Cartes de Visite

The Carte de Visite, CDV, was basically a defined format of photograph pasted onto a cardboard support. The usual dimensions were: 54 × 89 mm, 2.125 x 3.5″ for the photo and 64 × 100 mm, 2.5 x 4″ for the card. It may seem strange that this type of photography was an “invention”, but its creator, the Frenchman André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, went far beyond the format itself. In 1854, he developed and patented the entire process, from taking the photo to how to paste it onto the card.

But it would be very difficult to enforce his rights, as the end result could be obtained using methods that were sufficiently different not to constitute infringement of his patent. Although he even sued some photographers, his rights were soon ignored and the CDVs spread all over the world to no avail for their creator. On the other hand, with his work as a photographer alone, Disdéri became extremely wealthy and for some years was among the most sought-after photographers in Europe. However, he was more of an inventor than a good administrator. For example, in addition to the CDV, he created a TLR (Twin Lens Reflex) camera, a concept that would become the famous Rolleiflex in the 20th century. But because he spent more than he earned, he ended his life in poverty. He had to sell everything and went to work as a simple photographer in third-party studios.

The CDV process

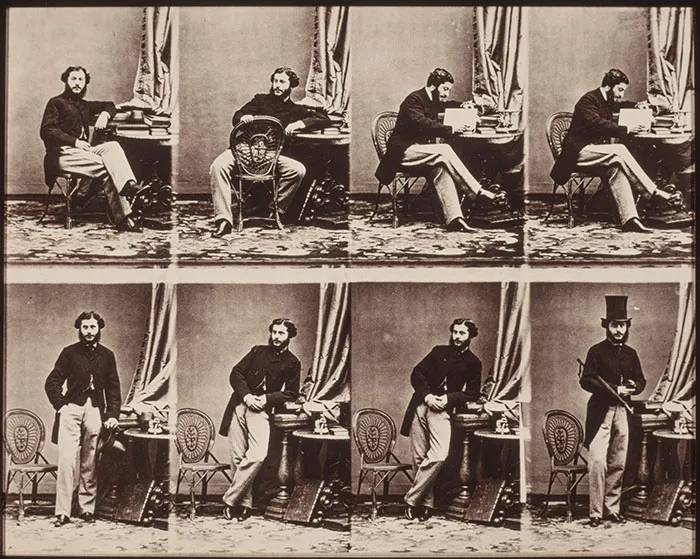

The camera had something special for productivity. It had 4 lenses that could be operated independently. At the rear, a sliding chassis made it possible to take two series of 4 photos. Thus, on a single wet collodion plate, with a single processing, the 8 photos were obtained and the customer could choose as many copies as they wanted of each one individually.

Camera for 4 photos in CDV format. Above is the front panel with the four lenses and below is the back of the camera with the dividers so that the light from one photo doesn’t fall on the neighboring ones.

–

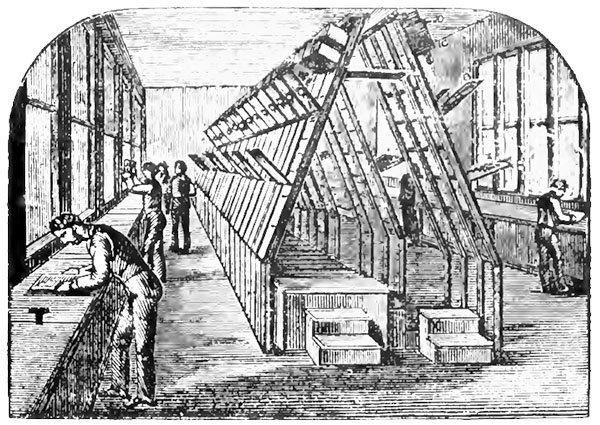

Printing was done by contact on very thin paper using the albumin process. This produced the characteristic brown color of CDVs. From the 1880s onwards, carbon printing gained importance. It’s a much more permanent process, even more beautiful because it produces details both in the shadows, with very dense blacks, and in the high lights. However, it is also more labor-intensive, therefore more expensive, and it didn’t drive out albumen once and for all. Carbon printing became the luxury version of photography, second only to platinotype. But the latter was rarely used on Cartes de Visite.

In the large studios, a room with high windows was reserved for contact presses that used daylight, which is rich in ultraviolet and therefore best suited to processes such as albumin or carbon.

Once printed, in one or several print runs, each photo was cut out and glued to the card, which usually had the photographer’s details printed on it. It was up to the client whether or not to add their name or a dedication. Some photographers were very discreet and only put their name on the card. Invariably, with the exception of traveling photographers, they also included the studio’s address. The space on the back was also used to give some kind of endorsement to the photographer. Many Carte de Visite feature medals. These refer to exhibitions in which the studio took part and won awards. For example, the detail above reads: Universal exhibition Paris 1878, silver medal. Another popular promotional feature was the reference to important clients: photographer to the King of Belgium or former assistant to the photographer xyz.

The studios became real industries and were positioned in the most sophisticated and busy addresses in the big cities. They employed many operators for each stage of the process. The photographer himself was more of a stage director and the manual part was left to his staff and assistants. Of course, this varied according to the demands of each studio. As the process itself wasn’t so complicated, there were also photographers who worked alone and even in an itinerant system, traveling around smaller towns.

Disdéri – Proof of a plate with Cartes de Visite – Eastman Museum Collection

Cartomania

In the early days of photography there was talk of daguerreotypomania, the Cartes de Visite were that and much, much more. The relatively low price and infinite reproducibility made CDVs a kind of pandemic, something the daguerreotype could never have achieved.

I’m going to reproduce a long quote from an article in the French newspaper Le Monde Illustré, dated November 3, 1860. The text is signed by Jules Lecomte and the subject is what Parisians were doing on their return from summer vacation. It’s a humorous text, a satire of society, and it’s an excellent source for understanding the extent and use of the CDVs.

What are the Parisians doing back home and the world still doesn’t know?

The question is somewhat confusing, diffuse, multiple, vague and complicated. To answer it, I’ll take a part for the whole and look around me at what’s going on in my relationships. The women who come back from the spa, the castles, the grape harvest or the marital hunts, take advantage of the sun and flirt. They go to see what has been demolished and rebuilt in Paris in the last six months; – they go to inspect the new stores, have the fabrics unfolded, saying that they will decide later… […]

Then, in the evening, they have dinner with some close people, whom they question about this or that, about everything… Finally, they catch up; they talk about marriages and break-ups, – fortunes made or lost; – above all, they avoid talking politics in order to remain friendly and cordial. Finally, in the evening, they go to see what’s on at the theaters, – or they dedicate themselves to the new fashion, already almost a rage: that of the Cartes de Visite albums.

You know this Disderian invention, ma’am, it’s charming and absorbing! It has replaced autograph albums, potichomania and the succession of more or less absurd crazes that hit Paris every winter. This time, it’s clever and fun – and very expensive too, because the sun works at a fixed price and charges as much for the face of a Majesty as for that of an actress from the Bouffes-Parisiens: thirty soldes a piece. I saw twenty women busy forming collections that will be one of the amusements of the small evening gatherings this winter. The prodigal women go to buy their albums in the rue de la Paix, and thus pay twice the factory price. We see them sitting on Maquet, Giroud or in the passageway of the Opera, choosing their cards, – and looking especially at the ones… that they don’t dare to buy. In the evenings, they have fun sliding them into the slots in the album, and discuss the two systems at hand, which consist of: one writing the names under the portraits, – the other not putting anything. […]

Another anxiety of the first collectors destined to set the general tone for the winter: one must proceed by categories, classifications, specialties, – or else make the collection a salad, a carnival, a mess! […]

So, ma’am, it’s one of the emerging rages of the moment, the guaranteed vogue of the coming winter, and this time it’s an intelligent, spicy and fruitful diversion.

