Praktica | VEB Pentacon

The Praktica was a camera that played an important role in the history of photography. It was known, like the Pentax K1000, as the student’s camera. It was affordable, reliable, fully manual and therefore very popular with photography beginners.

If you look at the specifications of most of the SLRs (Single Lens Reflex) that were successful from the 1960s onwards, the uniformity of the basic controls is impressive. Almost all of them have a curtain shutter that goes from 1 s to 1/1000 s, an optic that focuses to approximately half a meter and offers apertures from f/1.4 to f/3.5 with the normal 50mm lens, automatic frame counter, flash shoe and sync at a maximum of 1/60s.

The differences were more in the “system” they offered in accessories and especially optics. It’s also undeniable that durability, finish and the level of engineering that translates into firm yet smooth adjustments, that typical sound that assures us that everything inside is working comfortably and precisely, are almost intangible qualities that make the difference between premium brands and others.

The Prakticas were on the threshold between the two categories. It was a great entry-level camera, for starting out in the hobby or even a few professional jobs, and then moving on to something more up scale. As even the position of the controls was somewhat standard, migration was very easy.

Genealogy

The first monoreflex camera using 35mm film to establish itself on the market was the Kine Exakta from Ihagee in Dresden, launched at the Leipzig fair in March 1936. It was a camera, or rather a complete system, very sophisticated and aimed at a premium market.

Taking a different approach, in 1939, Siegfried Böhm, who worked at Kamera-Werke (KW), which manufactured the nice Patent-Etui, an extremely well-built folding camera, but from an earlier generation, as it was launched in 1920, created the Praktiflex, the second monoreflex for 35 mm film to make history.

The concept of the Praktiflex was that of a camera for the amateur photographer. If the Exakta was the choice of the scientist or the professional, the Praktiflex was aimed at the public for family snapshots and outings without too much commitment. But since Patent-Etui, KW’s philosophy had been one of intelligent construction and high quality. This was fully transferred to Praktiflex.

The Praktica was the 1949 reissue of the Praktiflex. It kept the basic architecture of the body but adopted the M42 thread standard that would become the first inter-brand lens x camera coupling system. Although it is common today to refer to the M42 mount as a Pentax system, the Japanese firm only adopted the standard 10 years later in 1959. The M42 was launched by VEB Zeiss Ikon and Kamera-Werke (KW) in 1949 to equip the SLR Contax S and Praktica, respectively.

Post-war in the German photographic industry

But to understand how the KW project ended up at Pentacon, we need to consider what the division of East and West Germany meant.

The heart of the German photographic industry was in Dresden. There had long been a constellation of companies manufacturing cameras, optics and also those specializing in individual parts, such as shutters, which were integrated into complete projects. It so happened that Dresden remained in East Germany and all these manufacturers were nationalized and came to form the giant VEB Pentacon, where VEB comes from Volkseigener Betrieb, which would simply be State or People’s Company, and Pentacon came from the combination of Pentaprism and Contax.

But this consolidation of industry took place in stages. In 1959: several Dresden companies (including KW and Zeiss Ikon) were brought together under the name Kamera-und-Kinowerke Dresden. It wasn’t until 1964 that this entity was officially named VEB Pentacon.

In the new organization, Pentacon was responsible for the bodies and cameras and Carl Zeiss Jena supplied the lenses. Until 1953, the Jena optics were still exported to equip cameras such as Rolleiflex and others on the Western side, but from this point on sales to the “other side” were stopped and all production channeled towards exports already in Pentacon VEB cameras or at least in the M42 standard.

Although the M42 assembly made Carl Zeiss Jena lenses world-famous and accessible to millions of people, it was also a strategic trap. The state’s demand for millions of “affordable Zeiss” lenses for Praktica cameras prevented the company from evolving into the high-tech superpower it could have become in a free market, where the interests of an optical industry would not necessarily be tied to a single camera manufacturer.

There was also a dispute over the Zeiss name and several products from Jena were sold simply as “aus Jena” and also using single letters such as “B”, “S”, “T” were references to Biotar, Sonnar, or Tessar. At the end of the litigation, the West German side, Carl Zeiss Oberkochen, retained the international right to use these trademarks.

New technologies

In the midst of so much political and governance turmoil, research and development laboratories have not remained dormant and some very interesting things have been incorporated into the Praktica series.

