The Invention of Photography and Modernity

Although the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries can be considered the birth of modern science, when names such as Galileo Galilei (1564-1642), Isaac Newton (1642-1727), Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), Francis Bacon (1561-1626) and René Descartes (1596-1650) laid their foundations and methods, the use of scientific knowledge to generate technologies would only really expand more than two hundred years after this period. These gentlemen were much more concerned with unraveling the mysteries of the universe than with the possible practical applications of their theories.

Photography, which officially came into being in 1839, falls squarely within this pattern. The basics of the behavior of light and its influence on certain substances had been known for a long time. The reason for this delay, this long gestation, goes far beyond technical difficulties or lack of knowledge of the physical/chemical principles in question. For photography to be born, a change in mentality, in the way we look at life and even our role here in this world, was necessary. This is the subject of this article in which I will try to explore the motivations and reasons for the immediate success of the mechanical images produced by photography.

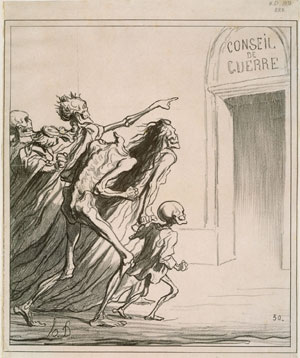

What was at stake was a certain disenchantment of the world with a redefinition of the religious, the shift from hereditary monarchies to republics and elections, from the agrarian system to the industrial one, from the aristocratic ideals of honor and descent to the valorization of work as a means of enrichment and social ascension, in short, the whole package of Modernity brought about by the Enlightenment or the Bourgeois Revolution, which are alternative names for the same set of transformations seen from one angle or another.

Images for what?

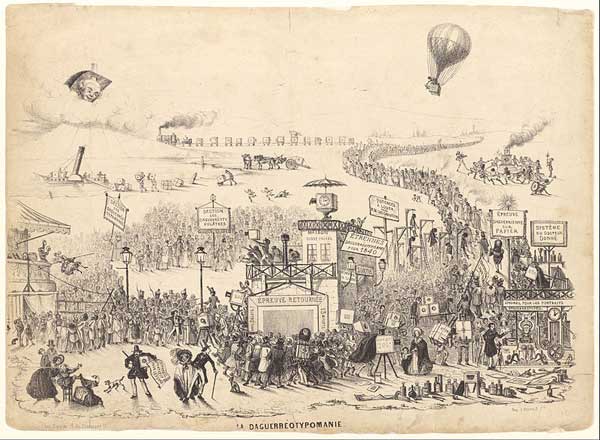

Image production has never been anything like the war industry, in which, unfortunately, humanity has always sought constant improvement. On the contrary, images have often not aroused any interest and in other cases have even been banned throughout history. When images started to become important in our culture, they were left to artisans and artists in manual processes. It seems that there was no interest in a process like photography until the 19th century and suddenly it became a necessity. A frenzy ensued over who would be the first to discover a suitable way of rendering optical images onto a permanent medium. It’s often said about problem-solving that the trick is not just to find the answers, but to ask the right questions. Photography is an exception to this rule, as everyone was well aware of what they were looking for, what the question was. All the effort went into finding the answer.

Was the 19th century poorly served in terms of images? Were there gaps in the supply of images to be filled? This is questionable in many ways. Today, hardly anyone knows how to draw anymore and drawing, in order to represent something, takes a distant second place behind photography. Even contemporary visual artists often can’t draw. But in the 18th or 19th centuries, drawing was commonplace. There was a need for an army of artists for all sorts of decorated objects, walls, furniture, utensils, etc, with complex ornaments featuring flowers, animals, landscapes, angels, saints… most of that manually done in an array of techniques. Also educated people learned the basics of drawing and painting and used it to take visual notes, just like we take pictures with our cell phones. It was the same with music; playing musical instruments was as common as singing in the shower today. These were talents that guarantee the revenues of many workers and was also, as part of a good education, a sign of refinement.

