Aplanat | Steinheil

Steinheil is one of the great names of the German optical industry, even before the invention of photography. It all started when Carl August Steinheil (1801-1870), at the age of 22, gave up a career in law to devote himself to astronomy. He went to Gottingen to study mathematics with none other than the brilliant Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777-1855). In 1835 he became a professor of mathematics and physics at the University of Munich and already in the 1930s he began making telescopes, quickly gaining a solid reputation as an authority on the subject.

Carl August Steinheil (1801-1870), photo from 1850

–

Carl Steinheil was also involved in developing technology for many other applications, such as the electromagnetic telegraph. What emerges from reading about his life is that he was one of those restless, generalist minds, like so many others in the 19th century, who, from a solid background in the basic sciences, couldn’t resist passionately attacking every question, however scattered, that the scientific method could address.

In 1852, the King of Bavaria, Maximilian II, asked him to settle permanently in Munich to devote himself especially to the field of applied optics(Corrado d’Agostini). I find it interesting to look at this historical and biographical data to realize that although the pioneers of photography such as Nièpce, Daguerre, Reade, Bayard and to some extent even Talbot, were something of dilettantes or dedicated amateurs, photography soon became a scientific and economic subject that stirred up the political and academic world. The dilettantes didn’t disappear, many photographers, even weekend photographers, contributed in various ways to inventing and perfecting the photographic process. But at the same time, the production of photographic images mobilized enormous energy from the big names in science, industry and political and institutional leaders. It’s also interesting to observe the figure of the entrepreneurial researcher, scientist and businessman, which was very common in the 19th century, but which no longer seems to have a place today.

Maximilian II’s request made perfect sense, as Munich had been the center of optics development under the leadership of the great physicist Joseph von Fraunhofer (1787-1826), but with the invention of photography, Vienna had become a strong competitor, with names like Petzval and Voigländer working there, who were really just the tip of a new iceberg that was rapidly forming.

It was in this way that factories, raw materials, trade agreements, patents and all the knowledge involved in optics, the study of light, colors, chemistry, in short, all of science, overnight became the business of political leaders, kings and princes, who managed incentives, vied for talent and competed with each other for the markets that were opening up. They also had to learn to move around this new chessboard. What a difference from the days, not so long ago, when only wars could bring power and wealth to royal families.

Hugo Adolph Steinheil (1832-1893)

–

But the Steinheil name goes far beyond its eclectic founder. For photography specifically, it is in the production of his son Hugo Adolph Steinheil (1832-1893) that we will find some of the main achievements that really marked the history of photographic optics in the second half of the 19th century. Adolph didn’t get on very well with his father, as they were opposites. While Carl changed the subject all the time and started more projects than he could finish, it is said that Adolph was the persevering type and couldn’t let go of a problem until he had found a solution. It was this obstinacy that made him work 12 hours a day for 15 years, starting from the establishment of the firm in Munich, to develop a new family of lenses that would be a revolution in photographic optics(Corrado d’Agostini).

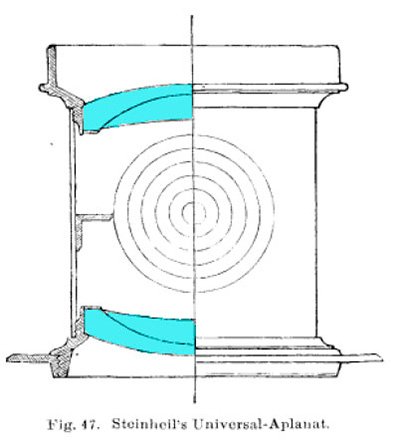

After Petzval’s lens, it can be said that nothing was as significant as the Aplanats, designed by Adolph Steinheil in 1866 (and simultaneously and independently by Dallmeyer, also German, working in England, who launched the same concept under the name Rapid Rectilinear). Adolph had the collaboration of his friend, the mathematician Philipp Ludwig von Seidel (1821-1896), from the University of Munich, who had developed a set of equations that made it possible to simulate the oblique rays falling on the lenses and thus predict, using calculations alone, the effects of each optical concept/design on the quality of the final image. Seidel managed to mathematically separate the different aberrations that deteriorate the periphery of a lens image.

It was with the use of this formalism that Adolph Steinheil was able to debug the concept of two symmetrical optics around the diaphragm and launch a line of lenses with different angles of view and generous apertures for the time, which (some) reached up to f/6. The advantage of symmetry is that it automatically corrects distortions. This was very important in architectural photography where vertical lines appeared curved when using the landscape lenses available at the time. Another important use in which distortions were a major problem was in the reproduction of documents and maps.

