Leica photography

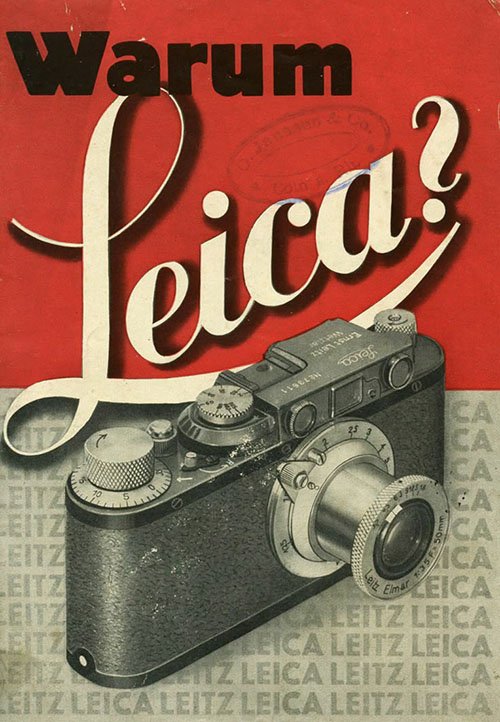

Right from the start, it was clear that Leica meant a new way of photographing. Not only because of the camera itself, but also because film, developing and enlarging photos formed a system unlike anything photographers were used to dealing with.

Aware of this fact, Leitz immediately made this system available with reels for winding the film (which was bought in bulk), developing tanks, enlargers and other darkroom accessories.

Aimed at an advanced and demanding amateur audience, the big battle to win was to convince them that the small camera and its powerful Elmar lens, even with the small 24×36 mm negative, could produce 18×24 cm enlargements with quality comparable to bigger negatives. The promise was that the gain in mobility would not be paid for by a reduction in the quality of the final image.

Extensive literature and exhibitions of “Leica photography” were made available in the main markets. Also very important was the work of brand ambassadors, professional photographers who endorsed and demonstrated the advantages of migrating to the new system.

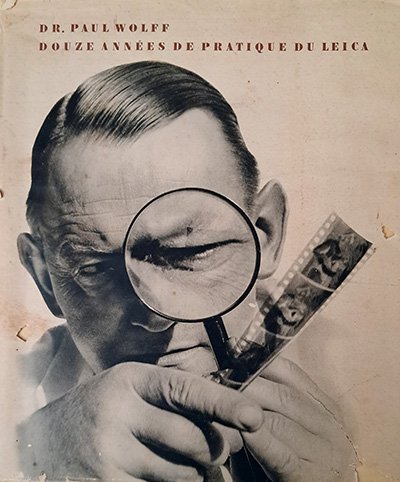

An emblematic case was Dr. Paul Wolff, a medical graduate with academic interests in art history and literature. In the 1920s, he worked as a professional photographer and was one of those who had the chance to try out Leica prototypes. He himself says that at first he doubted that this miniature camera could take good pictures, but after using it he was one of those who helped prove the opposite.

