Ferrotype or tintype | Hamilton L. Smith

The ferrotype is another development of the use of collodion as a base for suspending silver salts. It uses the same characteristic as the ambrotype in which a black background makes the exposed areas look as highlights and hence generates a direct positive image. The basic difference, compared to the ambrotype, is that the ferrotype, or tintype, uses a black-painted tin plate as a support for the collodion.

Tin is steel covered with a thin layer of tin. Ferrotype refers to the iron in the steel. The advantages of the ferrotype over the ambrotype are many: it costs much less, it is thinner and can be placed in albums or mounted on a simple card, it is light and doesn’t break like glass. However, its appearance is much poorer, it doesn’t have the glass shine and nobility of the ambrotype.

Among the photographers offering ferrotypes were mainly itinerant photographers, from fairs and popular festivals. They were generally street photographers who, for a few bucks, took and delivered the photo to the client in a few minutes.

As price was a determining factor, ferrotypes are generally reduced in size and nowadays are usually very dark. This is because, even at the time they were made, they did not present a pure white. What we judge as highlights, is actually the part that has been exposed and developed, it would be the black area in a negative. But in addition to this initial condition, the ferrotypes were varnished as a mean of protection and, in general, after so many years this varnish has oxidized and darkened the image even more.

This darkening cannot be remedied because the varnish is impregnated in the layer with the silver crystals and it is impossible to remove just this varnish without damaging the under layer.

The patent for the ferrotype process was registered in 1856, five years after Archer published the collodion process. This made the American Hamilton L. Smith a kind of its official inventor, but it is known that, for example, the Frenchman Adolphe-Alexandre Martin had already described the process in 1853.

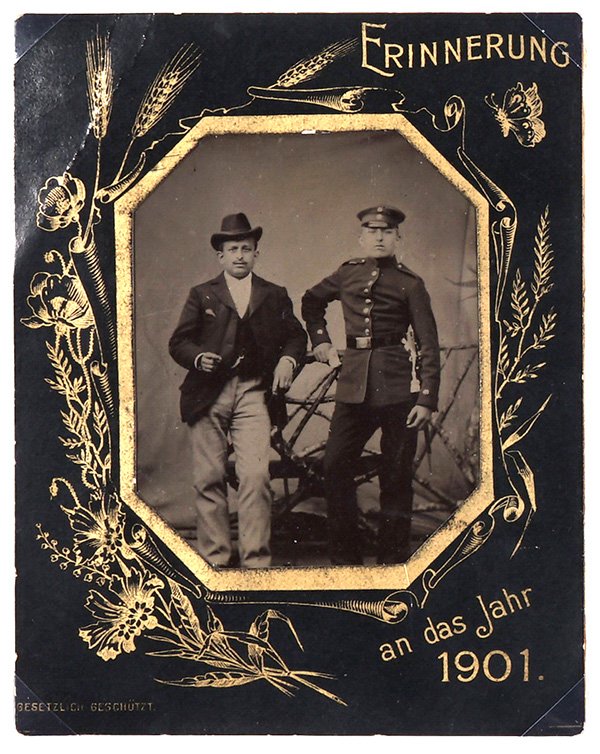

Like other processes using collodion, the Ferrotype went virtually extinct with the introduction of dry gelatine plates. But precisely because it had an almost marginal side, practiced by street photographers, it continued to be offered at tourist attractions and popular festivals. The ferrotype that opens this article, for example, Erinnerung an das jahr 1901, Remembrance of the year 1901, is already a very late ferrotype.

If you are on the Photographic Processes theme circuit:

The chemistry of silver and its halides in the production of light-sensitive salts was already well known in the 1870s. What was really missing was the ideal suspension medium. That was the gelatin revolution. It was gelatin that made modern photography possible.