Orthoskop | Voigtlander, the second Petzval

– Orthoskop | Voigtlander | 1857/58 –

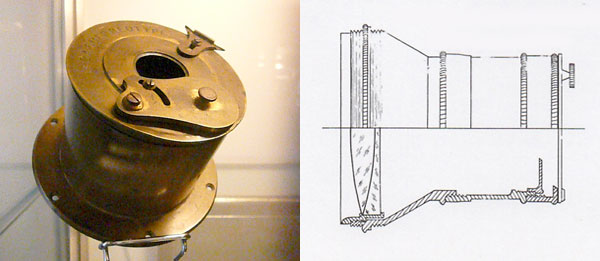

This is the oldest lens in my collection. It came from an antiques shop in Santos – São Paulo, in a shoe box, wrapped in newspaper, with a Dagor 240 mm, a Tessar 300mm and some other non important photographic items. Unfortunately two elements are missing on the rear. Besides that, looks like someone found a good idea to introduce Waterhouse f-stops and made a slit in lens barrel and also added some stuff inside to accommodate the blades. When I inspected it, I found strange the place and the way this cut is. It is not very straight and not at all at quality standards we normally have in this kind of lens. It can be seen in the picture below. Later, I found on the internet a photograph with another of the same kind, in better shape, and confirmed that the cut really does not exist in the original.

About information written on the lens, we have:

Nº 7261

Voigtlander & Sohn in Wien und Brauschenweig

But researching and comparing it was possible to identify it, and indeed, it is a lens very interesting in having even in this deplorable condition. It is a design from Joseph Max Petzval (1807-1891) and follows the same principle of its far more famous portrait lens.

After the invention of photography, the need for faster lenses became very critical as the Daguerre process demanded a lot of light. Exposures were at the level of 10 minutes for a portrait and could go up to 30. Above, we have a lens used in the first daguerreotype cameras and its diagram showing an achromatic doublet and the diaphragm that is in front of the lens so we can’t see the glass that is inside. The picture I took in the French Museum of Photography, in Bièvres, and the diagram comes from the book A history of the photographic lens, from Rudolph Kingslake.

The daguerreotype was an acquisition from the French government made public in 1839. The Society for National Industry Development, in Paris, in 1840, set an award to whom would present a new design for a faster lens. A.F. von Ettingshausen, professor of Physics at Viena University, set about convincing Petzval, 32 years old, who had never worked with lenses before, to work on a proposition. Petzval was a teacher of high mathematics and took over the challenge and, differently from other opticians of his time, developed his lens first in paper, using pure mathematics, before going to build up any prototype. The Petzval lenses were therefore the first ones to be calculated and opened up a the new field called geometric optics. The young man was aided in this endeavour by a team of eight gunners from artillery, skilled in calculations used in ballistics. He arrived to a conclusion in only 6 months producing not one, but two drawings. One was conceived for portraiture and had an opening of f3.6, the other, aimed for landscapes with a broader angle of view and a narrower aperture of f8.7. The portrait lens could only achieve a larger opening with some sacrifice of image circle, or corresponding angle of view. The landscape lens, on the contrary, opened up a wider angle, but in order to not spoil too much image quality, had to compromise with a narrower aperture.

The marathon of calculating light rays trajectories while changing glasses configuration was in 1840. The next year, a first sample was built and presented to the Society for Development, but it ended up losing for another project from a French optician called Charles Louis Chevalier, member of a traditional family in the business of optical instruments, bearing already a history of almost 100 years in the métier. The lenses that equipped the first daguerreotype cameras (sample shown above) were from Charles Louis Chevalier’s design.

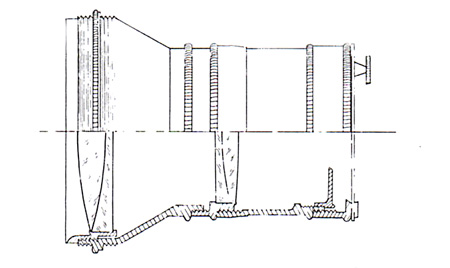

The winning proposition added a second doublet, as it can be seen on the below diagram and was presented under the name objectif à Verres combinés, combined glass objective. The jury preferred Chevalier’s lens, composed of two doublets, as it could be used complete for portraits, or, only in one doublet for landscape, although in each case it was slower and less corrected than the one proposed by Petzval. But they decided to value the flexibility. It is said that the dispute took a turn of French system against German system. Notwithstanding the failure in the contest, history would award Petzval.

Note that again the diaphragm stays in front of the lens, it is on the right side in the diagram below.

Chevalier yet accused Petzval for having copied his idea because, as we are going to see in a while, Petzval also used a landscape achromat with the addition of another doublet (separated in his case) on the rear. Even if that would have any sense in regards to the concept, it was not at all true in regards to methodology, as in this sense Petzval was really paving new ground in optics by using mathematics extensively. We have to consider also that nobody would start something ignoring what was already acquired. I this way, the achromats would be the natural starting point for any further development.