To clarify, autograph albums were notebooks in which friends were asked to write a thought or dedication and sign it. Potichomania was a type of handicraft made from bottles with collages and paint on the inside. These were two fashions that passed.

What’s interesting is the way he describes the Cartes de Visite as a craze, something that everyone is talking about. The collections that were formed were not restricted to friends and family, but the CDVs of celebrities were much sought after. These were usually even sought after by photographers, as they could then sell the copies on the vigorous market that had formed. In some cases it worked as publicity for the subject and they were happy to have their copies for free, for example. But in other cases there was a contract defining the rights and obligations of each party, depending on whether they felt inclined to give in or demand. This happened when a good financial return was expected.

Regarding the two systems that Jules Lacomte mentions, whether or not to put names under the portraits, and whether or not to group them by categories of characters, he is in favor of not putting names because it makes the discussion between friends more lively with people trying to guess or wanting to show off their familiarity with the celebrities in question. He gives a huge list but I’ve cut it down so as not to make it too long. For example, he mentions how much fun it would be to have Pope Pius IX and Giuseppe Garibaldi, two mortal enemies, together, since Garibaldi was fighting for the unification of Italy, which meant taking land from the Church.

This break with the idea of classes and hierarchies, when Jules Lacomte advises albums mixing characters at random, goes beyond his personal taste, it is more a manifestation, conscious or unconscious, of the Enlightenment ideals to which photography adhered so well. As he mentions above, CDVs had the same price, the sun charges the same for a queen or any other person, CDVs have the same format and appearance for everyone, they show people as they really are, in other words, there was an egalitarian sense to it all. Photography was democratic par excellence.

In order to grasp the importance that photography gained with the Cartes de Visite, people were known, even famous people, only by their names. This press of social and political events began around 1600 in Europe. But it was all text. There was a lot of talk about the greats of each era, but nobody saw them. Until the 1840s, the only faces we knew were those of the monarch on coins, a few political posters, usually satires, which only circulated in the big cities and a trade in engravings that only the wealthiest had access to.

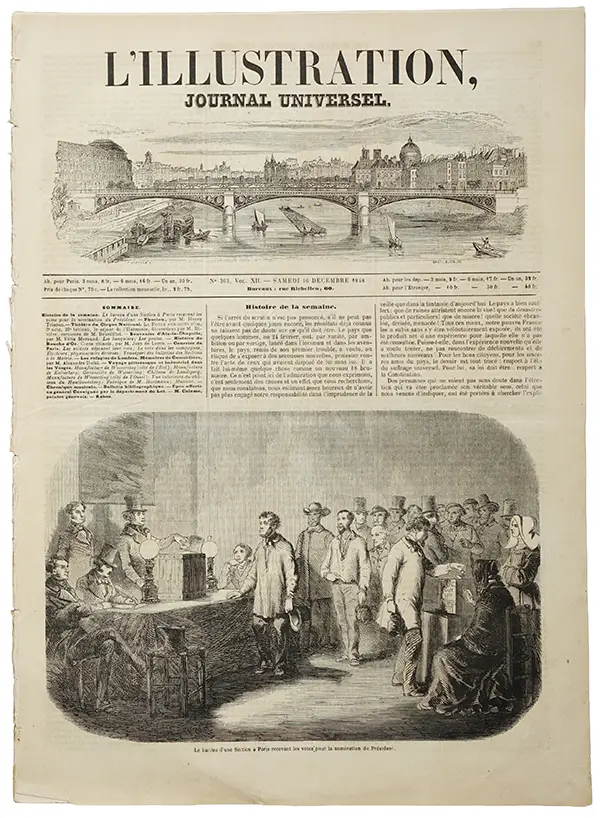

Copy of December 16, 1848

–

In 1842 the Illustrated London News was launched, and in 1843 L’Illustration, in Paris, which led a long line of periodicals, usually weeklies, with wood engravings and these were the first glimpse the general public had of the faces of those who were for some reason “important”. Politicians, artists, military, religious, bandits, all kinds of celebrities, for better or worse.

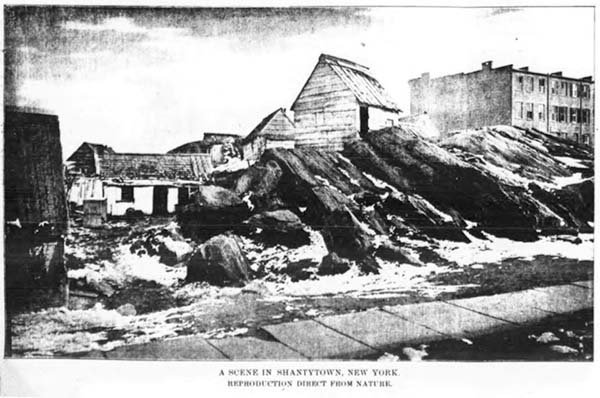

When photography appeared in 1839, the printing press was not yet able to reproduce it directly on its pages; the images were still copied by hand by an artist onto the wooden blocks of the prints. So the Cartes de Visite were the first process that effectively made people’s appearances, “printed by the sun”, without the intervention of an artist, circulate on a scale that we can consider massive.

Photomechanical processes for the press only appeared in 1880, pioneered by the New York Daily Graphic with the photo above. The caption reads: A scene in Shantytown, New Youk – Reproduction direct from nature. Until then, photos could only be seen on an original photographic support.

Why did people want so much to see themselves and each other in a photomechanical process? That’s a fascinating question, but for this article we’ll just stick with the fact that it was the Cartes de Visite that made it possible. Cartomania, which took hold in the 1860s using Disdéri’s invention, was a phenomenon that shook the whole world.

But we shouldn’t think that this was restricted to celebrity CDV collections. The most remarkable thing about this social phenomenon is precisely that with the CDVs the subject could see himself and his inner circle, in the same medium, format and even pose as the highest nobility. In the caricature above, from the 1865 series Les bons Bourgeois (the good bourgeois), Honoré Daumier ridicules the fashion for these pompous poses. In total contradiction to the portrait’s haughty expression, the caption reads “posing as a member of his region’s agricultural fair”. One of the examples Jules Lacomte gives of a funny juxtaposition to have in an album is the Shah of Persia on one side and an “opera rat” on the other, who would be a young ballet student at the Paris Opera. Only in the space of a Cartes de Visite album could these two characters find themselves in a situation of relative equality. With photography, people were experiencing these approaches for the first time.

