Nikon F | Nippon Kogaku K. K.

Japan’s incredible feat

Nikon played a fundamental role in establishing the Japanese photography industry as a world leader in the sector from the 1960s onwards. For a period of 150 years, Europe, especially the Germans, dominated the market for production and innovation in cameras and optics so completely that until the 1950s, even with the turmoil caused by the Second World War, it was unimaginable that the next chapter would be written by companies from lands so distant and so distinct from the Europe/United States binomial.

The feat is even more remarkable if we consider that when photography gained momentum, right after the phase of its pioneering dilettantes, such as Daguerre, Talbot, Bayard or our lost in the tropics, Hercule Florence (a French who migrated to Brazil), it immediately involved what was then the cream of the crop of science and technology. We can think of names such as Arago, Fresnel, Petzval, Fraunhofer, Herschel, Voigtländer and the entire network of academics, industrialists, military men and politicians who realized the importance of mechanically produced images. Well, while in Europe there was this contagious effervescence around the new invention and intense dispute over the primacy of its development, in Japan, people lived an agrarian life in a system that was still feudal, politically fragmented and obstinately closed to the rest of the world.

During a long period known as Edo, which lasted from 1603 to 1868, Japan lived under the Shogunate. In this regime, although there was an emperor, he had a figurative role and each Shogun held almost absolute power in his domains, notwithstanding the fact that he owed some obligations to the emperor, especially military support. There were between 250 and 300 of these shoguns called Daymio.

The Edo period was one of economic growth, social order, and the flourishing of the arts. The political leaders felt that they were doing very well as they were and did not need anything else. They adopted isolation as a premise, and foreign ships were not welcome in Japan.

Forced modernization

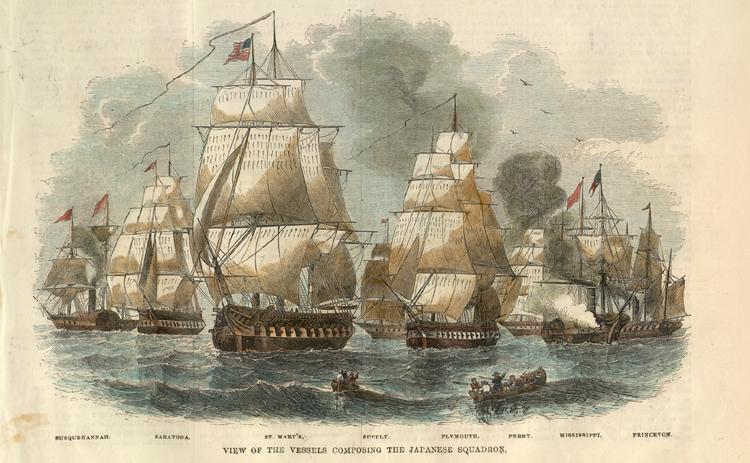

The interest of Western nations in having Japan as a market to explore grew to the point that the opening of its harbours was forced by a military expedition. In 1854, American Commodore Matthew C. Perry arrived in Japan with a fleet of powerful warships. But it was not for a traditional invasion. The objective was to establish a trade treaty that would open the Japanese market to receive products from the West and also to export their own. Japanese silk, for example, would be extremely profitable for Westerners.

The isolation of the Edo period brought many good things, but it also left Japan behind in important technological advances that were emerging from the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century in the West. This left the country militarily vulnerable and unable to resist. Forced to choose between war or a highly unfavorable trade treaty, the Japanese leadership chose the latter option and signed what became known as the Treaty of Kanagawa.

At the same time, there was a drastic change in the political system, known as the Meiji Restoration, which ended the Edo period and reestablished de facto power to the emperor. The country was once again able to implement comprehensive policies in all sectors of the economy and public policy, without resistance or disobedience from local leaders. The forced signing of the Treaty of Kanagawa exposed the inability of the shogunate, with its samurai, to represent and protect the country against foreign threats. This was taken advantage of by forces in favor of consolidation to restore central power.

