Graflex is certainly much better known for its legendary Graphic Cameras in Speed and Crown versions. They were like the iconic cameras of photo reporters from the 1920s to the 1950s. What less people know is that Folmer and Schwing Manufacturing Company’s (later Graflex Inc.) first big hits were the Single Lens Reflex (SLR) type of cameras.

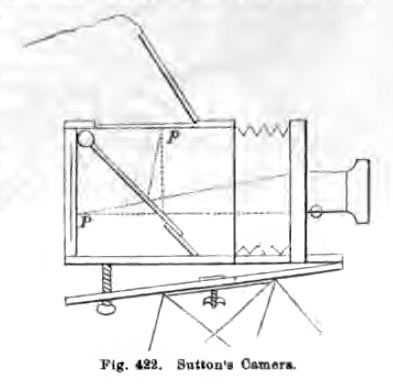

Graflex didn’t invent the SLR. There is probably no specific inventor as the idea is like a natural or obvious development from the camera obscura with the addition of a support of sensitive material. In his 1892 Ausführliches Handbuch der Photographie, Josef Maria Eder cites a reflex camera proposed by Sutton, as early as 1860 (drawing below). But with the slow emulsions available at the time, the speed of action of a SLR was not yet attractive.

The principle of Single Lens Reflex

In every camera, the lens projects an image onto the film. In view cameras, this image can be previously inspected, for framing and focusing, on a ground glass placed right at the image plane, on the rear of camera body. The problem is that in order to take the picture, this ground glass has to come out and the film has to go in its place. On more practical view cameras, such as the Linhof Super Technika, this is done by inserting a film holder between the ground glass and the camera body. It’s faster than many wood view cameras, but it still takes time and the camera needs to be on a tripod during this operation.

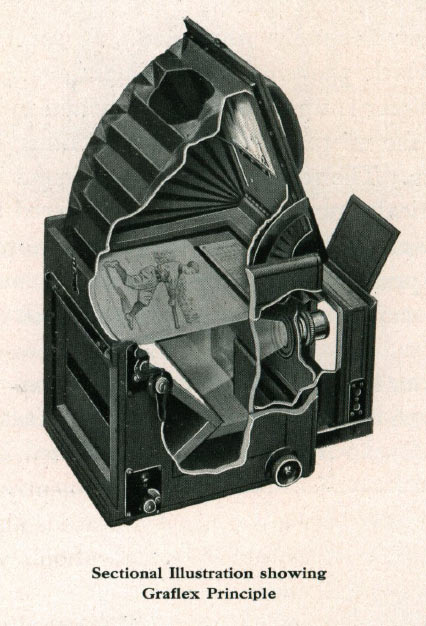

In a monoreflex the film is already in its position waiting for the click. Meanwhile the image is shifted to a ground glass at the top of the camera, as we see in the illustration above (source: 1904 Graflex catalog – Pacific Rim). In this system, the photographer can frame, focus, decide on the right moment and shoot as a continuous act . To take the photo, just press a button, the mirror goes up, allowing the image to pass, and a shutter, on the lens or focal plane, makes the exposure with the preset time. This is very fast and allows for action shots, without a tripod or black cloth.

Of course, viewfinder cameras also allow for snapshots. This was the case of detective cameras, contemporaries of the first Graflex monoreflex. But the advantage of the latter is that the image seen by the photographer was brought directly by the lens that would take the photograph. For photographs at shorter distances and with shallow depth of field the focus and framing can be better controlled in a SLR. Rangefinder cameras, which used a separate viewfinder and offered precision focus, only came later. The queen of this category was undoubtedly Leica, a revolution, but a camera considered miniature for its time and which took a while to be adopted by professionals.