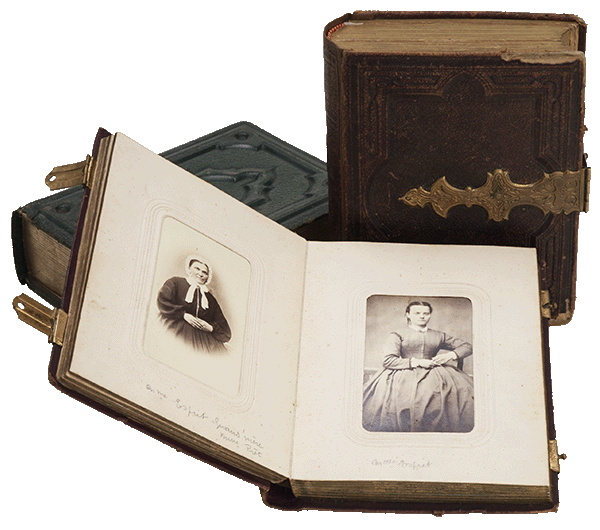

Collection Visit Cards

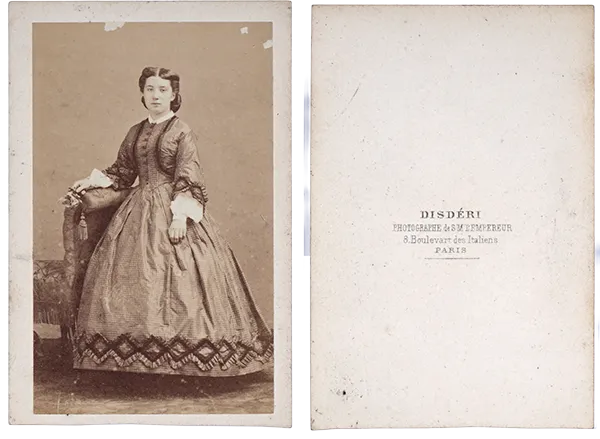

Below is a selection of Cartes de Visite with comments. They are shown side by side on both sides of the same piece.

To open, one of Disdéri himself, creator of the Carte de Visite. Note that he places his mark very discreetly but introduces himself as: ‘Photographer to His Majesty the Emperor’. This is because he made what must be his most famous CDV featuring Napoleon III.

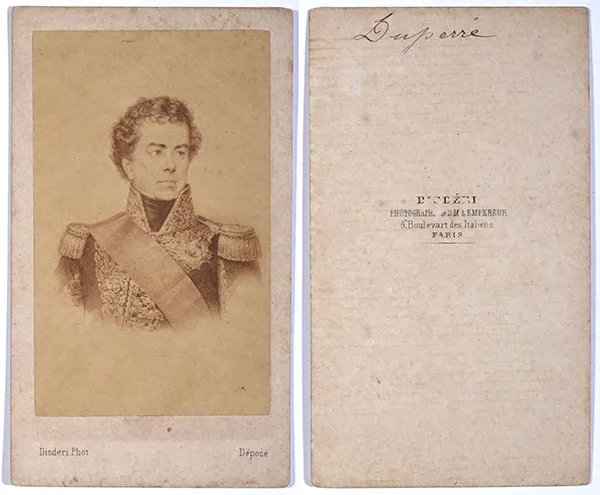

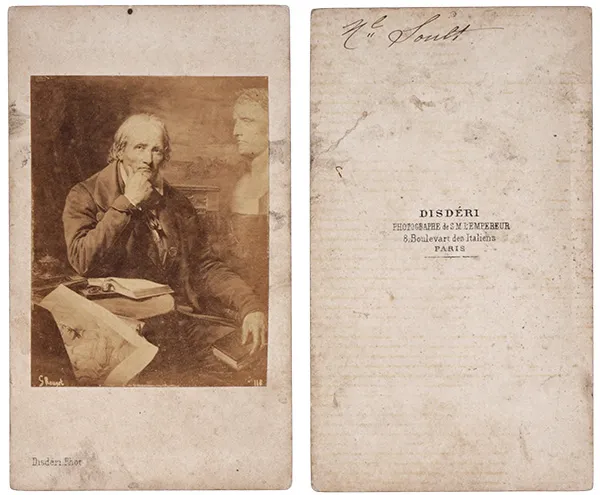

Another two by Disdéri. The interesting thing here is that he made CDVs from paintings. It was probably to take advantage of the trend for celebrity collections. Both are military, and in times of so many wars, this was certainly a highly collectible theme.

The first is Amiral Guy-Victor Duperré, who was Minister of the Navy and died in 1846.

The second is Jean-de-Dieu Soult, one of Napoleon’s most famous marshals and later Prime Minister of France, who died in 1851.

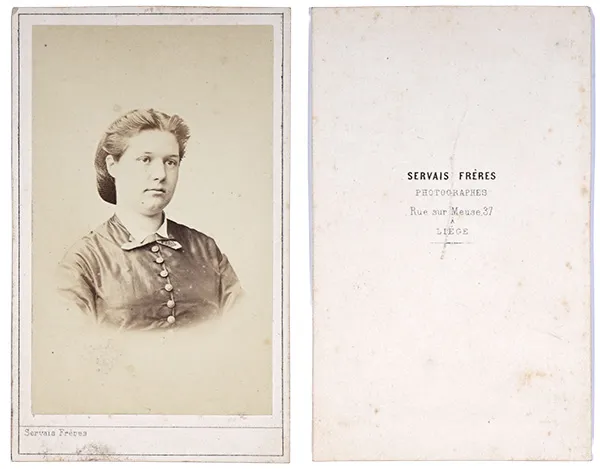

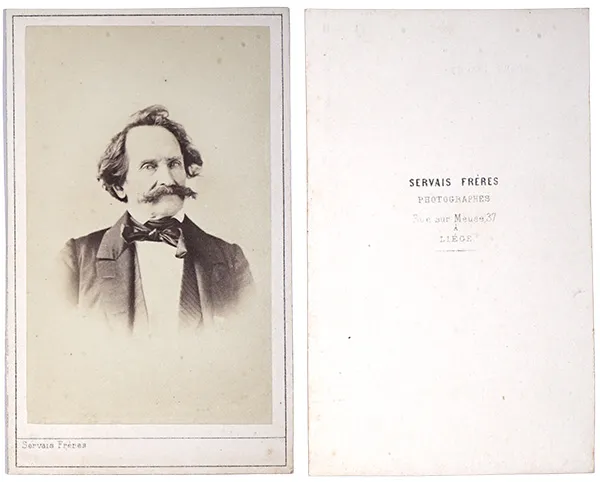

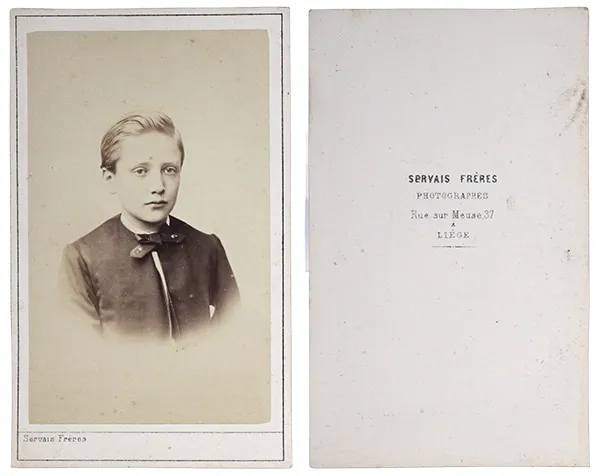

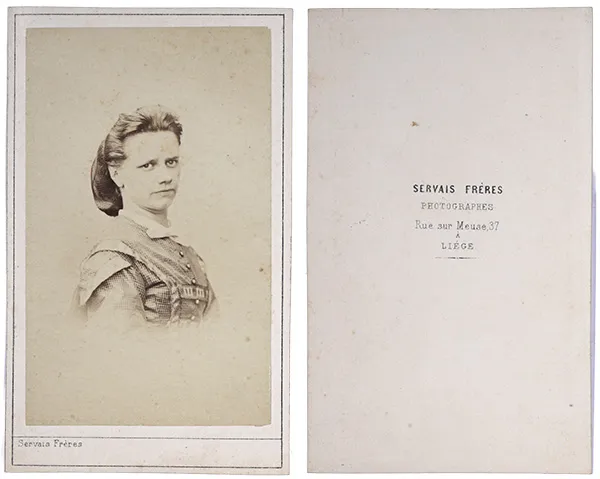

This was a typical CDV studio in the country town of Liége. The brothers Joseph-Arnold Servais and Jean-Théodore Mathieu Servais only worked from 1864 to 1866, so it’s easy to date these cards to that period.

