Willian Henry Fox Talbot – Daguerreotype by Antoine Claudet, c. 1844

–

Fox Talbot’s calotype

At the same time, and unbeknownst to each other, the Englishman Willian Henry Fox Talbot was, like the Frenchman Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, developing a photographic process. Many people around the world were looking for a way to fix the images from the camera obscura, but these two processes, the daguerreotype and the calotype, were the two that really established themselves as the starting points of photography.

It has been known since the time of the alchemists that some compounds containing silver are sensitive to light, that is, that they change their characteristics when exposed to light. That the Camera Obscura forms images of what is in front of it was also not news to anyone at the beginning of the 19th century.

The two missing links for Talbot and everyone else investigating how to record the Camara Obscura images were:

1- Which support to impregnate with which silver salts in the dark, and then expose this support in the camera obscura to alter differently the bright parts from the dark ones and in this way record that image ?

2- After removing the exposed support, how can we prevent the parts that inside the Camera Obscura were spared by the absence of light, i.e. the shadows of the image, from being transformed by the ambient light?

The medium Talbot chose was paper. Good writing paper, free of impurities.

The silver entered the process not in its pure form, as in the daguerreotype, but in the silver salt called Silver Nitrate. This salt, conveniently for the process, is not sensitive to light and so can be handled under normal lighting conditions

To make the silver “change salt” to one that was sensitive to light, Talbot soaked his paper in a solution of sodium chloride, or table salt.

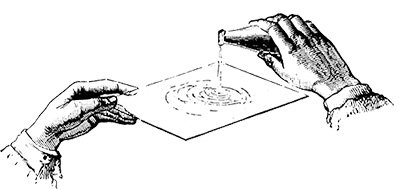

Once dry, the paper was then bathed in a strong solution of silver nitrate. This operation had to be carried out in a dimly lit environment. What happened in this second bath was that some of the silver “released” the nitrate and “bonded” with the chlorine, forming silver chloride, which is sensitive to light and subject to darkening when exposed to it.

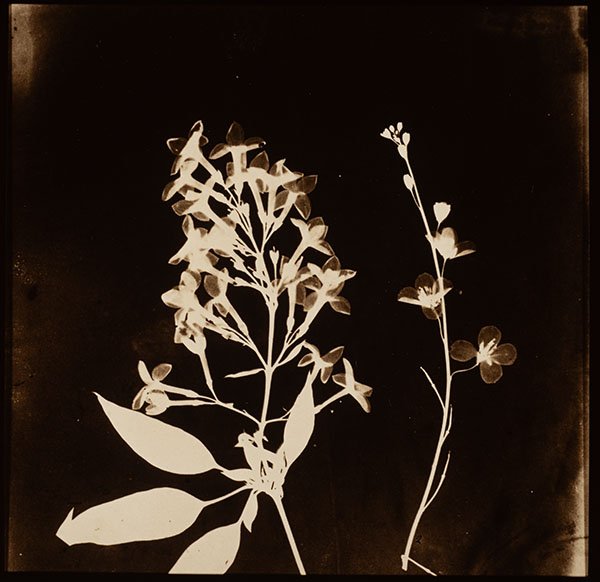

Botanical species – Photogenic drawing – Fox Talbot – 1839

–

Before going to the Camera Obscura, Talbot experimented with many contact prints. Mainly plants or laces were sandwiched between glass and sensitive paper and exposed to the sun. This produced very sharp, contrasty and vibrant silhouettes. Encouraged by the result, Talbot went on to the great test that would be the camera obscura.

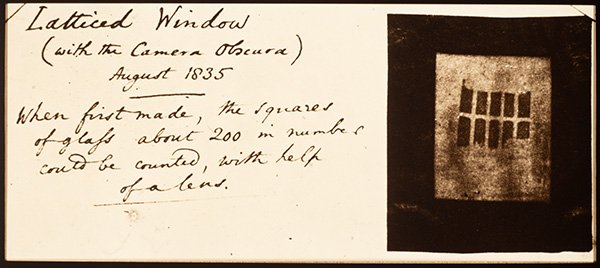

But the sensitivity he was able to achieve in preparing the paper was insufficient for this new situation. Even in the brightest areas, the light in the Camara Obscura image was too weak and it took too long to expose enough to get a good record. He remedied this problem somewhat by using very small cameras with a format of just over an inch, which therefore produced brighter images. This is the case of the photograph below, taken in 1835.

Window in Lacock Abbey, Fox Talbot’s residence – 1835.

–

Another problem, perhaps even more serious, was that when the paper was removed from the Camera Obscura, or even from the contact press, the parts of the image or silhouette that didn’t receive light began to receive ambient light and underwent the same transformations, rendering the image unusable. The entire paper darkened.

While still in the dark or in very low light, it was necessary to “wash”, to remove the light-sensitive silver salts that were still on the paper. It was necessary to make the paper insensitive to light, keeping only what had been recorded inside the Camera Obscura. This process was called “fixing” the image.