But the Meiji turnaround went far beyond a rearrangement of political governance. There was, on the part of the new leadership, a conscious and deliberate desire to implement the Western modus operandi in several aspects of Japan’s life. It seems that the shock and, to a certain extent, the humiliation of the Treaty of Kanagawa convinced the Japanese that industrialization and the adoption of Enlightenment principles would be the shortest and surest path to making the country capable of establishing itself internationally and once again being the master of its own destiny in the competitive global scenario that was already looming. History has shown that they made the right choice.

But it was not without internal resistance. Many revolts by shogun leaders broke out and sometimes reached the proportions of a civil war. The Samurai class, which was essentially military men in the service of the shoguns, but with a strict code of ethics and highly respected by the general population, was simply abolished during the Meiji Restoration. Even wearing their typical haircut and hairstyle was prohibited. Many took up bureaucratic positions in the new order, but many participated in the armed revolts that followed. This was the case in the Boshin War, in which the shoguns’ army was defeated by the imperial forces. The photograph that opens this post shows samurai who took part in this war.

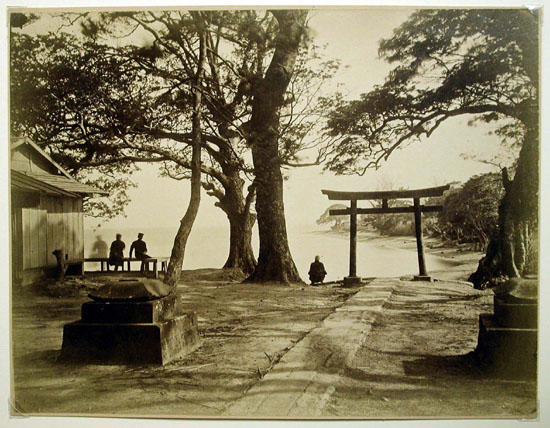

First contacts with photography

Photography, whose invention coincided with the turbulent end of the Edo period, made a late and very timid entrance into Japan. Despite the official isolation, some of the more powerful shoguns certainly had their eyes on what was happening in Europe. There was contact with Dutch merchants via a port in Nagasaki, and it was through there that the first photographic equipment arrived in the 1850s. Ueno Hikoma is considered the first Japanese photographer. He learned the wet plate process from the Swiss photographer Pierre Rossier, who was in Nagasaki in 1859/60.

It is also true that the American Commodore Matthew C. Perry, who forced the opening of the ports in the Treaty of Kanagawa, brought photographs and photographers with him on his 1854 expedition. He must have organized a parade of everything the Japanese were missing by not participating in the global market. Perhaps photography played a considerable role in seducing Japanese leaders. Judging by the fondness they would later develop for the medium, it is perhaps not too much of a speculation to imagine this possibility.

Nippon Kogaku K. K.

Nikon is one example among thousands of Japanese companies that were born and developed precisely in this spirit inaugurated during the Meiji Restoration. In Europe, we can say that the photography equipment industry emerged and grew organically. Companies gradually expanded their scope to incorporate new technology and take advantage of the new market. Sometimes with the help of academia or the government as a whole, as was the case with the award given to Daguerre, or the collaboration in the development of the Petzval lens, but in most cases, the great catalyst was the market dynamics itself.

In the case of Japan at the beginning of the 20th century, there was a sense of urgency for the development of a local optical industry and this growth needed to be induced. The Japanese government played a fundamental role in this. Nippon Kogaku, which would later become Nikon, simply means Japanese Optical Industry, and the K. K. simply says that it is a type of enterprise with shares in the market and limited liabilities of the shareholders. It was the result of mergers aimed at providing focus and scale to establish a national optical industry with size and cutting-edge technology. The Japanese government participated in the development of the strategy for these mergers and by 1917 the company was consolidated and operating. Government orders in the military area, such as binoculars and rangefinders, for example, guaranteed regular revenue while technologies were being developed, especially in the production of optical glass.