Speeds in Graflex monoreflex

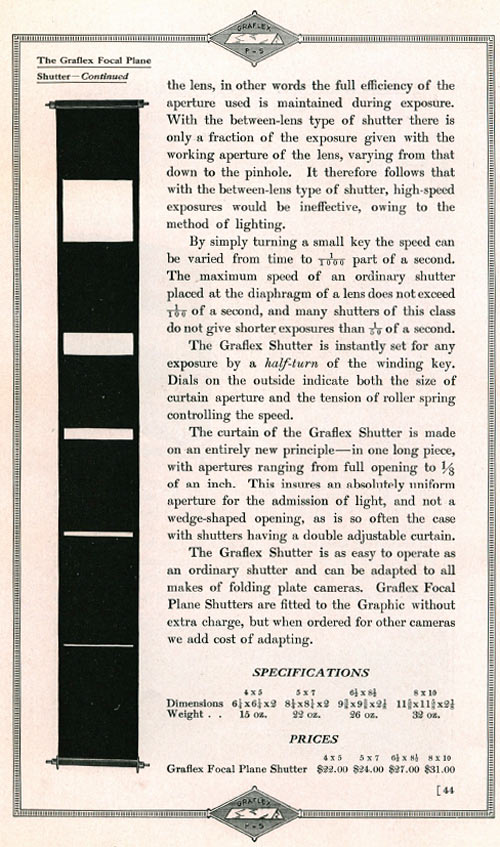

Graflex catalogue – 1910 – source Pacific Rim

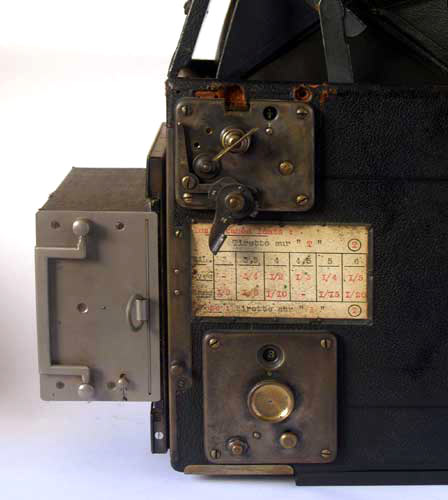

Another advantage offered by Graflex SLR was speed up to 1/1000 s. To understand this we need to study its focal plane shutter. It is a curtain that runs close to the film and, like any curtain, covers and discovers what is behind it. What was very different about the Graflex, compared to other curtain shutters that came afterwards, is that the latter have two independent curtains, one to open and the other to close the passage of light. In Graflex only one curtain was used, but it had 5 different openings.

In the illustration above, from the 1910 Graflex catalog (source: Pacific Rim), we see the curtain spread flat. Short exposures are made by passing a slit of 1/8″ (~3mm) and longer exposures with the longest one being 1 ½” wide (~38mm). In addition to choosing one or another slit, it is also possible to regulate the tension of the spring that will make it run over the film with greater or lesser speed.

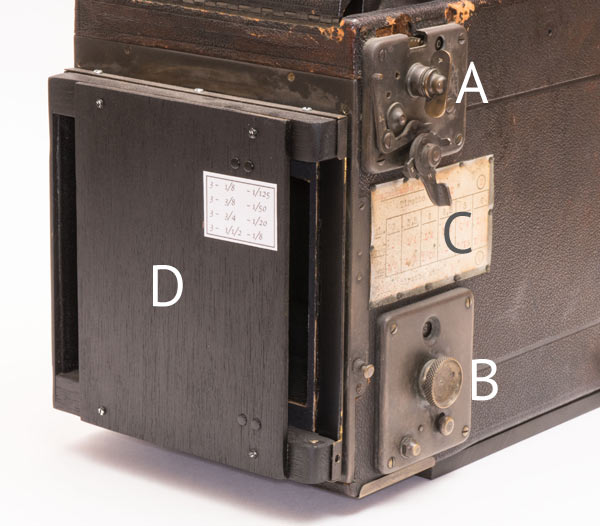

With selector A, in the photo above, you choose the gap size, in B you choose the spring tension. C serves to lock the mirror in position, as it does not automatically return after exposure. D is just a homemade adaptation for the camera to receive standard film holders for 9×12 cm or 4×5″. In it I made a table for tension 3 and the four openings of 1/8, 3/8, 3/4 and 1½”. As the camera is very old I preferred to measure the actual speeds for these combinations rather than trying to adjust the shutter to the factory specifications.

