The daguerreotype

The daguerreotype was a photographic process that had enormous importance and a short life. Many researchers, more or less prepared, had been wondering and experimenting since the beginning of the 19th century how it would be possible to record the image of the camera obscura on some flat support. The Frenchman Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (1765 – 1833) achieved what is considered to be the first success in this direction with a view from the window of his house in 1827, known as Point de vue du Gras.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce – 1827 – view from his window, Point de vue du Gras

–

In the last years of his life, from 1829 until his death in 1833, he collaborated with another Frenchman, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, in search of a better method, since his method required many hours of exposure.

Daguerre continued his research and at the end of the 1830s he succeeded with the process that became known as the daguerreotype. In essence, the process is very different from what he had discussed with Niépce. However, there is a controversy about the extent to which he was the sole author of the invention or the extent to which it was a usurpation to call the process by his name alone. The story itself is very interesting. It would yield a nice novel or feature film. For more details about their cooperation you can read, in the Studiolo, the article Niépce, Daguerre and the invention of photography.

From the beginning of his research, Niépce had in mind that photography would resemble metal engraving. For this reason, he was more inclined to use metal as a support for his pictures. Point de vue du Gras was made with bitumen from Judea applied to a tin plate.

Daguerre continued along these lines of using metals. Unlike, for example, others who researched ways of sensitizing paper, such as the Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot, who also succeeded in 1841.

What everyone already knew was that silver forms salts that darken when exposed to light. So silver was a kind of common denominator in many attempts to invent photography.

Daguerre experimented with silver-coated copper plates and the process in which he finally succeeded was officially presented to the world in 1839 with the following procedure.

The daguerreotype of 1839

1- A copper plate is coated with silver. In Daguerre’s time, this was done mechanically. First, a block of copper was heated with a smaller block of silver on top of it until they were fused together. Then the two were successively passed between steel rollers until a thin sheet was obtained with one metal on each side. It wasn’t until the late 1840s that electroplating processes, using electricity, were introduced and greatly facilitated this stage.

2- Next, the silver face was polished until it looked like a mirror. All the literature of the time is very insistent on the quality of this polishing as being an essential factor in the success of the daguerreotype. Much emphasis is placed on the fact that the polishing must be done with a progression of abrasives up to a final stage with “rouge”, a very fine powder made of iron oxide with particles between 0.5 and 3 microns. If it were sandpaper, it would be 4000 to 8000 grit. Rouge is used by jewelers.

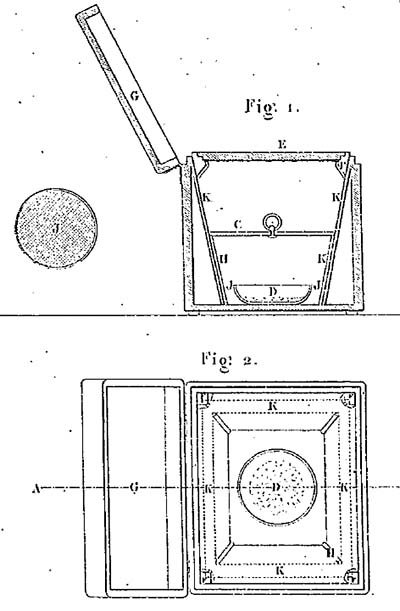

3- The polished plate is then placed in a box with solid iodine, which easily sublimates into a violet vapor. This vapor begins to deposit on the silver plate and forms silver iodide, which is a salt that is sensitive to light. The photographer observes the changes in the color of the plate in order to observe the layer deposit, which indicates when to stop the process.

Box for iodine. The granules are placed in the bottom D

and the plate to be sensitized on the roof of the box next to its lid.

This and the following illustrations are from the book “Historique et description des

procédés du daguerréotype […]”, from 1839, written by Lerebours, opticien.

–

The approximate colors that the silver surface will go through over the course of a few minutes are shown below. The photographer should inspect the evolution with a very dim light, usually from a candle, as it is at this point that the plate passes into a phase in which it is already sensitive to light.

The colors weren’t really as defined as you see on the screen. They were fleeting because they were a metallic reflection and an iridescence like you see in oil stains or soap bubbles. But they can be roughly represented by the sequence below.

