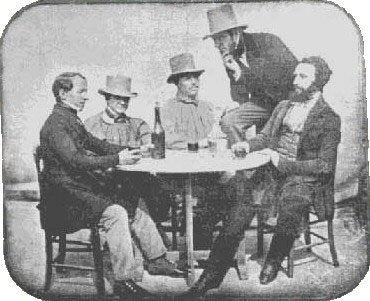

The photo above shows Noël-Marie Paymal Lerebours on the left. Standing is the German Friederich von Martens, who worked for Lerebours and developed a rotating-lens panoramic camera – more information on this type of camera can be found at this link. On the right is Marc Antoine Gaudin. The other two seated, wearing hats, are unknown and are probably employees of the Lerebours company.

In 1845 Noël-Marie joined forces with Marc Secrétan, a mathematician and astronomer. They changed the name of the firm to Lerebours et Secrétan. Lerebours dedicated himself more to the photographic sector and Secrétan developed the firm’s original vocation in the manufacture of telescopes and scientific optical instruments. The union is very fruitful and gives the company a new impetus. Secrétan, a Swiss who had just arrived in Paris, soon found his place and made a name for himself among the leading scientists of the time. The association lasted until 1855 when Lerebours retired, leaving behind a company of international fame and high market value. Secrétan then gave the production of lenses a more scientific and less empirical character. He introduced more calculation and mathematics as the basis for designs and developments. In the hands of other heirs, the company continued, but it left the Place du Pont Neuf in the 1870s and would never again experience the glory days of Lerebours. The brand remained active until the 1950s.

The new order that the Lerebours saw born

What’s interesting about this story, apart from its novelistic aspects, is the change in way of life that was brought about by the Bourgeois Revolution and the whole ideology of the Enlightenment. The key point is the prominent place they gave to scientific knowledge. The impact of these transformations was enormous on the whole dynamic of society. For centuries and centuries, the chance that someone born into a humble family had of achieving a position of leadership was basically through arms. All the European nobility that formed from the end of the Roman Empire was militaristic. If the individual was a commoner, but very good at killing his peers and leading wars and pillages, he would eventually become a general, a little king or even a great emperor. The ecclesiastical route, another option towards power, was soon occupied by good families and only a charismatic and politically savvy preacher could, coming from a humble background, achieve notoriety in the hierarchy of the Roman Church. There was also commerce, the very cradle of the bourgeoisie, but being a merchant or banker, even a very successful one, didn’t exactly make someone praised and honored. They were seen, at best, as a necessary evil and were unable, no matter how much they donated to building churches and financing wars, to have their way of life elevated to the model condition that the lives of nobles and saints were.

What the Enlightenment achieved, as part of the modernity package, was to give a positive conceptual basis to manufacturing, to work, to the transformation of nature into goods and wealth, which these activities never had. Looting, seizing, collecting taxes, and all the coercive ways of getting rich have always been considered much more noble than working. What gave manufacturing this veneer of honorable activity, somewhat distanced from manual and repetitive labor, was inventiveness, creation, study, scientific knowledge at the service of the mastery of nature and the production of goods. To the old typology of models of our Western culture, basically made up of the warrior, the religious and the artist, was added the scientist and his entrepreneurial colleague, the new creators of wealth.

Photography is truly exemplary as part of this transformation. In optics and chemistry, the leaps in the scientificization/industrialization of an activity that had previously been artisanal are very evident. The notoriety gained by the Lerebours, father and son, the journey they made, starting with the simple polishing of spectacle lenses, then moving on to the top astronomy circles of their time and even as a “knight of the king’s legion of honor”, is a classic case of this transition that added calculation to the manual. Lerebours son’s understanding of this transition is attested to by his association with the mathematician Secrétan. The success of Petzval’s lens, another mathematician, called into question the method of intuition with trial and error, which was the modus operandi of great opticians such as Charles Chevalier and Jean-Marie Lerebours. Even Niepce, Daguerre, Talbot and Florence cannot be considered much more than dilettantes. Their merits lie more in having been visionaries and very stubborn. But soon photographic processes became the subject of names like John Herschel, and their processes came to be seen as part of a body of knowledge that was being developed in basic chemistry research and then cascaded into technological processes.

Stories like that of the Lerebours are added to thousands of others in which work and study won not only financial comfort, as the haute bourgeoisie had always had, but also respect and admiration from society, as the haute bourgeoisie had never had before. It was like a new way up the social ladder that was open to everyone through work and study. The 19th century saw many misfortunes and social upheavals, but there was also a climate of euphoria and confidence in the future. This new social order was an encouragement to those who were balancing on the bangs of prosperity but without participating in it, something like eternal salvation had been during the Middle Ages.