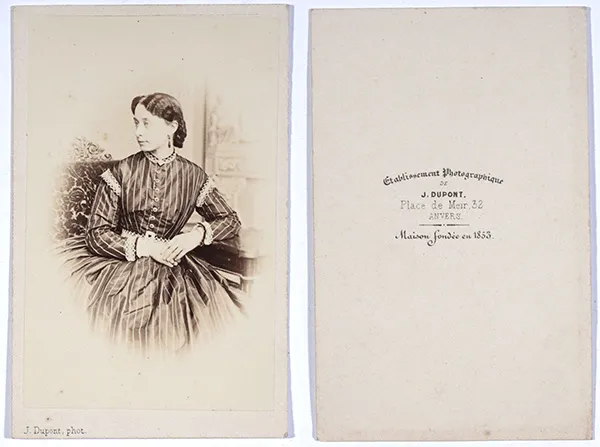

Joseph Dupont had one of the most prestigious studios in Antwerp. From 1866 he signed himself “Photographer to the King”, just like Disdéri. Compare the clothes and attitude of this lady with the portraits of the Servais brothers and you can see that they are very different clients. Joseph Dupont was a collaborator of the famous painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema.Henri Louis Aimé Dupont

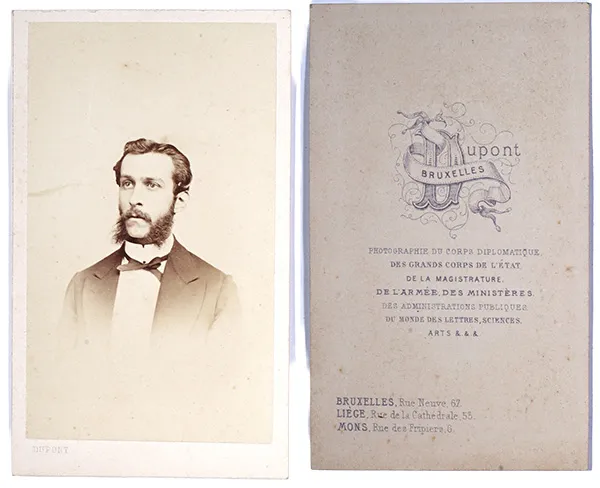

Henri Louis Aimé Dupont was the Disdéri of Brussels. Take a look at his list of clients: photographer to the diplomatic corps, high-ranking government officials, the judiciary, ministers of the armed forces, the public administration, the world of letters, science, the arts, etc, etc.

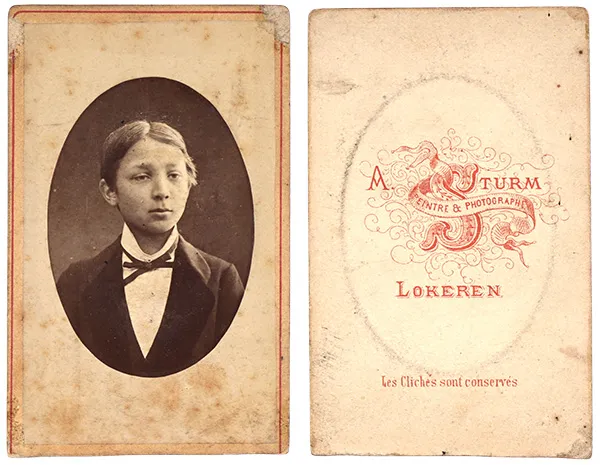

François Athanase Sturm presents himself as both a painter and a photographer. This was very common in the early decades of photography. Many painters migrated or more often combined the two. Sturm worked in photography from 1865 to 1895, a long career. But this CDV must be from after 1880 because the printing method is carbon, which is superior to albumen because it is more permanent.

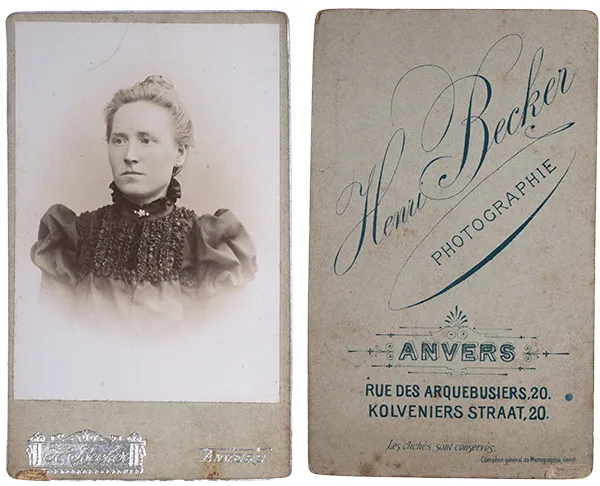

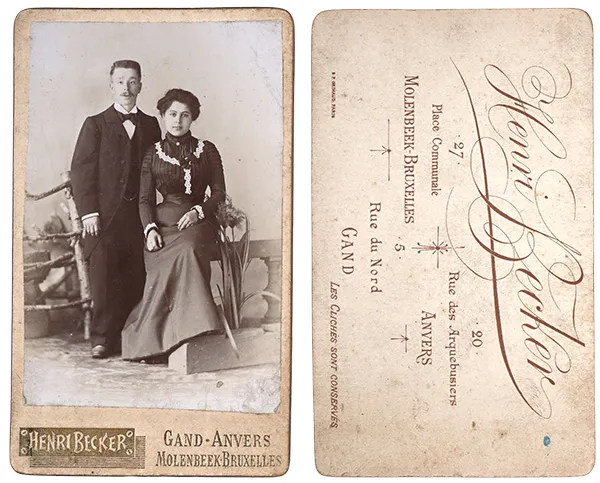

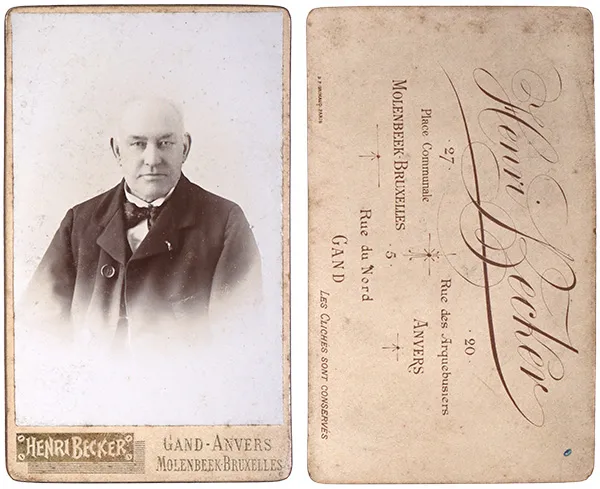

Many of the photographers in portrait studios were solo artists. But Henri Becker, active in a late phase of CDV, around 1900, was more of an entrepreneur who opened one of the first studio/shop chains in Belgium. They were run by his relatives and already used silver gelatine instead of collodion/albumin for both negatives and final prints.