.color-swatch-container { display: flex; flex-wrap: wrap; gap: 15px; } .color-swatch { width: 100px; height: 100px; border: 1px solid #333; border-radius: 8px; } .swatch-label { text-align: center; font-family: sans-serif; font-size: 14px; margin-top: 5px; } /* Daguerreotype Fuming Colors */ .straw-yellow-sheen { background: radial-gradient(circle, #FFFADC, #FAF5D2, #D4CEAD); } .golden-yellow-sheen { background: radial-gradient(circle, #FFF8DC, #F0D264, #B89B3D); } .rose-violet-sheen { background: radial-gradient(circle, #FADADD, #C85AA0, #6A3056); } .blue-sheen { background: radial-gradient(circle, #D4D9E8, #4664B4, #2A3D6D); } .green-sheen { background: radial-gradient(circle, #E3E6DE, #8C966E, #5C6347); }Daguerre removed the plate at the very first stage when it was pale yellow. Later, when bromine was added as an accelerator, photographers would let it go as far as the violet stage. If it went beyond that, into blue or green, the effect was reversed and the plate would no longer be sensitive.

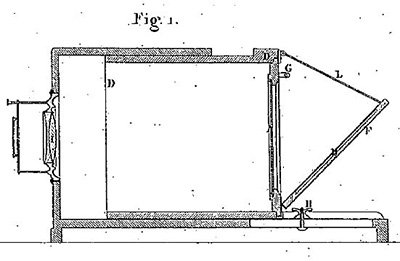

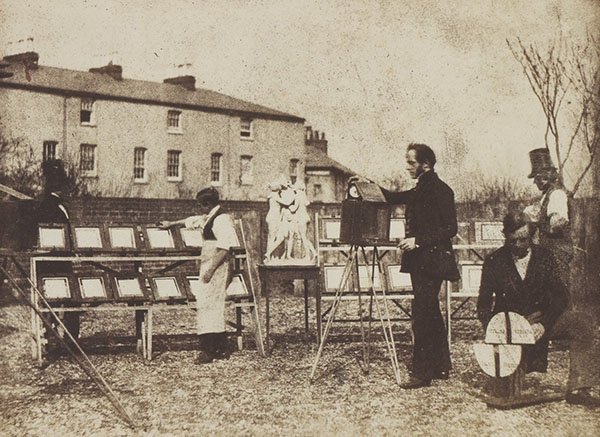

4- The next step was the exposure, which Daguerre made with a landscape lens manufactured by Charles Chevalier and offering f/15 or f/16 as the largest aperture. The exposure time varied from 3 to 15 minutes on clear days and depending on the subject.

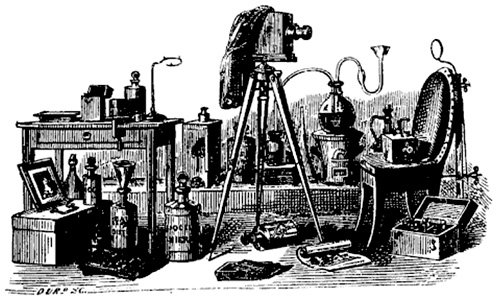

Typical camera for daguerreotypes, chambre a tiroir or

sliding box. Without bellows, there are two sliding boxes.

–

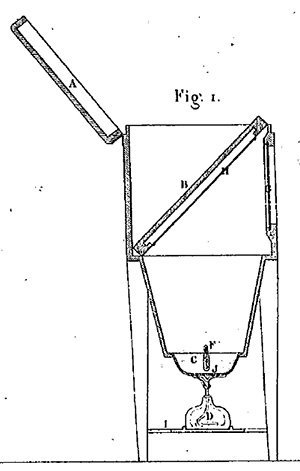

5- The plate was then taken to another steam bath, but this time with mercury, which is a liquid metal at room temperature. An inverted conical box was placed on top of the plate and a lamp heated the mercury at the pointed end below.

Mercury vapor bath box

–

The toxicity of mercury was known but not very well understood. Hat makers used it to make felt. Ailments such as tooth loss, tremors, memory loss and depression, which were associated with the profession of hatter, were also common among daguerreotypists.

Mercury formed an amalgam with the sensitized silver and this amalgam has a light color, thus forming the high lights of photography.

6- The next step was to remove from the plate all the silver that hadn’t combined with the mercury but was still there and would potentially render the image unusable when exposed to light. The best Daguerre could come up with for this task was a strong solution of table salt, sodium chloride. But it didn’t dissolve all the silver and the stability of the image was compromised.

In February 1939, just a month after Daguerre’s process was announced, without details, at the French Academy of Sciences, an Englishman, Sir John Herschel, who already knew the properties of sodium thiosulphate in dissolving silver salts, gave this invaluable information Fox Talbot, who was also working on a photographic process, but this time on paper, as mentioned above. Talbot shared the recommendation with his friend Biot, from the French academy, and Biot, on his turn, passed it along to Daguerre, who immediately tested and adopted sodium thiosulphate as a fixer for his images.

