Wet Plate or Collodion | Frederick Scott Archer

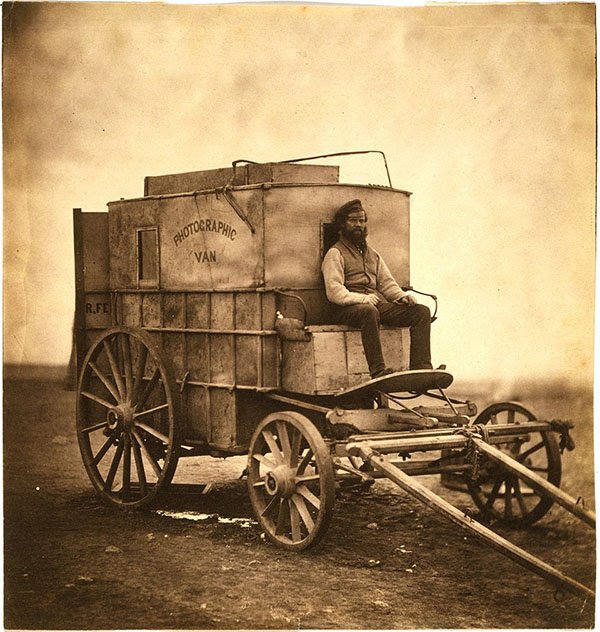

In order to make a wet plate, the photographer had to take with him the darkroom, in addition to the camera

–

The wet plate was developed by the Englishman Frederick Scott Archer and published in 1851. It is a process that, although very different, combines the best features of the daguerreotype and Talbot’s calotype. Like the Daguerreotype, it allows for an enormous wealth of detail, thus remedying the calotype’s weak point. On the other hand, like the calotype, it is a negative/positive process that allows countless prints to be made from the same negative. That is impossible with the daguerreotype because it is a direct positive, hence it is a single piece.

All of this is solved, as if by magic, because wet plate is a process that uses glass as a base. Of course, since it’s a negative, you have to print the final photo afterwards. But this was done without problems using paper with albumen, egg white, as a base for the silver salts.

On collodion, egg white and later gelatine, among other supports that have been experimented with, what is sought in them is that they have the following basic characteristics:

1- That they retain the silver salts in sufficient quantity and uniformity so that the image reaches a good density in the most illuminated areas of the scene, that is, that they block the passage of light in those areas according to areas of light and shadow.

2- That they allow light to penetrate, that they have transparency so that even crystals embedded, suspended, a little deeper in the support can receive light and thus become sensitized.

3- That allow the developer to reach these crystals, that are permeable to the developer and thus allow it to reveal as many crystals as possible that have been sensitized by the light.

Collodion is a kind of syrup and forms a relatively thick layer on the glass. It is a viscous and very volatile liquid, obtained by diluting nitrocellulose in ether and alcohol. It was only discovered in 1846 and so its use in photography was a very rapid discovery.

The big problem with collodion is that it needs to receive the silver salts, be exposed and developed while still damp. This forces the photographer, when working outdoors, to take not only his camera, plates, lenses, tripods, etc., which were already quite heavy, but also a complete darkroom to sensitize and process the plates on site.

Despite this enormous operational difficulty, collodion was adopted as the practically hegemonic process from its invention until the end of the 1870s, when the new plates, now dry, using gelatine as a base, replaced it.

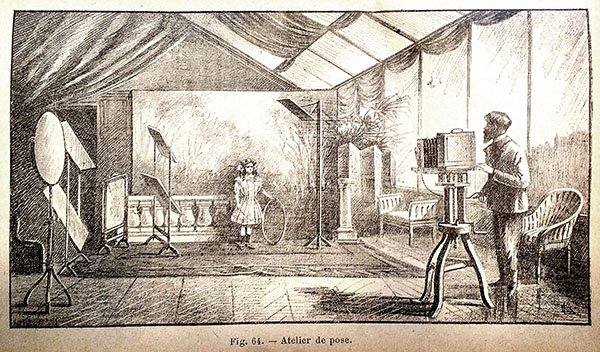

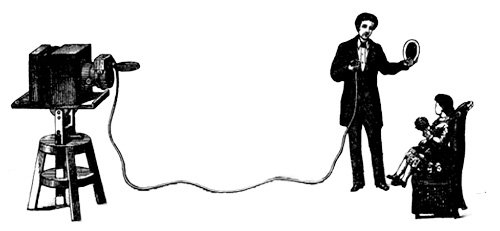

The great advantage of collodion, which made photographers willing to carry the lab with them, was that in addition to the advantages already mentioned, it was more sensitive than the processes known until then. For example, in a well-lit studio with a glass roof and large windows, like the one in the illustration above, using a Petzval lens at f/3.6 to f/4, a portrait could be made in between 3 and 15 seconds, a daguerreotype would require between 5 and 40 seconds, a calotype 1 to 3 minutes. An outdoor scene on a clear day, with f/22, between 1 and 5 seconds were enough. The collodion had an ISO equivalent to 0.5 to 3 and that was already wonderful.

This is the mobile laboratory in which English photographer Roger Fenton covered the Crimean War in 1855 using the latest technology: wet plates.

–

Process steps

1

Preparing the plate: A glass plate is meticulously cleaned (usually with alcohol and chalk/calcium carbonate) to make it chemically impeccable, as any dust or grease will cause visible flaws.

