Spot retouching on black and white prints

Often an analog photographic print has white or black dots that need to be removed.

White dots: these are usually dust stuck to the negative or scratches that block the light from the enlarger and produce flaws in the copy.

Black dots: these are usually flaws in the emulsion, often due to processing problems such as impurities in the baths. Faults in the film itself, with modern emulsions, are quite rare, but those who make dry plates, for example, live with the need to eliminate small black dots on the print of their photos.

But retouching isn’t just corrective. There is also creative retouching to highlight elements of the photograph. In another article, I showed a local reduction that aimed to lighten the reflections on the cobblestone floor of a street in a night scene. In this article we’ll look at a case of retouching that involves both the removal of silver, thus lightening the photograph, and the deposit of pigments to darken tiny parts of the same photo. This is the type of retouching known as spot retouching.

The sparkle in your eyes

The case we’re about to see was almost obligatory in the production of studio portraits back in the day. In the photo above, it’s almost certain that the reflections in the baby’s eyes, which are so well formed and bright, were added via spot retouching. Although I’m the one in the picture above, I can’t say for sure whether it was retouching or not. It could be that the studio was equipped with some specific lighting to give these beautiful catchlights. But as my interest in photography only began later, I didn’t notice this detail.

In the absence of an appropriate and well-placed light to give that sparkle to the eye, the photographer could and can still make use of potassium ferricyanide for a very efficient chemical retouching, but to a certain extent risky because it can ruin a copy once it’s finished.

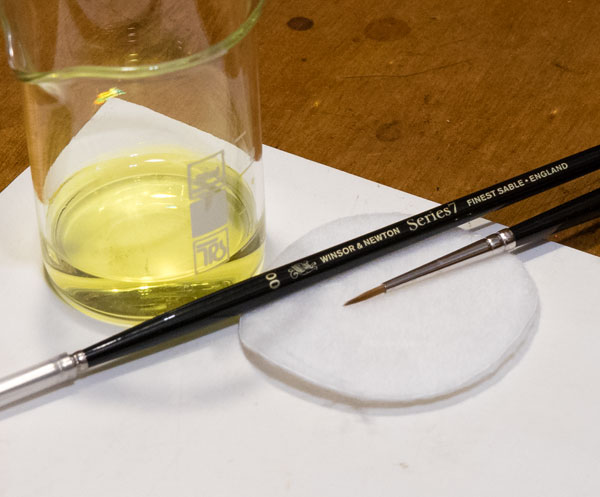

Spot retouching by reduction

There are variations, but the procedure I adopted is probably the simplest and basically consists of preparing a strong solution, in the smallest possible quantity, of potassium ferricyanide, and applying it with a zero or 2-zero or even 3-zero brush directly onto the slightly damp photo. If the copy is very small, you can even apply it with a toothpick. In the case of the toothpick, it’s a good idea to train yourself to find a way of regulating the amount of developer that will be deposited and that is the right size.

In a few seconds we see the reagent attack the silver and a little brownish or yellowish stain appears on the spot. The copy is then immediately washed with a gentle stream of water over the retouching for a few seconds and then placed in the fixative for a few minutes, like a normal fixation followed by a normal wash.