A very interesting comment you read on the page reproduced above presents a problem for lens shutters, leaf-shutters, which makes a lot of sense theoretically, but which I have never seen any more in-depth experimental study on.

The point is that at its highest speeds the time to open and close a leaf shutter starts to be comparable to the total exposure time. Since its blades are in the center of the lens and close to the diaphragm, it’s very reasonable to think that the shutter itself acts as a diaphragm. Even if the lens is fully open, for a while, the shutter blades will be making more use of the central part of the lens, as if it were partially stopped down. The text concludes that only part of the exposure is made with the lens at its preset aperture.

The point is that with a focal plane shutter this does not happen and only with it, even at high speeds, the image fixed on the film corresponds to the effective aperture of the lens. I found this very interesting and would deserve a test with a Speed Graphic, for example, which has both types of shutter.

Weaknesses of the first SLRs

Seeing the image as it is produced by the lens and being able to record it instantly is undoubtedly a huge advantage. But despite the introduction of many SLR cameras since the beginning of the 20th century, among them Graflex, both view cameras and external viewfinder cameras continued to exist and played a very important role in the market. The massive adoption of monoreflex would only come with the introduction of the Japanese ones in the 60s. Some difficulties inherent to the concept explain this diversity in preferences.

Wide angle lenses

A serious problem in the concept of monoreflex is that the very presence of the mirror makes it very difficult to use short lenses. This means that angles of view larger than a normal lens, something like 45º, get more complicated. The Graflex Auto RB works good with a 210mm or longer lens, I think even a 180mm lens might not be able to focus at infinity, in which case it needs to get closer to the image plane. 35mm monoreflex optics got around this problem well, but for many decades applications that relied on wider angles, like architecture or landscape, could not make exclusive use of Single Lens Reflex cameras.

Automatic diaphragm

Another difficulty is that seeing the image from the lens itself is only very good at apertures like f/4.5, maybe f/8… but at f/16 u f/22 the situation gets complicated as the image gets too dim. The entire operation of a fully automatic monoreflex is quite complex and was only resolved in the 60s on 35mm or 120 film cameras. Graflex even offered a preset automatic diaphragm that only closed at the time of exposure, this was for a Super D model starting in 1941, but at that point smaller formats for snapshots were already beginning to dominate the preference of professional and amateur audiences.

Flash synchronization

The high speeds offered by the focal plane shutter mean that the entire image plane is never fully exposed at any time. As the duration of flashlight, especially electronic, is very fast, typically 1/1000 s or less, synchronism is impossible. Double-curtain cameras can still open the first one, trigger the flash and close the second. They usually do this at speeds of 1/60 maximum. But cameras like the Graflex Monoreflex, in which at all speeds are just a slit running over the film, the synchronism gets more complicated and needs to resort to a type of B or T, that is, an open flash that doesn’t always adapt to the subject photographed. Again, a solution was given for this, but it came with the Super D and, as stated above, when the whole concept of these large format SLR was already losing the favor of photographers.

When to use a Graflex Auto RB

Among the Graflex Auto, the RB is of the drop bed type. The focus knob is on the camera body, but after it’s advanced to its fullest a second knob further on engages the rack and the lens can go even further.

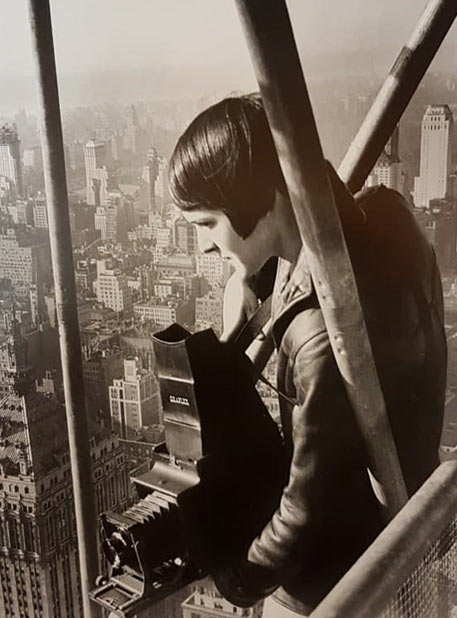

From what has been seen above, this camera is at its best when using lenses that are slightly or much longer than normal. When you can shoot with the lens wide open or in bright places with a few stops down. When you want to take snapshots with the camera in your hand. When high speeds are desirable. It is not difficult to list the classic cases where this combination fits very well into some photography genres.