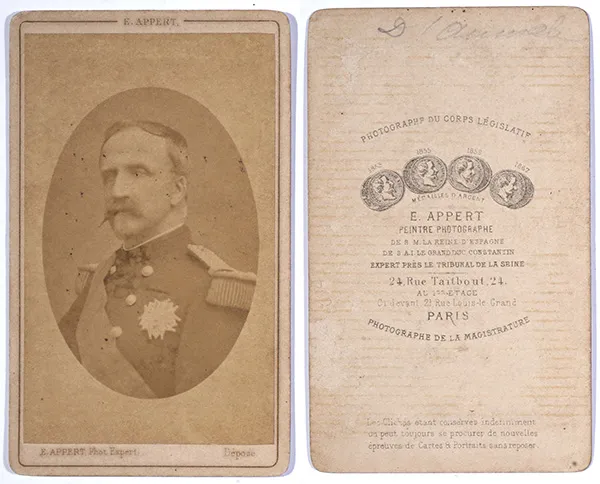

E. Appert could be Eugène or Ernest Appert, two brothers, Eugène being the more active. He presents himself as Photographer to the Judiciary and Photographer to the Legislative Body. He is considered a pioneer in judicial photography. Interestingly, he photographed both criminals and the political elite of his time. He is famous for having, during the Paris Commune, when he was against the communards, published photomontages with fake executions of commune activists.

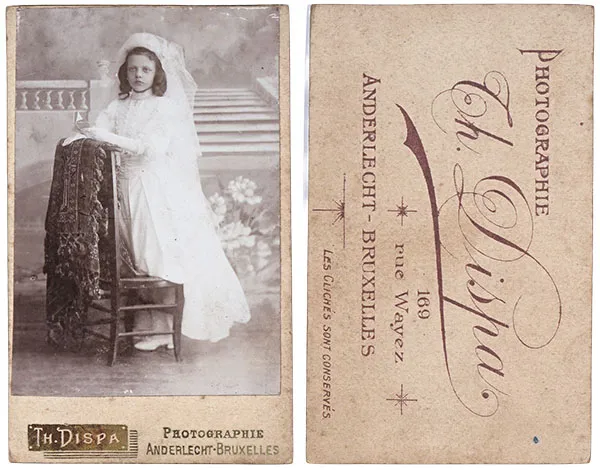

Théodore Dispa was a stepson of Henri Becker. As we have seen, the family ran a successful network of photographic studios in Belgium. They catered for a middle-class clientele in a period that was already late for Cartes de Visite. This is a typical first communion photo printed on silver gelatine paper.

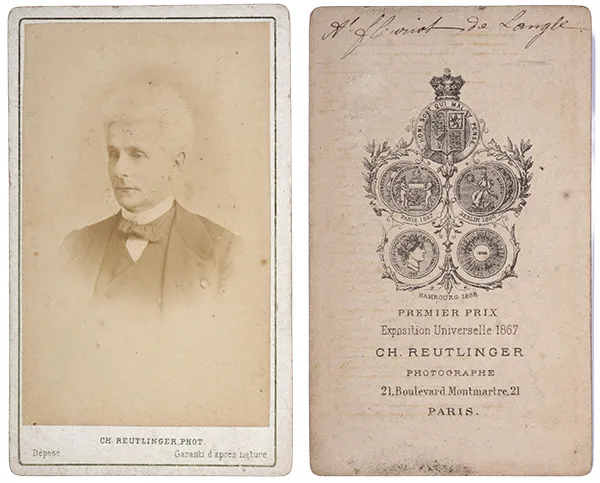

This is a CDV dating from 1868-1875. The printing process is traditional albumen. You can tell by the coloring and fading. Reutlinger was one of the leading studios in Paris at this time, rivaling Nadar. The portraitist, you can read at the top of the back of the card, was Viscount Alphonse Fleuriot de Langle. It’s interesting to note that the front reads “garanti d’après nature”, i.e. a guarantee that the Viscount himself posed for the photo and that it wasn’t a photo based on a painting or drawing. This can only be due to the fact that this is a print for sale to celebrity collectors, as the Viscount himself wouldn’t have needed this comment. Reutlinger was a photographer of high society, actors and opera singers.

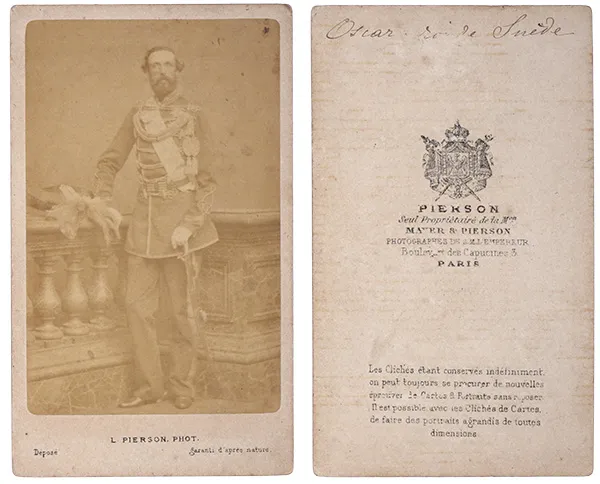

Another very important Parisian studio, and for various reasons. Pierson produced around 400 highly sought-after portraits of the Countess of Castiglione, a beauty of the time. He was (like Disdéri) photographer to Emperor Napoleon III. He won a case that established jurisprudence for copyright on photographs. The date of this CDV can be placed between 1878 and 1880 and in it we have King Oscar II of Sweden and Norway

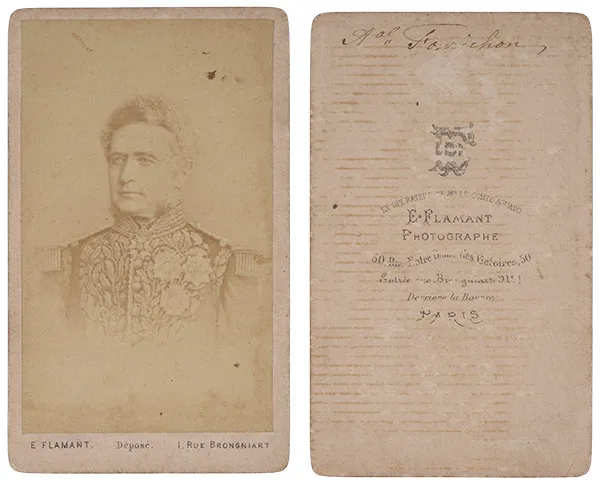

E. Flamant, from Paris, uses as a credential: Ex Opérateur de Mr LE COMTE AGUADO, the Count of Aguado is an important figure because although he was not a commercial photographer, not least because he was very wealthy, he was one of the founders of the Société Française de Photographie and contributed to various developments in photographic technique. The date of this CDV must be around 1870, as it features Léon Martin Fourichon, Vice-Admiral in the Navy. Certainly a collectible card in its day.

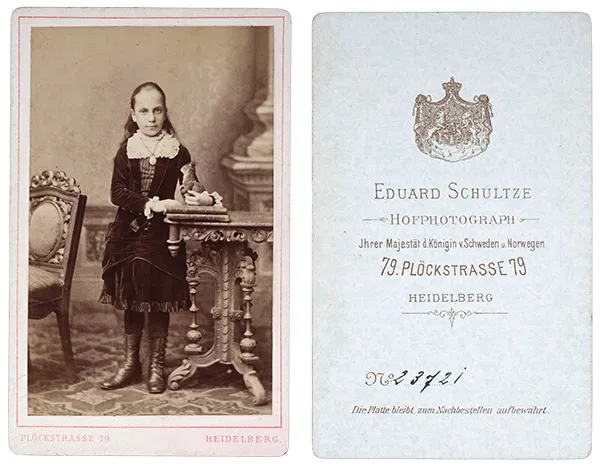

Edward Schultze was a leading photographer in Heildelberg. He uses as a credential being the photographer of the Queen of Sweden and Norway, who at the time was Sophia of Nassau. Sophia was German and was probably photographed on a visit to Heidelberg and authorized Schultze to use the reference. The date of this CDV is probably between 1872 and 1875.