Pentaprism for non-inverted vision

It would probably have been impossible for monoreflexes to win out over range-finders with a waist level finder. After Leica, framing the scene through a viewfinder at eye level became indispensable in many branches of photography, especially journalism, which was growing and reformulating rapidly into a more image oriented trend .

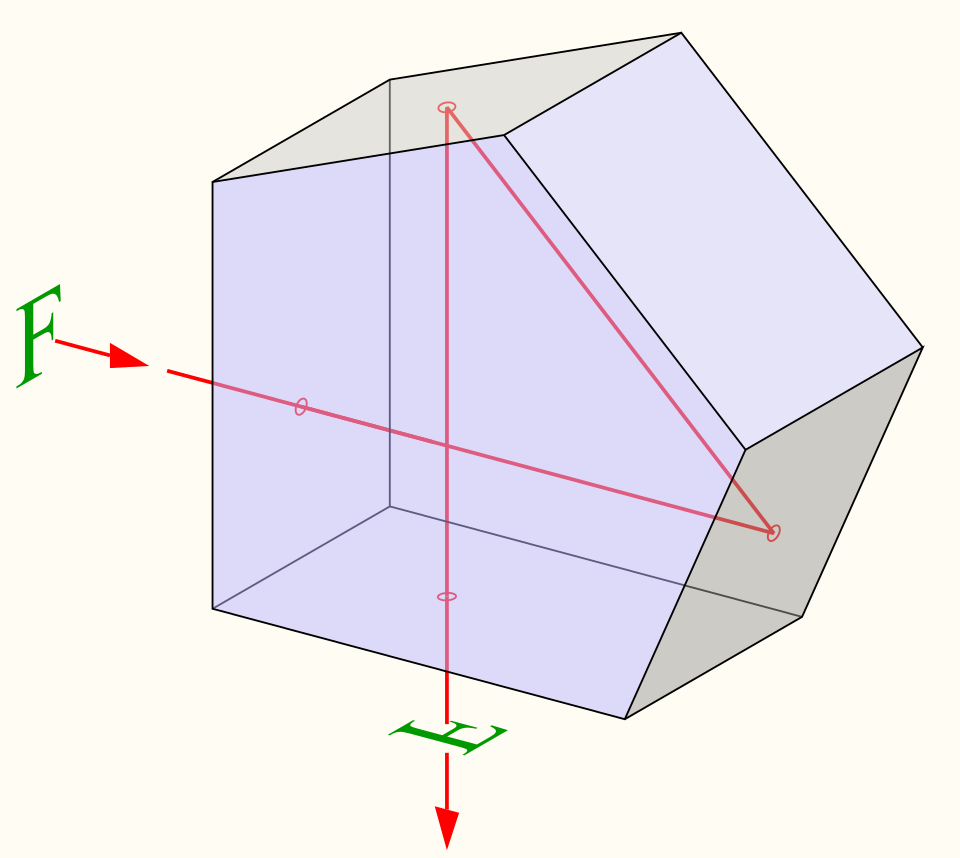

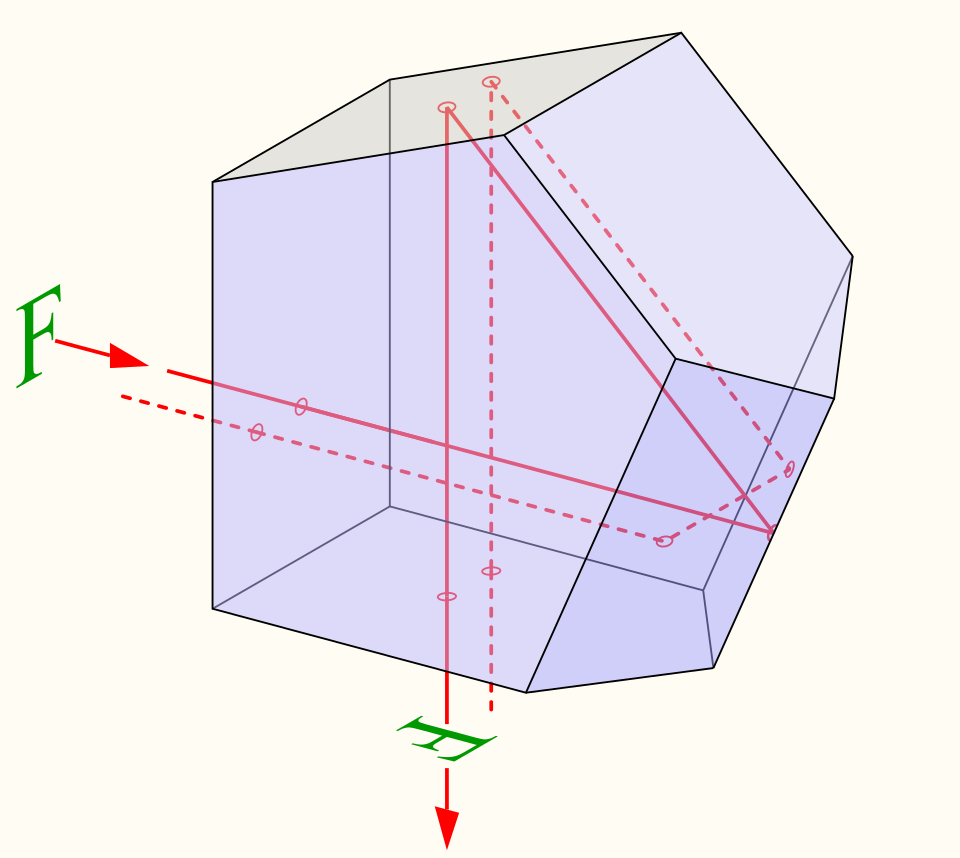

It wasn’t even just a question of seeing at eye level. The inverted right vs. left image that the mirror produces on the small ground glass of the first SLRs for 35 mm film is difficult to get used to and a huge barrier for beginners. The image needs to be inverted again in order to be seen by the viewfinder as if it were just peeking through a hole.

source: wikipedia

Because of these two factors, the pentaprism was instrumental in the widespread acceptance of the single lens reflex or SLR concept. The first camera to be equipped with a pentaprism was the Contax S, which was developed by Zeiss Ikon in Dresden in 1949. Then, as they were consolidated into a state-owned conglomerate, the Praktica FX also gained its prism in 1952, at first as an accessory, and from 1964 it was incorporated into the Praktica V camera body.