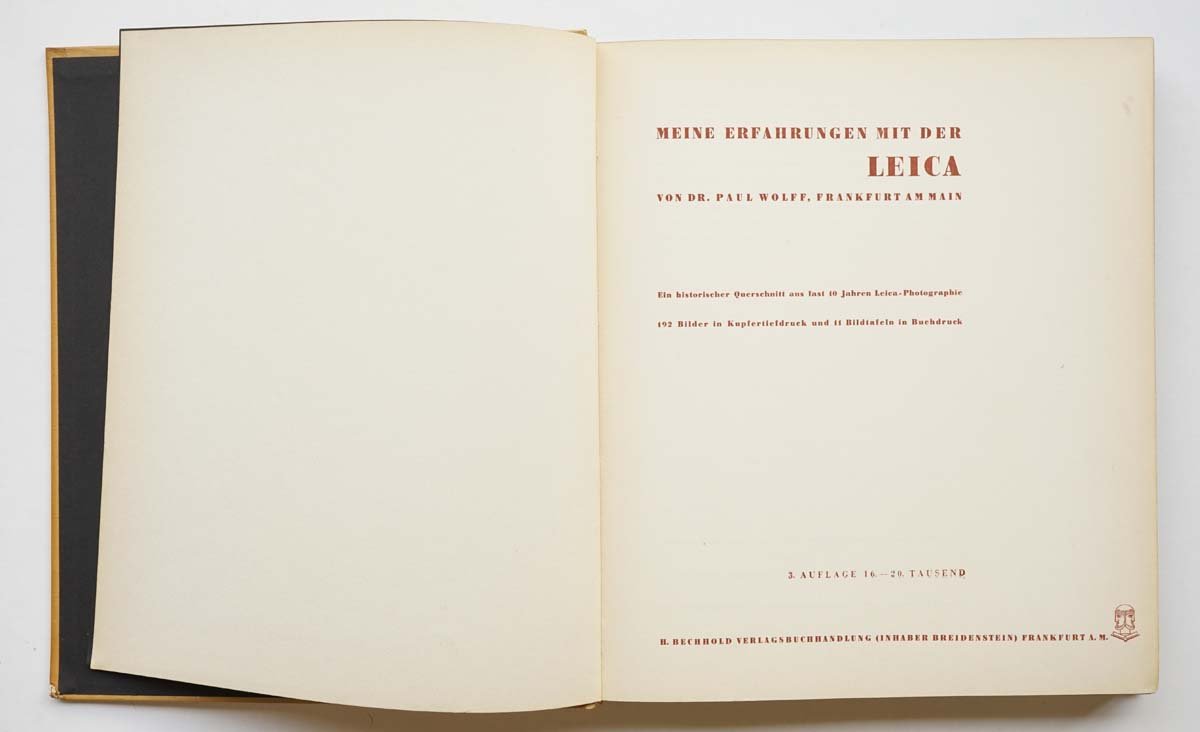

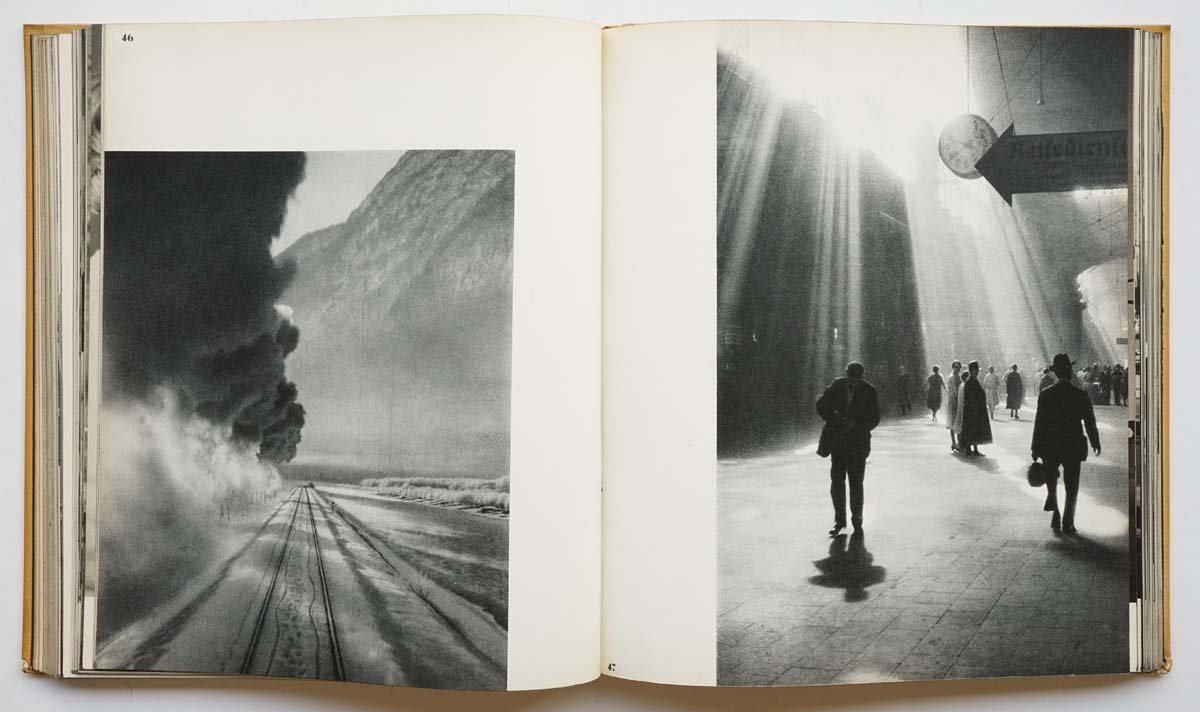

Among many others, in 1933 he published a book entitled Meine Erfahrungen mit der Leica, which would be ‘My experience with the Leica’. A deluxe edition with a format of 23×28 cm and 192 pages. It was soon translated into French, English and other languages.

The book opens with a challenging sentence: “Whoever wants to practice Leicagraphy must be firmly willing to free themselves from all previous traditions and to commit themselves with perseverance to the study of a new way of photographing”. From the outset, the brand took on this air, even this responsibility, of being a break with the past. This idea resonated very well with photographers who felt they were really ushering in a new era by adopting Leica.

Without being a manual in the sense of teaching how to use a camera, as it assumes that the reader already knows the basics of photography, the book also doesn’t go into the details of the Leica’s controls and settings. But it does offer a series of considerations on the act of photography itself.