But Petzval did not gave up and presented his two designs to his friend, at that time, Peter Wilhelm Friedrich von Voigtlander, also in the business of optical instruments. Voigtlander immediately notice the value in that new concept and bought from Petzval the right to produce his two models. But no contract was set up, nor patents were involved, nor quantities or agreement time frame was discussed. In the beginning, the landscape option was set aside and only the portrait objective was produced and marketed by thousands. Lacking a patent, other lens makers started to copy or to introduce small variations taking in anyway advantage from the basic concept created by Petzval. Many lenses of that kind, without brand, were produced and can be found still today. Also the main producers do not hesitate to put their names on Petzval type lenses. Among them: Ross e Dallmeyer in England, Hermagis, Auzoux, Gasc & Charconnet, Derogy, Lerebours & Secrétan, Jamin & Darlot, in France, Voigtlander, Steinheil, Busch, in Germany, Suter, in Switzerland, Harrison, Holmes Booth and Haydens in United States (source Kingslake). It did not take too long for Petzval to quarrel with Voigtlander, including a lawsuit, when he realised how much money he was earning thanks to his invention. Voigtlander reaction was to open up a new factory in Brauschweig, Germany, out of the legal reach of Petzval’s complaints. Later, the plant in Viena was closed.

The idea of intelectual property for inventions, artistic work, industrial processes, among other mental work, existed already concept wise, but the ways to enforce the rules were not very effective specially at international level. The subject was new as new was liberalism. The protection given by guilds and class associations during the Middle Ages, focused on “who can operate in this business”, had yet to move to something like “how can one operate in this business”, as liberalism was about anyone being able, in principle, to do or embrace whatever profession or market would please him. In this context, intelectual property, when made public, like the daguerreotype, was immediately recognised as such, freely copied, used and changed. But private intelectual property was yet lacking a structured institutional protection.

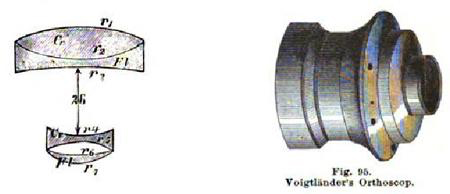

Back to the lenses, all this time the Petzval design for a landscape lens was standing in a drawer, so to say. Seemed that photographers were happy with meniscus and achromats know by the generic denomination “French landscape lens”. But photography evolved and quite soon the need of something better for outdoors was felt. This time, Petzval, who was not in good terms with his former friend Voigtlander, arranged with another Viennese optician, Dietzler, in 1854, to produce his landscape drawing. A new lens was launched in 1856 named Dialyte and it was a success. Voigtlander recognised the design he bought in 1840 and, finding himself in the right of, launched his own new landscape lens under the name Orthoskop, that refers to its low distortion. The lens, now marketed by a powerful house, became even more popular and then it was Petzval and Dietzler turn to profit from what was not theirs: Voigtlander’s name. They left the name Dialyte and adopted also Orthoskop to their own production. Voigtlander obviously opposed to that, but, as in the previous case, there was not much to be done that would prevent them from doing so.

Well, the lens in this post is exactly an Orthoskop, the lens for landscapes designed by Petzval and produced by Voightlander. It was marketed in eight different sizes being one for stereo cameras. At that time, people did not use to talk in terms of focal length, but rather in plate sizes and lens usage, for portrait and landscape, being that a hint of its angle coverage and luminosity. The Orthoskops could do from 7 x 10 cm to 37 x 48 cm, and these latter ones could weight up to 15 kg. This sample must be a 15 x 20, but it is impossible to assert it for sure unless I find another equal in size and complete or well known.

According to the Lens Collector’s Vade mecum, the version produced by Voigtlander was built to accept also the usage of the achromat alone also for landscape work. It is indeed very easy, by removing lens from lens board, to unscrew the rear part. That is very good news for me because what this sample has is exactly the front element. That means that although it is not the complete lens it is, at least, a usable lens. But it is still waiting for a flange.

In regards to date of production, I did not find information like a table relating serial numbers with years. But some leads may help to get closer. For instance, it is known that in february/1861, there was a celebration for the 10.000th lens produced. This one is nº 7261, though certainly before that date. Output at that period was about 454 lenses per year (Vade mecum). Production at Braunschweig started in 1852/53 and they were producing the 4 thousands. The Dialyte that proceeded the Orthoskop was launched in 1856 and it is know that Orthoskop came right after. I also saw in an auction in Germany (image on the left), also an Orthoskop numbered 7723, and it was dated as 1858. I assume that they may have had access to better information than I had. Weighting it all I believe that it might be reasonable to date mine as 1857/1858.

In regards to its design, it is shown in a book Ausführliches Handbuch der Photographie (Complete Photography Manual) from Josef Maria Eder, Germany, from 1893, metioned in an article about a version of the Orthoskop produced by Harrison in United States, on the website Antique & Classic Cameras. Unfortunately I did not find an online version of that book. But I think of researching it in a library next time I go to Europe. The illustration shown is this one:

It fully confirms the lens identity. Looks like it might have a key with all the radius and measurements in the book. That would help to ascertain the right plate size to which this lens was built. The scheme of a cemented achromat in front and an air spaced achromat in the rear is the basic scheme of the Petzvals from 1840. In another lens in the collection it is possible to see a Petzval for portraits. The same pattern may be observed and that it the Cone Centralizateur produced by Darlot, French, not much later than this Orthoskop.