2

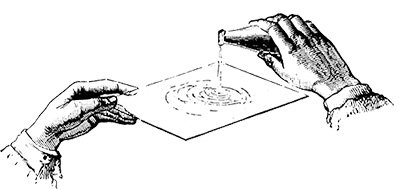

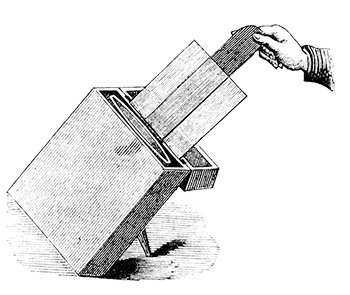

Applying the collodion: The viscous solution called “salted collodion” (nitrocellulose dissolved in ether and alcohol, containing iodide and bromide salts) is poured into the center of the glass. The plate is tilted skillfully so that the collodion flows evenly to all corners, and the excess is removed.

3

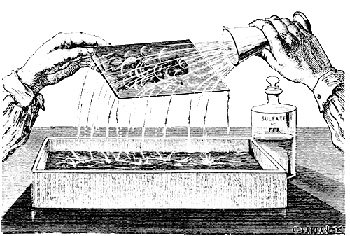

Sensitizing in the silver bath: While the collodion is still sticky (not completely dry), the plate is submerged in a lightproof bath of silver nitrate. The salts in the collodion react with the silver, creating photosensitive silver iodide and silver bromide within the collodion layer. This takes 3 to 5 minutes.

4

Load and expose: In the darkroom, the now photosensitive, wet plate is loaded into a lightproof plate holder. The plate holder is taken into the camera, the protective dark slide is removed and the exposure is made by uncovering/covering the front lens.

5

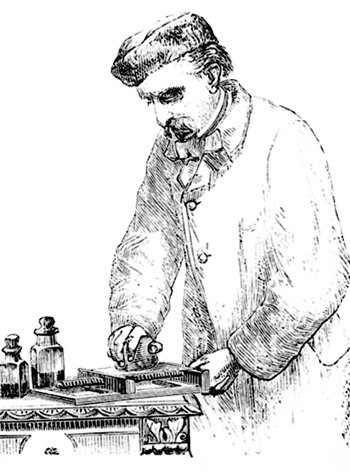

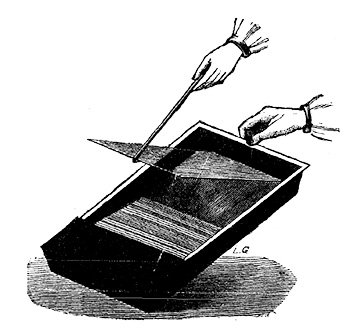

Developing the image: The plate is immediately taken to the darkroom. A developer (usually an acidic solution of ferrous sulphate) is poured quickly and evenly over its surface. The latent image appears almost instantly. When the image is considered fully developed (a matter of seconds), the chemical reaction is stopped by immediately rinsing the plate with water.

6

Fixing the image: The plate is submerged in a fixative, a solution of sodium thiosulphate or “hypo”. This chemical dissolves all unexposed and undeveloped silver halides, making the image permanent and no longer sensitive to light.

7

Final washing and drying: The plate is washed thoroughly in clean water to remove all residual fixative, which would otherwise stain and destroy the image over time. The plate is usually held over a gentle flame (such as an alcohol lamp) to warm it up and allow the water to evaporate, or it is left on a dust-free support to air dry. At this point, it is a finished glass negative (although extremely fragile and almost always varnished afterwards for protection).

Bright future

Since the method was published in March 1851 in the British magazine “The Chemist”, its advantages were soon noticed and collodion was widely and immediately adopted throughout the world. It is interesting to say that its creator, Frederick Scott Archer, did not patent his invention and did not gain any special advantage from it, leaving it completely free for anyone who wanted to use it.

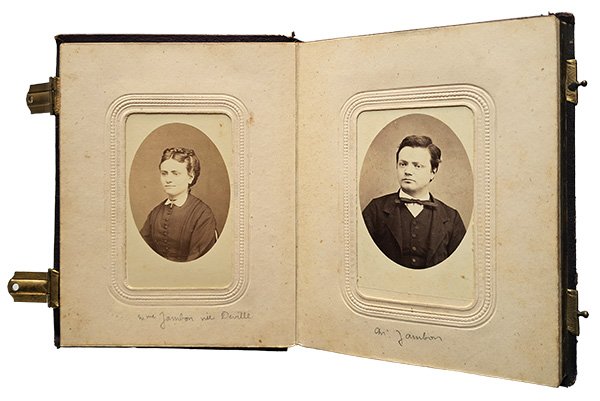

Collodion was very important in photography in general, but it was fundamental to the real fever for small portraits called carte de visite that continued until the 1880s. Huge studios, employing up to 200 people, spread to the major capitals.

Below, a Carte de Visite from the studio of the photographer who invented it, André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri. Disdéri patented the method for obtaining collodion negatives using a camera that could make several images on a single plate, and even details of how to mount them on cards were part of his method. In addition to the patent, he had his own studio and became very rich and famous. Ironically, Archer died in poverty in 1857.

If you are in the Photographic Processes theme circuit:

The wet plate was fundamental in finally producing rich and bright negatives. But its potential could only be fully developed thanks to a new method of printing copies on paper: contact printing with albumen paper.