If we consider now painting for the art market, at the time photography was created, being an artist was a regular profession mainly embraced by young people from middle- to low-income families. The path and its milestones were very clear. In the case of France, it began with being admitted to a public or private studio as a student and/or to an École de Beaux Arts – also made up of studios run by confirmed artists. Those who came from the countryside would usually first go through drawing courses in municipal schools, offered free of charge, before or after working hours in morning or evening courses. Most artists had a second job to provide them with a regular and reliable income that they couldn’t guarantee as artists. At the highest level, someone would become a history painter and receive official commissions for large canvases. This would certainly create opportunities to sell portraits to aristocrats and the upper bourgeoisie.

Anne Martin-Fugier, in her book “La vie d’artiste au XIXe siècle“, gives an insight into what success meant: “A confirmed portrait painter could make a lot of money. Around 1845, a portrait painted by an artist with a good reputation (Alexis-Joseph Pégignon, Henri Scheffer or Sébastien Cornu) would earn 1500 francs and a portrait painted by a star like Horace Vernet or Court, 3000 francs, that’s more than the annual income of a petty-bourgeois family.” At the same time, Martin-Fugier also comments that Ingres’ wife once reported, speaking to young artists, that during his stay in Florence, Ingres (he was about thirty) drew a series of portraits for the Gonin family at a price of 25 francs each. Another interesting fact is that, after the 1845 Salon, of the 2079 works of art, including paintings, drawings and miniatures, that were on display, 700 portraits went into private hands, 250 were bought by the state and 150 went to Versailles. The rest were returned to the artists or sold for 10 to 12 francs each and exported to Russia, Germany, England and the United States.

Price and supply were no barrier to those who wanted to own images for decoration or to immortalize their figures. There were prices and artists to suit all budgets. The Prix de Rome was a four-year scholarship that was, for a long time, the ticket to a successful career. However, among the thousands of students dreaming of and competing for this coveted prize, only a handful would get the chance. Among those who didn’t, many were talented enough to paint or draw portraits and established themselves in the business. There was even a category of portraits called “miniatures” that were initially reserved for the aristocracy and the upper bourgeoisie, and after the French Revolution, artists who lost a significant part of their clientele, who fled or went to the guillotine, began to offer better prices and miniatures entered a more financially tight social stratum. These are small paintings, usually watercolors or gouaches on ivory, measuring around 5 x 7 cm, preserved in metal frames or small boxes. Daguerreotypes practically put an end to miniatures. In terms of their use, both address the same need to offer a faithful image of oneself or a loved one. The sizes, posture, framing and manual coloring of daguerreotypes, as well as the difficulties in producing large plates, certainly had their ancestry in miniatures.