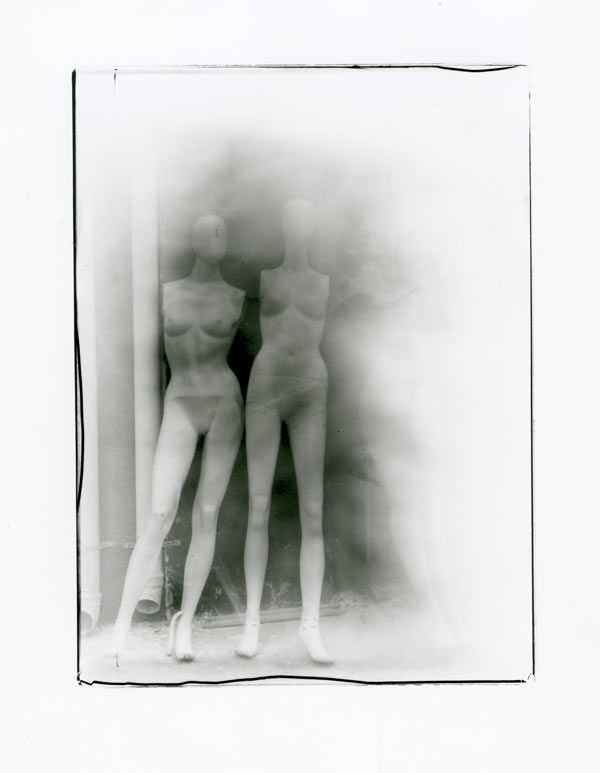

It is an excellent camera for large format portraits with ambient light and shallow depth of field. In this situation it has many advantages over any view camera for the simple fact that the photographer can follow his model and choose the moment when his expression is at its best. With a view camera the solution is usually to stop down the lens to ensure focus in cases where the subject moves while the photographer is loading the film holder, but with a SLR, even the lens wide open is not a problem.

