Euryscope | Voigtlander

The story of this lens would be worthy of a novel or perhaps a feature-length film. But not about optics, which would perhaps be too technical and boring for the general public, but about family relationships. Although a little out of place on a website primarily about photography, the point of going into such details is that these, let’s say… anecdotal elements, give us an idea of the spirit of the time and remind us that behind these technological innovations there were still human beings working. This may no longer be the case in the near future.

Euryscop is a lens, or rather, a family of lenses that is divided into several series, manufactured by the Voigtlander company in Braunschweig, Germany. Voigtlander’s history dates back to 1756, much earlier than photography (1839). Its initial production was mainly focused on scientific and measuring optical instruments.

It was the founder’s grandson who introduced the first lens designed specifically for photography, the Petzval lens, into the company’s portfolio. This was shortly after the Daguerreotype was announced. A task force led by Viennese mathematician Josef Petzval calculated what would become his famous portrait lens. Since the university collaborated closely with industry and vice versa on scientific matters, Petzval handed over the design to the Voigtlander firm to produce a prototype. But Peter Friedrich Wilhelm Voigtlander produced not only the prototype but, over the following decades, thousands of copies for sale. When the mathematician realized the huge business he handed over to his friend without getting any share for himself, the relationship between the two soured and ended in court, which ruled in favor of the industrialist. This story is told in detail in this other article: The Petzval Lens.

Let’s jump to the 1860s when Voigtlander was one of the leading manufacturers of lenses for photography, with a recognized reputation for quality and a great deal of respect for its history. It was still Peter Wilhelm Friedrich von Voigtlander, born in 1812, who ran the company and insisted, as often happens with those who achieve great success in their youth, on continuing on the same path as before. In that case, of having as its flagship the same formula, the same lens, as 20 years ago: the Petzval lens.

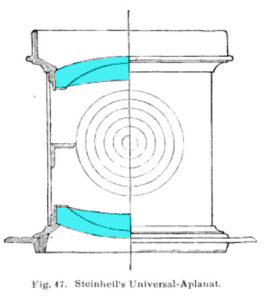

In the meantime, firms such as Dallmeyer in London and Steinheil in Munich had introduced a new optic with two symmetrical doublets in 1866, which would become the concept for the first general-purpose lenses, paving the way for more compact cameras and handheld photography. Another important firm, Busch of Rathenow, was making excellent lenses based on the Petzval concept at a third or even half the price of Voigtlander.

Peter Friedrich felt the competition, and his Petzval sales declined. To adapt, the firm returned to the production of scientific instruments, such as telescopes, and also closed the factory in Vienna and moved its headquarters to Braunschweig, where a branch had been operating since 1849. Peter Voigtlander refused to invest in new designs and insisted on the old formula of which, by 1862, he had already produced about 60,000 units, according to Kingslake.

Peter Friedrich’s connection with Braunschweig goes back even further than the opening of the branch in 1849. In 1845, Peter Voigtlander married the widow Nanny Zinken (1813–1902), whose birthplace was Braunschweig. This probably had some influence on his decision to open a branch in that city. But what is interesting here is that from her first marriage Nanny Zinken brought Peter Friedrich a stepson, Hans Zincke Sommer, born in 1837. Hans Sommer is the designer of the Euryscop lens.

The most curious thing is that when searching for his name on the web, I found a musician named Hans Sommer, a renowned composer in his time. He was so active that he even founded an association with Richard Strauss to protect musicians in various matters, such as copyright, for example. It is still possible to find recent recordings of his compositions for sale on the web. My first reaction when I found this was: no, that is not the Hans from Euryscop. But then, after checking it out… yes, it is him. It turns out that his stepfather, although the young man already showed an inclination for music and wanted to pursue a career, did not accept the idea of an artist stepson and instead sent him to Göttingen in 1854 to study mathematics, where he completed his doctorate in 1859.

Returning to Braunschweig, Hans Sommer began his apprenticeship on the “factory floor”, which meant hard work on machines such as the lathe, for example. It was a disappointment. The young man had no talent or ability for manual work. Corrado d’Agostini hypothesizes that this was another reason for Peter Friedrich’s “lack of respect, if not open hostility, towards his stepson”.