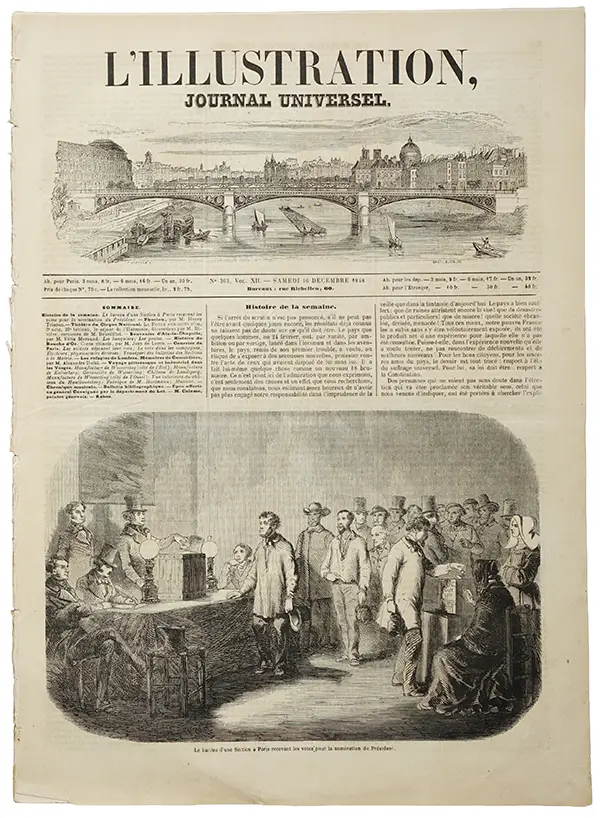

If we now consider the printing techniques, aimed at large quantities, we have several options presented mainly from the end of the Middle Ages. Xylography (~ 1400), Metal engraving with burin (~ 1430), Metal engraving with mordant (~ 1530), Aquatint (1650), Mezzotint (~ 1670), Lithography (1796) (these dates are taken from the Met Museum website). The subjects were mainly important figures of their time, historical events, genre or still life, often carrying a moral background, and thousands of copies of works of art. Prints were extremely important as a dissemination medium for works of art and were also a way of owning a reference from a master for a low price. Mezzotints were suitable and very popular for copies of oil paintings. As we enter the 19th century, we see the expansion of the press into newspapers, magazines and other periodicals, which began to break new ground and shape what would become a mass media image in all its variants, such as caricature and humor, which were much in demand. With techniques that could produce thousands of prints from the same matrix (lithography, for example), printed images became ubiquitous.

One of the first newspapers to make extensive use of images in its stories.

Launched in March 1843

–

Thinking now about photography purely from the point of view of its virtues and flaws, it may seem strange what a notorious place it almost instantly gained. Why not just another method among others for image making? If we consider its limitations in size, without colors, with complex and expensive procedures and prone to failures as it was in the beginning, it is quite remarkable that it was immediately acclaimed as one of the most importante inventions of the century. On the plus side, it was very detailed and quick to produce. We’ll come back to that later. But the success was tremendous, for example, in the preface to Traité de Photographie, fourth edition of June 1843, Lerebours (a manufacturer of lenses and equipment for daguerreotypes and also an important photographer himself) says that all 1800 units of the previous edition were sold in just two months.

The daguerreotypomanie became the talk of the town. Although only the basic equipment cost around 400 francs in France, many photographic studios were opened overnight and a movement of itinerant photographers began to spread to all corners of Europe and also the United States. In Le Nouveliste of August 25, 1853, the journalist, visibly irritated, talks about the fashion for the new technique: “The making of daguerreotypes requires neither intelligence, nor spirit, nor art, nor studies, nor work, nor investment, Paris is invaded by daguerreotype painters. We count them by the hundreds. The daguerreotype ended the tradition of miniatures, and more than one talented miniaturist was forced to throw away his palette to practice the daguerreotype, a horror. Now that everyone can have their likeness for five, three and even two francs, the oil portrait has fallen into oblivion.”

Far from the big cities, the daguerreotype had to face a clientele that was not so enthusiastic or inclined to perceive the intangible values on which a new fashion usually rests. The testimony of John Werge, himself a daguerreotypist, about the arrival of an itinerant photographer in his town when he was still a teenager is interesting: “Some time after that [referring to the first time he saw a daguerreotype in the window of the Post Office] a Miss Wigley, from London, came to town to practice Daguerretyping, but she did not stay long and did not, I think, make a profitable visit. The opposite could hardly be imagined, as the images from that period, taken in the sun, with blinding reflections and distortions of the human face, would impress few people about the process or the newest wonder of the world. In that early period of photography, the plates were so insensitive, the sessions too long and the conditions terrible. It was not easy to persuade anyone to submit to the ordeal of sitting down or paying the sum of twenty-one shillings for a very small and unsatisfactory portrait.”(The evolution of photography – 1890 – John Werge p31).