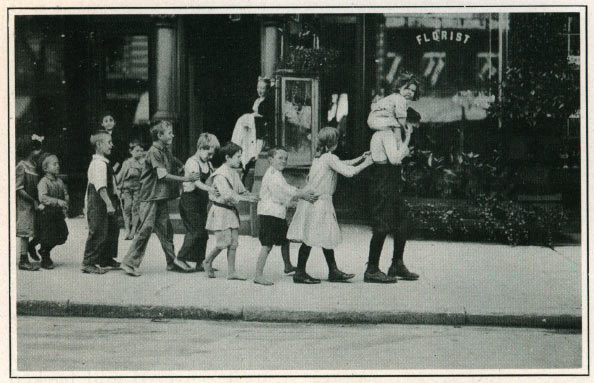

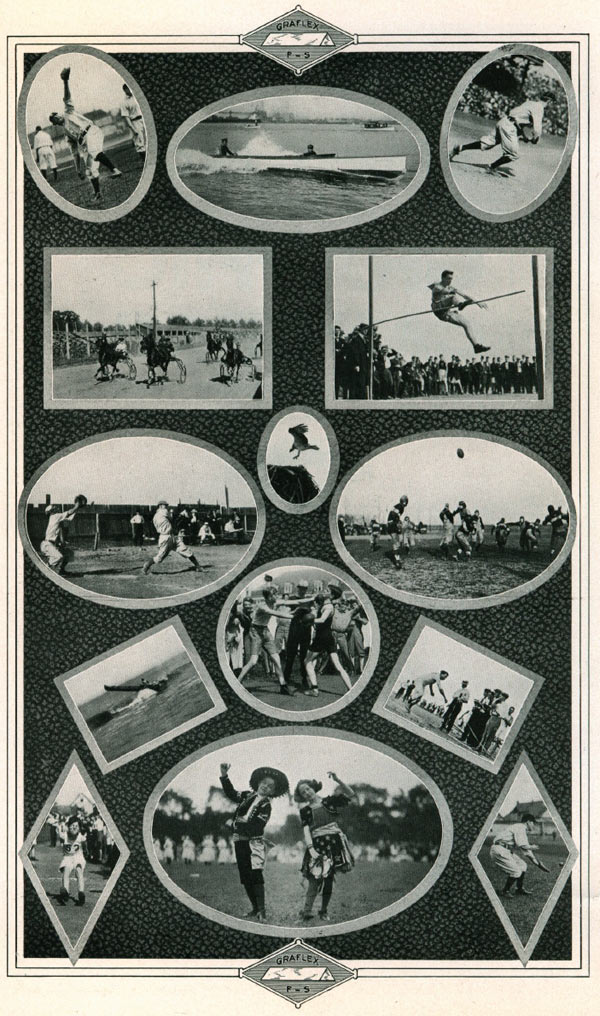

Graflex catalogue – 1910 – source Pacific Rim

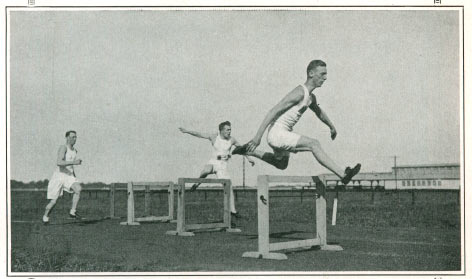

Very effective also for sports shots, action shots, and large-format outdoor snapshots when camera-to-subject distances are longer and call for even longer lenses. With Speed and Crown Graphic, which have won so many Pulitzer Prizes, photographers’ strategy was quite often the opposite. They look for proximity, normal to wider lenses stopped down to ensure a lot of focus, eventually use a flash-bulb and no worries about composition, as the generous 4×5 negative offered a lot of room for cropping. They usually used the sport viewfinder for that. The most important thing was also to choose the right moment and shoot. But the preparation for that was quite different. Graphic cameras would call the photographer into the action while the Graflex SLR cameras would place him more as an spectator.

Naturally, in this 1910 Graflex catalog (source: Pacific Rim) the featured photos all go in this direction of making the best use of speed, framing, focus and long lenses, as only a SLR with a focal plane shutter could offer.