Agostini even considers that the preference for his son Friedrich Ritter (1846-1924) over his stepson may be understandable. But what is difficult to make sense is how the patriarch, who was also an excellent optician and businessman, could ignore, especially with the firm in difficulties and very active competition, the many interesting and innovative projects that Hans Sommer submitted for his approval? In his autobiography, Sommer writes: “When Voigtlander saw lenses produced according to my designs, he would say that their obvious advantages were not significant enough to merit abandoning the old system.”

Meanwhile, Hans Sommer had become a highly respected scientist in academic circles. He taught mathematics at Braunschweig’s Technische Hochschule (1859–84), and was its director from 1875 onwards. Ironically, given his stepfather’s disdain for and clear preference for his nine-year-younger brother, Friedrich Ritter Voigtlander, Hans helped shape him by tutoring him in mathematics and physics, preparing him for the successor to his father’s firm.

In fact, from 1871 onwards Friedrich Ritter took on more and more responsibilities in the firm, however, as his father still insisted on having all the final decisions, it was not long before the two came into conflict to the point where Friedrich Ritter threatened to leave to open his own business.

In 1876, Peter Friedrich Wilhelm von Voigtlander definitively and completely handed over control of the company to his son. In 1877, Voigtlander’s first aplanatic lens was launched. It was about 10 years behind its competitors. It was later given the commercial name Euryscop. Hans Sommer had designed this lens in 1872, but its commercial launch had been hold on by his stepfather. When it was finally put on the market, it was a huge success and gave Voigtlander a new lease of life. Peter Friedrich Wilhelm von Voigtlander died a year later, in 1878, at the age of 66.

Another twist in this story is that despite the close collaboration in the early years and even the recognition of his work, we might have expected that Hans Sommer’s relationship with his half-brother would have been very friendly when the latter took over the firm. Instead, Friedrich Ritter became increasingly hostile and authoritarian (Agostini) and in 1882 they broke off for good. But at this time Sommer was already mainly dedicated to the university where he taught and it was from then on that he was able to return to his youthful passion, which had been music. Brilliant as he was, he was also able to leave his mark on posterity in this area.

The Euryscop Série IV #2

From the serial number, according to the VadeMecum, this is a lens manufactured in 1888. At that time it was not customary to include the focal length engraved on the lens. Photographers referred to the material published by manufacturers and distributors.

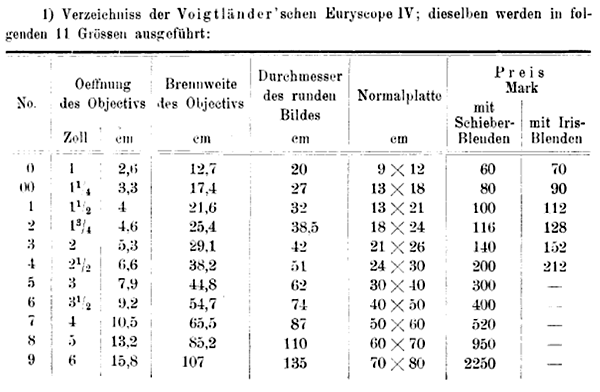

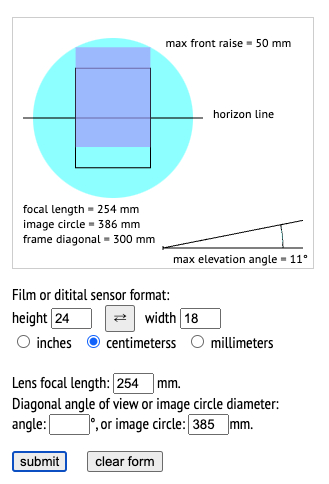

This table in the book Ausführliches Handbuch der Photographie by Josef Maria Eder from 1893 shows that Series IV #2 should have a focal length of 25.4 cm and should cover 18 x 24 cm. The diameter of the image circle is 38.5 cm. Since the diagonal of 18 x 24 cm is 30 cm (easy calculation here: Minimum image circle for a given format), it allows some freedom of movement. For example, a front raise can go up to 50 mm in portrait format.

This places the horizon line at about 1/3 of the frame and allows you to get the perspective right in many situations. This calculator is online and available here: Front raise and horizon line.