One last comment about this lens is that although there was no concept of telephoto lenses in 1840, technically speaking, this is a telephoto. This becomes even more strange if we think that it is aimed for landscape usage and hence delivers a wide angle of view. But the point is that when Petzval added a negative doublet in the rear, magnifying the image produced by front element, the optical centre of the lens shifted to the front of it. The concept of telephoto lens is a lens that has its optical centre ahead of its front element. This is very useful in making narrow angle lenses to be shorter than their actual focal length. It is very convenient for handheld photography. Well just as curiosity, the Orthoskop was the first telephoto photographic lens.

Flange thread diameter is 73,4 mm. Front lens diameter is 54 mm. Total length is 62 mm.

Actually I just got it apart – bi-concave crown is 5.5 mm thick at edge. flint is 2.5 mm thick at edge. Yours may need to be half that. The diameter of mine are 55 mm for the rear pair.

Id like to discuss this lens with you. I have one coming to me that may be missing the front element. I won’t know until it gets here, but it does have the rear elements.

Hello,

What a coincidence!! But there are several sizes for this lens. Maybe yours is a different one. I know that there is a book from Josef Maria Eder, a photography yearbook from 1893 that has the measurements and specs of all glasses and surfaces for that lens. I could not find it online, but next month I am going to Germany and try to find it in a library. If I ever run across that book, I can send you the diagram. I don’t know if there are suppliers grinding lenses of this type, but if that is possible, and the price reasonable, I would like to try fitting a new pair in it.

Another point: there is an Orthoskop in an auction list at breker.com – it is bigger than mine and looks like it also does not have the rear elements. I wrote them to confirm, so far no answer. You can see their online catalog. It is on page 212 item 853.

Regards from Sao Paulo,

Wagner

Hello Wagner, Yes the lens on Brekker is the same size as mine. 60 cm focal length. I have the pages of Eder’s book with the curvatures for the Orthoskop and Portrait lenses. As you may know, the front cemented achromat is common with the portrait lens. I have a full plate Voigtländer portrait lens of the same era and the front element fitted my lens perfectly so it is useable now. (the focal length is twice that of the full plate portrait lens) Your lens it seems is the half-plate version based on the front element diameter. The focal length of your lens would be, when complete should be 30 cm. approximately.

The rear combination is made from a bi-concave Crown and a concave/convex Flint glass assembled.

The rear pair has four radii. Beginning from the front surface (facing the subject) the first element is a hard crown (refractive index D = 1.517) bi-concave radius #4 is minus 197.55 mm, first surface, rear surface of the crown lens radius #5 is minus 111.76 mm. The second element of the group is a light flint (refractive index D = 1.575) The first surface of the second element, radius #6 is minus 289.7 mm and the rear surface of the second element, radius #7 is positive 79.02. (Which by the way is the same radius as #1 of the front element)

Good luck with finding a lens grinder. BTW I am looking for a Chevalier achromat like Daguerre’s original lens to fit my daguerreotype camera. I am a daguerreotypist in Toronto.

Mike

Wow Mike, that was a big surprise. Thank you so much, this specific book from Eder is really hard to find. Big lens is yours, I have no camera for 60cm focal length. 360 mm is my limit with a Thornton Pickard 18 x 24 cm.

About your search for a Chevalier, do you know the Bièvres photo fair in France? There might be a good place for searching a Chevalier lens. All French lenses indeed. I bought there a Darlot, one Derogy (both 13 x 18 cm) and also a Hermagis for 20x25cm. I have a post in my site about this fair (references > places, it is the only post so far in this section). I’ve been there a couple of times and intend to be there again next year.

Nice that you do Daguerreotypes, I bought once an ampoule with Bromine thinking of trying it out. Most beautiful red I ever saw. But afterwards I researched the safety instructions about this reagent and never had the courage to open it up. It is still in the glass. From time to time it comes up to my mind that I need to find a correct way to dispose it before I die.

One question about the measurements you kindly sent me. Is there any info there about thickness and airspace between them? I found already on the web some companies that make customised lenses so I will consult them. Thanks again.

Best,

Wagner

There is no metal spacing ring, like used in the portrait lens so the air space is determined by the two radii face to face. I cannot get my rear cell apart but the combined thickness seems to be about 5 mm with a nearly knife edge for the last element as seen in the picture you have. On my lens the brasswork is different with an internal treaded retaining ring to secure the lenses. I guess if you measured the gap in your rear mount and added a half a mm to ensure a tight fit that will be about as close as you can get. I think if you get the curves right, the thickness should not make any difference…within reason.

If you get a quote for the glass grinding, let me know the cost. I think I can get the formula on the the Chevalier from an 1844 French manual. Finding one I expect would be very very expensive.

Don’t open that bromine!

I was kindly sent a pdf of an 1899 edition of Eder’s book by Dan Colucci from Antique & Classic Cameras. If you drop me an email I could send it to you.