Among the “terrible conditions” to which Werge refers is, for example, staying still for 10 or more minutes in direct sunlight. Many photographers advised their clients to keep their eyes closed in order to endure the situation without moving. The pupils were added later by drawing them on the plate.

It’s worth wondering why daguerreotypes gained such popularity even before some very basic improvements were implemented, light sensitivity probably being the most important of these. The handy explanation is to say that it provided a faithful image, truly identical to the person photographed as no other medium could. This is possibly true. At the same time, resemblance is not always a good strategy in portraiture. “The most terrible enemy that the daguerreotype has had to deal with is undoubtedly human vanity. When someone is portrayed by traditional means, the obedient hand of an artist knows how to soften the rather severe features of the physiognomy, to improve the attitude and rigidity, giving it grace and dignity. Not so with the photographic artist, unable to correct the imperfections of nature, his portraits are unfortunately guilty of being too similar, they are, in a sense, permanent mirrors in which self-esteem does not always find its consolation”. J.Thierry in Daguerreotypie of 1847 (p.137).

Even if we accept that likeness was the key to the huge success of the daguerreotype, or the success of photography as a whole, in the sense that it achieved something that painting couldn’t, we have to be careful. Verisimilitude is a very complicated concept. I agree with those who defend the verisimilitude of photography as its main success factor. But as long as we take this verisimilitude as something contaminated by subjectivism, cultural environment and conventions. So, we can say yes, although likeness is not something objective, definable, but rather quite questionable, it is probably true that people in the 19th century considered daguerreotypes to be very faithful representations of those portrayed, something more than a realist painter, like Courbet, or a classicist, like Ingres, could achieve in this direction.

The long-running discussion, of which the conflict between Classicism and Realism is just one of many, revolves around what is meant by “real” – is the immanent more real than the transcendent? This is a question whose solution is not as obvious as it might seem. Once we agree on this, the next question automatically becomes: why did they considered that photography presented life like images as no other technique or artist could? I propose that this is the right question to investigate.

But before addressing this crucial point, it might be a valuable exercise to remember how reality, which we can assume to be unique, has always had multiple renderings, all of them very true to their contemporary viewers. Every culture that has adopted the pursuit of realism as a goal has achieved it to its complete satisfaction. Giotto di Bondone (1266/7 – 1337), painter of the frescoes in Italy, had his saints and other figures considered by his contemporaries to be as realistic as living people.