The optical principle of the pentaprism had been known for a long time. Strictly speaking, it wasn’t something that could easily be patented. There was also the post-war issue and the difficulty of forcing a recognition of rights for East Germany. What really gave Zeiss Ikon in Dresden a competitive edge was the difficulty of manufacturing the small glass block without leaving a vertical stripe in the middle of the image. But it was a small head start. The concept was soon perceived as mandatory for SLRs and all manufacturers quickly incorporated it.

Mounting on M42

The totalitarian and totalizing spirit of the new state administration in East Germany bore at least one fruit in terms of the rationalization and universalization of certain parameters that could have remained isolated and differentiated in various manufacturers. This is how Zeiss Ikon’s Contax S and KW’s Praktica were launched in 1949 sharing the same mount for their optics known as the M42, which is nothing more than a 42 mm diameter thread.

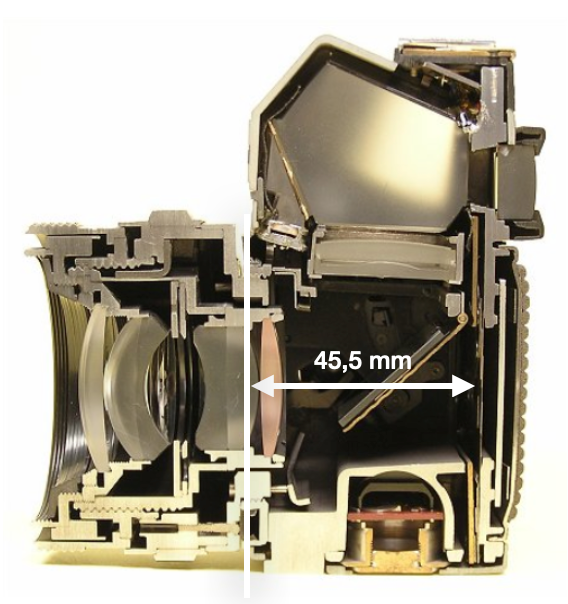

Of course, this was only possible because, in addition to the thread itself, the distance from the flange stop to the film was standardized. This was set at 45.5 mm. This is enough distance to accommodate the mirror, which is at 45º when the viewfinder is open but which must pivot and allow the image to pass through at the moment of the click.

