Gruppen Antiplanet | Steinheil

Hugo Adolph Steinheil launched his Aplanats in 1866. It was a revolution in photographic optics. The basic idea behind these designs was symmetry, two identical doublets with the diaphragm in the center.

The Antiplanet, on the other hand, was a different story: it was an alternative to the Aplanat and a daring optical design. The symmetry of the Aplanats eliminated distortions, but the image quality for distant objects suffered from aberrations and lost definition. Adolph Steinheil then decided to break the symmetry and set out to develop a design with four elements and two different groups. In 1879 he launched the Gruppen Aplanat with f/6.2 and a 56º angle of view, still using the concept of doublets with flint glass in both elements.

In 1881, unsatisfied, he returned to the crown/flint doublets which, on their own, had a horrible spherical aberration, but one compensated for the other. The name Antiplanet was chosen to signify something in opposition to the Aplanats because of their break in symmetry.

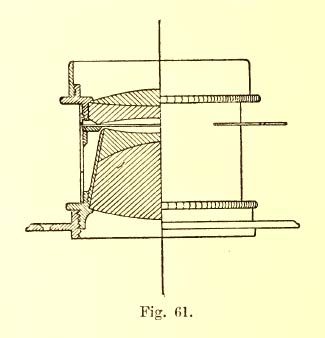

In Charles Fabre’s 1889 encyclopedic treatise, the Gruppen Antiplanet is shown with its conical rear elements (image above).

Adolph Steinheil had also been researching the advantages of increasing the thickness of the glass and minimizing the air between the elements to reduce flare. In the Gruppen Antiplanet we have a minimal gap through which a diaphragm is inserted and the rear group windows form a very thick block indeed.

Aesthetically, an optical glass block like this is very beautiful and impressive to look at and handle. The space between the groups is so narrow that when inserting the Waterhouse-type diaphragm it’s not difficult to end up scraping off a bit of the black varnish that is applied to the edge of the lenses, as can be seen in the photo above.

What was at stake in the development of the Aplanats and then the Antiplanets would be the first truly general-purpose lens for photography. Until that time, the photographer had only had portrait lenses like the Petzval, landscape lenses that were simple achromatic doublets with the diaphragm at the front and some wide-angle lenses like Harrison’s Globe (1860) and Emil Busch’s Pantoskop (1865), which were close to 90º but with f/30 or f/25 apertures. There was no lens that was reasonable on all three counts at the same time: angle of view, brightness and sharpness across the entire image field. Without such a lens, photography couldn’t have amateur cameras with fixed lenses, not with the level of sensitivity of the wet collodion that was the method in vogue at the time. Gruppen, which means “groups” in German, would be this medium lens, between portrait and landscape, and could work in many situations. It would be the long-awaited general-purpose lens.

Photography has always depended on the simultaneous development of glass, geometric optics and the chemistry of sensitive materials. Each time one of these three pillars moved from one step to another in its development, it eased the demands on the other two. This is how even the meniscus, the simple concave/convex lens, went a long way in the 20th century in popular cameras, thanks to the introduction of silver gelatine for which apertures such as f/16 or f/32 were no longer barriers to photography in many situations.

Hugo Adolph Steinheil’s Gruppen Antiplanet, designed with the mathematical tools of Philipp Ludwig von Seidel, was one of the high points reached before new glasses were developed that would finally allow the production of anastigmatic lenses whose mathematics was already known.

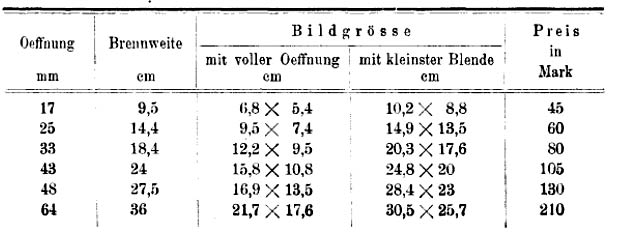

The table above shows the 6 sizes in which it was manufactured. This Gruppen Antiplanet is the third line and has a focal length of 18.4 cm. The entrance pupil (Oeffnung) is 33 mm in diameter. Its aperture is therefore f/5.6, very bright for a general-purpose lens. The angle of view is 70º(Eder) with the diaphragm closed at f/16. The format is 12.2 x 9.5 cm with the diaphragm open and 14.9 x 13.5 cm with the diaphragm closed, as shown in the table above. These measurements are generally very strict and refer more to the area of sharpness. I’ve been shooting with it in the 13 x 18 cm format and haven’t noticed any fall-off.

The serial number of this lens is 14.534, according to Agostini this indicates a year of manufacture in 1885. On the body is written “Steinheil in Munchen nº 14.534 patent”. Unfortunately, Steinheil had a bad habit of engraving the name of the lens on the flange and, even more unfortunately, many lenses were separated from their cameras without the flanges being removed so that they would remain together. So today it’s very common to find Steinheil lenses without a clear name to identify them because they’re missing the flange. In the case of this Gruppen Antiplanet, this is less serious because its design is so distinct from everything else that it’s easy to be sure of its identity. But with many Aplanats the issue can get quite complicated as many different types look alike.

As well as having no flange, this lens also lacked the Waterhouse diaphragms. The ones shown in the photo were calculated using this method and then printed in black ABS on a 3D printer. Without any diaphragms it has an entrance pupil of 33 mm which gives it an aperture of f/5.6. The smallest aperture I made, which you can see in the photo, corresponds to f/32.

As if to compensate for the fact that it came without a flange and diaphragms, the general condition of the body, varnish and glass is excellent and it is a great pleasure to photograph with this landmark in the history of photographic optics. The two photos below were taken in 13×18 cm format with Fomapan100 developed in Parodinal and contact copied onto Foma 111 paper.