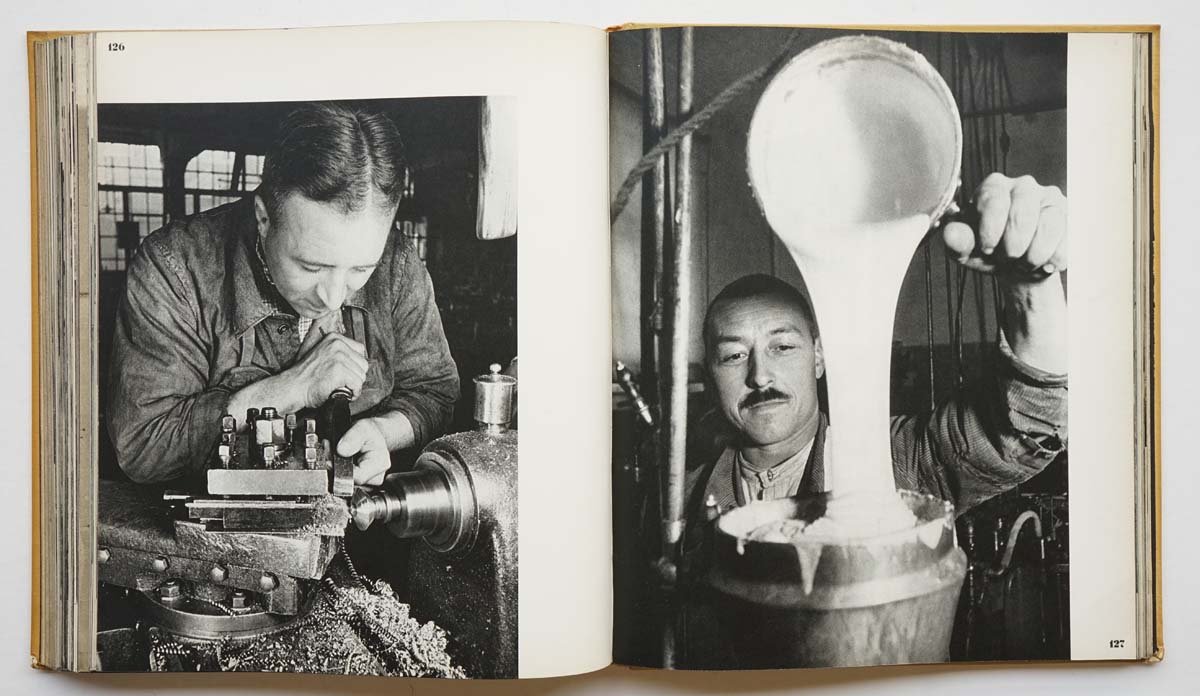

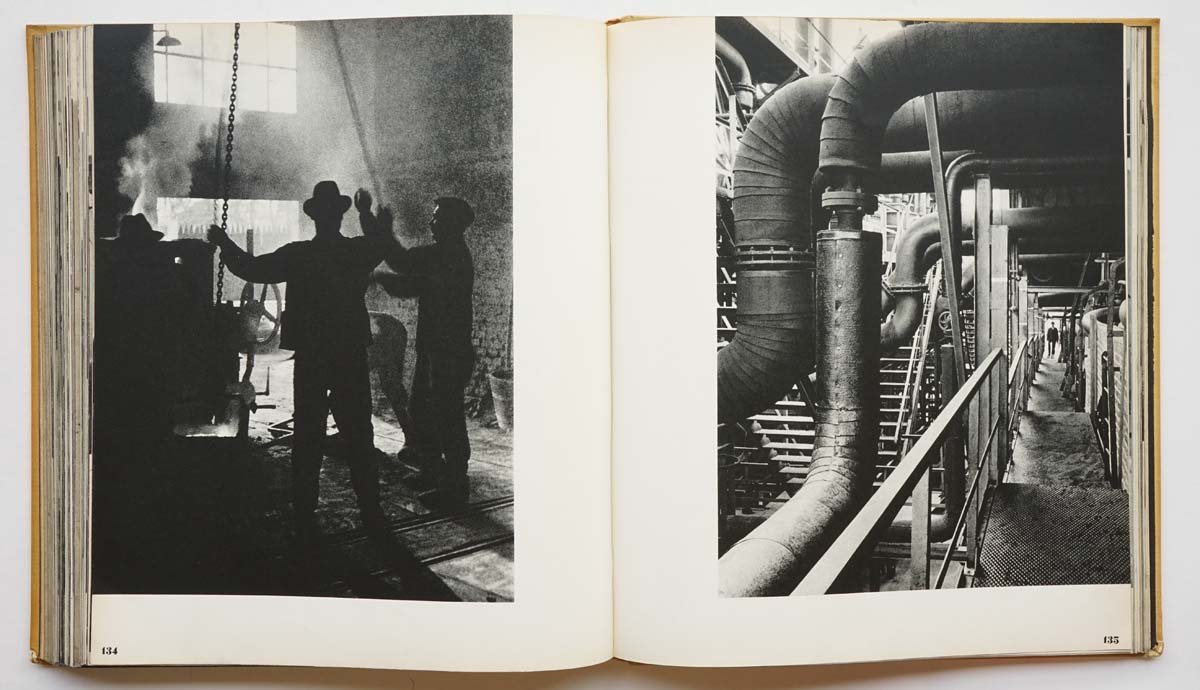

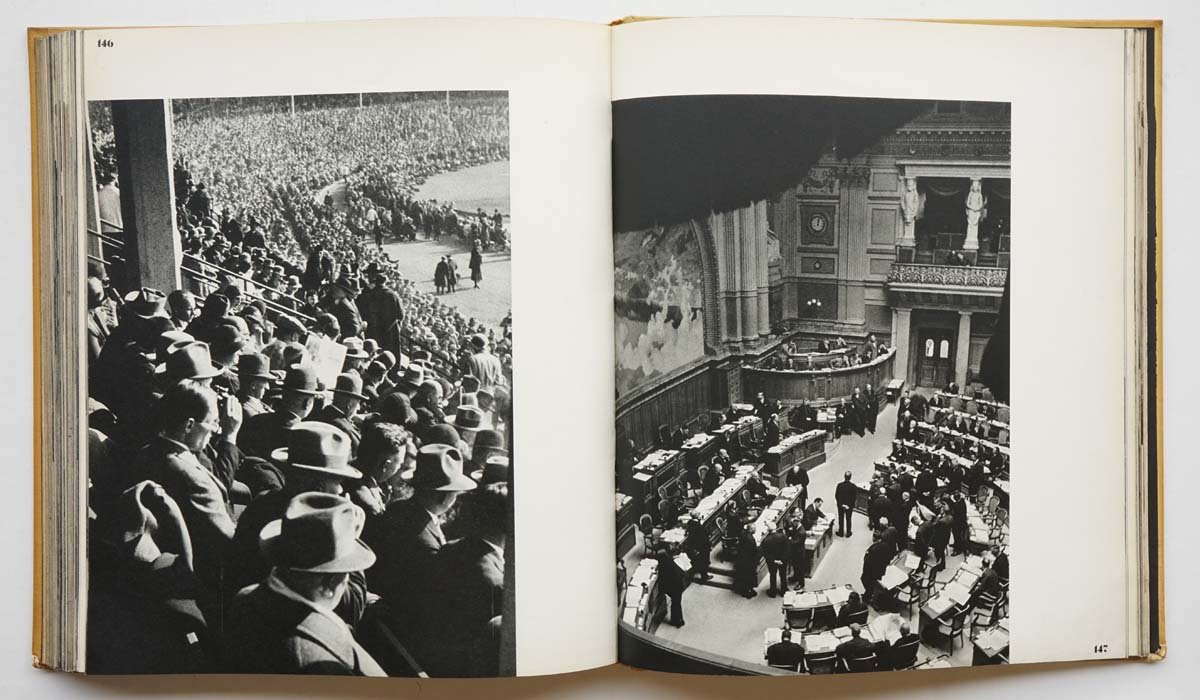

It is divided into themed sections such as landscapes, portraits, the world of work, sports, travel and even scientific photography, among others. He notes the evolution of film since the launch of the Leica in 1925, pointing out the significant improvement that has taken place in the grain of photos. He hints that by exposing more and developing less, grain can be reduced. What’s also interesting is that for all the photos he points out, in a table at the end of the book, which lens (Leica could change lenses from 1930 onwards), film, filter, speed and aperture he used.

