The Darlot firm is among the oldest manufacturers of photographic lenses in France. Its history begins with Jean François Jamin, who had been manufacturing optical instruments since 1822, even before the announcement of the Daguerreotype in 1839. When this happened, Jamin immediately began manufacturing lenses for the first photographic cameras and was an official licensee of Louis Daguerre to produce equipment under his seal. He launched a highly successful concept, the Cone Centralisateur. Later, Alphonse Darlot became a partner and in 1860 took over the company alone when Jean François Jamin retired. Initially, the lenses bore the name Jamin Darlot and after 3 years simply Darlot.

This one is engraved B.F & Co. and allows us to identify it with something much more recent, possibly from the 1890s. It is a distributor of Darlot and Voigtlander equipment based in Boston, USA. It was common at that time for an important distributor to negotiate with its supplier to add its brand to the products it sold.

This is the cover of the 1890 catalog. We can see that the main focus is on Voigtlander lenses from Germany, which are undoubtedly more prestigious than Darlot. In general, since the beginning of photography, English and German lenses have always been well-known and priced well above their French counterparts. In terms of quality, this may not be the case for the most common lenses. But it is undeniable that in terms of innovation, French firms were generally more followers than pioneers. Benjamin French claims to have exclusive distribution rights for both brands in the United States.

The design of this Darlot is the classic Petzval lens, developed by the Austrian mathematician in ~1840. It consists of a front doublet glued and a separate doublet at the back. The role of the first is to converge the light captured by the lens and the second aims to straighten the focal plane, but it does so only partially. As a concept, it is a lens full of aberrations, but it was/is extremely successful because it is bright and works very well for portraits. It gives a very sharp image in the central part and degrades quickly towards the periphery. Practically every manufacturer of photographic lenses offered Petzval-type lenses in their portfolio. This was the rule from the 1840s until the beginning of the 20th century and today they are still produced as “alternative” lenses to the mainstream.

At the time of its production, this was such a common lens, with over 50 years of history, that it doesn’t even have a serial number engraved on it. It was probably like a commodity for Darlot. It uses traditional Waterhouse-type inserts as a diaphragm, but none came with this sample. However, this is very easy to 3D print as long as you calculate the diameters of the holes.

On the page where Benjamin French introduces the Darlot lenses in his portfolio, he explains that he decided to engrave his initials because of the many counterfeits that were being offered on the market. As if counterfeiters couldn’t also engrave B.F & Co. He comments that the “extremely low price” of Darlot lenses should not be the only reason to buy them, because in terms of “speed and general excellence they are equal to the best lenses”… with the exception of the Euryscopes, which he also distributed, from Voigtänder & Son’s.

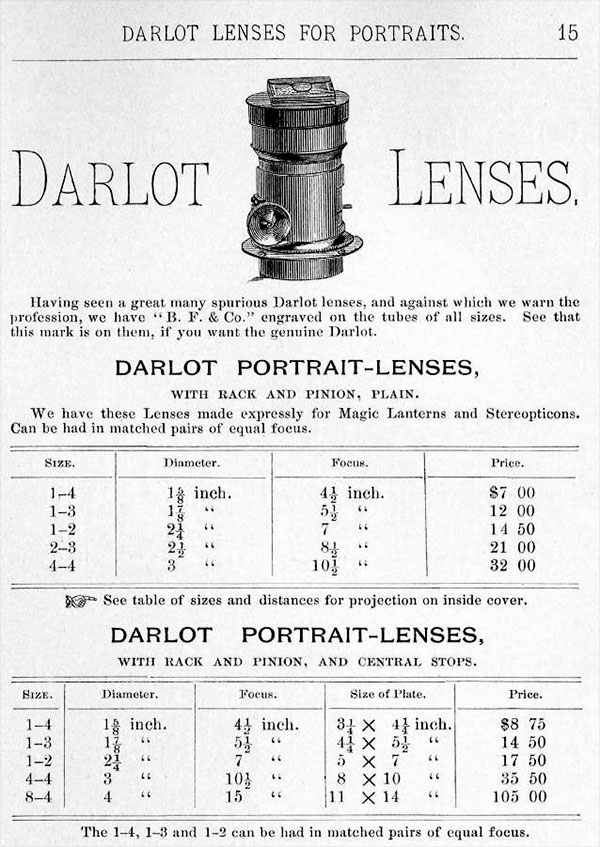

The sample from the collection appears in the second table in size 1-3. Lens diameter 1 7/8″ or ~48mm and focal length of 5 ½” or ~138mm. The recommended format for the film or plate is 4½ x 5½”. But this seems a bit exaggerated to me. Since the image loses definition towards the edges, it ends up being very subjective to say what format the lens really covers. What I noticed is that with it wide open on a 4×5″ film, towards the edges the image is already really blurry.

The total length, including the lens hood, is ~110mm. The body diameter is ~62mm and this allows, with an 80mm flange, to mount the lens on many 1/4 plate cameras, equivalent/compatible with 4×5″ or 9×12 cm.

This was the first photo I took with it. It was in 4×5″. There is a fall-off in this format but it is not that pronounced. I did a burning to highlight the swing and also tilted it a little counterclockwise to give it some movement. You can see a certain swirl formed in the background. That is typical for a Petzval lens. It is important to note that it is not only the loss of focus that takes away the background definition, in this case it is the aberrations, spherical, coma, astigmatism, distortions, etc., which this lens design would not be able to suppress.