Hasselblad | Victor Hasselblad

The history of the Hasselblad camera begins with a model for military use developed for the Swedish air force in 1940, right at the start of the Second World War. Due to supply interruptions or difficulties, or even nationalistic concerns, German technology, the best at the time, was not considered an option. Instead, a talented young man of 34, Victor Hasselblad, was asked to develop a medium format camera, portable and suitable for aerial reconnaissance work. Legend has it that he was given a German camera to copy and replied: “No, not one like that, but a better one.”.

But as far as the optics were concerned, there was probably no scope for last-minute developments and the German ones were used instead. The standard lens was a 13.5 cm f/2.8 Zeiss Biotessar. For telephoto, the options were 24 cm f/4.5 Schneider Xenar or 25 cm f/5.5 Meyer Tele-megor.

The model developed was called the Ross HK-7. But this Ross had nothing to do with the British lens manufacturer, it was simply the name of a workshop that Victor had opened in Gothenburg. Precisely because of this coincidence, when the brand went international, he later had to change the name, removing the Ross and making it Hasselblad.

The HK-7 was large, 31 x 26 x 17.6 cm and weighed 4.8 kilograms. It took pictures in 7 x 9 cm format, hence the 7 suffix in its name. The photo above gives a better idea of its imposing size and truly military design. I just wonder what a Rolleiflex is doing on the ground. Was it the back-up?

Victor Hasselblad came from an elite Gothenburg family with a tradition in photography. Since 1885 it had been a distributor for the Eastman Dry Plate & Film Company (the future Kodak). He had a passion for photographing nature. From the start of the HK-7’s development, Victor didn’t see the military field as his ultimate goal, as he already imagined how it could be an ideal camera for “civilian” photography.

In the photo above, Victor uses a Graflex Auto RB to photograph birds (photo by: Stig Hasselblad, 1927). The monoreflex concept, when the viewfinder displays the image from the camera lens itself, is certainly the ideal configuration for photography with long lenses and moving subjects. This was the type of camera that Victor later adopted for his project.

But in the 1940s, anyone thinking of launching a new camera for a more sophisticated audience had to compare themselves with Leica and Rolleiflex and be very clear about where the project was going to differentiate itself so as not to be just another copy of those that dominated the prestige camera market. It’s also important to remember that the Exakta VP, a monoreflex using 127 film, was a camera used by Victor Hasselblad in the 1930s and undoubtedly left its impression on the young photographer. The Exakta was the true pioneer of medium format monoreflex and interchangeable lenses. It was launched in 1933 by Ihagee in Dresden. It was a very reliable and practical camera, making 4.5 x 6 cm negatives. But as a matter of brand strategy, Ihagee preferred to give priority to the Kine Exakta, using 35 mm film, and its medium format was left behind.

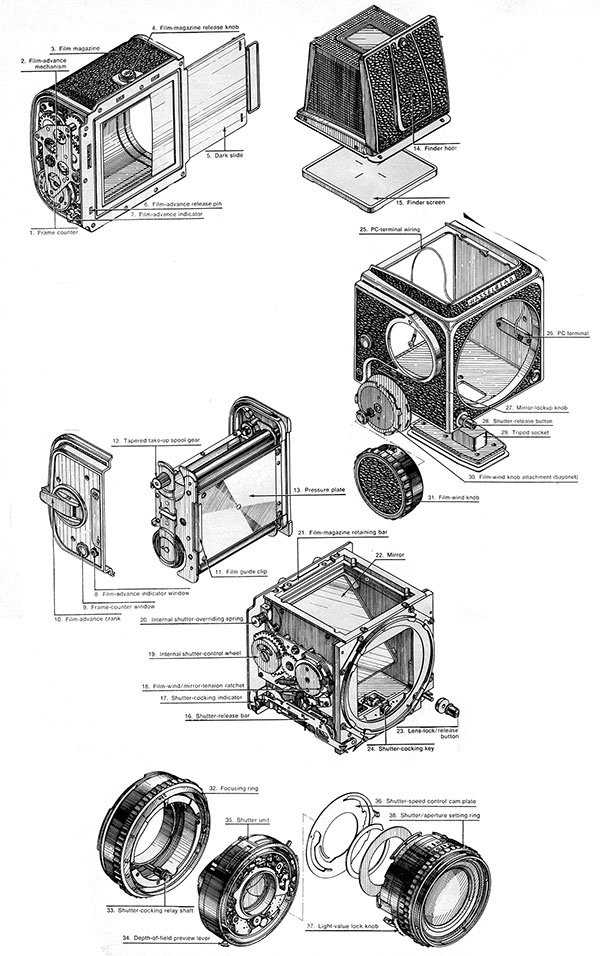

The idea with Hasselblad was to offer a unique and very happy combination. It seems to bring together everything that was best at the time and also some important new features. The Hasselblad 1600F, for the consumer market, was launched in 1948 in New York with the following features:

- 6×6 cm format – established by Rolleiflex as the best size x image quality ratio and using the renowned and available 120 film.

