Musée Nicéphore Niépce

The very first photograph

Although there is no doubt that the Daguerreotype, announced to the world in 1839, was the first commercially successful photographic process, it is accepted that the above image is the oldest photograph we have today. That is Nicéphore Niépce’s Point de vue du Gras à Saint-Loup de Varennes – 1827. Today, it is in Austin University – Texas – USA. The image on the left is how the plate looks like, the one on the right is a rendering of that image aimed to an easy reading, without metallic reflexion and far more contrast.

The Museum Nicéphore Niépce, in Shalon sur Saône, 4/5 hours driving/train southeast from Paris, gives a full account of the last steps that led to the invention of photography. Nicéphore is until today constantly presented as unjustly relegated to a minor role in photography development while names like Daguerre, Talbot, Herschel or Wedgwood are considered the true innovators. That is an old claim. In 1867, Niépce biographer Victor Fouque published La vérité sur l’invention de la photographie, Nicéphore Niépce, sa vie ses essais, ses travaux (The truth about the invention of photography, Nicéphore Niépce, his life, his experiments , his works). The title openly conveys this air of denouncement, of some evil or conspiracy against Nicéphore.

Visiting the museum we understand Niépce’s contribution and it becomes clear that it was indeed pivotal. But that does not dimmish Daguerre’s part nor charges him as being guilty about his efforts to call the new process after his name alone. More than that, the parcours invites visitors to think the advent of photography from a very broad perspective instead of disputes among its forefathers. These personal motivations, and idiosyncrasies are better seen as surface movements over deep social changes that were undergoing in society. Fortunately curators had that broader view in mind while setting up the whole museum concept.

The Museum

The museum is located at the very heart of Chalon sur Saône, city where Nicéphore was born, and it faces the Saône river in a very beautiful spot having an isle just in front of it. There we see a little garden with an iris and Niépce written with flowers.

The first room, photography and its forms

The first room shows photography from many different perspectives. As we read in their website: “The ambition of the musée Nicéphore Niépce is to explain the basics of photography from its invention by Niépce up to today’s digital imagery”. That goal is pursued by linking equipments, history, images and key players in photographic industry: public, photographers, manufactures, press, entertainment industry, etc.

First piece is a large studio view camera. It demonstrates the image formation principle that can inspected on the ground glass. The screen on the wall, right of the picture, is also an image formed by lens facing the street on one of the museum sides.

Here is a copy of the first photographic camera designed for portraits using the newly created Petzval lens with aperture ~f4. The original was built by Voigtlander in Wien. Just a few survived till our days.

The complexity of image making in the sense of: what is likeness after all? What would be a true to life simulation of a visual experience? is raised when we see attempts to obtain, for instance, three dimensional images. The above machine was able to rotate around the subject and take photos from different angles. Those pictures were later assembled in one single flat support and a layer of micro prisms allowed only one image to be visible at a time, according to the angle of view, giving the impression that the viewer was walking around a real object. The effect is amusing but not convincing. This was later used for souvenirs and other popular and cheap gadgets.

Landscape panoramic photography was another wonder as one could browse the details and embrace an angle of view bigger than what the human eye can. The equipment developed for that purpose was normally based on a rotating lens and samples of cameras are showcased

The relation of still photography and cinema industry is remembered through the specialized press that emerged after the first World War and contributed tremendously in setting up new aesthetic and behavior standards becoming a real mythological repository of our era.

Leica, the revolutionary camera designed by Oscar Barnack and launched in 1925 is featured with some accessories like it auto-focus enlarger.

Another icon of photographic industry, the Rolleiflex, is shown with some contact prints, as one of its strengths, as a medium format camera was, for amateur use, the possibility to dispense with the enlarger and produce hight quality prints for a family album.

The role of film manufactures in fueling masses’ desire to record their memories is also remembered in this panel featuring a picture of a retail photo counter, press advertising, plus Kodak and Agfa panels used to indicate a points of sales. The explosion of consumer photography can’t be seen as just an industry satisfying a demand for pictures. It was for sure a complex movement involving many different aspects of technology, retail structures and the shaping of an image driven culture in its values and self understanding. Our digital era is probably yet a deployment of such seminal transformation.

All in all , these are just some highlights and this entry room works as “food for thought”. Of course is does not intend to offer an analytical view of what photography meant for our culture but it opens several doors and gives several leads one can follow and reflect upon.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce

Going up to the first floor, we discover how it all began. Nicéphore Niépce’s was born into a wealthy family of bourgeois origin, but already possessing some privileges that only a noble family would normally have. His father was a court lawyer, advisor to the king, and in charge of government affairs in Chalon-sur-Saône. What attests in practice to their noble status is the fact that the family had to disperse and go into hiding during the French Revolution. Nicéphore himself chose a military career in the army – this was shortly after his father’s death in 1792 (he was 27 years old). His brother, Claude, did the same in the navy. It was part of a strategy to distract attention from the family’s aristocratic connections. But neither he nor his brother had any military vocation, and both abandoned their careers when things cooled down. Both returned to Chalon to live in the comfortable house where they were born. The revolution took a large part of the family’s fortune, but what remained was still enough to continue living a good life as part of the Chalonaise elite.

