Perigraphe Serie VIa | Berthiot

Perigraphe nº3 Serie VIª f/14 120 mm

Berthiot’s Perigraphe is a good illustration of something that has always been very common in photographic optics, but which can cause a certain amount of confusion. It’s the case of names that become famous, gain a reputation, and at a certain point the manufacturer makes a significant change to the design but keeps the same name on the lens to take advantage of the fame that the name already has.

The Perigraphe was launched in 1888 and was another lens in the Rapid Rectilinear or Aplanat family, which ushered in a new era in photography from 1866. As it was a symmetrical and very well calculated wide-angle lens, it lent itself wonderfully to architectural work where symmetry prevents distortion. The straight lines that are common in buildings, monuments and interiors remain straight when using a symmetrical lens.

Being a rapid-rectilinear, it had only 4 elements in two groups and therefore few air-to-glass or glass-to-air passages. This helps to reduce flare (when the lens scatters light uncontrollably). This is another very desirable feature in an outdoor lens that combines very bright skies and walls in shadow.

This was during a second phase when the company was named Lacour-Berthiot. It was founded in 1857 by Claude-Stanislas Berthiot. But in 1894, he joined forces with Eugène Lacour, and they created Lacour-Berthiot.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Perigraphe was recalculated and changed to a 3 + 3 construction, two identical groups, symmetrical around the diaphragm but with 3 elements each. This was because they wanted to take advantage of the new glass that allowed the construction of anastigmatic lenses. The Perigraphe remained a wide-angle lens, but with much better performance than its predecessor of the same name.

In 1913, Lacour retired and the lenses of that period were now only manufactured by Berthiot Paris. A forth phase came in 1934 when it became SOM Berthiot. SOM was a large fine mechanics company, founded in 1913, specializing in military equipment. SOM stands for Société d’Optique et de Mécanique de Haute Précision.

This fusion is significant of a transition between family-run optical boutiques, founded by opticians who signed their own names to their lenses, and large-scale industrial production using abstract brands.

This example represents the last phase of Berthiot, prior to the merger with SOM and still within the tradition of 19th-century optics. Based on the serial number, it was manufactured around 1920. However, it remained unchanged in the SOM Berthiot catalog until the 1950s, when it even received an anti-reflective coating. It is still a brass lens, which was the very identity of optics in the early days of photography. After the merger, as was the trend at the time, they adopted aluminum alloys and black paint to reduce weight and cost.

The VIa Series

The Perigraphe anastigmatic was marketed in two series VI a and b, the first at f/14 and the second at f/6.8. In both cases, the diaphragm is a rotating disc. The image circle corresponds to an angle of 112º. No. 3, which has a focal length of just 120mm, covers a frame measuring 18 x 24 cm. On the page of the SOM Berthiot catalog, reproduced above, we read that it is suitable for photographing “very tall monuments in cases where it is not possible to be very far”. An equivalent wide-angle lens for a 35mm film camera with a 24 x 36 mm full frame would have a focal length of 15 mm.

With these characteristics, when you consider the size of this No. 3, it really is a great lens to own and use. The barrel has a total length of 20 mm. The outer diameter of the flange is 72 mm. It’s very small indeed.

I usually only use it for 4 x 5″ or 9 x 12 cm. It’s already an angle even in that format. It’s roughly equivalent to a 35mm if it were on a 35mm full frame camera. The freedom of movement is simply enormous.

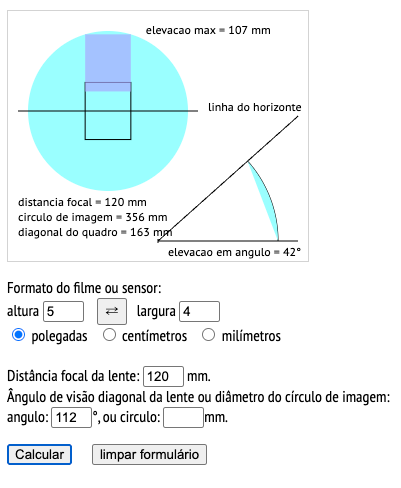

In the Fundamentals room here at the museum, there’s a calculator under the Tools tab that tells you how much you can raise the lens plate depending on the focal length and its image circle or angle of view. In the print screen above, we see the 120 mm of this Perigraphe and the 112º of the SOM Berthiot catalog calculated for the 4 x 5″ format. You can raise the lens 107 mm! It goes up so much that the horizon line is well below and out of the frame, as we see in the drawing.

In the 4 x 5″ photo above, using the Thornton Pickard Tribune, I was standing on a small track well below the level of the chapel, something between 3 and 4 meters, and it was still possible to do a front raise and keep the vertical lines vertical.

Since you can’t want everything, especially in optics, I have to say that at f/14 the image is dark and it takes a while under the black cloth for your eyes to become more sensitive. It helps a lot to put a fresnel on the ground glass. When you don’t move the lens and keep it in the center of the frame, an improvised sports viewfinder can help the composition.

Perigraphe has been a name in photography for over 60 years and has always been highly regarded for its qualities. With the more sensitive emulsions we have today at ISO 400, which in large format we can easily push to 800 or more, even its f/14 isn’t a big problem. Despite its old age and museum-like appearance, it’s a great choice for super wide-angle photography.