Nippon Kogaku continued the practice adopted in the previous century, at the beginning of the Meiji Restoration, of inviting foreign experts. Those came to work on specific company projects and in doing so also transferred knowledge to local engineers. These were temporary contracts, usually for two years. Eight German engineers were invited to work at Nippon Kogaku in 1921. They were experts in the design of lenses, microscopes and precision instruments. Nippon Kogaku, with the help of this group, designed its first photographic lens, called Anytar, which was based on the design of Zeiss’s Tessar.

The production of optical glass began in 1918 amidst several technical difficulties. In 1927 it was already capable of supplying large quantities with good quality. In 1932, the name Nikkor was adopted for the photographic lenses. The production of optical equipment was very diversified and largely served the military and scientific sectors. After World War II, Japan suffered many restrictions on the production of weapons and military equipment in general. The restrictions acted as an incentive for the company to focus more on the camera and photographic lens market.

In 1946, the Nikon name was adopted for the company’s cameras, and in 1948, the Nikon Model I was launched. It was a rangefinder, a camera with an optical viewfinder coupled with a rangefinder. Although it had several original solutions, it was also heavily inspired by the Contax from Zeiss Ikon of Germany, in terms of its external part, while the focal plane shutter and rangefinder were based on the Leica because they were simpler. The lens mount followed the Contax standard. Many design problems were pointed out when the camera was already on the market, and this forced the immediate launch of the Nikon M in 1949 and the Nikon S in 1950, addressing the necessary corrections. The most serious of these was that the format of the Model I was 24×32 mm, and the American market simply rejected this idea for 35mm film. The next model, the Nikon M, already incorporated the 24x36mm standard.

Until now, all the effort put into building the technical capacity necessary to provide the basis for a solid brand reputation still came up against the partially true but certainly perverse cliché that Nikon was just an inferior copy of the true gems of the European industry in terms of cameras and lenses.