The concept of Aplanats proved to be flexible and various versions, more angular and less luminous for landscapes or more closed and more luminous for portraits, came from the basic idea of symmetrical lenses. Not that symmetrical lenses in themselves were anything new, their advantages had been known since at least 1841, but Adolph Steinheil had the idea of using glass in an innovative way. The doublets, to correct chromatic aberration, had until then usually consisted of a crown glass and a flint, but in the Aplanats, according to Kingslake: “The real clue to the construction of the Rapid Rectilinear [the name of the “Aplanats” in the design developed by Dallmeyer] lies in the choice of glass. The two types should differ as much as possible in refractive index and as little as possible in dispersion index.” So Steinheil and Dallmeyer used two flint glasses that formed, among what was available at the time, the combination that made it possible to achieve the maximum approximation of the dispersion indices and the distance between the refractive indices .

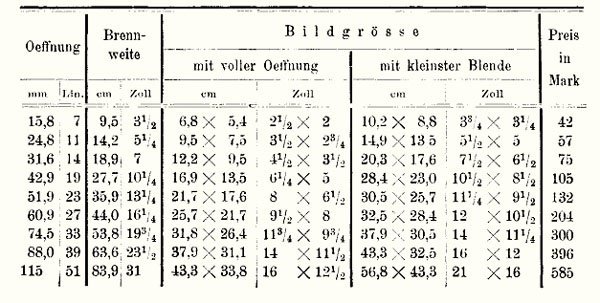

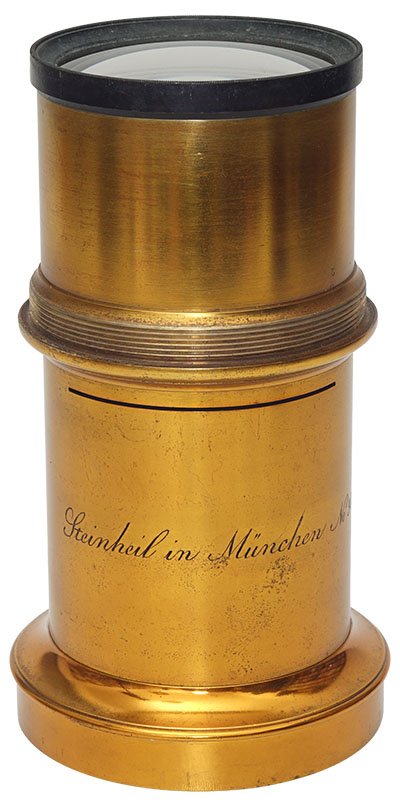

This specimen from the collection is the Aplanat Universal of 27 linie. Linie is a measurement that was used by scientific instrument makers all over Europe but, unfortunately, it wasn’t exactly the same value for all of them. Steinheil’s linie corresponds to 1/10th of an inch. It is therefore the same as 2.54mm. Applied to photographic optics, this is the measurement of the useful diameter of the front lens, which is 69 mm. Therefore, referring to the table above in Josef Maria Eder ‘s 1893 book on optics, it corresponds to a focal length of 440 mm. According to the table above, it covers a format of 257 x 217 mm wide open. Calculating the diagonal, we get 336 mm. Calculating the angle of view, we get 42º. In the case of a minimum aperture, which for a lens like this would be something like f/64, the table says 433 x 325 mm, and redoing the same calculations gives an angle of view of 52º.

The maximum aperture of the lens is given in the first column of the table: Oeffnung, but this is still not the f stop we’re used to, it’s the entrance pupil of the lens, it’s the apparent diameter of the diaphragm which in this case is of the Waterhouse type. To convert to f/stop, you need to divide the focal length by the entrance pupil: 440/60.9. This gives us f/7.2.

This difference in angle of view of 42º when at f/7.2 and 52º when at f/64 illustrates how “you can’t have it all” in optics. Whenever you win on one side, you lose on the other.

Mounted on a Thornton Pickard Royal Ruby Triple Extension 18×24 cm

–

Whether or not to restore

When I bought this lens from a friend, it was in the condition shown in the photo below. There is a lot of discussion among collectors as to whether or not we should restore these pieces of equipment or leave them with the marks of time and simply prevent new ones from appearing.

For me, a lens is first and foremost an instrument with which I take pictures. It’s not an object of worship. When I see that the “marks of time” are more like “marks of neglect”, if I think I have the means and knowledge to bring the object back to a state more similar to when it was new, I’m all hands on deck.

Unless the marks of time have been caused by some sloppy but interesting owner. In that case, the marks could be indices of your relationship with the instrument and the photograph and could thus be pieces of history that should be preserved. But unfortunately I don’t have anything in this category.

But when it was anonymous people who almost destroyed the object and it only survived because it was made by someone who wanted it to last forever, in those cases, let’s say I respect the will of the person who made it more than the neglect of the person who used it.

The thing about these lenses is that they have been varnished with shellac, which is a wonderful natural varnish that protects the metal very well. But over time it darkens. If the lens isn’t treated carefully, the varnish scratches, peels and the metal begins to be attacked by the weather and the lens can end up like this Steinheil was, or even worse.

So, a friend who is a goldsmith cleaned the metal properly, without leaving sandpaper marks, steel wool and other absurdities that we see around…

…and to prevent it from oxidizing again, I applied a layer of lacquer that will keep it intact for the next 50 years or more.