Ambrotype | James Ambrose Cutting

The ambrotype is just a special application of Frederick Scott Archer’s collodion. At first, Archer thought of it primarily as a process for obtaining negatives on glass. He was aware of the possibility of making positives, but this was not his intention. It may seem strange that the same process can be used to make positives and negatives, but there is a logical explanation for this.

The process itself is essentially the same as for negatives, the way the salted collodion is applied to the glass, sensitized, exposed and developed. See the article on wet plates. However, some variations improve its appearance when the process is aimed at a positive.

We can say that in our eyes a gray when placed against a white background plays the role of a dark tone. When placed against a black background, the same gray, plays the role of a light tone. Taking advantage of this fact of our perception, the idea of the ambrotype was to place a black background behind what would be a negative.

This works because the high lights in a negative represent the largest silver deposits. These deposits are not absolute light absorbers, they reflect a certain amount. Remember that, when used as a negative, the point is not whether they reflect or not but whether they transmit or not, because in the negative they must prevent light from passing through. This can be done either by absorbing or reflecting the light that falls on them.

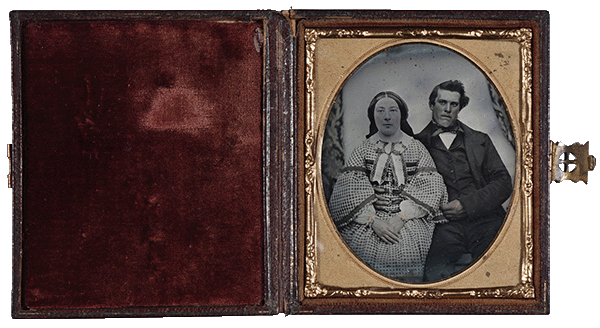

Look at the ambrotype of this couple. Everything that is white or light is diffusely reflecting the light it receives. In these areas we have the silver layer that has been sensitized and developed. Everything that is dark is not reflecting the light that falls on these areas, it is allowing us to see through the glass. But what do we see? We see the black background that was placed there because the glass was painted on the back with a black varnish, or a black velvet was placed behind the glass. More rarely, very dark glass was used, usually ruby-colored.

To improve the effect, two techniques intensified the contrast in the ambrotype:

1- It was deliberately underexposed compared to what it would have been for a negative. This made the shadows more washed out, more empty and the black of the background appeared with greater depth. Any layer, however slight, of silver would make the area more prone to reflecting light and this was avoided by underexposing.

2- The developers were less energetic, slower, and this tended to produce a smaller grain, a finer deposit that reflected the light better.

With these small variations it was possible to obtain very detailed images without that mirror effect that is inevitable in daguerreotypes and gives us the feeling that we are looking at the wrong angle.

Because of these characteristics, ambrotypes were considered nobler modes within the photographic possibilities of the time and deserved the same richly ornamented cases that had previously only been used for daguerreotypes.