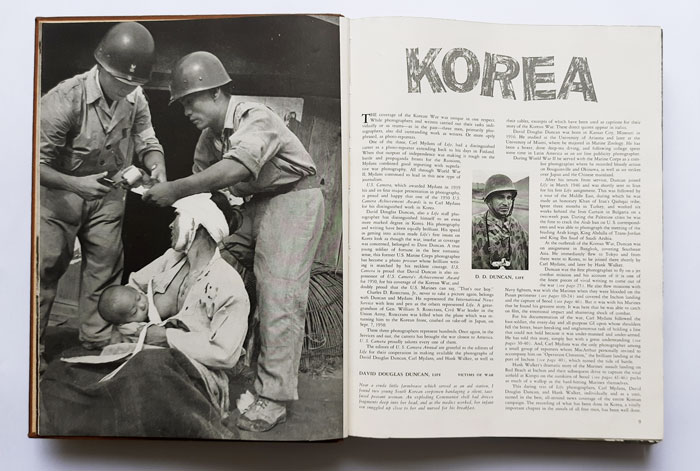

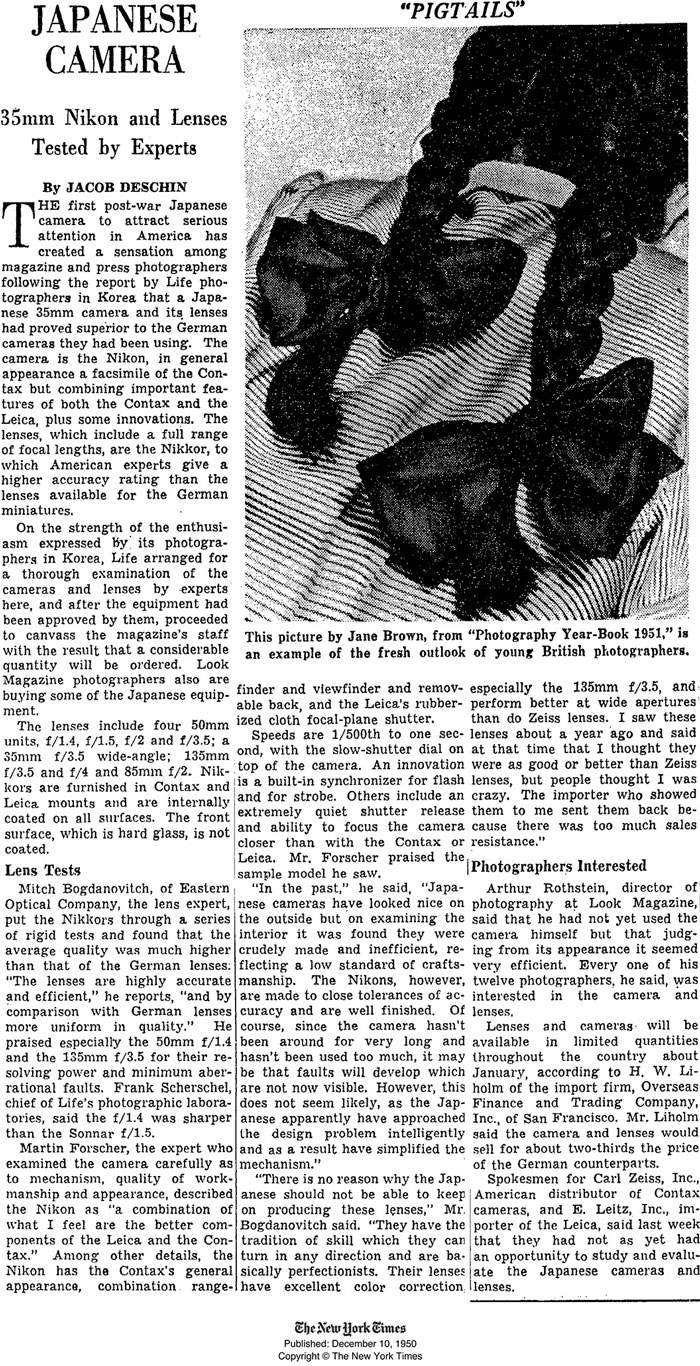

But this would change due to two factors. The story goes that the first turning point came with a report in the New York Times on December 10, 1950, in which the excellence of Nikon lenses was, for the first time, recognized and revealed to the world. The proof was reports in Life magazine to which photographers sent their photos of the Korean War.

The already renowned war photographer David Douglas Duncan went to Japan to report on the fine arts market. Once there, he had a local assistant, Mr. Jun Miki, who photographed him using a Nikkor lens. Impressed with the results, Duncan wanted to try out the optics and spent a week playing with a 35mm f/3.5. Confirming that it was not just a stroke of luck for the young assistant, he bought a complete set of Nikon lenses. A few days later, the Korean War broke out and he was sent there with his new acquisitions. It is said that, upon receiving the photos at Life, the photo editor asked Duncan why he was using a large format camera in a war, such was the definition of the images he had sent.

The news spread through the professional photography community and other envoys, such as Carl Mydans and Hank Walker, also stopped in Tokyo and bought Nikkor lenses. Walker also bought a Nikon S rangefinder camera. Arriving on the Korean peninsula, where temperatures dropped to -30ºC, he later reported that the Nikon S was the only camera, among Leicas and Contaxes, that continued to function normally.

All of this culminated in the article reproduced below, from the New York Times of December 10, 1950, in which it is stated, several times, that Nikkor lenses were better than their European counterparts. More than that, they would cost, in the local market, something like two-thirds of the equivalent from Zeiss or Leitz. It also mentions that Life magazine had already placed an order for a significant quantity and that Look magazine was following suit. It ends with the provocative comment that the Zeiss spokesman in the United States said that they had not yet had the opportunity to evaluate the Japanese cameras and lenses.

Without discrediting the facts, I believe that there is a lot of subjectivity embedded in this story. I believe that there was a great desire to demean everything that was German because of the war and Nazism. The Japanese were also enemies, but they capitulated and perhaps the events of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, together with the formal surrender of Emperor Hirohito, gave the outcome a clearer perception of the superiority of the victors over the vanquished. This pleasure Hitler managed to steal from the allies with his disappearance. It was as if the bill for the atrocities in the concentration camps remained unpaid, this fueled a certain animosity towards the Germans and it took a while to dissipate.