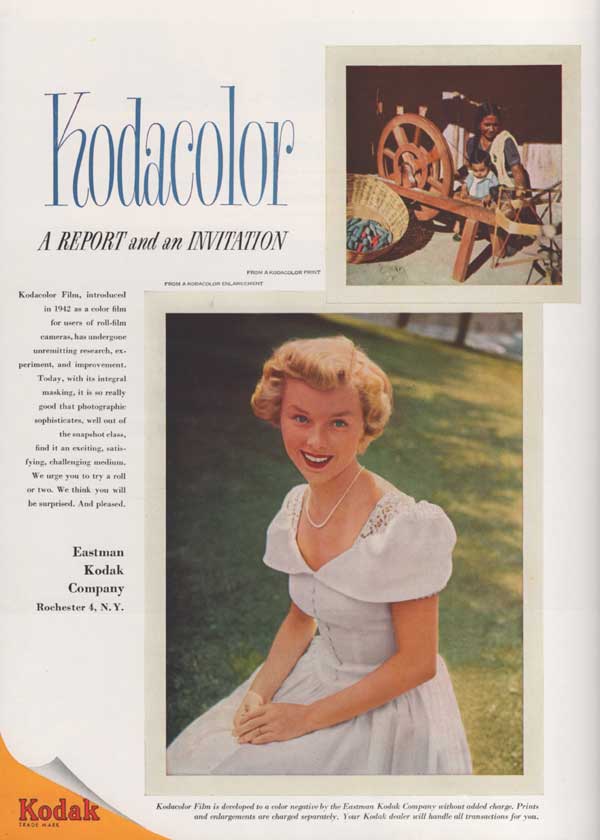

Even looking back at more than 170 years of official photographic history, we know that daguerreotypes were considered faithful images, perfect representations of their subjects or landscapes. We can hardly share the same opinion today. When color film became a popular product, our ancestors became accustomed to a specific way of representing reality according to what the photos showed and what seemed true to them. It was something like the photo above, from a Kodak ad in U.S.Camera from 1951, which for us is absolutely dated, flat and would need a lot of corrections in terms of verisimilitude. Perhaps, on the image below, a contemporary Canon advertisement, we can finally say that now yes, now we’ve done it! This is absolutely like reality.

This problem of understanding what may or may not work as a faithful representation involves partly the psychology of perception and partly the philosophy of language. It is the central issue in Ernst Gombrich’s classic Art and Illusion. The key concept he develops is that resemblance is something that, within very flexible limits, we don’t just judge with our eyes, it’s a matter of learning and then matching what we see with what we learnt.

It is the method and not the image itself that legitimizes the verisimilitude of the photograph

The people looking at the first photographs weren’t checking the fidelity of the images against their actual visual impression. They were learning what a faithful image had to look like. Whatever result a photograph presented, no matter how crude, how lifeless, how compressed in tonal scale, how far from the colorful real world, they would call it a true representation of reality. Photography, a 19th century concept, was born to be, by definition, by concept, a faithful representation of the world around us, because it is nature, light, the object that represents itself. It is the method and not the image alone that legitimizes the verisimilitude of photography.

They didn’t know or didn’t want to?

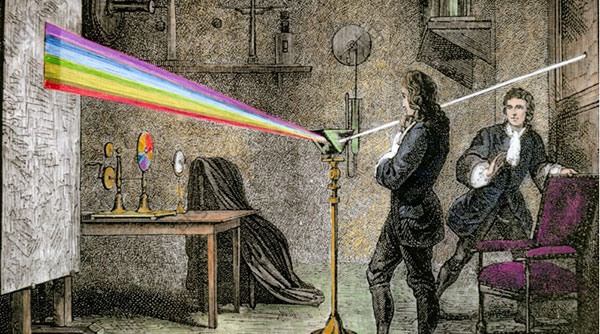

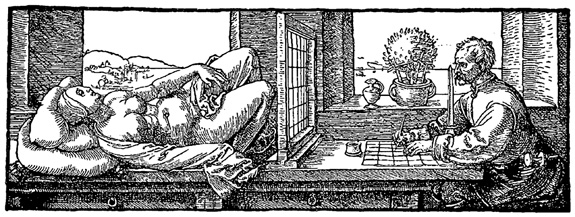

One aspect that several historians have drawn attention to in the development of photography is the delay between the discovery of its basic principles and its final invention as a process for creating images. In this regard, a long quotation from John Werge in his The evolution of Photography published in 1890 is worth mentioning: “More than three hundred years have elapsed since the influence and actinism of light on silver chloride was observed by the alchemists of the sixteenth century [1556, according to Robertu Hunt, p5]. This discovery was undoubtedly the first thing that suggested to the minds of chemists and men of science the possibility of obtaining images of solid bodies on a flat surface previously coated with a silver salt by means of the sun’s rays, but the alchemists were too absorbed in their futile efforts to convert base metals into precious ones to take advantage of the clue and so missed the opportunity to transform the silver compounds with which they were familiar into the mine of wealth that it eventually became in the 19th century. Interestingly, a mechanical invention from the same period was later employed, with a very insignificant modification, for the production of the first photographic images. This was the camera obscura invented by Roger Bacon in 1297, and improved by a doctor in Padua, Giovanni Baptista Porta, in around 1500, and then remodeled by Sir Isaac Newton.” In fact, the photochemical transformation of silver chloride and the camera obscura had been known since the 16th century. Apparently, it didn’t occur to anyone to combine the two and create photography almost 300 years before Niépce and his contemporaries.