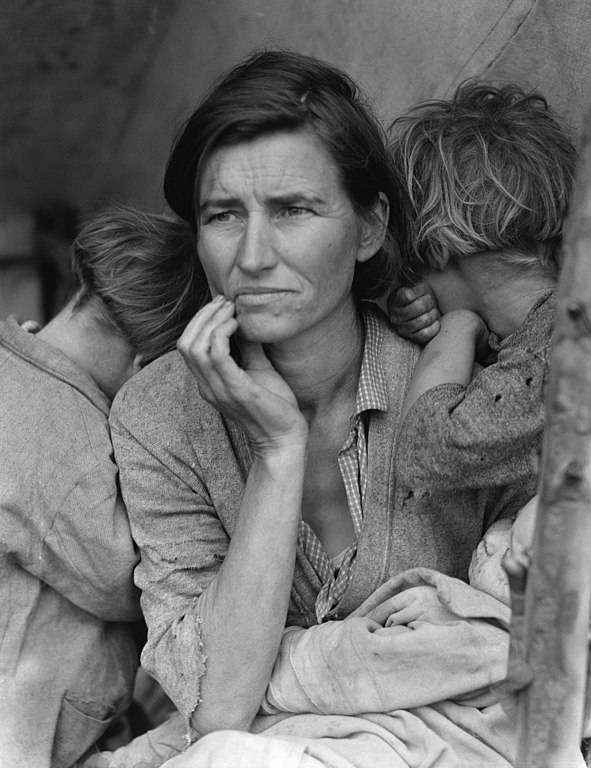

A historical example of the type of photo in which a large format SLR can render an image at its best is the Mother Migrante photo, by Dorothea Lange, taken in 1936 with a Graflex D. I think it would be an impossible photo with a black cloth, tripod, and all the ritual that a view camera demands. Probably all this preparation would attract the attention of Florence Owens Thompson and there would be no such expression on her face, an expression that became a symbol of the American crisis in the 1930s. One could argue that in 1936 a Leica could easily make the same photo with even greater discretion and spontaneity . I agree, in part, because then we would lose the beauty of a 4×5 negative. I think this format plays a very important role in this photo. A small negative would make a more rustic photo, but this photo gives us a vision that is simply epic. It emanates grandeur.

In practice

Ergonomically, the Graflex Auto RB, after being loaded and adjusted, is quite reasonable if the weight is not an inconvenience. Hold the camera with both hands, leaving your left thumb free to trigger the shutter. But it’s important to say that the point of view will always be from something at waist level and not that of the photographer’s eyes. This usually also calls for a greater distance from the subject being photographed.

This one from the collection came with a magazine for 24 photos on film in 9×12 cm format (picture below). It would be great for action shots providing quick film switching. But this accessory adds a lot of weight and nowadays nobody goes shooting in large format by dozens of pictures.

So I made this modification to receive the standard double film holder, like this Linhof in 9 x 12 cm. The operation is slower but lightens the weight and gives even more reliability as the multiple magazine is more susceptible to failures. This Graflex has a revolving back which is very important as I find it rather impossible to take a photo with the camera rotated 90°. With this possibility it is easy to switch between portrait and landscape photographs.

The lens plate has a side adjustment that allows for a front raise, but I don’t see much use in a camera that is primarily intended for longer lenses and tripodless photography.

One accessory I needed to install was this reading glasses. I cut both sides and made two handles in 3D printer. There must have been something like that at the time, I can’t believe every photographer had perfect sight. The problem is that it is not possible to fit the face to the viewfinder using regular glasses. Without fitting, too much light leaks onto the ground glass and it is difficult to see the image. So this was the solution for the short distance between the image and the top of the viewfinder.

I took few photos with this camera as the adaptation to standard film holder is recent.

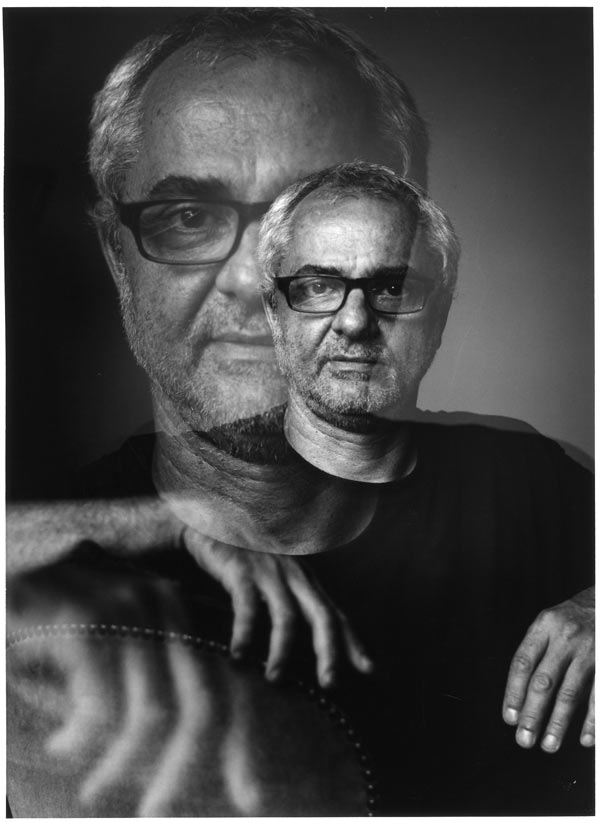

This is an old one that was enlarged on a very rustic Foma paper. I find this possibility of close-ups on 9×12 cm portraits interesting. The lens was the one that came with the camera, a Tessar 210mm f/4.5.