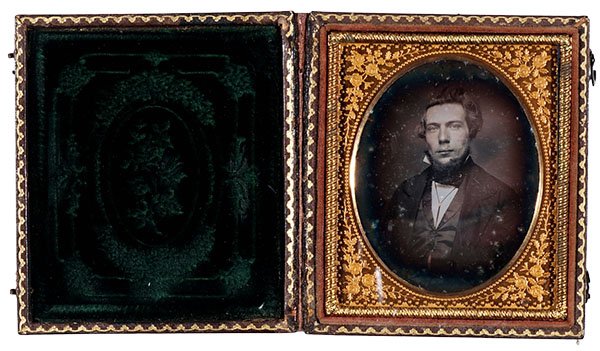

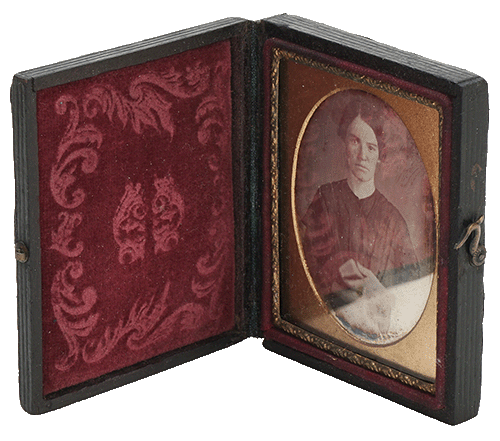

7- After developing the plate with mercury vapor and fixing it, the daguerreotype, in Daguerre’s original process, is washed and placed in a protective case with glass and a spacer so that nothing touches its delicate surface.

In 1840, another Frenchman, Hippolyte Fizeau, introduced a stage at the end of the process consisting of a gold chloride bath which improved the contrast, permanence and tonality of the daguerreotype.

The final product

Boulevard du Temple, Daguerreotype of 1838, by Daguerre himself. It was used to present the process at the Academy of Sciences in January 1839

–

What impresses most about daguerreotypes to this day is their wealth of detail. This is basically due to two factors. The first is that what we are looking at is the actual plate that was inside the camera. Every transition from one support to another, such as from negative to positive in the film process, implies more or less significant losses and in the case of the daguerreotype there are none because it is the first and only support. The second factor is the extremely flat and polished surface of the silver and the very thin sensitive layer that the steam baths create on it. Daguerreotypes really give the impression that the limiting factor is our own vision and not the resolution of the image itself. This aspect had enormous seductive power over people who had never experienced anything like that.

But it’s important to note that the photos we see of daguerreotypes, in books and online, are prepared in a way to show us the image at its best angle. This masks a characteristic that is very striking when we see a daguerreotype in person. Since a silver plate is polished into a mirror and the dark part, the shadows and blacks of the image are the part that has been taken off by the fixative, i.e. the part that has not received light, it is important for the observation of the daguerreotype that it is at an angle or in a position that reflects something dark. The dark parts are not really his, the daguerreotype’s, but what he is reflecting towards our eyes.

In the daguerreotype above you can see the mirror effect. The upper part, which reflects the dark cover, allows us to see the image clearly. In the lower part on the right, which reflects a white table, the image disappears due to the lack of dark tones.

–

When this doesn’t happen, what we see are the bright parts of the image that are light and the dark parts that are sometimes even lighter, because they are reflecting something light. You then have to find the ideal position to darken what should be dark.

To put it in more technical terms, the light parts reflect light diffusely, the dark parts specularly. This must be borne in mind.

The delicate surface of the daguerreotype meant that it had to be protected. Certainly as a successor to the small miniature portraits that were common until then, small frames with lids were created, cases that could be more stripped down or richly decorated. They undoubtedly contributed to the preciousness of the image being portrayed, especially in the case of portraits.

The short life of daguerreotypes came about with the emergence of other simpler, less expensive processes, with more sizes and reproducibility options. This was somewhat the case with Fox Talbot’s Calotype, but definitely with the advent of collodion glass plates for negatives and albumen paper for prints.

In the 1850s, in Europe, the migration to these new processes was very rapid and in the United States, until the 1860s, the studios still gave the inaugural process of photography a chance to survive, but after that it disappeared almost completely.

If you are in the Photographic Processes theme circuit:

Let’s go back to Talbot. Shortly after the announcement of the daguerreotype, he discovered how to make the negative for his salted paper from the image in the camera obscura. In the next room, we will see the calotype or talbotype process.