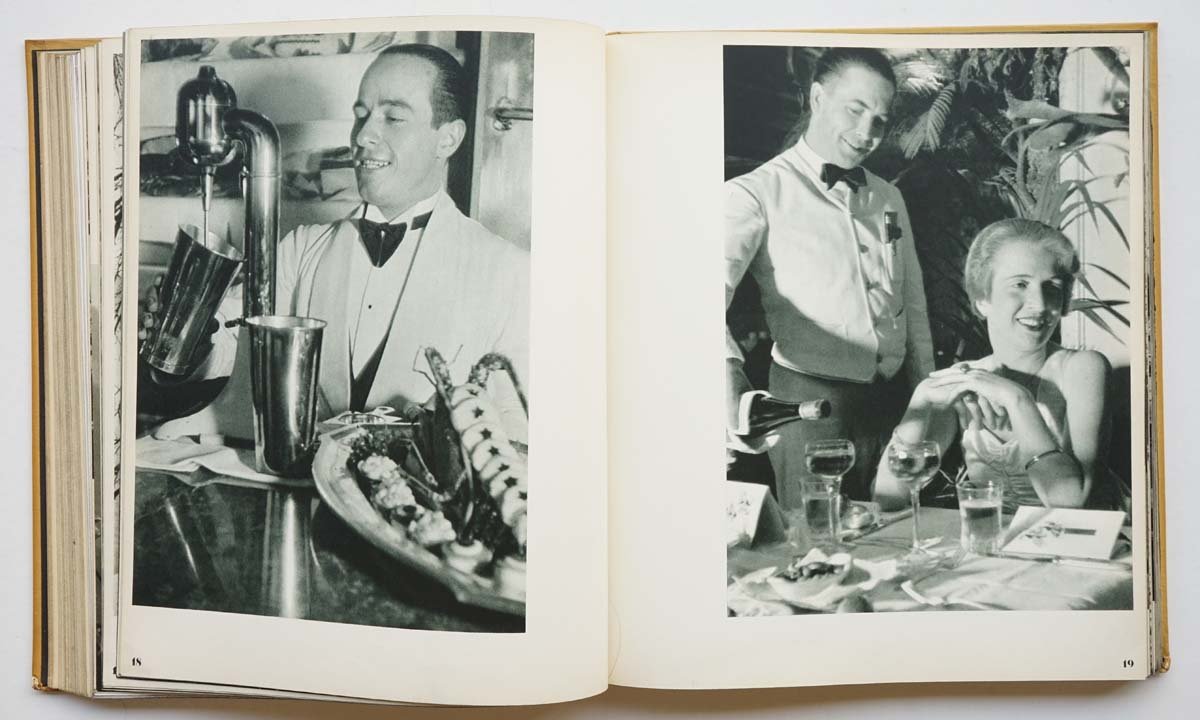

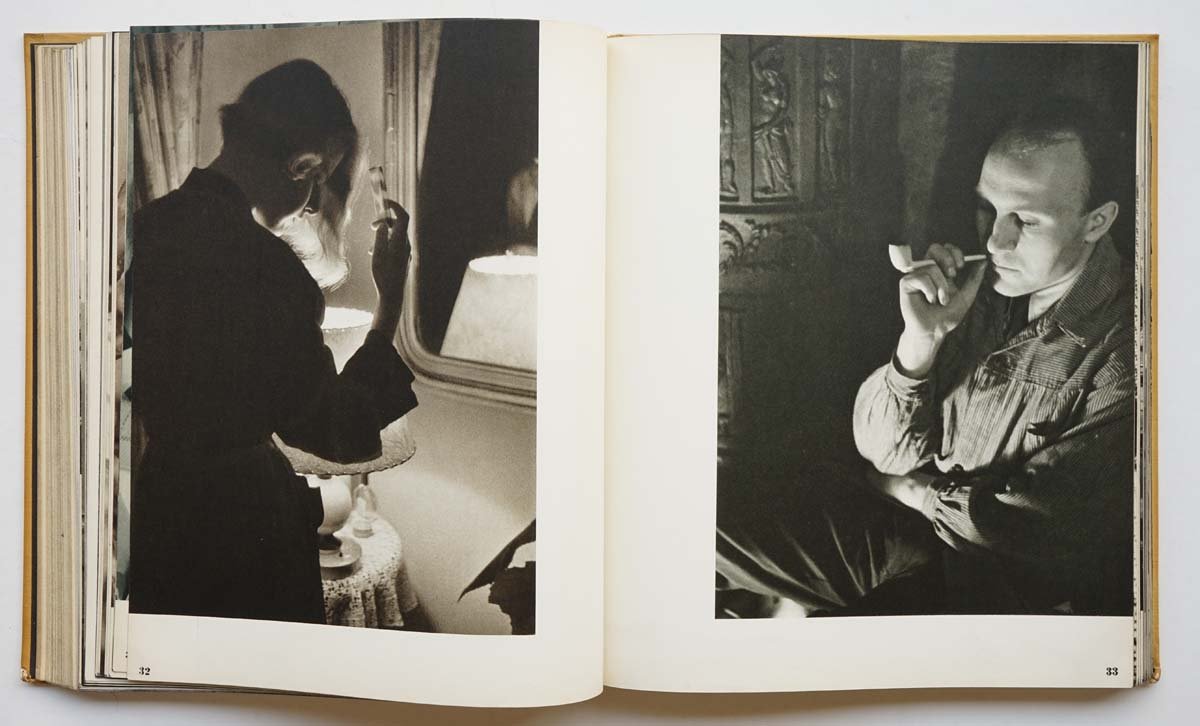

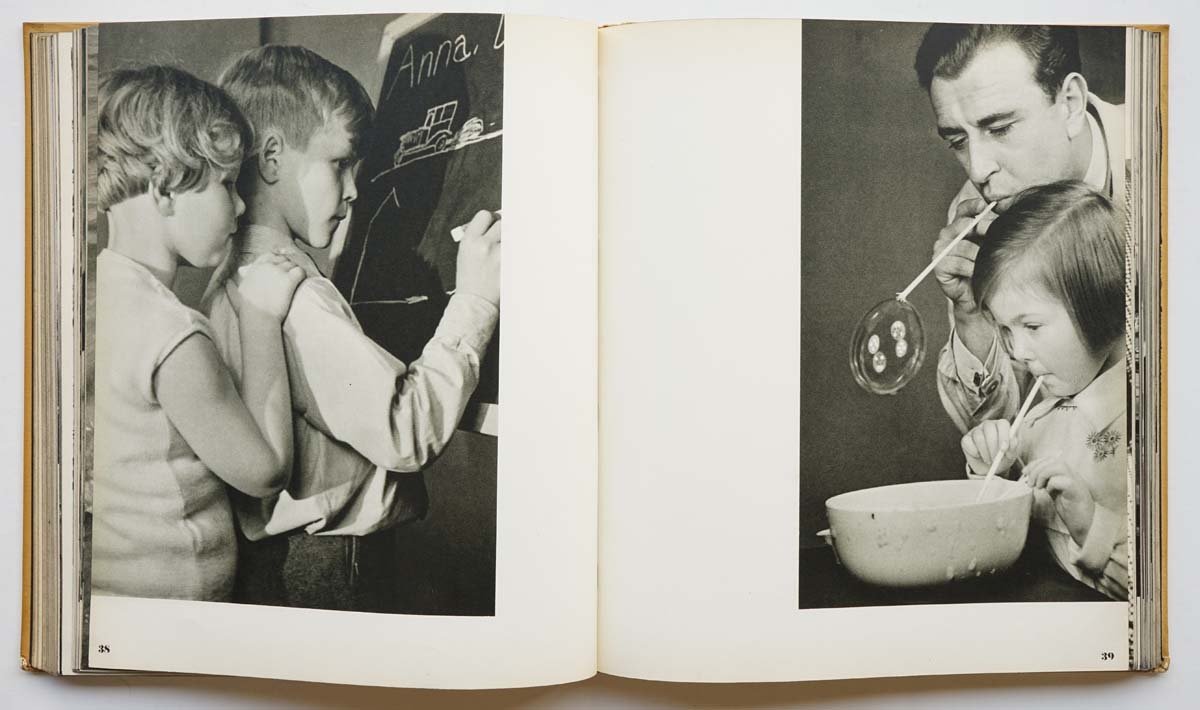

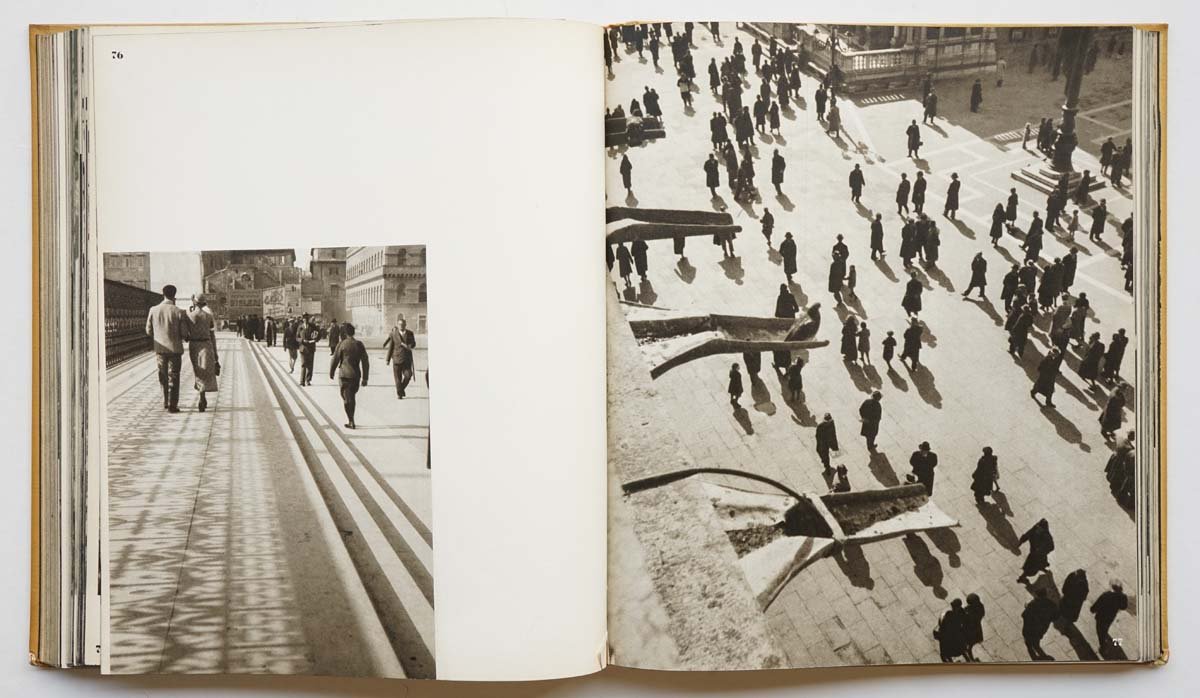

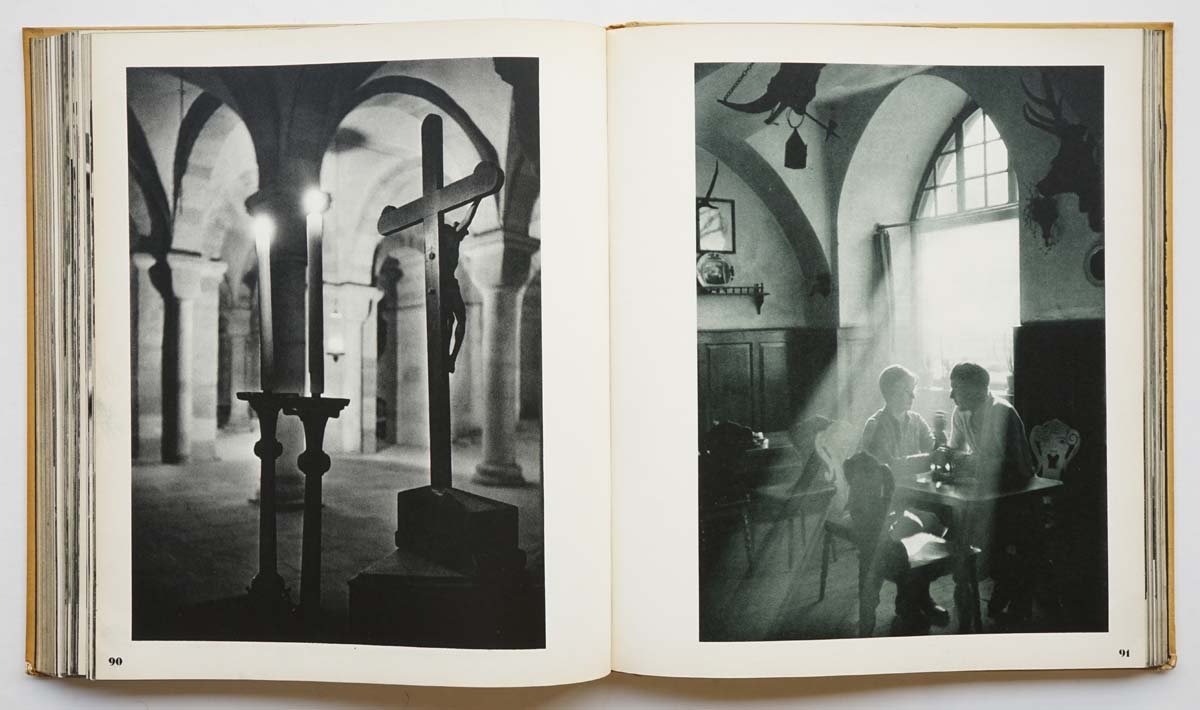

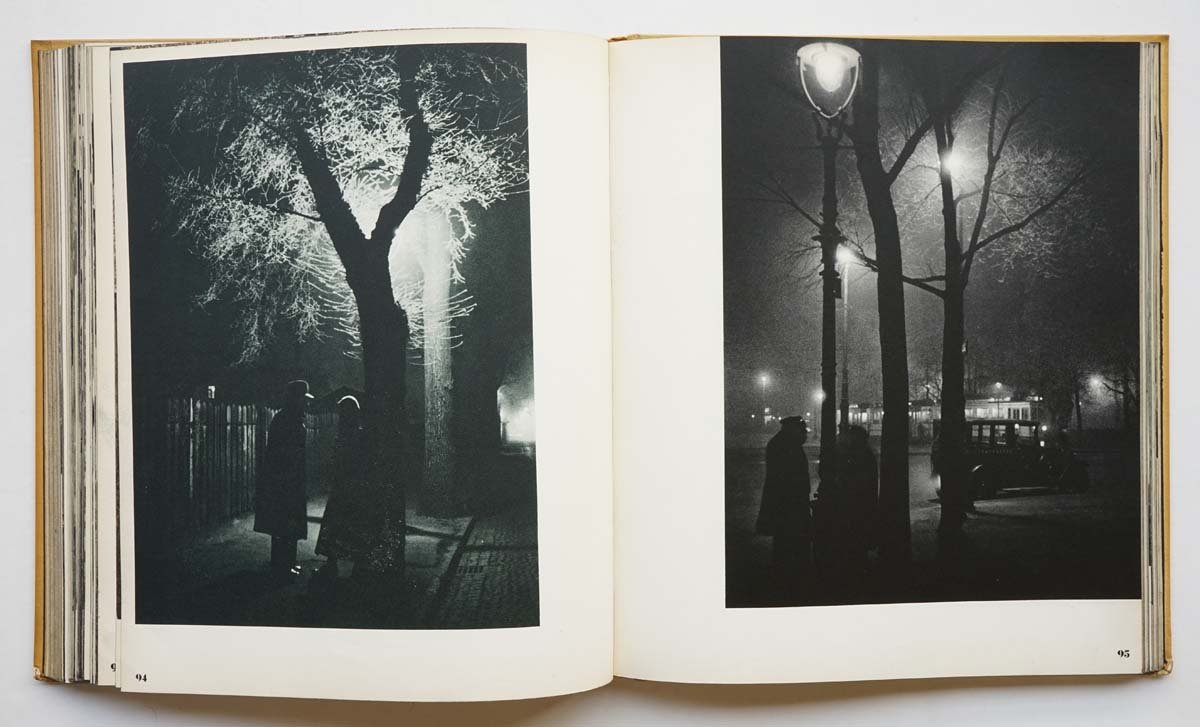

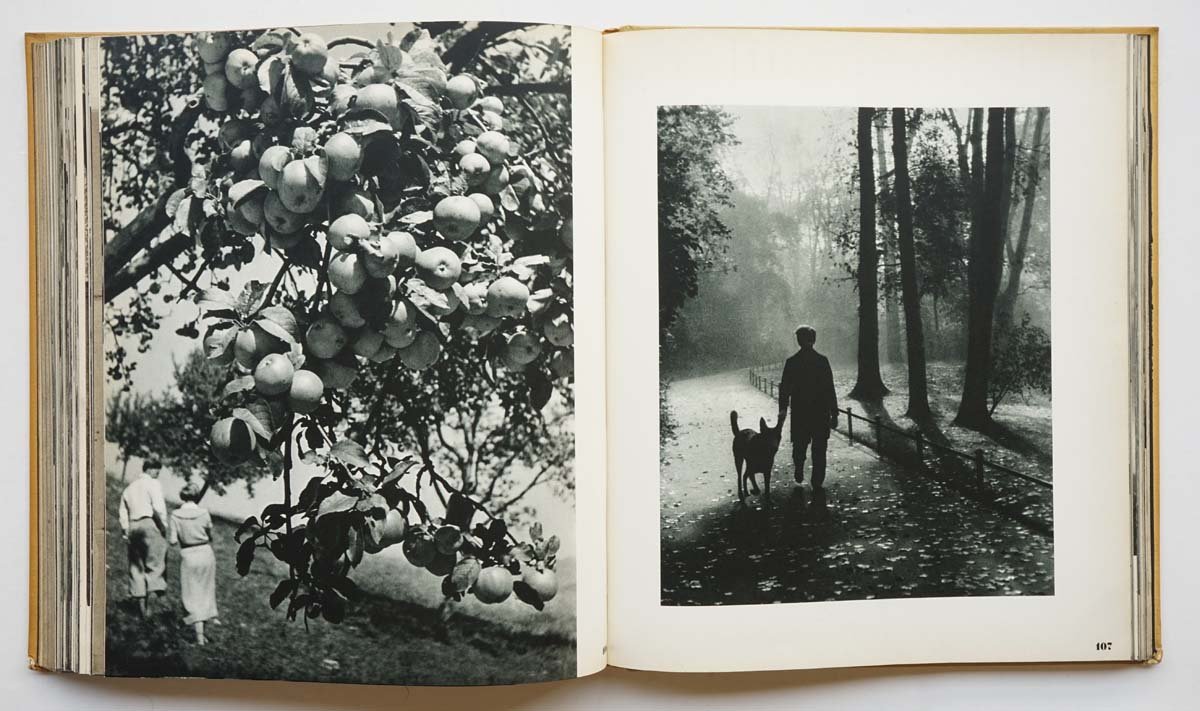

But what’s really interesting are the photos themselves. Today they may seem trivial, but at the time, anyone with a modicum of experience would immediately realize that the subjects, the angles, the lighting conditions would be very difficult, if not impossible, to achieve with traditional cameras. Below is a selection of some pages. Click on the images to see them larger.

For the most part, we can imagine that the photographer simply “took advantage” of the fact that he was there, possibly by chance or for some other reason than taking the picture, but found the scene interesting and … took the photo. In almost all of them there is something happening, something passing, something transforming before his eyes and photography is the capture of that instant. This immediacy, portability, discretion and high photo quality are the hallmarks of Leica.

The world as seen through a Leica

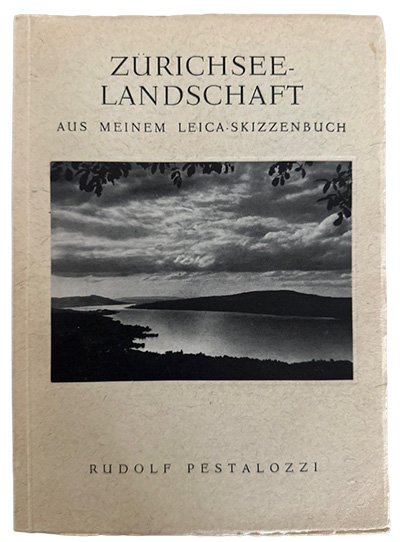

The difference a Leica made led to a new genre of travel books being published. The titles indicated not only the place but also the fact that the photos were taken with the new camera.

