Triplet Achromatic | Dallmeyer 1862

Dallmeyer was one of the most prestigious firms in the second half of the 19th century and this Triplet, launched in 1862, was its first great success. The story began with John Henry Dallmeyer, born in Germany, where in 1846, at the age of 16, he joined an optician’s workshop in Osnabrück as an apprentice.

The family’s financial situation was comfortable; his father was an educated farmer who was mainly interested in chemistry and experimented with fertilizers. However, according to the laws of Westphalia, only the eldest son inherited the family estate, so the young Dallmeyer, who was the second son, went to work as an apprentice to take care of his own future.

In 1851 he went to London where he found work with another optician called W. Hewitt. But the small firm was soon taken over by Andrew Ross, who was an important manufacturer of telescopes and especially photographic lenses. To give you an idea, the lenses that Henry Fox Talbotused to develop his calotype were supplied by A. Ross.

Everything seemed perfect, the young man who had received a good education, already had some experience in the business and was still ambitious, had gone to work for the best firm in London in the field he had chosen to make his career in. However, when the takeover was rearranged, he was put in a position polishing lenses or something. He resigned and seemed to want to leave the optics business altogether. As he was fluent in English, French and German, he got a job as a business correspondent while still in London.

I haven’t been able to ascertain exactly how Andrew Ross realized his mistake, but the fact is that a year later Dallmeyer was called back and this time to work in the firm’s scientific department as a consultant. In this prestigious position, Dallmeyer began to frequent his boss’s family and, as if to seal the rapprochement once and for all, in 1854 he married Hannah, Andrew Ross’s second daughter.

Another twist: in 1859 Andrew Ross died and left Dallmeyer a third of his fortune and the entire telescope division. His son, Thomas Ross, was left the main part of the business, the Ross brand and the photographic lens division. It was a split that instantly set the two brothers-in-law up as each other’s main competitors, as Dallmeyer quickly opened his own firm the following year and redirected the telescope business towards photographic lenses, which was a much larger market.

The Triplet Achromatic lens

Virtually all photographic optics treatises and period articles are unanimous in classifying the Triplet Achromatic among the best lenses of its time. It was perhaps one of the first general-purpose lens options to emerge since the invention of photography.

There were basically two types of lens in the early 1860s. The landscape lens, an adaptation of the telescope lens, and the portrait lens, which was the Petzval lens. Each had its virtues and flaws.

With his Triplet Achromatic Dallmeyer wanted to find a solution that could shoot both landscapes and portraits. His reasoning was:

About the landscape lens

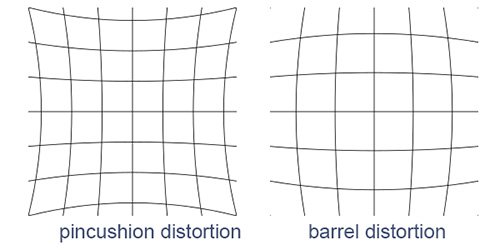

As well as being dark, f/14 f/16 or worse, its problem was barrel distortion, in which the straight lines are curved out of the field of vision, as if puffed up.

The cause: This happens because in these lenses the diaphragm is at the front. When the diaphragm is behind the lens, the distortion happens in the opposite direction and is called pincushion distortion.

The solution: Introduce a second converging lens with the diaphragm between the two, it will be in front of one but behind the other and this distortion will cancel itself out by straightening the lines.

About Petzval’s lens

This lens is very bright but has a very curved field. The consequence is that the image is only sharp in the center and degrades a lot outside of it.

The cause: Because it has two converging doublets, it suffers from marked spherical aberration.

The solution: Dallmeyer introduced a diverging doublet between the two converging ones and this third element has the effect of curving the field in the opposite direction and thus making it flatter.