So I think it is understandable that there was a favorable climate for finding substitutes for German products, and Nikkor lenses were of sufficient quality to allow other factors to act as the deciding factor. It does not seem reasonable to me to think that a Zeiss Planar or Sonnar lens could be clearly worse than another similar lens developed with equivalent technologies and materials, as was the case. But, in any case, the whole story of the Korean War photographers and the subsequent article in the New York Times gave a huge and deserved boost to Nikon’s production, which was undoubtedly already among the best manufactured at the time.

The second turning point came when they decided to transform the Nikon rangefinder into a Single Lens Reflex camera, giving it a mirror and a prism. Thus was born the Nikon F. Single lens reflex cameras had existed for a long time. They started out in large format and were scaled down until Ihagee, from Dresden, launched the Kine Exacta for 35mm film. The Kine Exacta had all the ingredients to dominate the market, as the Japanese did in the 1960s: focal plane shutter, bayonet mount, a wide range of interchangeable lenses, prisms and focusing screens, and was highly reliable. However, Ihagee was not very lucky at the end of World War II, as it ended up in the communist side, in East Germany. After a respectable success in the 1950s, it was incorporated by Pentacon and that was its demise. Meanwhile, big names like Zeiss Ikon and Voigtlander insisted on keeping the leaf shutter, which complicated the construction and price of cameras and lenses. Leitz continued with its flagship and in the 1950s launched the Leica M, successor to the classic Oscar Barnack design, excellent, but it was again a rangefinder camera, a concept that… ok, has its fervent community, but it was unable to prevent the massive migration to other shores.

At that time, the Japanese industry came in with quality, a lower price and the combination that would be the favorite of photographers in the following decades: single-lens reflex, focal plane shutter and bayonet mount for a multitude of interchangeable lenses.

The Nikon F concept

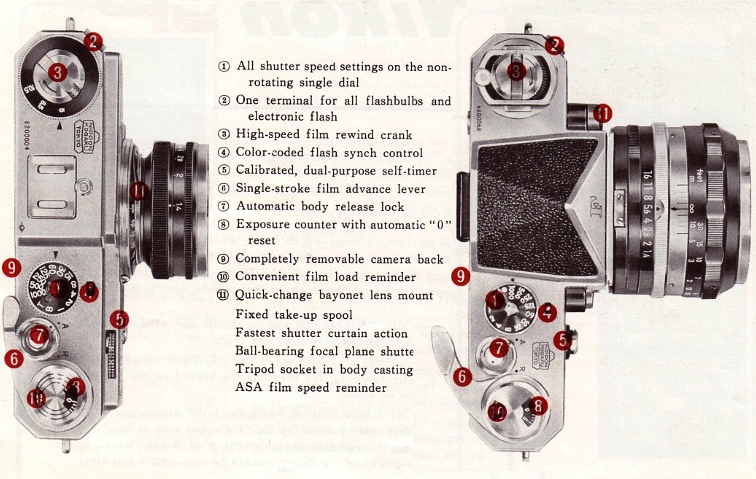

The image above is from a Nikon brochure and was adapted from the excellent Richard Stoutz’s website. This was the decisive move that put Nikon on the path to rapid leadership in the new era of photography, dominated by Single Lens Reflex cameras using 35mm film. They took the proven design of the Nikon SP rangefinder (left) and adapted a mirror and prism to it, thus dispensing with the rangefinder.

They created the now legendary Nikon F. Also extremely fortunate was the mounting of the lens with a bayonet that remains the same practically to this day. Of course, the “conversation” between lens and body depends on their own features: with or without a light meter, with or without automatic apertures, with or without autofocus, but the bayonet itself was a standard that was created and no longer needed to be changed.

