Dry Plates | Richard Maddox

If in 1850/51 the pair of collodion negative and albumen paper positive unleashed an avalanche of professional photographers making millions of cartes de visite for a public enraptured by its own image, it was in 1871 that the new photographic avalanche that would arrive at the turn of the 20th century began to take shape, but this time it was an avalanche of amateur photographers.

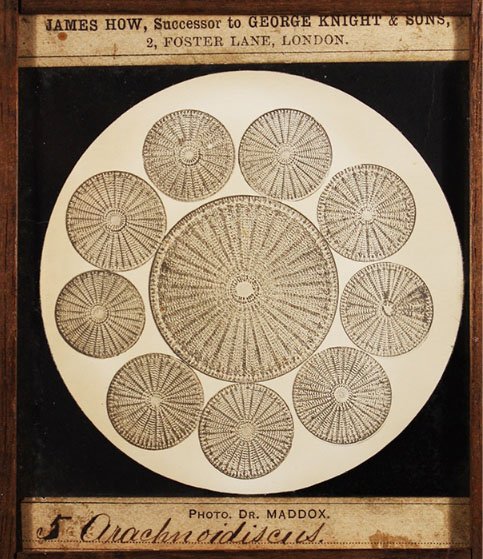

Richard Leach Maddox was an English doctor who specialized in photomicrophotography. His images of algae, insects and bacteria were recognized worldwide by the scientific community. The technique involved the use of microscopes and wet plates. The problem was that the vapors from the ether and alcohol used to prepare the collodion began to deteriorate his health, so he decided to investigate less aggressive substitutes for use as a suspension medium for the silver halides.

source: microscopist.net

–

By 1871 his health was as bad as he was close to find what he was looking for. But feeling that he would have to reduce his workload, he decided to publish what he had already found and leave it to others to perfect his method. He didn’t sell the idea, he didn’t patent his discovery, he simply published an article in the British Journal of Photography explaining the stage of his research.

In his book Photography Essays & Images, Beaumont Newhall published the entirety of Maddox’s article. I reproduce its last paragraph here: “As there is no chance of my being able to continue these experiments, they are here placed in their crude state for the readers of this journal and may receive corrections and improvements from more skillful hands. As far as can be judged, the process seems to merit more carefully conducted experiments and, if it proves worthwhile, adding another hand to the photographers’ wheel.”

From artisanal to industrial

All previous processes, since the daguerreotype itself, used the support of metallic silver, or paper or a thin layer of collodion on glass, and this support was bathed in a solution of silver nitrate, insensitive to light, and some other solution containing some compound with bromine, chlorine or iodine, so that these would steal some silver atoms from the nitrate and form the expected and desired light-sensitive crystals on the surface.

This physical configuration did not allow them to control what was happening chemically. The compounds were known in terms of their reactions and atomic masses, so they knew how many grams of silver nitrate would be needed to react with how many grams of potassium bromide, for example, to form how many grams of silver bromide, the light-sensitive halide. But the bath method didn’t allow this control.

In the case of gelatine, the approach is completely different. The sensitive crystals are not precipitated on the surface of the support, metal, glass or paper, but in a laboratory and later industrial container. It’s a closed system. The emulsion is prepared, calibrated so that something very close to 100% of the silver contained in the form of silver nitrate is converted into silver halides that are potentially sensitive to light. Without going into too much of the chemistry of the process, it’s enough to know that it’s precisely the final concentration of silver ions in the emulsion that will determine its sensitivity, its speed.

It was this control and predictability that allowed photography to move from a handmade system to an industrial one. This finished emulsion is then applied to any inert support such as glass, paper and later film. The whole process is measurable and, if repeated in the same way, will give the same results.

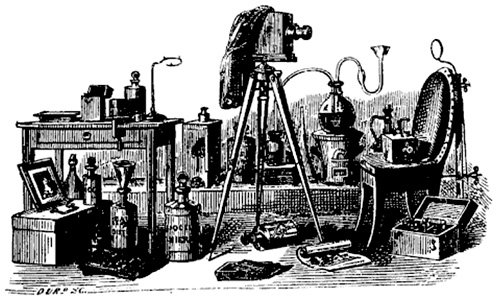

It was this new approach that enabled the industrialization of photographic plates. Since its invention, photography had been an activity in which the camera was just one of the instruments in a paraphernalia that involved many other laboratory devices and chemical processes for preparing and developing/printing the photos. The degree of involvement of the photographer was very high and demanded a wide range of skills and knowledge. For the first 50 years, the practice of photography was restricted to professionals and amateurs who, as well as being very dedicated, also needed a lot of space, time and money.