The point is that even for technologies, it takes more than knowledge to materialize them into meaningful discoveries and new habits. The birth of photography depended on lenses and chemical processes, but it also depended on a new attitude towards nature. This was the transformation wrought by the Enlightenment, which brought with it Modern Science. Nature, in this new vision, although considered to be the work of God, lost its mystery, it ceased to be a field of manifestation of a capricious and operative God, closed to any inspection or predictability, but instead as something only material, only existing, governed by fixed and accessible laws. This disenchantment was a long and painful process, which began somewhere in the Middle Ages and never fully took place.

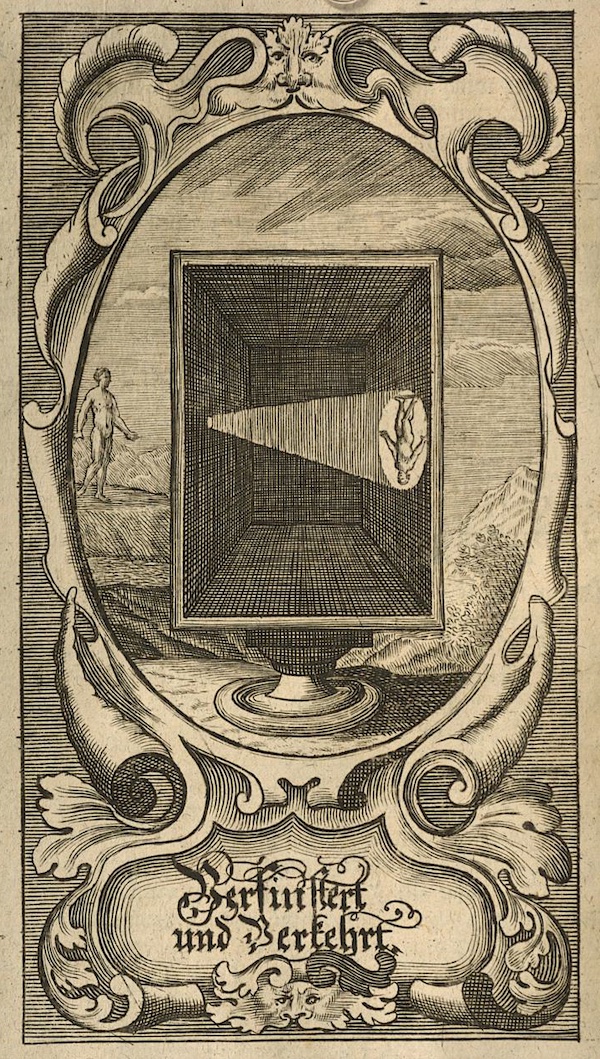

It is very difficult for us today, even for religious people, to imagine the relationship and interpretation that our ancestors gave to natural phenomena, or to the most banal things they observed in everyday life. The illustration above is from a book called Wahres Christentum (True Christianity), written by the very influential Protestant theologian Johan Arndt (1555 – 1621). In chapter II he talks about Adam’s fall and apostasy and how we all inherit his evil essence by blood. He invites us to observe how already in a newborn, yes, in a little baby, this corrupt nature reveals itself in self-will and disobedience, testimonies of the dark root from which it comes: from sin. In the same chapter, he decides to use the Camera Obscura as an example of a typical manifestation of evil. He describes it in the following terms. “Here is shown the so-called Camera Obscura, which is when in a room completely sealed off except for a hole, a certain glass is placed in front of this hole. Then it turns out that people passing in the street can be seen in this room. But in such a way that they walk upside down. This indicates that the human being, unfortunately, in complete darkness, of heart and mind, has fallen into sin, has in fact become a perverted image, from the image of God has become an image of the devil.”