Dallmeyer’s solution

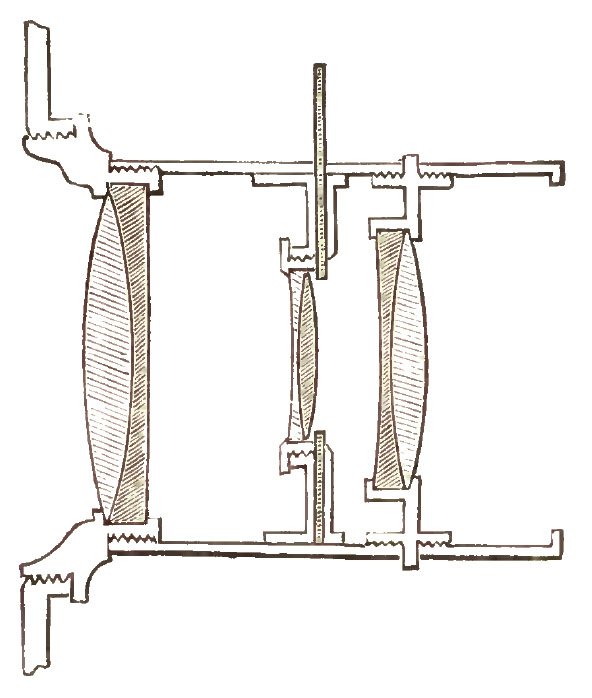

This is the drawing he came up with. There are three achromatic doublets. The front one captures and converges the light but generates spherical aberration and distorts the image. The one in the center, which is practically glued to the diaphragm, is divergent and thus corrects much of the spherical aberration. The third element converges the light more, focusing the image, and because it’s behind the diaphragm it cancels out much of the distortion from the first element. It was a complex lens and therefore expensive, but it offered something like the best of both worlds.

Reception

As has already been said, the lens was a success. It’s interesting to follow the description that appears in Monckhoven’s treatise, published in 1867, and see how he evaluates and compares the Triplet Achromatic with what was available at the time.

The advantages and disadvantages of M. Dallmeyer’s triplet are as follows:

- With the same focal length, it clearly covers a much larger focal plane than the common single lens, but not as large as the new single lens from the same optician, and particularly Mr. Ross’s doublet and M. Steinheil’s periscope.

- It is, within practical limits, free of distortion, but not astigmatism, like theglobe lens [this was a super-wide-angle lens but with f/30].

- But it is free, along its axis, of spherical aberration, which is very valuable when producing animated scenes, portraits and outdoor groups, etc. In this respect, it is superior to the orthoscopic lens [this was the Petzval for landscapes], and especially to the common double lens [this is the Petzval for portraits], whose depth of focus at the same aperture is much smaller than that of the triplet.

- With a diaphragm of one-thirtieth (1/30) of the focal length, it clearly covers an extension of the focal plane whose longest side is equal to its focal length, and this diaphragm opening is sufficient to provide bright images. If the diameter of the diaphragm has to be increased due to insufficient light or any other cause, the sharpness of the image does not decrease (only the extent of the surface clearly covered decreases). This advantage is so considerable in practice that it makes the triplet the most indispensable of all known lenses. The use of the triplet is therefore almost universal.

The Triplet in the collection

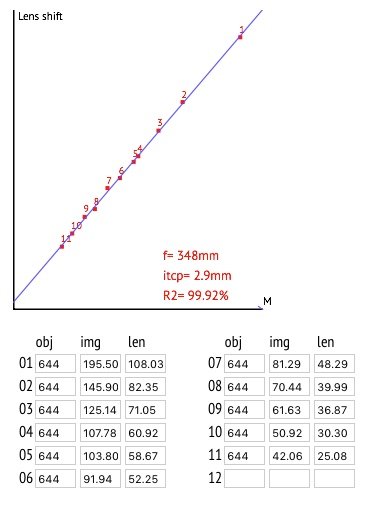

The focal length of this specimen in the collection was measured by linear regression and gave a value of 348 mm, as shown in the graph below.

The aperture was calculated by the focal length divided by the entrance pupil and resulted in f/11. Below it is mounted on a Tornthon Pickcard Royal Ruby Triple Extension 18x24cm.

As for the date of this copy, it has the serial number 3309. There is a file online with the dates and serial numbers, but the table starts in 1863 at number 4500. As the Triplet was launched in 1862, I’m guessing this is from the first year of production.

Above, just to show that it still works, a photo taken with John Henry Dallmeyer’s Triplet Achromatic