What is interesting in this brief recapitulation of some facts from the life of Nicéphore Niépce is to highlight how he embodied all the ambiguities of his time. He, as a bourgeois, defined himself as an entrepreneur. However, a life as a “businessman” was something he truly could not bear; it would be too mundane for someone as refined and cultivated as he was. The military career, the most deeply rooted of all aristocratic vocations, was also not his talent. Becoming a dilettante living in isolation was therefore his choice. This would keep him away from universities, away from the court, and away from business centers, away from all kinds of competitive environments, quite in keeping with his aversion to social life. His choice was for a solitary, semi-scientific pursuit of new technologies, which would never be fully developed – to this pursuit he dedicated his life. We discover in Nicéphore Niépce, much more a man of Romanticism than of the Enlightenment.

Chambre de la Découverte

As we climb to the museum first floor, there is one room dedicated exclusively to Niépce’s works. He was attracted to the realm of images when he learnt about lithography. The process was recently invented and in 1810 the first treatise on the subject was published in Stuttgart. That triggered a quick dissemination throughout Europe. Georges Potonniee, is his Histoire de la Découverte de la Photographie (p.84) gives a certain fashionable touch to the novelty: “in 1813, cultivated people were doing lithographs, Niépce like the others. And that discovery, which he saw as a marvelous one, made upon him a deep impression”. Interested as he was about industrial processes he set himself the problem of arriving to a drawing spontaneously made by “natural forces”. That was the driver and first conception of his project.

A preliminary success was reached using a coating of Bitumen of Judea as a light sensitive surface over a metal plate. Artists used to cover copper plates with bitumen and later scratch it with a sharp instrument exposing the metal. Next, they used an acid etching the drawing. Last step was about removing the bitumen, inking the plate and stamping it on paper, reproducing this way the drawing. So Niépce modified this process by observing that the Bitumen becomes less soluble after the action of light. Instead of scratching, he placed engravings printed on paper over the bitumen coating and expose it to sunlight. The white paper was turned transparent through the application of wax and oils. The printed part worked as a barrier to light. Next, he washed out the unexposed parts that were still soluble and the exposed remained as the drawing etched by light. He called this process Heliography.

On the left we see the well preserved sample of that phase as shown in the Nicéphore Niépce Museum. That is from 1826, made over a pewter plate, and represents Cardinal Georges d’Amboise. On top is the backlit paper engraving, in the middle the metal plate and at the bottom a final print. Niépce sent it to be printed in Paris by the engraver Lemaître.

At this time he was already very close to something that could have a commercial application. Foto-mechanical reproduction of images could be a new business. But the light filtered by a hand made drawing was not the light he had in mind. So he continued to the next step that was about using a camera obscura.

Above, one of the Camera Obscura used by Niépce. He expected a sort of print-out effect and so drilled two holes, normally closed with corks, in order to allow him a real time observation of image development. He used a Wollaston type lens that was a simple meniscus offering about f11 or f16, that means, not bright at all. His first surviving success in capturing an image with a camera obscura is the image that opens this article, the Point de vue du Gras à Saint-Loup de Varennes, it dates from 1827 and it demanded an exposure of 12 hours. Niépce knew that this exposure time was not practical and so decided to go after other light sensitive substances to replace the Bitumen. It was known, for instance, that some silver salts were darkened by the exposure to light. The problem was not actually about getting an image but rather on how to fix it, how to remove the parts of it that were not exposed. The samples showed something when removed from camera but the shadows continued to blacken due to the action of ambient light.

Niépce experimented with a lot of different substances, particularly he had a great hope about the use of phosphors but that never yielded any good result. If we think of combinations of supports like cooper, pewter, silver… light sensitive substances like bitumen, phosphore, silver salts, iodine, development or cleansing baths in different oils, acids, whatever, plus different timings and concentrations, for all these processes, we can infer that Niépce employed thousands and thousands of hours in his trial and error experiments.

By the end of the twenties he was convinced that the quality of images produced by his camera obscura was an issue. In 1826 he asked his cousin, who was going to Paris, to bring him several optics from Vincent and Charles Chevalier, well know opticians at that time (Fouque p117). That is how Charles Chevalier was acquainted with the nature and results from researches performed by Niépce, and it seems that was Charles Chevalier who put him and Louis Daguerre in touch.