- Excellent, interchangeable optics – like Leica or Exakta.

- Monoreflex – Like Graflex in large format or Exakta in medium format

- Interchangeable backs – a great addition to a roll-film camera, providing the ease of changing the type of film as one would do with sheet or plate camera.

- Very compact with a cubic body with a very attractive design reminiscent of the minimalism of the military equipment from which it was born.

Shutter, the final touch

A very interesting point about Hasselblad was its move against the trends of the time by adopting leaf-shutter shutters in 1957, in which each lens has its own shutter. First of all, it’s much more rational to have a single shutter on the camera body and not multiply it by the number of optics. This began with the Leica in 35mm format, followed by the Exakta and it was in this configuration that the Japanese SLR (monoreflex) cameras gained absolute market leadership in the 1960s. German monoreflex cameras, such as the Contaflex, Bessamatic or Retina Reflex, which insisted on keeping the leaf shutter, like the Compur and its variations, couldn’t compete and were discontinued.

In medium format, however, the situation is a little different. The size of the frame already begins to balance out the advantages and disadvantages of each of the curtain shutter options on the body or leaf shutters on the lenses.

The first Hasselblads, starting with the military HK-7 and then the civilian 1600F version from 1948, came with curtain shutters. This probably seemed like a solution in line with what was available at the time for handheld cameras, such as the Ermanox, Deckrullo and Graflex Speed and SLR. However, the need to miniaturize the mechanism compromised the reliability of this system. The first Hasselblad cameras were susceptible to shutter breaks, to the point where the brand’s image began to suffer.

In 1957, Victor Hasselblad made the bold move of launching the 500 series with a body devoid of a shutter, and this was now a Synchro Compur incorporated into the lens barrels. The new Hasselblad was something of a hybrid between large, medium and small format. Like a Linhof Technika or Kardan, it left the shutter to the lens. Like a Rolleiflex, it had a mirror with focus and framing in a ground glass on the top of the camera and could be equipped with a prism for eye-level viewing. Like an Exakta, or a Nikon F that would come along the following year, it was a monoreflex.

This was in fact the configuration that definitively made Hasselblad the best medium format camera for the next 50 years. The evolution of the Hasselblad 500 series represents the pinnacle of the modular concept of leaf-shutter SLR cameras. Starting with a bold change of direction in 1957, the series went through several major revisions and improvements until it reached the final, but still fully mechanical models.

Chronology of the 500 Series Mechanics

1957: Hasselblad 500C

The basis of the modern system. It replaced the focal plane shutter with a blade shutter integrated into the lens, allowing flash synchronization at all speeds.

1970: 500C/M

The “M” stands for “Modified”. This milestone introduced user-interchangeable focus screens, allowing photographers to easily swap a standard screen for a microprism or split image version.

1988: 501C

A “back to basics” model that simplified the system by removing the shutter signal window mounted on the camera body. It was launched to offer a more affordable and purely mechanical entry point into the system.

1994: 503CX / 503CW

While the 503 series introduced TTL (Through-The-Lens) flash metering, the 503CW (1996) became a mechanical milestone for its **Gliding Mirror System (GMS)**. This solved the problem of viewfinder vignetting when using long telephoto lenses.

1997: 501-CM

The ultimate refinement of the 500 series. It combined the simplified, non-electronic body of the 501C with the advanced **Sliding Mirror System** of the 503CW. It is often considered the most elegant and reliable mechanical “box” in the history of the system.

2013: End of the series

The 503CW was the last V-system camera to be produced, marking the end of the line for the all-mechanical, film-based system that Victor Hasselblad devised in the 1940s.

In the museum’s collection

This is a 501-CM manufactured in the year 2000. This model, launched in 1997, was like a “Final Mechanical Statement”. It arrived at a time when the industry was becoming increasingly electronic, but it reinforced the promise of 1957: a reliable yet sophisticated and complex tool. Full of logic in its controls and protections, but still purely mechanical and modular.

In the photo above, it is using a Planar 80mm f/2.8, which was its normal lens and corresponds to the 6 x 6 cm diagonal of the frame.

The standard viewfinder is simply a shield against outside light to facilitate direct viewing of the image that the lens projects onto the focus screen through the mirror.

Under ideal conditions, the image is seen as in the photo above. In this case I was indoors framing an outdoor scene. But when you’re out in the open, you have to move closer to cover the lens, shade your head and reduce the light hitting the screen. If you move your eye closer, you need to activate a complementary magnifying glass, built into the viewfinder itself. I never use this system. Since you have to get closer, I prefer the prismatic viewfinder, which doesn’t invert the image horizontally and already has its own little darkness.