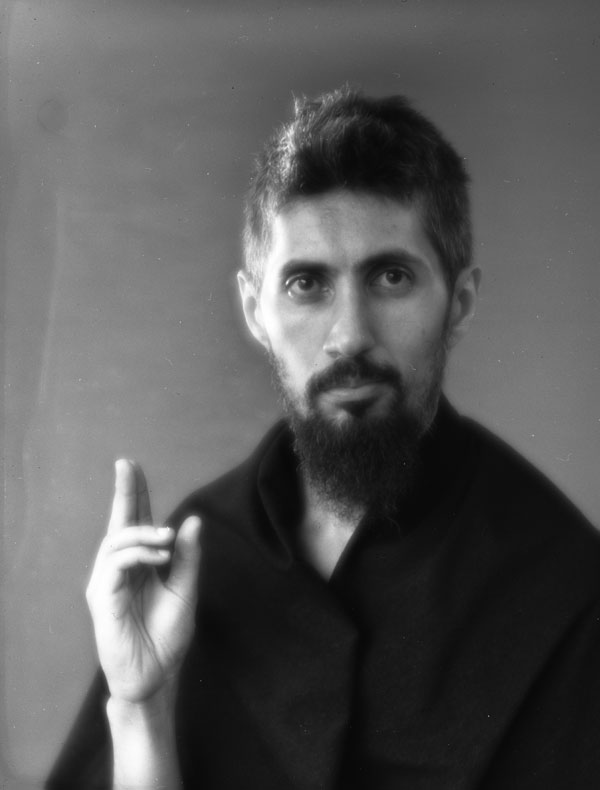

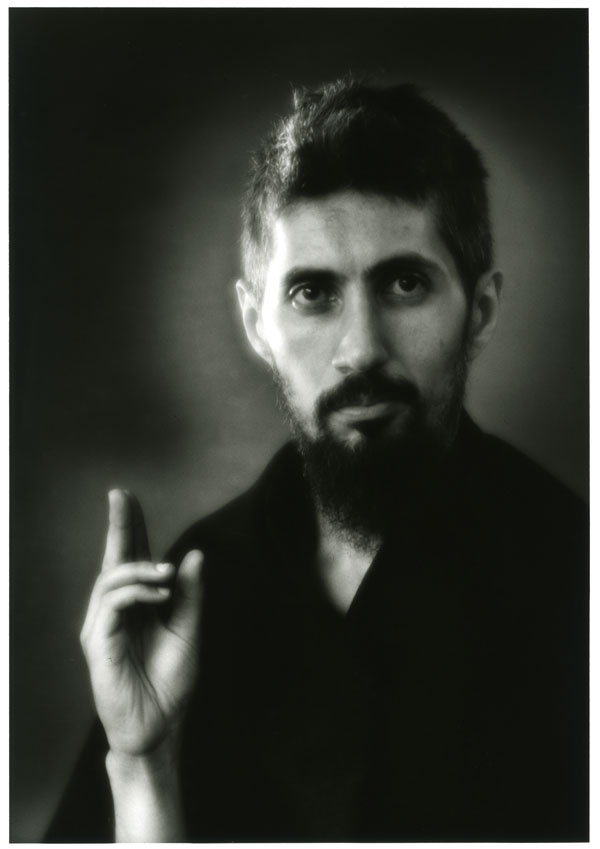

This portrait was taken with an Eidoscope 275 mm f/4.5, manufactured by SOM Berthiot in France, on a 4×5″ negative. This is a historic and very interesting lens in the soft focus category. The camera was a Linhof Technika 13×18 with a reducer back for 4×5″.

The Eidoscope, when fully open, produces a kind of double image, one with good sharpness and the other that adds something like an iridescence, or a halo, to the model if it is properly illuminated.

The image above is a scan of the negative, just as a reference to the naked image. It’s clear that there was an intention or a playful flirtation with the artistic conventions of religious images. But the photo as it was recorded on the negative still needed two interventions to create a truly mystical atmosphere. The first was a load of dodging & burning to turn the picture into an island of light in the midst of darkness.

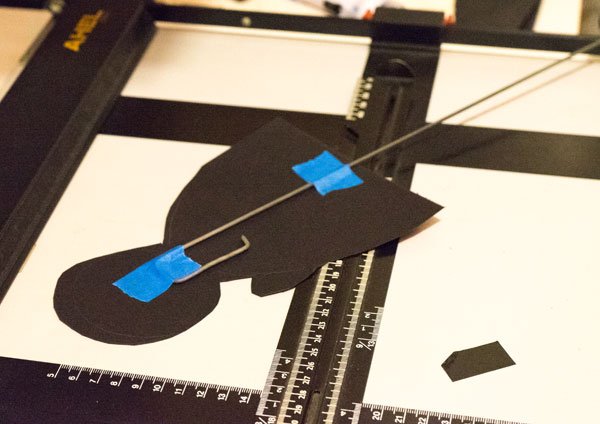

A mask was made to protect the projection of the face and body so that the background received double the exposure. The hand was also “burned” an extra point because, as you can see in the scan of the negative, it was illuminated by a large window at the time of the photo and because it was at a lower height it was much brighter than the face and drew a lot of attention.