The gelatin dry plate process

In general terms, the production of dry plates as described by Maddox in his 1871 article comprised the following steps. The units were converted to the metric system and rounded:

1- Preparing the gelatine

Wash the 2g of gelatine in cold water and let it absorb the water for several hours, then drain off the excess.

2- Gelatine is heated so that it melts

Pass the gelatine into a wide-mouthed container in a heated bain marie so that the gelatine dissolves, add 14ml of water and two drops of acqua regia (a mixture of concentrated nitric acid and concentrated hydrochloric acid). The acid had the role of partially breaking down the gelatine so that it could then spread more easily. But this procedure was abandoned in later formulas.

3- Addition of bromine

Half a gram of cadmium bromide dissolved in 1.7 ml of water is added to the gelatine and gently stirred. This compound is highly harmful to health, and as its role is only to donate bromine, it was later replaced by potassium bromide, which under normal working conditions does not pose any danger.

4- Silver nitrate solution

One gram of silver nitrate is dissolved in 1.7ml of water in a test tube.

5- Precipitation

The two containers are taken to a dark place and the silver nitrate solution is slowly added to the gelatine while the mixture is stirred all the time.

6- Covering the boards

The emulsion produced has a milky appearance and is left to rest for a while. Next, clean glass plates are placed on a heated metal plate, the liquid is poured over them, spread with a glass rod to cover their entire length and the plates are left to gel and dry.

Results

Maddox exposed the plates by contact with various negatives and reports in his article that, immediately after exposure, they showed no image at all, but that when bathed in pyrogallic acid, a developing agent, they showed an image “very delicate in detail with a color varying from beige to olive, after washing and drying they presented a shiny surface”.

What he had at this point was not something operational, not for contact and even less for the camera. But this article has encouraged other researchers to try this route of preparing the gelatine emulsion in a controlled system, independent of the support to which it will be applied.

What Maddox needed was basically to get rid of the by-product of the fallout. It’s not difficult to understand. Here’s a very simplified version that serves as an introduction to the basic concepts:

1- It started with two reagents added to gelatine, neither of which is sensitive to light:

Cadmium bromide + silver nitrate.

2- The first ones combined to form two others:

Silver Bromide + Cadmium Nitrate

You can see that there has been an exchange. The Nitrate was with the Silver and at the end it is with the Cadmium. The Silver was with the Nitrate and at the end it is with the Bromine. Now, Silver Bromide, which is sensitive to light and if exposed and revealed will form metallic silver, will darken the gelatine.

The name of this stage of the preparation is precipitation. But isn’t precipitation falling? To drop from top to bottom? Precisely, this name comes from the fact that silver bromide is very sparingly soluble and forms crystals which, because they are denser than water, precipitate to the bottom of the container. That’s where the gelatine comes in: it’s inert, it doesn’t react, but it forms a medium thick enough to keep the silver bromide crystals in suspension. A medium is formed in which these small crystals, in the order of 0.1 microns in Maddox’s formula, float in a homogeneous mass. It is then ready to be applied to a support such as glass, paper and film.

If it weren’t for the gelatine, all the crystals would form a thin layer at the bottom of the container and it wouldn’t be possible to distribute them evenly over a surface. Note that in salted paper or calotype, made with Silver Chloride and Silver Iodide, which are also crystals, this problem doesn’t exist because the paper itself takes care, with its fibers, of holding these crystals spread evenly over its surface. In its own way, collodion also fulfills this role.

So far Maddox was 100% on the right track. The problem is that Cadmium Nitrate, which also formed in the exchange, causes two serious problems if left in the gelatine. Firstly, it is hygroscopic and absorbing water compromises the stability of the emulsion, which will never dry completely. Secondly, it restricts the action of the developer, thus reducing the sensitivity of the emulsion, which cannot be fully developed. We therefore needed to find a way of eliminating it.

But it wasn’t quite clear how to get rid of the by-product of precipitation. The decisive step was the procedure suggested by Richard Kennett in 1874. As silver halides are practically insoluble, but nitrates are soluble, there was a way of washing the gelatine so that the water would wash away the unwanted, soluble part. Gelatine has the characteristic of swelling and allowing water to penetrate its structures, but this has a superficial limit. Kennett’s method was to chop, shred, slice or otherwise transform the block of gelatine into small pieces and wash it with cold water until all the nitrate from x, y or z was removed. This is still the method used today.

Another decisive contribution came from Charles Bennett in 1878. He discovered that by heating the emulsion and keeping it warm for a certain time, the smaller crystals (which are more soluble) dissolve, and their mass is redeposited on the larger crystals, making them grow. This considerably increases the sensitivity of the emulsion.