The standard was widely adopted and allowed bodies and optics from completely different sources to be mixed. Here’s a list of the main manufacturers that have launched cameras with the M42 lens mount standard:

1. Asahi Optical Co.(Pentax – Japan): Pentax used the M42 mount from its first Pentax models (1957) through to its hugely successful **Spotmatic** series (from 1964), until it introduced the K mount in 1975. Pentax’s global success contributed significantly to the popularity of the mount, which was often referred to as the “Pentax screw mount”.

2. KMZ(Zenit – Soviet Union): After initially using the M39 mount, KMZ switched its popular **Zenit** SLR line to the M42 mount (starting mainly with the Zenit-E around 1965), producing millions of cameras with this mount.

3. Yashica (Japan): Produced several well-regarded M42 SLR cameras in the 1960s and early 1970s (such as the Pentamatic II, TL Super, TL Electro X).

4. Fuji Photo Film (Fujica – Japan): Offered a successful line of M42 SLRs, particularly the ST series (such as the ST701, ST801, ST901) in the 1970s.

5. Cosina (Japan): Manufactured M42 cameras both under its own brand and for many other brands (e.g. Vivitar, Chinon).

6. Ricoh (Japan): Also produced M42 SLR cameras (such as some Singlex models) before developing its own mounts.

7. Chinon (Japan): Made the SLR M42s popular before switching to other mounts.

8. Voigtländer (West Germany): Even Voigtländer adopted it briefly for its Icarex 35S TM and later SL706 models (after the merger/collaboration with Zeiss Ikon).

The Praktica Shutter

Here Praktica really broke new ground and was even ahead of some prestigious competitors. Leica, since 1925, had established a standard focal plane shutter that runs horizontally with two curtains over the 24x36mm window on 35mm film. The first opens the frame and the second closes it. At the fastest speeds, the second curtain begins to close when the first has not even opened the frame fully.

The idea of a focal plane shutter using rigid metal blades was already known in Japan. The Konica F was the first 35mm film camera to use a system it called Hi-Synchro, back in 1960. Copal, which also manufactured leaf shutters, developed another type called Copal Square that used parallel arms to move the thin blades that acted as a curtain.

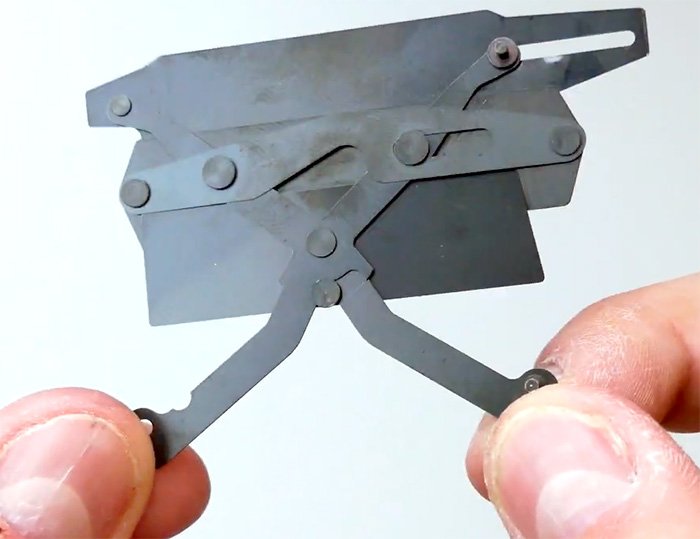

In the Praktica L-series (introduced in 1969). The “L” stands for Lamellar, in reference to the steel blades. It was an independent East German development, patented in 1961 by engineers Horst Strehle, Günter Heerklotz, and Hans Zimmet. The idea was to use a scissor design to expand or retract a set of 3 or 4 blades.

These images are frames from a very interesting video in which a Praktica is completely disassembled:

Praktica MTL-3 camera teardown

With this configuration, one curtain remains covering the frame. When the release button is acted, it is retracted, opening the frame, and then a second curtain begins to close, performing the reverse movement: it was retracted and begins to expand. This second curtain leaves with the appropriate delay to produce the selected exposure time, between 1 and 1/1000 s in the case of the Prakticas.

The mechanism is much noisier than traditional cloth curtains, but it has much greater durability and the main advantage is that it allows a flash sync speed of up to 1/125 s against the normal 1/60 of fabric curtain shutters. This becomes especially interesting when the flash is used in “fill” mode, to soften shadows in an outdoor scene with daylight. When the ISO was as high as 400 without push development, the flash was used much more than it is today. Being able to synchronize at a higher speed was a big advantage.