Not only Nippon Kogaku (founded in 1917), but also Pentax (1919), Olympus (1919), Minolta (1928) and Canon (1933), among others, finally gave Japanese industry a status of great international respect in the manufacture of optics and cameras. They showed excellence, not only in technology but also in cost and efficiency management and in understanding the needs and fancy desires of both professional and amateur market.

German companies undoubtedly had a very high level of technical expertise, but the leaders in particular did not seem to care much about the final price of their products. Companies such as Zeiss Ikon and Voigtlander had extensive portfolios, covering practically all types of cameras. This must have been a source of pride for the engineers who displayed great inventiveness by creating entire, autonomous systems of cameras, lenses and many, many accessories. However, this increased the costs of inventory of parts, production and after-sales. We can say that the absolute leadership they had until then made them believe they could shape the market according to their conveniences. The classic example of this was the aforementioned insistence on leaf shutters instead of focal plane shutters for SLRs. This topic is discussed in more depth on the Contaflex website.

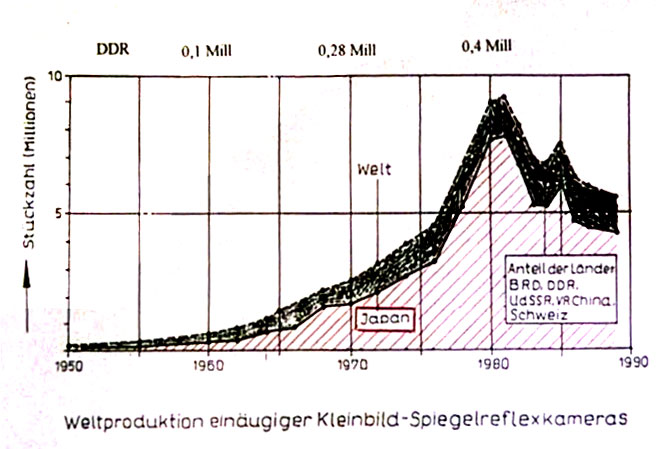

The result of all this can be seen in the graph below. In it we can see in units (millions) the global sales of SLRs. We see Japan (hatched in red) vs. the rest of the world (in black). It was taken from the video Exakta – The Rise and Fall Of a Legendary Camera – A film by Günter Eiselt, which can be found at this link.

The Nikon F was launched in 1959 and remained in production until 1973. It was instrumental in redefining the “made in Japan” label that had long been synonymous with cheap, low-quality products. It was during the Nikon F’s time that SLR cameras took press photography into new territory, and it was the ultimate representative of the category.

The Leica Barnack, whose iconic photographer was Cartier Bresson, defined discreet photography, the image stolen at the “decisive moment”, with a small and silent camera. With the Leica, it was as if the photographer were hidden in the scene, as if he was transparent and the camera, in fact, seemed to disappear in his hands. The Nikon F represents, as an SLR, a new, a more assertive and noisy photographer. Its weight, robustness, design, size and mode of operation were more in line with the photographic act that was established in the 1960s, in photojournalism, as social documentary photography, photography that was critical of society and aimed to reveal hidden truths and injustice. The pages of magazines began to show more and more conflicts and tragedies of all kinds.

This is a Sonnar 50mm, for Contax. It is a lens from the 1950s. Its design is slim, sober and elegant. It seems that the idea was to reduce the presence of the lens as much as possible.

This is a 50mm Nikkor lens fitted to a Nikon F. It has an imposing design that is anything but discreet. In socially engaged photography, a camera resembles a weapon makes a goo match. The lens body, instead of the minimalism of the Sonnar, seems to want to grow and gain muscle. The focus ring, black and thick, is reminiscent of the barrel of a gun. This was an instrument more in line with the photography of the counterculture, the Cold War, student movements, the alternative press and engaged photography as a whole. Wearing a Nikon F hanging around your neck was already a statement in itself.