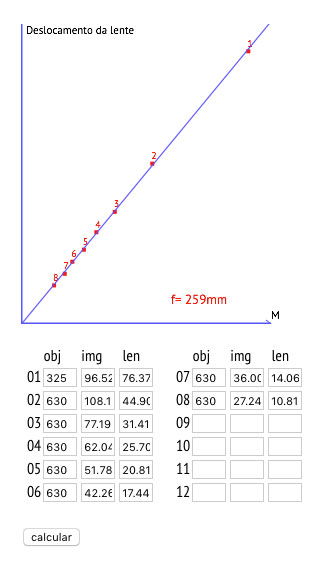

The focal length measured by linear regression of magnification gave a slightly different result, as seen in the graph below.

259mm instead of 254mm in the manufacturer’s table. But this is absolutely normal and is within the margin of error of the lens and the method.

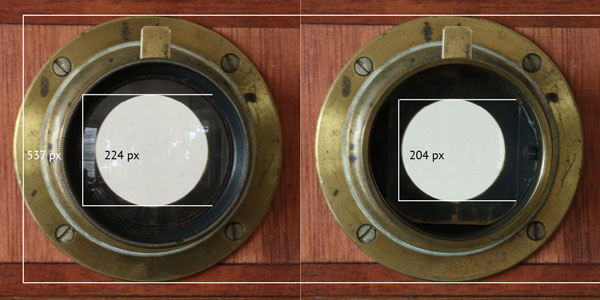

The lens came with only one Waterhouse-type diaphragm. To make the others, it was necessary to calculate how much the front element enlarges the actual diameter of the diaphragm. I usually do this by photographing the lens with and without the front element. I use a longer lens to reduce distortions and then compare the aperture sizes by measuring the pixels in the image.

In the photo above, on the left with lens and on the right without lens. Dividing 224 by 204 gave me the factor 1.098 which allowed me to calculate the actual diameters of a set of diaphragms to complete what came with the lens. According to Eder, the Euryscopes of the IV series have a maximum aperture of f/5.6. Dividing the focal length 254 mm by 5.6 results in an entrance pupil of 45 mm. Dividing 45 mm by the factor 1.098 results in 41 mm which is approximately the aperture of this lens without any Waterhouse.

By doing this I found out what other diameters I needed and by drawing them to these measurements I was able to have a set of diaphragms laser cut as shown in the figure below. A complete and detailed description of how to find the aperture of a lens; or how to find which diaphragm diameters result in which apertures, is available online at this link: Measuring the aperture f in lenses

The brass Waterhouse came with the lens and corresponds to the f/8 aperture. The others are in blackened carbon steel and give the sequence up to f/64.

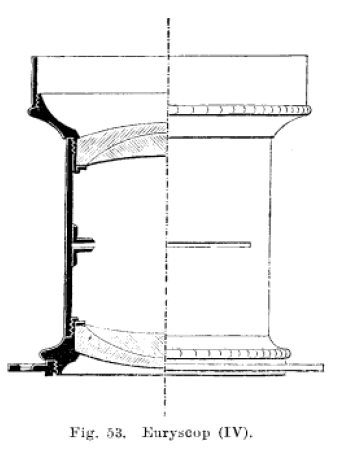

Above is the drawing of the lens reproduced from the aforementioned book: Ausführliches Handbuch der Photographie by Josef Maria Eder, from 1893. The symmetry is clear and it also shows that they are two relatively thin doublets. The viewing angle is 70º.

Also according to Eder, after the launch in 1878, several other versions were designed based on the same concept. They were developments launched by Friedrich Ritter von Voigtlander taking advantage of the new glasses from the city of Jena, Germany.