In a world where everything was enchanted, everything was a manifestation of an inscrutable divine will, a world where anything could happen without any predictability, the fact that when light crossed the lens of the Camera Obscura the rays coming from below would obviously project onto the top of the image, showing people upside down, the fact that this was more than logical, natural, observable, without any moral or religious implications or importance… it wasn’t even considered. In the first place, everything had a symbolic religious implication. Our reflex, so natural today, to examine, investigate, understand and seek a natural explanation, didn’t exist yet. The role that a “natural explanation” plays for us today had for them the “symbolic interpretation of some relationship between the observed fact and the sacred scriptures brought by some religious authority”.

As much as Renaissance artists were involved in seeking a naturalistic representation in their images, there was no climate for something like photography to be imagined as a possibility. The act of painting was an act of devotion and the idea was not to be easy. The artist’s talent, effort and mastery attested to his commitment to the sacred. Mechanically recording the image of the Camera Obscura would certainly be a cheap trick, a farce or an act of witchcraft.

Perhaps because of so many centuries of disinterest and distrust of what would later come to be called scientific research, we notice a certain tone of revenge in the ways in which researchers described their objectives when searching for ways to record the images of the camera obscura. The metaphors they used, like any good metaphor, don’t function as literal truths, but neither are they entirely devoid of meaning. They were clearly celebrating a victory: “Wedgwood went to work with the purpose of making the sunbeam his slave, enlisting the sun in the service of art and compelling the sun to illustrate art and portray nature more faithfully than art had ever imitated anything illuminated by the sun.” This is how John Werge talks about Thomas Wedgwood’s research. It’s also important to remember that “light” carries a heavy heritage as a symbol of divine presence and manifestation: “Let there be light – and there was light” (Genesis 1:3).

In 1862, Arthur Chevalier wrote about his father’s achievements and recounted some of his relationship with Daguerre in the book Charles Chevalier. He describes Daguerre’s frustration in the following terms: “After having obtained the image, he could not preserve it, while contemplating his captive, it faded, returning to the source from which it had emanated”, created by light and destroyed by light, the image was described as a “captive”, as the target of a capture.

The science brought about by Modernity was all based on the idea of domination over nature, of explaining all its secrets and making it work for human wealth and glory. The conception of nature for Enlightenment philosophers was that the Universe was like a great machine that moved on its own and was governed exclusively by its own laws. A marvelous machine, but not to be contemplated or worshipped, but rather to be deciphered and explored.

In his important and enlightening speech to the Academy of Sciences in Paris, François Arago included photography among the scientific discoveries designed to inspect the secrets of nature. He ranked Daguerre’s discovery alongside the telescope and the microscope. Regarding the latter, he made a very iconoclastic and premonitory statement: “The microscope subsequently revealed in the air, in water, in all fluids, these animals, infusoria and strange reproductions, in which it is hoped one day to find the first germs of a rational explanation of the phenomena of life.” He was an atheist and also had many works specifically on light. He supported the wave theory, as it was the most materialistic approach, and made an important contribution to understanding the polarization of light and determining its speed. Getting light to print its own images must have seemed to him one of the great achievements of the century.

The idea of discovering the laws of nature went beyond the physical world. The program was to use this knowledge to understand our own relationships as human beings. Politically, this was the cornerstone of the edifice of Modernity. In nature, there would be the logic and foundations to regulate even social life and this was the key to getting rid of spiritual and political tutelage, both of which were supported by traditional thinking, based on the authorities of the church and the nobility, rather than the scientific analysis of facts and observations. Photography was presented as freeing images from the intermediation of an artist. Objects drew themselves in the same way that people would direct and decide on their lives in a democratic republic. On the basis of the preliminary agreement between Niépce and Daguerre, photography is defined in the following terms: “M. Niepce, in his effort to fix the images that nature offers, without the help of an artist, carried out investigations, the results of which are presented by numerous proofs that will substantiate the invention. This invention consists of the automatic reproduction of the image received by the camera obscura”(Fouque p.162). The automatism, the surface that presented an image without having been touched by anyone at any stage of the process, that was the wonder of photography. As for the image itself, everyone was very willing to overlook its defects and limitations.