They started a collaboration but it didn’t last long. Niépce died in 1833 at the age of 68, and his son Isidore took over his part of the contract (Daguerre was then 46 years old). But other developments were driven by Daguerre, and, as we know, his name alone would be primarily lauded with glory for the discovery of photography.

Daguerre’s trail, from that point onwards, kept part of his exchanges with Niépce. He continued, for instance, with the idea of using a metallic support. This was a sort of inspiration from etching, as it was pointed above, so he was using a metalic matrix. The idea was simply replacing manual labor by the action of light. Their research was very important, and the Daguerreotype, in particular, was a huge commercial success. However, it was soon abandoned in favor of negative/positive processes using paper/paper and glass/paper as supports.

In case you are interested, there is a more detailed account of the Daguerreotype process development, starting with Niépce’s contribution, in this article: The contributions of Niépce and Daguerre.

The visit continues

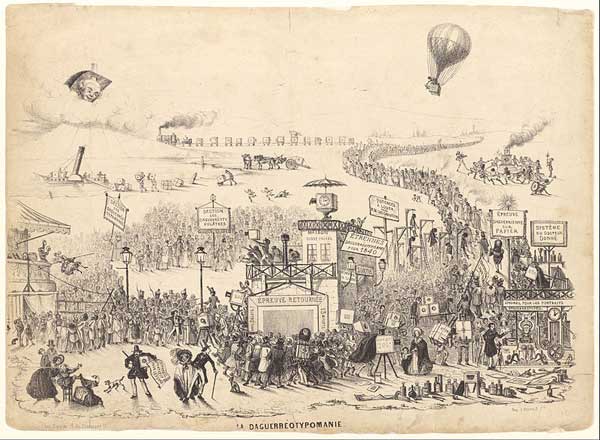

As we proceed to the following rooms we have hints of the quick changes that happened right after the discovery, during the first decades of photography. Many pictures are shown in new techniques and it is interesting to note how sitters’ attitude were changing as they could be at least more relaxed with shorter exposure times. It was a whole new imagery and new ways of recording individual and collective memories.

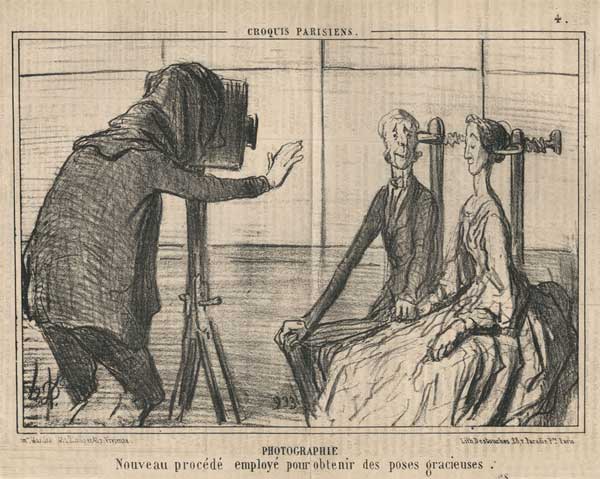

Some very famous lithographs and other printed material are also on display.

Above the iodine sensitizing box the first step in sensitising a plate for a daguerreotype.

At the center, the big wood box was used for development of the image in mercury vapor.

Developing tank for roll film before the spiral and a safe light before electricity.

A large room features temporary exhibition on photography and contemporary art.

***

I visited many museums related to photography, but the Musée Nicéphore Niépce in Shalon sur Saône is the one that by far I liked the most. It is like an open discourse, exactly what I think a museum has to be. Not a singleminded view edited by a curator, nor a collection of antique inventory indifferently amassed throughout the years. I vividly recommend to anyone a visit.

Note: This article originally had a longer discussion about the life of Nicephore Niépce, his contribution with Louis Daguerre, the invention of the Daguerreotype and yet some considerations about the relation between photography and modernity. In jan/2017, that was split and the focus of this article is now on the museum itself. There is now a separated article about the The contributions of Niépce and Daguerre. and yet another one about Invention of photography and modernity.

Sir,

It’s an excellent and informative article.

Congratulations and the best wishes.

Aké boli rozmery prvých fotografií?

The camera made by Voigtlander, specially for the Petzval portrait lens, was intended to make circular daguerreotypes with 91 mm diameter. Later what became a market standard was a rectangular plate about 16 x 22 cm (6,5 x 8,5 inches). That was called the “whole plate” and also fractions of it were available 1/2, 1/4. At one point in time, the continental European standard and near size became be 18 x 24 cm and the English/American 8 x 10″, and that remains until today. It is hard to find in literature references of those sizes. Maybe It was like taken for granted that everybody was aware of them.

I was wondering when did you publish this article. I need to reference your article in my photography assignment. Thank you.

Hello, thanks for visiting my website. This article was published in July/ 2017. Best WL