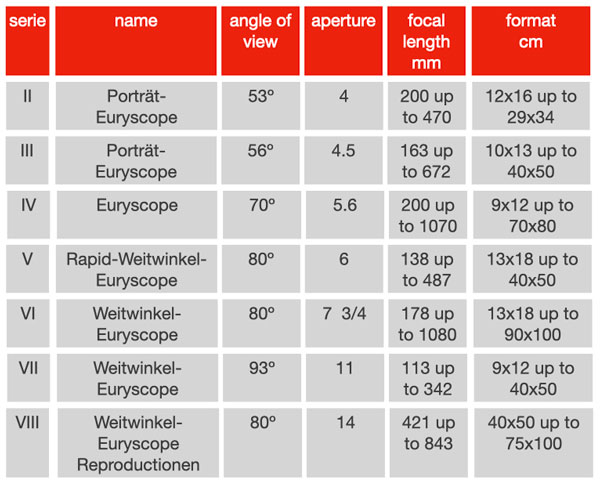

This table, made from information in the aforementioned book by Eder, from 1893, shows all the series that were developed by Friedrich Ritter Voigtlander based on the drawing by Hans Sommer.

It was common for series based on the same concept to be divided into types of usage. At the top, we have two series for portraits that prioritize aperture and sacrifice a little bit of the angle of view. Series IV is in the middle in everything and would be a general purpose lens. From there, we have two wide-angle lenses (weitwinkel in german) of 80º, one faster with f/6 and the other with 7 3/4, practically f/8. The next, series VII, is the one that achieves the widest angle but sacrifices more aperture, stopping down to f/11. Finally, a lens for graphic arts (Reproductionen), whose smallest format starts at 40x50cm. The number of different lenses that were offered is impressive. Multiplying the series by the number of focal lengths available for each series, we have 52 Euryscope options!

In use, the Euryscope shows that it is an excellent execution of the Aplanat or Rapid Rectilinear concept. Lens design normally started from a concept, a certain number of elements or simply “glasses”, each with its own role. This role could be to give the set the most pronounced convergence power, another glass or group will straighten the focal field, another will correct aberration a, b or c, etc. etc. Given this concept, which usually came from an insight of an optician with a lot of experience and intuition, then comes the rendering part, of calculating the best ways to bring the concept to life. This part involves a lot of mathematics and will tell you whether or not the initial concept can make a good lens, within the intended use and within the budget and complexity that it may present.

That’s why not all Aplanate or Rapid Rectilinear lenses are the same, and that’s what made the Euryscopes so successful: they were right on the edge of what could be extracted from the concept of two cemented doublets and symmetrically positioned in relation to the diaphragm. The next evolution was the creation of the Anastigmatics by the end of 19th century.

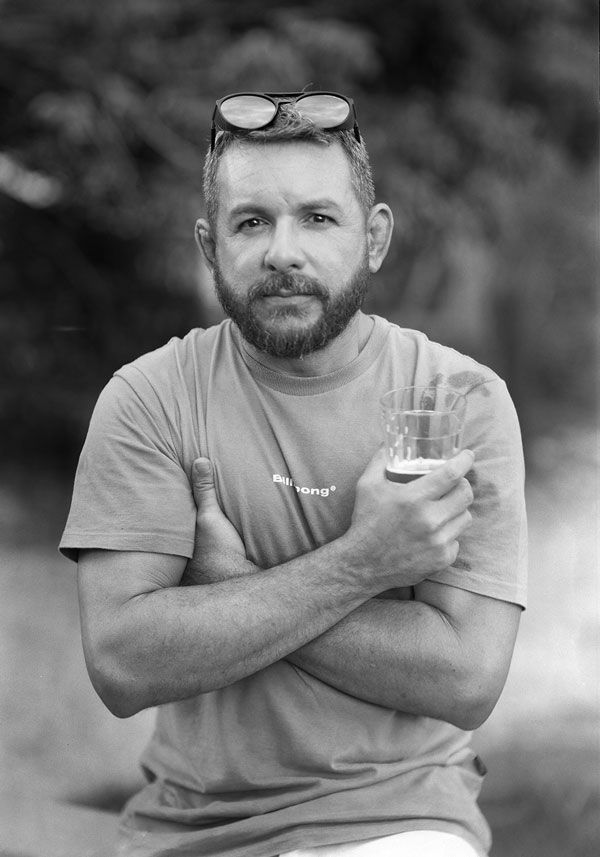

Finally, two photos taken with this Euryscope IV nº2. Although it covers 18 x 24 cm, I mounted it on an ICA camera called Excelsior, which is 13 x 18 cm. With this lens I use a studio shutter, which does not offer any high shutter speeds, but with a View Camera, I end up choosing subjects that are not exactly “action”.