This was the result of a terrible light leak with the old magazine. But in the end I decided to print anyway. With the negative on the enlarger chassis I scratched the side of the emulsion to give this irregular outline.

Even a half-length portrait and a sharp lens like the Tessar, 180mm and wide open at f/4.5, the background blur is quite pronounced.

This was an accidental double exposure that ended up being printed as well.

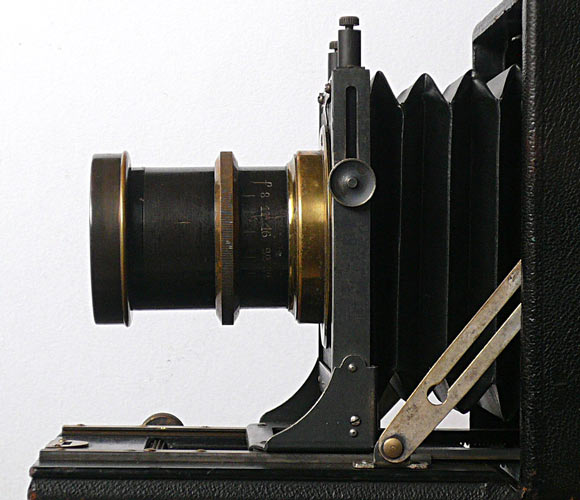

I also mounted this Emil Wusche lens, a Rapid Rectilinear 300mm f/8. The picture below was made with it.

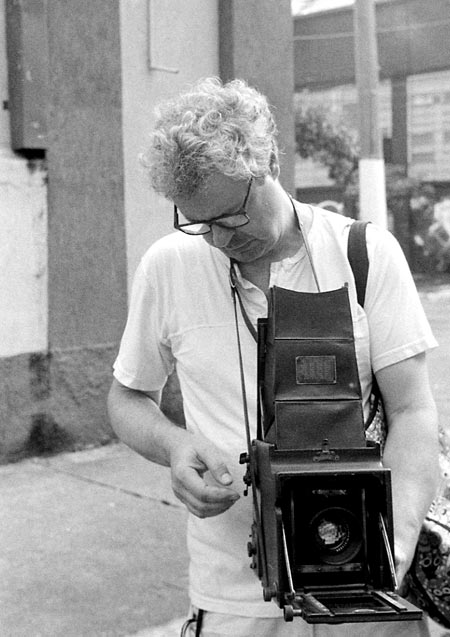

To close the point about the Graflex Auto RB in practice, this is me, with it, photographed by Ricardo Yamada using a Leica IIIC and Summitar 5cm f/2

Graflex Inc.

Initially called Folmer and Schwing Manufacturing Company, was founded in 1887 in New York to manufacture various metal products in the area of gas lighting. With the decline of this market they experimented with bicycles and also cameras. The first camera was in 1899. Several SLR models were released but all sharing the same basic features with some format and functionality differences. Success was great and soon they left bicycles to concentrate on the growing photography market. In 1905 they were acquired by George Eastman and moved to Rochester. But in 1926, due to anti-trust regulations, Kodak was forced to sell its professional equipment division and so the company was renamed Graflex Inc.

This model from the collection is a Graflex Auto RB and was manufactured between 1909 and 1941 according to Camera-Wiki. The RB stands for Rotating Back. As stated above, the main feature of this model in relation to others in the series is the extra extension of the bellows.

All of its features that make it an excellent portrait camera remain valid today. For those who want to shoot 4×5″ portraits, or action photos in this format, it remains a great option, as over the years this type of photography has migrated to roll films in smaller sizes and no large format camera manufacturer has taken a chance on these fields.

Below is the beautiful cover of the 1910 catalog that was much consulted throughout this post and can be found on the website of Pacific Rim along with many other catalogs from Graflex and other manufacturers. Another very valuable source about Graflex is the graflex.org website, it worth very much a visit.