With these two contributions, washing and maturing, emulsion with silver gelatine became absolutely viable and in many ways far superior to collodion, which was the dominant process at the time.

Further developments

As they say, from this point on, the rest is history. The advantages of silver gelatine dry plates were immediately realized and many companies began to produce and offer them ready to use in a wide variety of formats. In an industrial process, or even a more sophisticated artisanal process, various additives and details are used to improve the performance and characteristics of the emulsion, but it was this beginning with Maddox, Kennett and Bennett that opened the door to yet another revolution in photography.

You can imagine, with all the previous processes, how photography must have seemed complicated, laborious and with a huge barrier to entry, because the first steps were fatally frustrating until you got the hang of it. With silver gelatine emulsions, this high wall disintegrated as if by magic. From the 1880s onwards, all you needed was a camera, some tanks or trays and a few processing liquids, which were also sold ready-made, and anyone could become a photographer. It was the first great wave of amateur photography.

Alexander Black, as well as being a very popular writer in the United States at the end of the 19th century, was also a photography enthusiast. In an article published in 1887 entitled The Amateur Photographer, he gave a good measure of what was happening:

There were, in fact, amateurs making wet plates, and today there are some who follow the example of many professionals by sticking to the old method. But amateur photography today practically means dry-plate photography. It was the amateur who welcomed the dry plate, at a time when the professional showed only cautious tolerance. Why the amateur welcomed it is beyond explanation.

This short, blunt paragraph also needs no further explanation. But it is interesting that it also announces a split that was about to happen in photography. The “cautious tolerance” with which professionals received the dry plates already anticipates the conflict of interests that the new technology, which, to use a conteporary word, we can call inclusive, would promote in photography. The difficulty of photographic processes was also a protection of the professional labor market. The reaction to the dry plate bears some resemblance to the reception that many professionals gave to the cell phone.

Alexander Black’s full article is in the book Photography Essays & Images by Beaumont Newhall.

What happened to Maddox?

This is one of the many ironies in the history of photography. Maddox, who could no longer work because of his health, was forgotten and driven into a condition of very severe financial hardship. Meanwhile, as early as the 1880s, between 20 and 30 companies started producing and selling dry plates in the UK alone, and in the United States, at least a dozen large companies were born. Several local brands also sprang up in France and Germany. Fortunes were being made thanks to something he had started, while he himself was living on the edge of poverty.

Fortunately, a famous photographer called Andrew Pringle, in 1890, sympathetic to such a sad end for someone who had helped so much in photography, launched a rescue campaign, the Maddox Testemonial Fund. He managed to provide a modest pension and a decent standard of living for Maddox’s final years. He died in 1902.

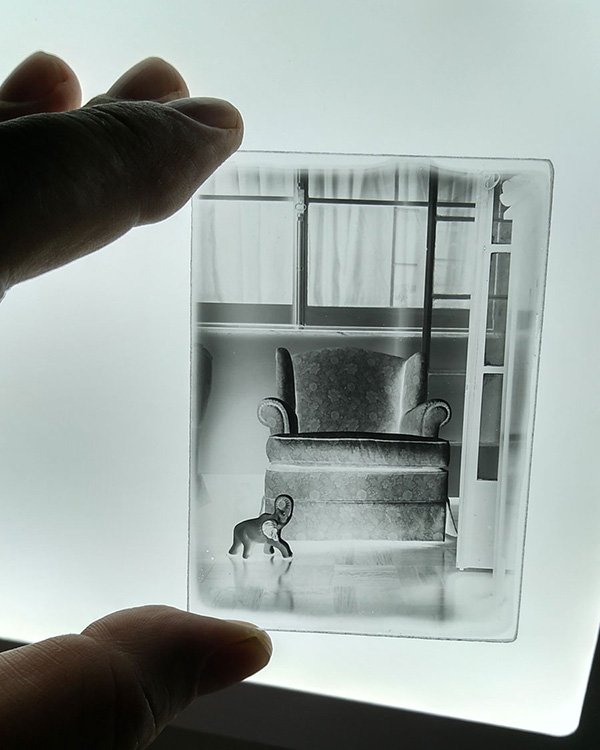

Curiosity: Among the many possible handmade photographic processes that can be done today, the dry plate is a very interesting and perhaps not very widespread option. This plate above I made with a small 6.5 x 9 cm camera called Patent-Etui.

If you are on the Photographic Processes theme circuit:

We have reached the end of this circuit, focusing on the use of silver in the production of the photographic image. Gelatin emulsions, which began with dry plates, is like the pinnacle of analog photography. It would soon migrate to flexible films and also papers and it would become synonymous with “photography” throughout the 20th century.