These were the first experiments, the solved problems and the unsolved ones. The calotype, which Talbot soon changed to talbotype (or tabotype) on the advice of friends, reached its maturity and potential for effective use in photography in 1841 when the following points were addressed:

1- Reviewing the role of iodine

Iodine forms silver iodide, but this does not darken with light. Talbot knew this property and even used it as a “fixative”, in the sense that if you replaced the chlorine with iodine in the undarkened, unexposed silver chloride, the clear parts would remain clear. He called silver iodide “dead stuff”. But when he learned that it was precisely the iodine that Daguerre used by smoking it on polished silver, he reconsidered the matter. That’s when he discovered that silver iodide was indeed sensitive to light, it just needed a little push.

2- The need for development

A paper was prepared by impregnating it with solutions of silver nitrate and potassium iodide (in which silver iodide was formed), then, just before exposure, Talbot brushed it with more silver nitrate and gallic acid. After exposure, even if the paper didn’t immediately show the image, it was possible to “develop” the highlights with a new bath in a solution of silver nitrate and gallic acid. There was a latent image that needed to be “developed”. This greatly reduced the exposure time to something like one to two minutes on sunny days. This was the calotype process that he patented in 1841.

3- A real fixative at last

The ways that Talbot initially tried to fix the image were not very effective. Today we know that the baths of sodium chloride, potassium iodide or ammonia that he experimented with, didn’t actually remove the part of the silver salts that hadn’t been developed, they didn’t fix the image. They rather de-sensitized it, but it soon deteriorated. The solution came from Sir John Herschel, who in February 1839, out of curiosity after the announcement of the Daguerreotype, made his own photographic process, in one week according to Helmut Gernsheim, in which he used sodium thiosulphate as a fixative. This actually dissolves the silver halides and fixes the image. It’s the classic fixative, still used today.

The final and complete calotype process presented in 1841

After much experimentation, Talbot finally arrived at something that was fully usable. The process involved:

1- Pure paper, without additives, silver nitrate and potassium iodide to form Silver Iodide, which is sensitive to light but does not darken immediately under its action. This paper can be stored for some time

2- Before exposure, the paper is “activated” with a mixture of silver nitrate, gallic acid and acetic acid.

3- After exposure, the image is not yet visible but needs to be developed in a solution of silver nitrate and gallic acid. The image obtained is “negative” (a term coined by Herschel), i.e. what is light in the scene is dark in the image and vice versa.

4- Wash in clean water. After developing, the paper will be impregnated with silver nitrate and gallic acid, which need to be removed so that they don’t interfere with the fixative.

5- The negative is fixed, i.e. washed in a solution of sodium thiosulphate, which dissolves and removes all the silver iodide that has not been developed and is therefore in the light areas of the negative. At this point, the paper contains only the developed, metallic silver, which forms the dark parts of the image.

6- Finally, the paper just needs to be thoroughly washed and dried.

Obtaining a positive

For the final print, Talbot used the process that had already worked well by contact, the one with which he had been printing silhouettes of botanical species and fabric lace since 1835 and which he called photogenic drawing. This process became known as“salted paper“, which is simply paper bathed in a solution of sodium chloride and then silver nitrate. This is a process that doesn’t require developing, the image is darkened in sunlight, through a glass that presses the negative against the positive. Once exposed, you just need to wash/fix/wash/dry.

It’s important to note that salted paper, although a twin of the calotype negative, gained independence and was widely used with negatives from other processes, such as wet plate or collodion, for example.

After the discovery

The open door – calotype by Fox Talbot – 1844

–

Talbot was very upset to see that in addition to international fame, overnight Daguerre had received a considerable pension for life from the French government, while the English authorities paid little attention to him. It is said that this was the reason that led him to patent the calotype and for some time he closely monitored infringers of his rights. For this reason, his countrymen accused him of delaying the development of photography in England.

The use of paper as a support gave the photographs made using this process an unavoidable texture and loss of detail. The paper was treated with beeswax to make it transparent, but nothing really made it translucent. The defenders of Daguerreotypes always used this point as irrefutable proof of the superiority of the French process, which, on the other hand, seemed to have microscopic perfection.

The advantages of being able to make several copies from the same negative were not immediately apparent. The much lower cost of the calotype, which easily allowed for much larger prints, also didn’t seem so important at the time. In the 1840s, having your picture taken by the invention of the century was sold as a luxury item, accessible only to a clientele that didn’t pay much attention to price.

David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson – source Wikipedia

–

In the early years of photography, the daguerreotype remained a jewel, a unique piece in its small cases full of velvet and gold, and was by far the preferred process for portraits The calotype soon found its place in architecture and landscapes, due to its ease in larger sizes, portability and reproducibility. In the hands of some photographers, it was also used creatively for artistic portraits and genre scenes. The most famous case is that of Scotsmen David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, who worked as a duo. But the scenario changed radically in the 1850s with the discovery of collodion as a support for glass negatives and albumen paper for printing photos.

If you are on the Photographic Processes theme circuit:

In the next room, you will learn about collodion, or wet plate. This is a process that uses glass plates in the camera to produce negatives with details as fine as those of a daguerreotype, but with the reproducibility of a negative/positive process.