The shutters of the most sophisticated digital cameras are direct descendants of Praktica’s Lamellar shutter. Instead of steel, carbon fiber is used which, being lighter, offers less inertia when braking and can therefore be accelerated to higher speeds. This is a very honorable historical distinction for an “amateur” camera, as was the concept Pentacon had chosen for its Praktica line.

Anti-reflective treatment

This was another asset developed first-hand by Carl Zeiss Jena and which cemented its reputation for excellence in optics. Although competitors soon implemented the technology, the brand’s image gains and prestige last to this day when, 90 years later, Sony lenses demand a premium price and bear the Zeiss T*.

In 1935, Alexander Smakula, a Ukrainian physicist working for Carl Zeiss Jena, invented a way of applying a microscopic layer of magnesium fluoride to the surface of glass in a vacuum. By an interference effect of the portion that reflected off the glass and the portion that reflected off the magnesium fluoride layer, much more light was transmitted on its way through the lens.

Before 1935, whenever light passed from air to glass (or from glass to air), around 4% to 6% of that light was reflected. This may not sound like much. But in a simple lens like a Tessar (4 elements), around 25% of the light was lost. In a complex lens like a Planar (6 elements), the loss is almost 50%.

Worse than the loss of light was the reflection: the reflected light bounced off the lens, scattering randomly, eliminating contrast and creating “ghost” images.

But the invention was kept as a military secret and only binoculars, periscopes and other equipment used during the war could undergo the anti-reflection treatment. Once the war was over, the Carl Zeiss Jena lenses began to show that slight bluish tint and produce a contrast never seen before. The colors became more saturated and the blacks deeper. These were the lenses that bore the mark T, for Transparenz, in German. In 1972 the T became T* to indicate that the lenses now had not just one layer but several layers of salts and metal oxides to act on a wider range of wavelengths or colors of light.

The Praktica MTL3 from the collection

The L series was launched at the end of the 1960s. Its main attributes were a light meter with through-the-lens reading and, most importantly, the shutter with steel blades running vertically, as described above.

Photometry went through several stages of improvement. At first it was just an independent light meter on the top of the camera, then it was coupled to the ISO and shutter speed, but the iris had to be closed to get the reading. To do this, with the scene composed in the viewfinder, one has to press a lever next to the lens. The image darkens according to the f stop that is selected and a needle indicates whether the light is sufficient or not. This is the MTL3 method.

The light meter itself, like all those that measure light through the lens itself, needs a battery, which unfortunately was a 1.35V mercury battery, the PX625. You could even use a 1.5V alkaline battery of the same size. But the problem is that while the mercury ones kept the 1.35V for their entire life, the alkaline ones have a voltage that drops and alters the readings. Ideally, you should have an adapter with electronics so that even when the alkaline varies, it always delivers the same voltage. There are some available under the MR9 code.

The L series was extensive: L, LB, LTL, LTL3, MTL3, MTL5, MTL5B, MTL50, LLC / PLC / VLC, and even had wide-open photometry. The next step was the Praktica B, which incorporated electronic shutter control and a bayonet.

A slightly odd point about the Prakticas is the position of the shutter button, which is not on the top of the camera but angled to the side of the lens. This is also the case with the Kodak Retina Reflex. It’s more ergonomic on top of the camera, but after a few shots you can get used to it.

When it comes to loading new film, the coupling is very secure. Overall, it’s a well-designed camera with a robust construction.

Lenses

Lenses for the Prakticas were at their peak of variety and specification in 1978 when the MTL3 was launched. They were labeled Pentacon or Carl Zeiss Jena. Many of them had electronic contacts so that they could be used with the LLC/PLC series cameras, which allowed wide-open photometry. But they worked normally with mechanical cameras such as the MTL3. They also had an anti-reflective multi-coating treatment, sometimes indicated as MC.

An interesting point about the MTL3 is the versatility of its “Stopped-down” metering system (the little lever you press next to the shutter button). This meant that it didn’t matter whether the lens had “electric” pins or not – it worked with every M42 lens ever made, from the Zeiss Biotars of 1949 to the Takumars (Pentax) of the 1980s. This “universal” compatibility is what makes the MTL3 an even more desirable tool than the models with full-open lens photometry.