By applying the mask during exposure in the enlarger, the effect was to create a kind of aura and the hand became more discreet, allowing attention to be directed more to the face.

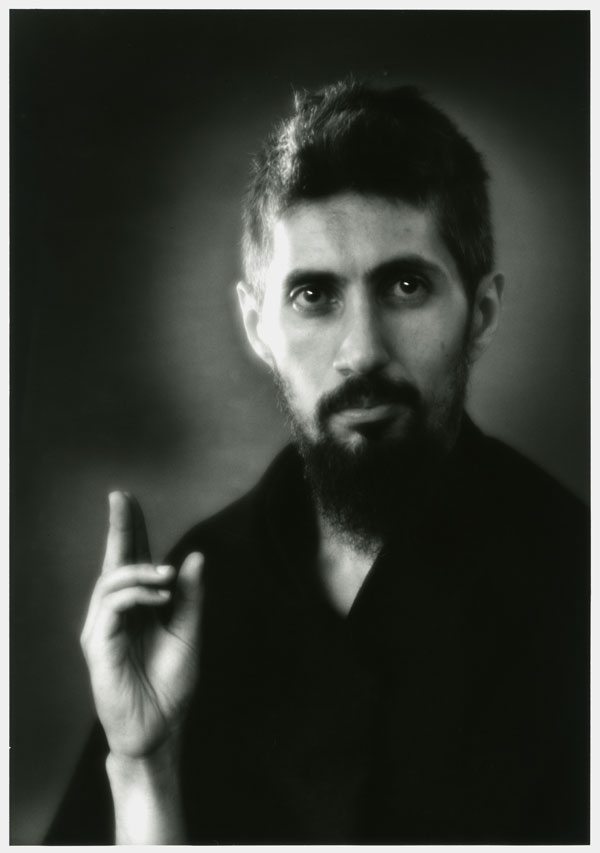

This is now the copy made on Ilford Fiber MG natural gloss paper in 18×24 cm. In order to reinforce his role as a charismatic leader, it was necessary to enhance this prophetic gaze full of wisdom. It lacked more sparkle, it lacked catchlights. Then came the occasional touch-up with Potassium Ferricyanide.

At this point, the photographer wonders if what he is seeing is the same as what other people will see in his photograph. He wonders: is it really that noticeable? Knowing the artificiality of the catchlights, I couldn’t look at anything else when I had the photograph in my hands. They seemed extremely exaggerated and artificial. But perhaps, to an untrained observer, this would just be a “penetrating” look. In any case, I decided on a more discreet effect, probably less glaring and therefore even more convincing to skeptics like myself.

Spot retouching with to pigments

While there’s no turning back, spot retouching by depositing pigments or dyes can be done with much greater effort. Most of the substances used are water-soluble, so if you regret it, you can just wash it off and start again or even leave it as it was. But beware, some residue, even very slight, can remain impregnated in the gelatine even though the material is soluble. It’s therefore good to be careful and not rely too much on the reversibility of the process.