The curious thing about this picture is that the girl seems to be posing for the photo with a live rabbit. You can see that the rabbit’s ears have moved during the exposure, which must have taken a few seconds.

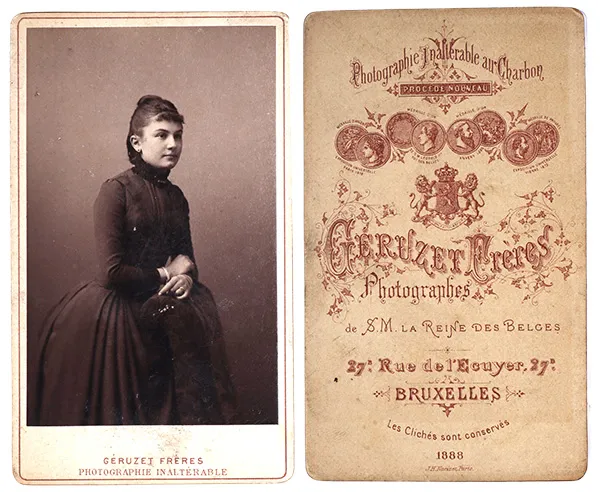

This was one of the most prestigious studios in Belgium. The Geruzet brothers, Alfred and Jules Geruzet, presented themselves as photographers for Her Majesty the Queen of the Belgians, who at the time was Marie-Henriette, wife of King Leopold II. The book Studios of Europe states that they only used charcoal as a printing process because of its permanence and overall quality, which was far superior to albumen. The top of the card reads: Photographie inalterable au charbon, where charbon is precisely the carbon pigment. In Portuguese we say carbon print. Considering that this is a CDV from 1888, we can see that it still retains a very wide tonal range, going from deep blacks on the dress to very light tones on the face of the portrait.

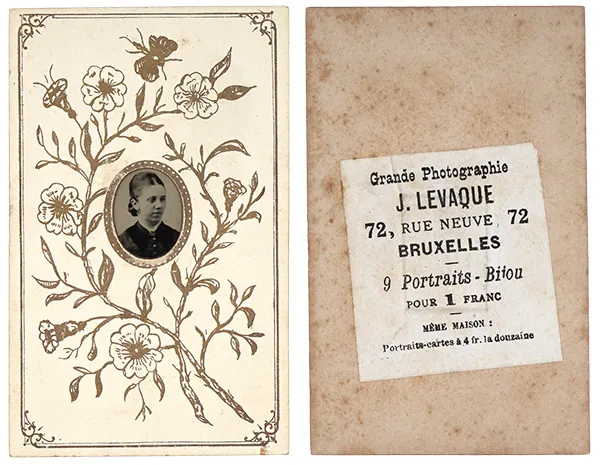

Here’s an economical solution from the Grande Photographe J. Levaque in Brussels. It’s a ferrotype, a direct printing process on metal using collodion. He offered 9 “bijou” portraits for 1 franc. It used a camera that produced the nine portraits on a single plate because it had 9 small lenses on the front panel. The exposure was around 10 seconds. Ferrotypes were widely used to make medallions, brooches and the like. In this case, it was framed by a card in the Cartes de Visite format. But it’s another product. We see that a dozen traditional CDVs, in albumin, cost 4 francs.

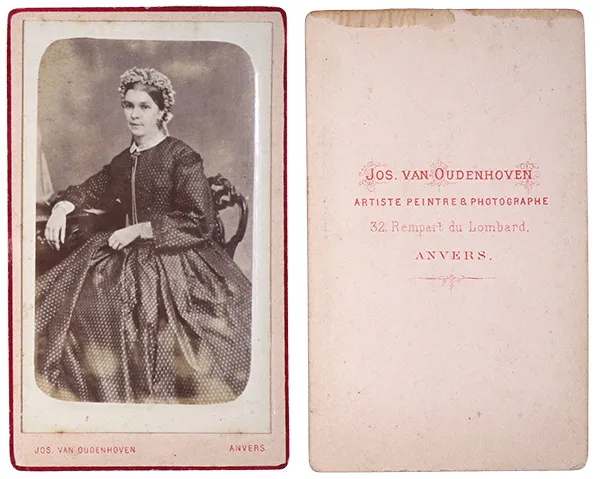

This is a typical Carte de Visite from the early 1860s. The portrait’s dress, which was fashionable between 1860 and 1866, already gives away the date. But if we look more closely at the photograph, we can see the red thread on the edge, the sharper corners and, above all, the fact that Joseph Van Oudenhoven introduced himself as an “artist painter and photographer”. It was very common for people with a background in the arts to choose photography as a profession, as demand was very high and the talent of an artist painter could be very useful not only for directly retouching or coloring photographs, but also for refining the lighting and composition of the photo.

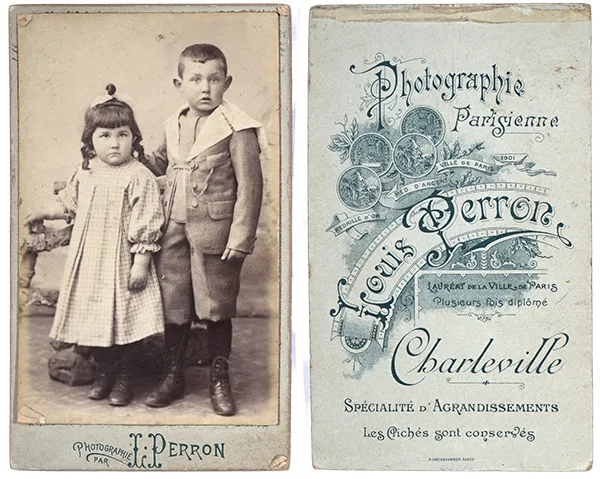

This is an interesting example, starting with the children’s expression, perhaps somewhere between fear and curiosity, but the fact remains that Louis Ambroise Perron was a special kind of traveling photographer. Note that there is no address on the card. He was from Charleville, but he traveled around France with his “Photographie Parisienne”, an attractive title for those who lived in the countryside and couldn’t have themselves portrayed by one of the famous Parisian studios. His work is late, between 1894 and 1897 was his itinerant period to which this CDV probably belongs, from 1898 to 1906 he settled in his hometown. He wasn’t famous, but he was a successful photographer. His son Lucien Perron continued with the studio in Charleville for many years.

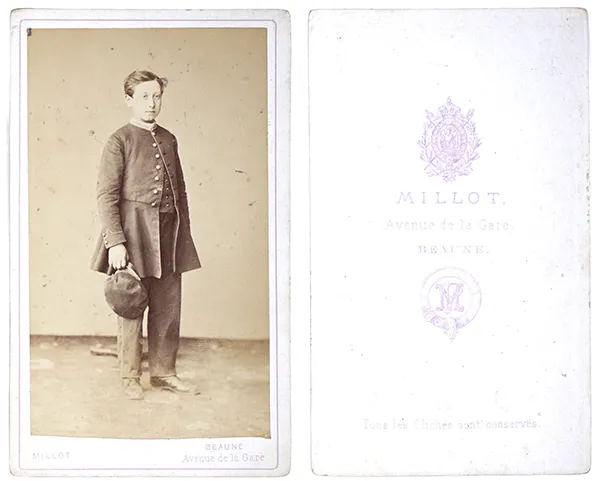

This Carte de Visite illustrates the attraction that photography had for people from the most diverse backgrounds. Before becoming a photographer by profession, Nicolas Zacharie Millot was an academic, teaching mathematics, physics and drawing. Due to his fine education, he also contributed to studies in history and archaeology. He was active as a photographer from 1879 to 1889. Regarding the boy in the photo, perhaps it has something to do with Millot’s academic life, as he is in student uniform. He must not have come from a very wealthy family, as we can see from the state of his clothes and especially his shoes, which look worn.