The standard lens was the Pentacon 50mm f/1.8 (pictured above). It was a 6-element design known for its incredible close focus capability (up to 0.33 m), making it almost a “semi-macro” lens. Still in the standard 50mm lens category, there was also the Carl Zeiss Jena Tessar f/2.8: Known as the “Eagle Eye”, this was the economical, ultra-sharp 4-element option.

The most popular wide angle was the 29 mm f/2.8 (pictured above). An odd focal length when 28 mm was standard on many other brands. For longer focal length: Pentacon 135 mm f/2.8: Often called the “Bokeh Monster” due to its 15-blade aperture in earlier versions (although in the MTL3 era, it usually had 6 or 8 blades). It remains a favorite of portrait photographers to this day.

A very interesting lens to own is the Carl Zeiss Jena Pancolar. It was launched as a reaction to the Japanese and with the mission of surpassing the old Biotar 58 mm f/2. It was aimed at professionals and demanding enthusiasts who were looking for high central sharpness, even at wide apertures, along with better color correction for the newly popular color films.

These were the most basic. In addition, for professionals and demanding amateurs, some big names such as Sonnar or Flektogon were also on offer.

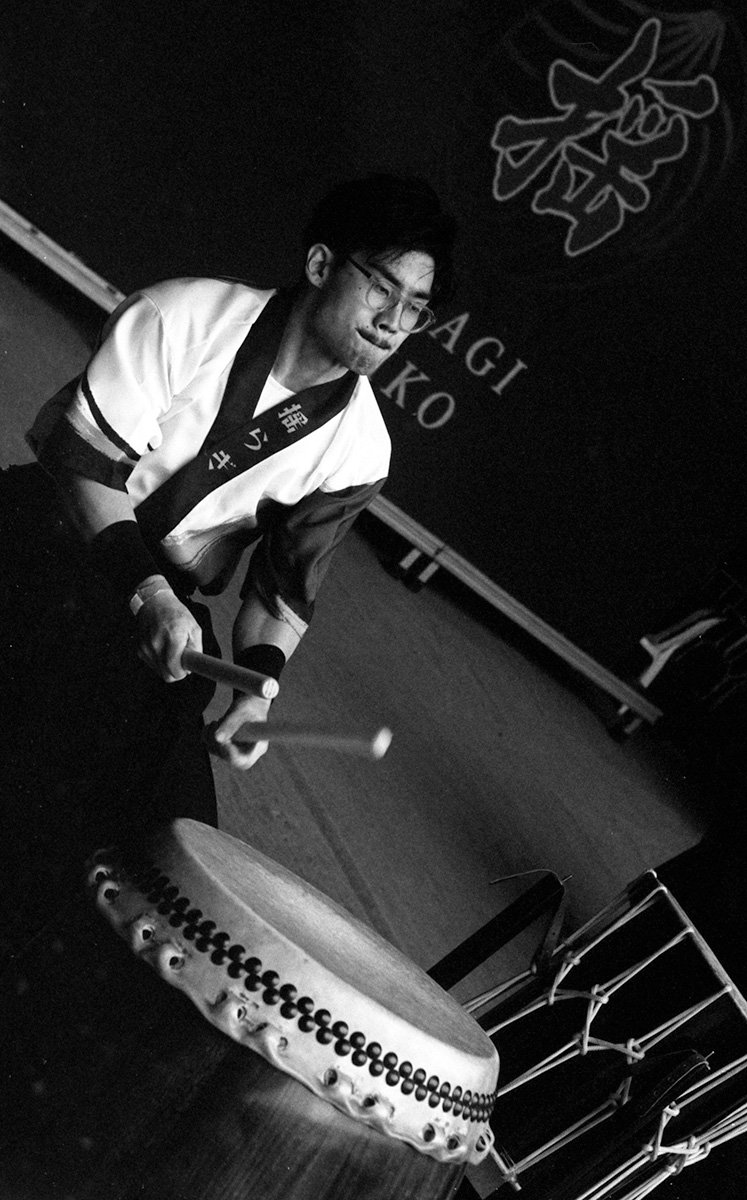

Very interesting with these screw cameras are the hybrid options. For example, one can use a Meyer Görlitz Trioplan 100mm f/2.8. This is very soft when wide open and provides portraits with a dreamlike atmosphere. But you need a subject that gives room to dream. Otherwise it’s just a bit blurry. For example, below are some photos I took at a Taiko performance. The first photo I think the Trioplan went well with the girl’s pensive gaze. In the second, I think a harder lens would go better with the same girl in action.