These are options for putting together a kit with a longer lens, Makro Planar T* Cfi 120 mm, f/4 (left) and an angular lens, in this case the Distagon 50 mm, f/4 as well. The Distagon has a floating element, i.e. an internal lens that can be moved and reduces the vignetting effect that is common with wide-angle lenses.

It’s this scale where you have to put the distance at which the focus ring is set and this has the effect of not darkening the corner of the photos. But several times I’ve forgotten to do this and what comes out is no disaster. Nothing that can’t be corrected in the lab.

Above, a 45º prismatic viewfinder. There are 0º and 90º models too, but the 45º is probably the most versatile. The camera is mounted with a Zeiss Sonnar 250mm f/5.6. This was the lens used for the famous photo of the Earth from the Moon.

The irony is that, taking advantage of the system’s modularity, the camera used by NASA, a modified Hasselblad 500 EL, was left behind on the Moon, and only the film magazines returned to Earth.

Above is the A12 magazine, which takes 12 photos with 120 film, and next to it is a strap for wearing the camera around your neck. There were other magazines (back) for making pictures in 4.5 x 6 cm and even 4 x 4 cm, which would be a popular format for projection super-slides. These formats were also declined in 120 and 220 film, which is twice as long and therefore doubles the number of frames.

Hasselblad filters use a bayonet system and this makes them rare and expensive. A cheaper solution is to use an adapter ring that fits the bayonet but offers a thread for use with ordinary filters. Above is a B60 bayonet adapter for a 67mm thread and a B50 adapter for a 55mm thread. These are the most common.

The latest lenses have a very good anti-reflective treatment and design that helps a lot to control flare. But a lens hood is always desirable, even as protection against mechanical shocks.

On the left of the camera there is a dark-slide that allows you to close the magazine to change the film even when the roll is partially exposed.

On the right-hand side of the camera is the film advance, the photo counter and the crank to finish winding the film when it is fully exposed. Also note the shutter button on the front of the camera on the right-hand side.

If you’re using 35mm, you can’t say it’s a light piece of equipment. But with a bit of organization, it’s easy to take it outdoors. Above is a shoulder bag for which I made a wooden base to separate the camera and two PVC tubes, lined with EVA to accommodate the lenses. Above the lenses there is space for the light meter and in the pockets (on the other side) I put the two filters, plus a back and shutter release cable. Very practical. Only the Sonnar 250 mm is left out. Before I leave, I have to choose between the Makro Planar or Distagon, which one will stay at home if I think I’ll need the 250 mm.

In use

Victor Hasselblad’s original intention was for a camera for the explorer, for outdoor and nature shots, as this was his favorite type of photography.

But over the course of the 1960s, a pattern was established in which Hasselblad would find another territory and reign supreme over it for a few decades. It’s no exaggeration to say that almost every successful professional photographer would have or would like to have a Hasselblad in their studio. Product photos, photos of still things, where precision, perspective correction, focus and ease of retouching were important, were taken with 4×5″ plates and cameras like Sinar, Calumet or Linhof. On the other hand, photos of people, fashion, personalities, more elaborate editorials, and everything that required quality combined with fast action, were taken with Hasselblad.

In the 1966 film Blow-Up, directed by Michelangelo Antonioni, a famous fashion photographer played by David Hemmings could not escape this rule. There he was in the studio with his Hasselblad. But what’s interesting is that when he went out to photograph for more authorial work or pure fun, his companion was a Nikon F.

Conclusion

Cameras can be divided into categories or types. One obvious criterion is the size of the image they produce. Additional attributes such as monoreflex, twin lens reflex, rangefinder or view camera also define families within formats. Hasselblad are medium format cameras. What’s striking is that while in practically every category there is a lot of dispute about which camera is the best, in the medium format category I believe there is very little controversy in pointing to the Hasselblad as the best medium format ever made. Photographers may beat themselves up over Leicas or Contaxes, but the Hasselblad enjoys the tacit respect of everyone who has ever had the chance to shoot with it.

The Hasselblad 500 series represents an era and in a sense challenges the idea of progress. I say this because it is not possible today, nor will it be possible in the future, to build a camera with this level of sophistication and completely mechanical. Its cost would be prohibitive, unfeasible. If we simply stick to the question of image making, it’s reasonable to think that electronic/digital equipment offers something comparable and even better if the comparison is made by laboratory criteria. But for my generation, which grew up imagining that technological progress would always be accumulative, that everything gained through knowledge would always be at our disposal and would give us the power to do whatever we wanted, there is a very clear limitation: we will never be able to make a Hasselblad again.

See also:

1) Hasselblad’s website telling its story: https://www.hasselblad.com/about/history/

2) In 2023 at the Annual Meeting of the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences , A Tribute to the Memory of Victor & Erna Hasselblad was presented and the pdf is available online at this link.

Below are some photos taken with this museum kit.