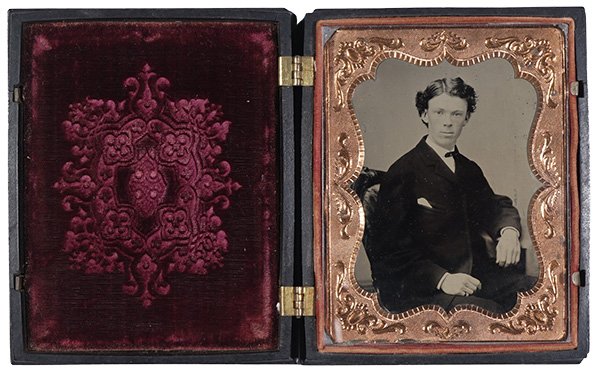

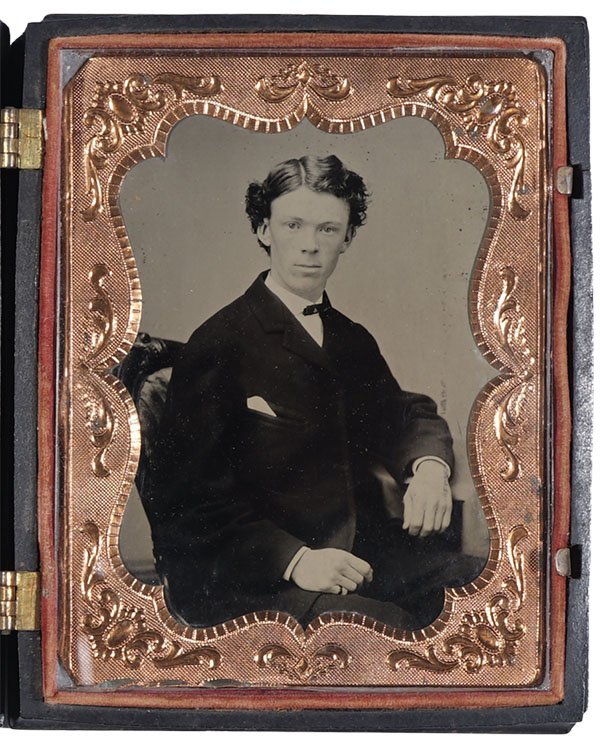

The ambrotype above, featuring this young man with a very firm and assured gaze, came packaged in a finely finished gutta-percha case. The lid has a bas-relief depicting the scene from a well-known story called the “Falconer’s Bounty”. A nobleman loses his falcon during a hunt, but a peasant girl finds the precious animal and returns it to its owner. We see the boy on his horse offering a cash reward for the lady’s good deed. Is there a connection between the boy in the picture and falconry? Perhaps he chose a theme linked to generosity? It’s impossible to know.

Gutta-percha is a natural thermoplastic that comes from the tree of the same name. Many boxes were stamped with genre scenes like this one, with a moral background, scenes from the Bible and allegories representing faith, hope, charity and other values that perhaps related to the people being photographed. But in the absence of references, we can only speculate.

The name ambrotype comes from a patent by James Ambrose Cutting, filed in 1854 in the United States. But his contribution was not so much to the process itself as to the stage of obtaining the image, which was, as we have seen, practically the collodion negative process. What he added was the idea of sealing the image by applying Canada balsam over the image and a second glass on top. This protects the image physically and chemically.

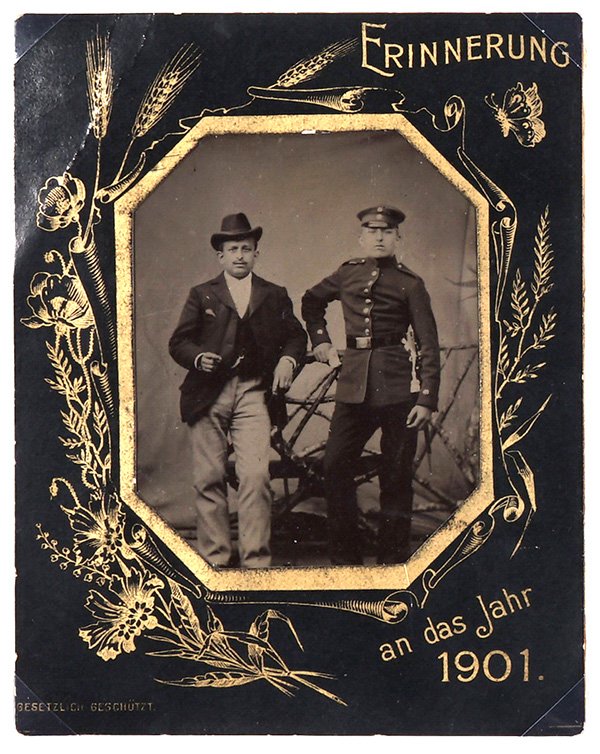

Until 1865, the ambrotype was one of the main photographic processes. It rivaled the collodion negative printed on albumen paper, which was much more popular and allowed for the Cartes de Visite. Its direct rival, which also used collodion, was the ferrotype or tintype, which is very similar but simpler and cheaper, hence the Abrotype quickly lost ground in the public’s preferences.

If you are in the Photographic Processes theme circuit:

The direct positive process of the ambrotype would have enormous appeal for itinerant photographers who set up their tripods in streets, squares, popular festivals, or any other gathering of people and could sell a picture right away. However, it was was too expensive for that kind of business. In the next room, you will meet its poor cousin, the ferrotype, which uses the same process, but with a trick to achieve a very affordable price.