Carte Cabinet

In 1866 the London photographer F.R. Window introduced a new format called Carte Cabinet. It was the same set-up, a photo on thin paper glued to a card with the brand and information about the photographer. But the size was 11 x 17cm, so much bigger.

While Carte de Visite were more for albums and collections, Carte Cabinet were more for family memories and were displayed individually. The name Cabinet comes from the fact that it’s the perfect size to stand on a shelf.

A very common device that appeared with the Carte Cabinet was the Graphoscope. It’s basically a magnifying glass and a stand that greatly improves the experience of examining photos as it fills the field of view. Some graphoscopes also had a pair of lenses for stereoscopic observation, as you can see in the photo above.

As early as 1870, it became the preferred format for portraits other than for albums. Its use continued until the beginning of the 20th century. This is why Cartes Cabinet kept pace with changes in printing methods. There are Cabinet Cards in albumin, carbon and many in silver gelatin paper.

Below are some Cabinet Cards from the collection. In order to maintain a size relationship with the previous Cartes de Visite, I chose to place the front on top of, rather than next to, the back.

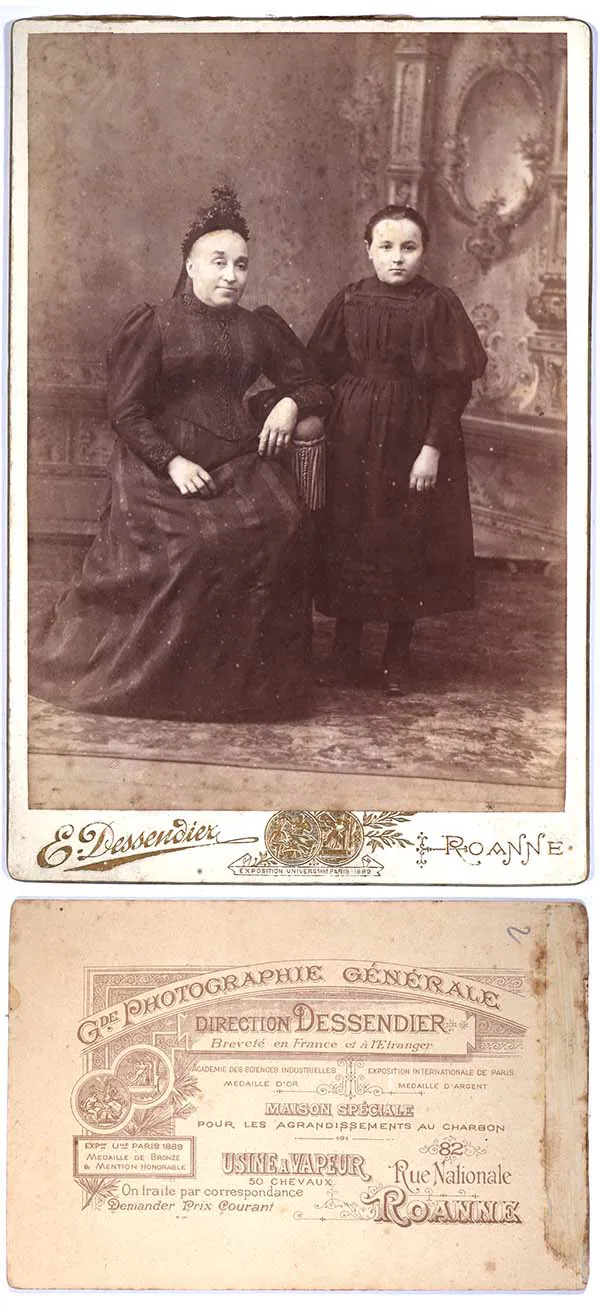

This Carte Cabinet is an excellent example of the industrialization of photography at the end of the 19th century. The 50-horsepower Usine a Vapeur, which is proudly displayed on the back of the card, means that Dessendier had a voltaic arc to generate light and no longer relied on natural lighting to print his photos. He worked by post and specialized in carbon enlargements. It was very common at the time for Cartes de Visite to be sent for enlargement and this meant a good source of extra income for the studios.

As for the subjects, they appear to be mother and daughter and are in strict mourning. The signs are the fabric of the dresses, which are not shiny satin or silk, the absence of jewelry and, above all, the adornment on the lady’s head, which was typical of the first stage of mourning.

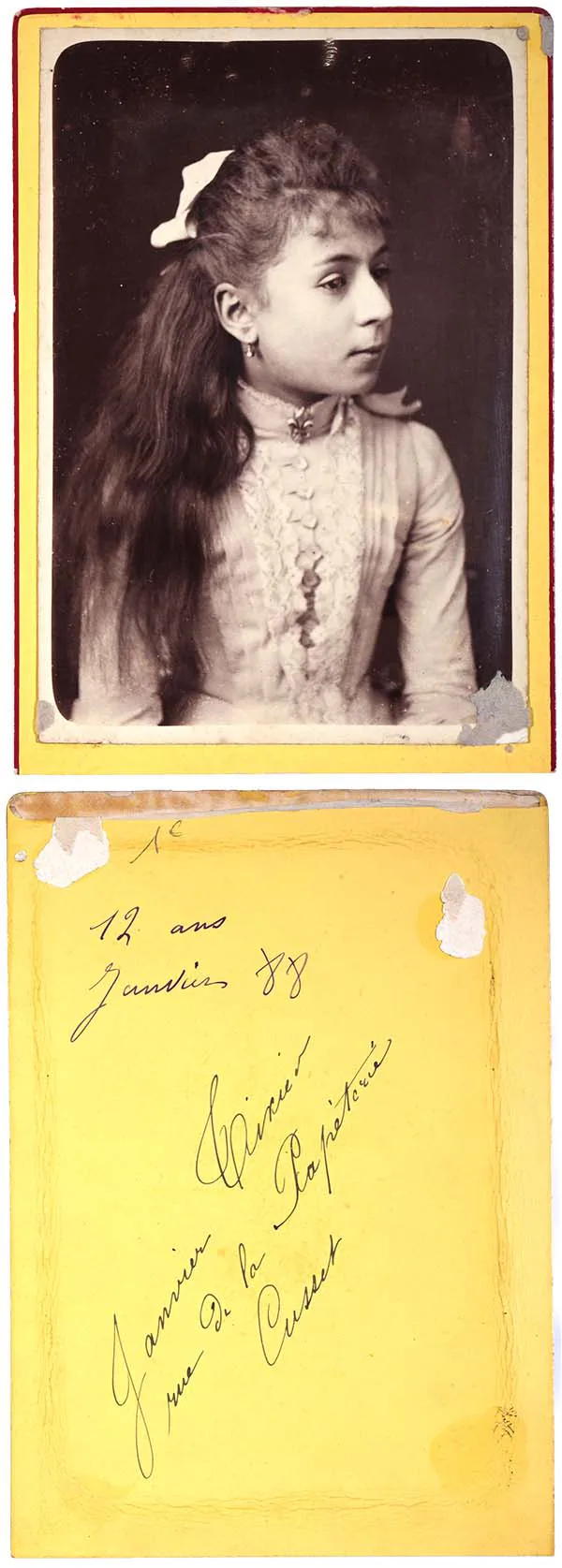

This is a Carte Cabinet dated January 1888. The photographer did not, as usual, use a printed card but handwrote his name, Vivier, his address Rue de la Papeterie and the town Cusset, which is in central France. Photographers in these small towns often bought blank cards and proceeded in this way. Probably as a cost-cutting measure.