Richad Buckley Litchfield was Thomas Wedgwood’s biographer. In the following passage, he does not hide his disappointment at the lack of perspicacity of Humphrey Davy, a competent chemist and Wedgwood’s collaborator in his experiments with paper impregnated with silver salts, for not realizing the importance that photography could have. He uses exactly this characteristic of the new process to highlight its most important quality: “Up to this point, every image produced by man had been made by the human hand, guided by the human eye. – But here was a photograph, or a kind of image, a representation of an object, which arose by the spontaneous action of natural forces, by a chemical change produced by the action of light.” What Wedgwood and Davy didn’t realize was how this characteristic of photography was in tune with the liberal thinking that Western culture was taking on. As scientists, they must have evaluated the image objectively, the image in itself, and given up, as it certainly wasn’t the best.

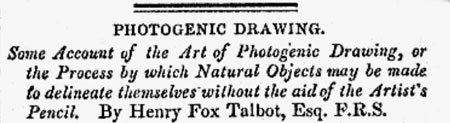

Henry Fox Talbot was an Englishman who, at the same time as Daguerre, developed a substantially different process using paper and the negative/positive concept. He partially presented his discovery to the Royal Society in London on January 31, 1839. He didn’t disclose all the details because he wanted to obtain a patent and have control over the invention, which he did. Once again, the way he presented his invention, the way he describes it in the title of his exhibition, underlines the real strength and attractiveness of the new photographic process. It was published in the Literary Gazette (London) No. 1153 (February 23, 1839). Below is the headline (taken from the excellent online source Midley History of early Photography – Derek Wood)

“… objects set to delineate themselves without the aid of an Artist’s Pencil”, this is the most important quality of photography, more than its actual ability to faithfully translate a visual impression. Later, after some important improvements to his Calotype, Talbot published a collection of images that he called “The Pencil of Nature”. This is also what Robert Hunt underlined in his 1844 book, Researches on light in its chemical relations, in which he says: “Europe and the New World marveled at the fact that light could be put to delineate from solid bodies, beautiful delicate images, geometrically true, of the objects it illuminates”.

This change in the concept of nature in relation to images also had an impact on painting. As early as the Renaissance, landscapes, which were just a backdrop for biblical, mythological or battle scenes, began to receive special attention. In the 19th century, at the same time as Niépce was experimenting with all kinds of materials “trying to fix the images that nature offers”, painters later known as the École de Barbizon, among them Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, Charles-François Daubigny, Jean-François Millet and Théodore Rousseau were trying to fix the images that nature offered in their own way. Before that, landscape paintings were made on the basis of previous landscape paintings and always in the studio, never live. But this began to be questioned, for example by the English painter John Constable (1776-1837), who questioned why the foreground of the landscape should always be in brownish colors, why not look at the real colors that nature offers and paint them as they are?

At the same time as photographers were setting up their tripods and cameras for a “Photographic Drawing”, painters were setting up their easels and canvases to paint d’après nature. The positioning was the same, only the instruments were differente. Photographers wanted to get rid of the artist’s interpretation, artists wanted to get rid of old academic formulas. Everyone wanted to get rid of any authoritarian restrictions. Nature emerged as the universal reference, neutral, available, perennial and omnipresent. Nature was the bet to replace the traditional sources of guidance and knowledge. This was the project of the Enlightenment and photography could not have been born without it.

This text originally appeared as part of my review of the Nicéphore Niépce Museum, published on July 4, 2017. But for its autonomy of reading and questionable relation to a museum review, I have separated the initial text into two independent texts. Find the museum visit review in the following link:

Nicephore Niépce Museum review