Rudolf Pestalozzi, photographer and mountaineer, published several like the one above which reads: ‘Landscape of Lake Zurich, from my Leica sketchbook. What this subtitle implied was that inside would be more dynamic photos than the traditional postcard ones, with more creative points of view. The addition of ‘Leica’ brought contemporaneity to the publication.

The photographer, who used to have to walk down the street carrying tripods and bags of equipment, was a photographer all the time. From afar he was already recognized as such. With the Leica he was just a pedestrian, a visitor, a tourist and only when he wanted to record something interesting in front of him would he pull his camera out of his pocket, record that moment and go back to blending into the environment like everyone else. The photographer thus became a simple flâneur who strolled around, observing and participating more or less as he pleased, as if his identity as a photographer were hidden. This feature of the Leica would transform photography.

Books like these by Pestalozzi and Wolff were the basis for a new kind of amateur photography that found expression mainly in the photoclubs that had been multiplying since the beginning of the 20th century. For these photoclub photographers, it wasn’t enough to take a picture of the children, the park or a walk, it had to be done well. They had to make it look like the one they had seen in the book, magazine or photoclub exhibition. They wanted to leave the mark of an artistic intention, of exquisite technical control, and they were happy to now be able to do so with a lightweight camera that didn’t interfere with their other activities.