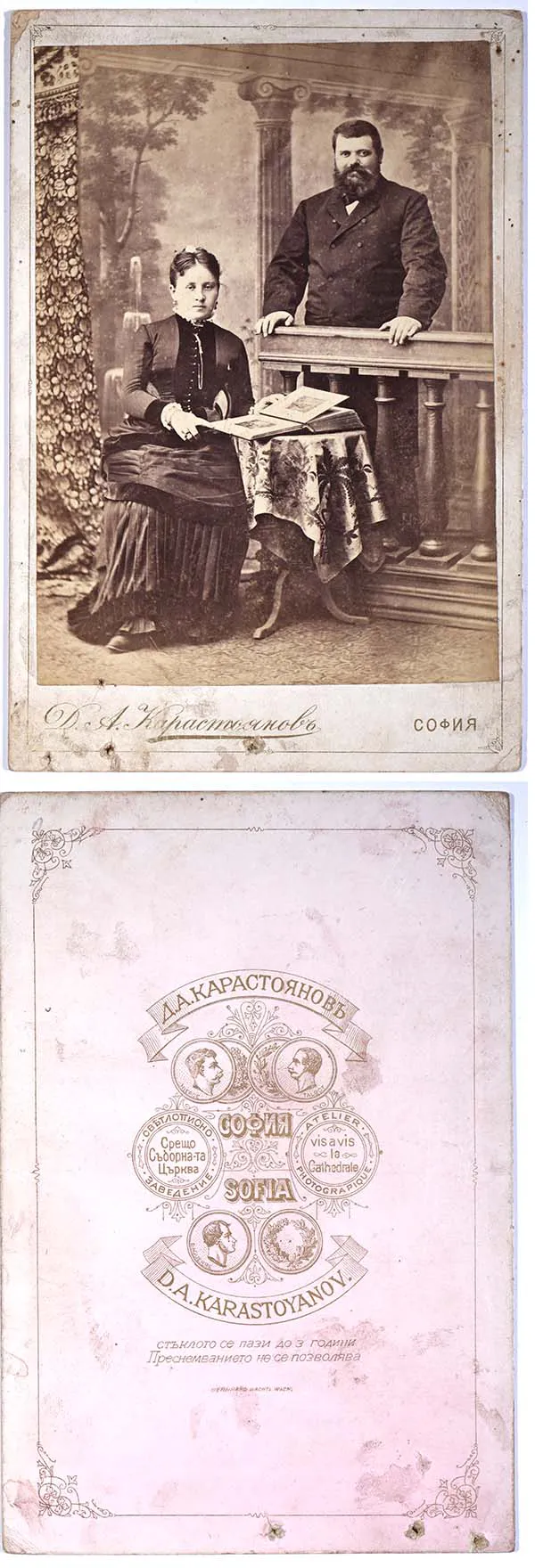

Dimitar Karastoyanov belonged to a real dynasty of photographers. The son of Anastas Karastoyanov, who is considered the father of photography in Bulgaria, they were also printers and played an important role in politics. His studio was in the most prestigious spot in Sofia, right opposite the cathedral.

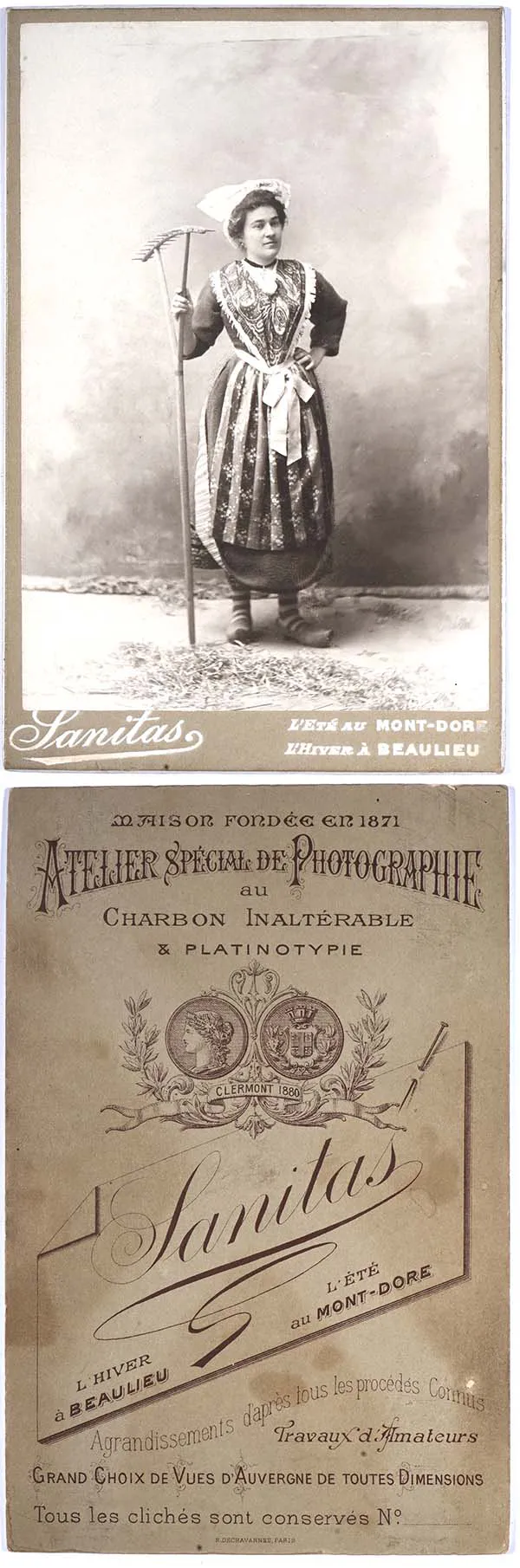

This is a good example of one style of Carte Cabinet: the folkloric tourist photo. Mont-Dore was and still is a thermal spa in the Auvergne region of France. The photographer Sanitas writes that he stays in Mont Dore in the summer and in Beaulieu in the winter. It was a strategy to keep up with his clientele. It was an advanced studio because it offered enlargements in carbon and also in platinotype, the most sophisticated processes. As for the photo, the tourists who frequented the spa liked to have images of local characters in traditional clothing. This could be a Carte Cabinet made with a model and bought ready-made, but it could also be a characterization of the client who wanted to represent herself as a local.

Conclusion

The Cartes de Visite were an extension and expansion of something that the daguerreotype, due to its one-piece nature, materials and cost, could not offer. With them there was a first movement towards the capillarization of photography. It still remained basically a professional practice. The “photographing” gesture remained very much restricted to these professionals or a few very dedicated amateurs. But getting to know and experience photography, collecting and having oneself photographed, reached what we can safely call the general public.

As an iconography, I think we can say that this object in which monarchs and workers coexisted was a magnifying glass that gave tangible support to abstract ideals of equality and rights drawn by the great and impartial light of the sun. Society was able to examine everything and everyone in the same showcase, from the same point of view, in the same album.

This is how photography played an instrumental role in solidifying the concepts launched by the Enlightenment. It was received as a kind of concrete proof that people could finally be equal.