Albumen printing paper

The printing process using albumen as a base, egg white, reached an operational version with the Frenchman Louis Desire Blanquart-Evrard in 1850. This was when he was trying to perfect Talbot’s salted paper and, as we shall see, the two processes actually have a lot in common.

It’s difficult to talk about pioneering photography, because at that time everything was tried and published, even if the result wasn’t exactly a success. But it is accepted that it was with Blanquart-Evrard that the method reached a stage that really deserves to be called “the invention”.

The importance of albumen paper is enormous. Especially when seen in combination with Scott Archer’s wet plate, collodion, which came into the world the following year to produce negatives. The combination is very fortunate because while the glass negative gives a richness of detail incomparable to the negative known until then, Talbot’s paper calotype, the albumen paper presents a surface that has a discreet sheen which, thanks to its very wide tonal range, renders all the details of the negative wonderfully well, both in the shadows and in the high lights.

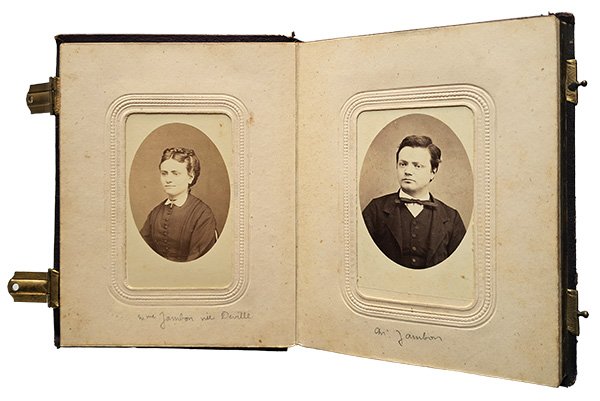

Virtually all photographs printed between the 1850s and the end of the 1880s were made using the glass negative of the wet plate and contact printing with albumen paper. There were other processes, but this combination completely dominated the scene. Suffice it to say that it was the medium and even the enabler of the carte de visite, which is often referred to as the fever or rage for collecting and having portraits taken, throughout this period.

The albumen paper process

Basically, if in salted paper the sheet is bathed in an aqueous solution of sodium chloride, in albuminated paper it is bathed in a solution of sodium chloride enriched with albumen.

1- Preparing the albumen

The egg white is separated, beaten into snow and mixed with a saturated solution of table salt, sodium chloride. This mixture is left to stand overnight and the yellow liquid that forms at the bottom of the container is separated.

2- Covering the paper with albumen

The albumen is placed on a tray large enough for the paper to be prepared to float in it for a minute. The paper is removed and hung up to dry completely.

3- Sensitizing

A strong solution of silver nitrate is prepared and the paper is floated, obviously on the same side where albumin has been applied. From then on, some of the silver in the silver nitrate changes salt and joins with the chloride to form silver chloride, which darkens when exposed to light. You can use very dim light or an amber or red safety light, as this paper is only sensitive to ultraviolet and blue, which is the most energetic part of the spectrum. For drying, it is safest to leave it in total darkness.

4- Exposure

Exposure doesn’t have to be immediate, but it’s best if it doesn’t take weeks or months either. You should press the paper to be printed against the negative and both against glass. Exposure is most effective in direct sunlight or even in the shade, but in the light of a blue sky. It is possible to inspect the image forming as the darkening begins immediately. To do this, simply open the joint on the contact press, preferably protecting the paper from the strongest light so that it doesn’t tarnish.

5- Finishing

The paper then needs to be washed to remove the silver nitrate that hasn’t reacted with the sodium chloride. Then a sodium thiosulphate bath will remove the silver chlorides that haven’t darkened, so that they don’t darken later. Finally, the paper is washed thoroughly with a few changes of water in the tray, interspersed with agitation. Then just dry the paper.

6- Toning

This step is optional, but it greatly increases the permanence of the image. It is usually done with a solution of gold chloride. Without toning, there is a tendency for the shadows to fade and, after a few years, a general lightening is noticeable.

Conclusion

When photos printed on albumen appeared, everything that had gone before seemed more like a prelude. Everything that came after was compared to albumen in the first place. It defined what a photograph was, physically speaking. It would be on paper but not inside the paper, as seemed to be the case with salted paper, of which you could see the fibers and the image was more of an intruder. In albumen, the image seems to define a new or even dispense with a real surface. It is virtual, invisible, illusory, in which the image reigns absolute. It brought transparency to the photographic medium, as if there were nothing between the viewer and the subject. It was as if Leon Battista Alberti’s verdict on the essence of images had finally come true.

If you are in the Photographic Processes theme circuit:

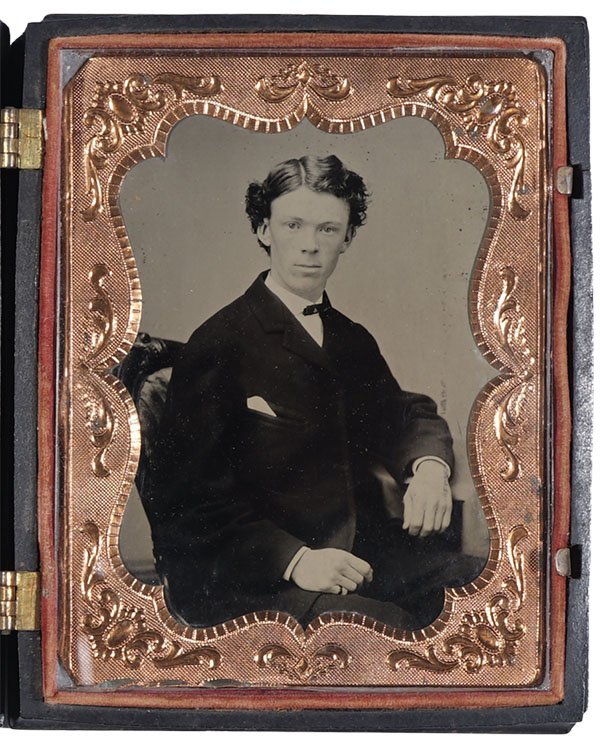

Although it had a short life, the daguerreotype created a standard for what photography would be as a luxury item. In the next room, you will meet its heir: the ambrotype. A direct positive process on glass that used wet plate collodion but created a unique piece that was usually stored in richly decorated cases.