Leica in photojournalism

Oscar Barnack and Enst Leitz II’s hypotheses, that there would be a legion of under-served amateur photographers ready to swap their medium and large format cameras for a miniature one that offered quality, were completely confirmed. What they apparently didn’t suspect was that there was also a revolution brewing in photojournalism and that Leica would be instrumental in it.

The basic camera used by the press was in the 13 x 18 cm format and therefore used glass plates. It could be a monoreflex like the Graflex Auto RB or a clap camera like the Deckrullo. This type of equipment gave priority to image quality but sacrificed a lot of portability and speed in the photographer’s work.

However, if we examine what was published in the press in the 1920s, we will see that despite being large and slow to operate, these cameras were consistent with the style of the overwhelming majority of journalistic photos. The images served primarily to illustrate the text. They were usually official photos at public events, portraits of authorities, celebrities, in short, the greats of the time. The stories were about facts and events that were relevant to society. The photos, usually external and in wide views, captured the most significant elements to complete the report, giving it visual support.

However, the fresh memory of the horrors of war, the harshness of reconstruction and the financial crisis generated a feeling of aversion to the big issues. Readers began to feel psychologically exhausted by abstract political theory, arid economic statistics and the constant cycle of global conflicts and crises. They were looking for stories that affirmed individual dignity and emotional resilience. Focusing on the simple and sincere life of an ordinary individual became a form of escapism or emotional affirmation.

The press responded with magazines that began in the 1930s and relied heavily on images, now leaving the text as an auxiliary to a new genre or format: the humanist photo essay. One magazine in particular played a founding role in this new journalism: the American Life Magazine, launched in 1936. But also Picture Post (UK, launched in 1938), Regards (France, launched in 1932), Ce Soir (France, launched in 1937). Photographers such as Alfred Eisenstaedt, Henri Cartier-Bresson and W. Eugene Smith defined the paradigms of the trend.

In the book Eyes Wide Open, 100 years of Leica Photography, Peter Hamilton defines humanist photography by its attempt to substantiate the universality of human emotions, the historicity of images in their position in time, place and context, the focus on everyday life, ordinary people and the photographer’s empathy with the subject.