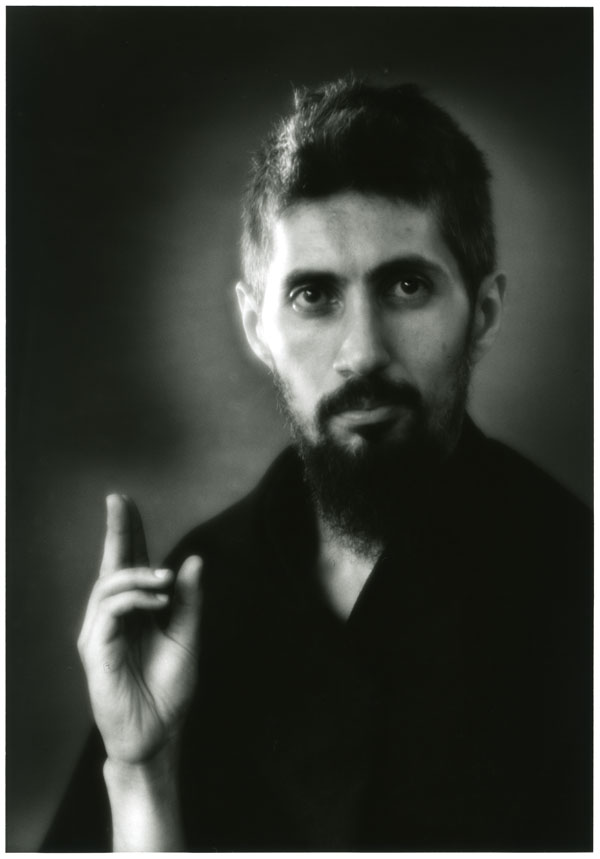

For many years I used India ink, then I bought a set of Peerless Dryspot® sheets. As well as being far superior to India ink, it seems to me that at my rate of retouching they will outlast me. With these sheets and a da Vinci 3-zero brush, made in Germany, I decided to reduce the intensity and shape of the sparkles, the catchlights.

I’m very pleased with the result. This was the final image I had in mind ever since I thought about a possible meeting between the lens, the light, the pose and Rodrigo Silva, whom I’d like to thank. I think that the soft focus of the Eidoscope contrasts well with the sharpness of the glare in the eyes and that contrast, which hindered the understanding of the photo right after the downgrade, was much better utilized with a more discreet and irregular effect. I thought it was a significant gain over the original photo, without stealing the show, as was the case with those exaggerated white dots in the middle phase.

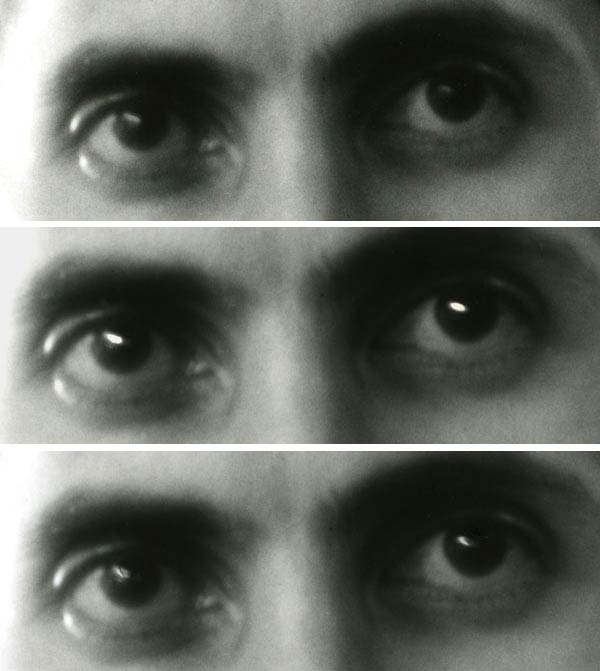

Here’s a detailed comparison of the three phases. Although they’re not meant to be observed with a magnifying glass, I think we can say that catchlighs that aren’t perfect white dots or ellipses look more natural. I followed, or tried to follow, the shape and position of the reflections that already existed and still give an irregularity to their brightness.

Here’s a video to illustrate the table and the workflow. It’s not a standard, but I think it will give you a more concrete reference of how things look.

Corrective touch-ups

The procedure for purely corrective touch-ups is exactly the same. Points that need to be darkened receive the pigment directly, and points that need to be lightened are lowered and then brought to the tone of their surroundings so that they disappear for good. I think it’s practically impossible to lower only to the point of density around the black or gray point. You’d have to deposit the reducing agent in the concentration and quantity needed to bring the point down to a certain shade and stop there. The most feasible option is to whiten and then darken.

In the case of white or light spots that need to be darkened, don’t underestimate their size, thinking that because they are so small any black will do. You need to assess whether it’s a paper with cold or warm blacks and look for the most appropriate retouching. Even sepia copies can be retouched. You have to be patient and test pigments and combinations to find the one that will disappear on the surface of the photo. Black and white has color! Retouching needs to be in the right shade of gray.

The gloss or matte finish can be another variable to consider. In the case of glitters, I think it’s more important that the gelatine is moist. If the pigment can penetrate it, there’s a better chance that the shine will be preserved and there won’t be a matte spot in the middle of a specular surface.

I also recommend that you take a look at the articles on local reduction, the retouching table and retouching black and white negatives.

It’s not advertising, but I’m going to add this printout that comes with the Peerless sheets simply because I thought it was cute that a product like this was being marketed in the middle of 2020.