It is important to add to these points that there is an aesthetic intention that goes beyond or goes hand in hand with the desire to praise and exalt the greatness of humanist themes. This is precisely the photographer’s contribution as an artist, aware that his audience will ultimately see a photo and not the environment or story that the photographer witnessed. You have to know how to tell a story. It is this awareness that leads him to act, to make choices that make his image powerful as a discourse on this reality that he recovers and re-signifies according to his subjectivity. You only have to flip through a book by Henri Cartier-Bresson, André Kertész or Alfred Eisenstaedt, and it’s impossible not to notice and admire that there is always a well-chosen angle, a balanced composition, a hierarchy of elements, a direction of gaze and that these plastic elements of the image are not the work of chance. They give it the strength and power to form an idea, an attitude in our minds. Photographers don’t just capture, they also construct their images.

The Leica was a key instrument in this new photography. The speed with which several images could be taken in sequence, the silence of the operation, the ease with which the camera could be taken out or hidden, the ease of entering the most varied environments without being noticed, of being able to point the camera in any direction, all this gave the photographer the freedom of a hunter, a hunter of images, an association that is very frequent in literature. But we have to be careful, because this metaphor obscures something that is the key to the process, because if the hunt is not the work of the hunter, the images are, to a large extent, a creation of the photographer.

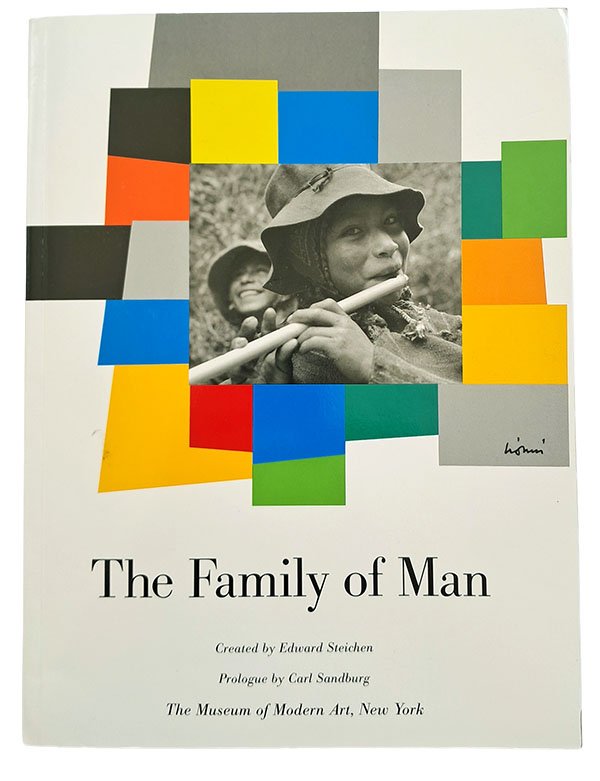

The Family of Man

Looking at what followed, after Leica and countless other brands and manufacturers with the same concept dominated photographic production in the 20th century, it seems that we are still immersed in this vision of the humanist role of photography as its identity and even raison d’être. Even the opposing currents or those that questioned this universalist photography, engaged and focused on the daily lives of ordinary people, did so in opposition, as a reaction to this basic concept and this only shows its strength. It may have been questioned, but it hasn’t been forgotten.

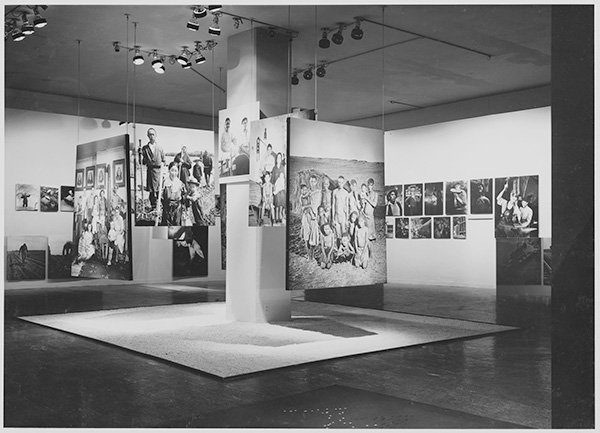

It is common ground that humanist photojournalism was practically synonymous with photojournalism until well after World War II. An extremely important and successful event, which today is seen as a kind of apex of the genre, was the exhibition organized by Edward Steichen for the New York Museum of Art in 1955: The Family of Man.

In the introductory text of the exhibition book Steichen wrote:

“The exhibition, now permanently presented in the pages of this book, demonstrates that the art of photography is a dynamic process of giving form to ideas and of explaining man to man. It was conceived as a mirror of the universal elements and emotions in the everydayness of life – as a mirror of the essential oneness of menkind throughout the world”

He says that they started the selection with around 2 million photographs from all over the world. They selected 10,000 and of these, 503 images from 68 countries and 273 photographers made it into the exhibition which, after MoMA, toured several cities and was a huge success.

Many famous photographers were exhibited alongside unknown ones and the sizes of the prints varied greatly. In every sense, the basic idea was not to hierarchize, not to differentiate and to put all the emphasis on the universality of the human element, as was the premise of humanist photography. The photo above is from the MoMA website. There you can explore a huge number of photos from the exhibition. Follow the link: The Family of Man.

A camera is just an instrument, but I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that Leica played a very important role in triggering transformations that changed photography and made it the driving force behind changes in fundamental values in our society.

To say the least, it is undeniable that humanist photojournalism found in the Leica its instrument of choice and that its influence gave tangible support to ideas that we debate a lot today. I’m talking about themes such as identitarianism, multiculturalism or decolonization. The Family of Man exhibition, as it was a kind of summary of what was going on in the publishing and contemporary art sectors, helped materialize for a whole generation the idea that there is a deep human nature in which all cultural and genetic differences are levelled out and that human beings can, without giving up their differences, live as if they didn’t exist.

If you are in the themed circuit The Leica Revolution, this was the last room. Thanks for visiting. I hope you liked it.