Comparing again with Leicas and Contaxes. Focusing on a rangefinder is a more technical and objective operation. The image is there and the photographer matches a small piece of the accessory image, brought by the rangefinder, with the real one, which is always the same, regardless of the photographer. On SLRs, the focus ring brings the image from the indiscernible to the sharpness of reality, the photographer feels more like the creator of that image. He is the one who seeks it and gives it meaning.

Focusing looking through the viewfinder of a SLR, has become the iconic gesture of photographic creation. Above is Clint Eastwood (lead role and director) with Meryl Streep, in The Bridges of Madison County (1995). He plays a National Geographic photographer. The camera? Nikon F.

Upon its launch, the Nikon F became the ultimate symbol of the SLR almost instantly. It helped to shape a new image of photography and made photographers, more glamorous, full of dynamism, plenty of youth and more adventurers than ever before. It found its ultimate expression in photojournalism. The invasion of SLR cameras brought a combination of technique, art and activism to the photography profession. The Nikon F was the spearhead of this new role.

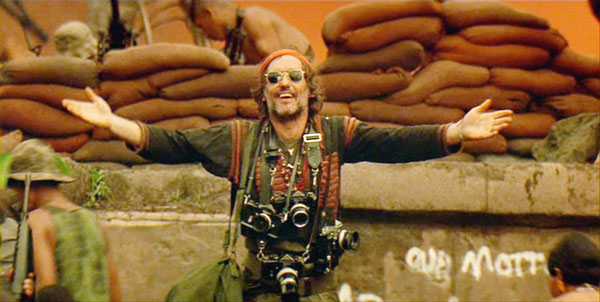

Many movies from the 1960s and 1970s, about war, romance and existentialism, found a perfect fit by showing a photographer carrying a Nikon F, or perhaps a bunch of them. Above we have Apocalypse Now (1979), by Francis Ford Coppola, an epic delving into the barbarity of the Vietnam War (1955-1975). The Nikon F was the camera of the Vietnam War par excellence (leaving the second and honorable position to the Leica M). Its robustness and design go so well with weapons, radios, jeeps and uniforms that in these situations it almost seems to have been designed for combat.

The Camera

Cameras have something in common with clothes: it’s not enough to just look at them, you have to “wear them”. Having a Nikon F in your hands, just knowing its history and what it meant to photography, is quite an experience. It has the right weight to convey robustness without losing mobility. Everything that moves, turns or slides, does so smoothly and firmly. It owes nothing to the Germanic standard of fine mechanics.

It is perhaps best known in the version with a light meter, as in the advertisement below. The Nikon F and its successors F2, F3, FM… were designed within a “system” concept in which many of its parts can be replaced and many accessories attached. The only permanent part of the camera is its body with shutter and film transport. The lenses can be changed, a light meter can be added, several prisms and focusing screens can be added, there is also a waist level viewfinder, a motor-drive can be attached, a magazine for meter-long film rolls, a flash shoe and bellows for macro, in addition to the usual basics such as filters, trigger cables, lens hoods, eyepieces to correct diopters, etc.

The Nikon F in the collection uses a prism without a light meter. I prefer it this way because of its reduced size (compared, for instance, to the Photomic T, above) and also because nowadays it is very difficult to find one that still works. The ad draws attention precisely to this modularity and also to the automatic mirror that returns to its position after the shot is taken. This is commonplace nowadays but it wasn’t back then. The diaphragm is also automatic, which remains open for focusing and light metering, only closing at the moment of exposure and then opening again.

In the controls section, the speeds follow the standard for SLR cameras of the time: B, T and 1 to 1/1000 s. All speeds are adjusted on a single dial on the top of the camera. Also on the top is the exposure counter, which automatically returns to zero when the back is opened is inserted, and the rewind lever. A hot shoe for a synchronized flash can be installed on it.

One point that the Nikon F carried over from the Nikon rangefinders and that is a cause for widespread complaints is the position of the shutter button. It is too far back, outside the natural position where our index finger falls. This was corrected in the Nikon F2.

Another point that is not very pleasing is the rear cover, without a hinge, which needs to be removed completely. Again, something that came from rangefinders and was the standard even on Contaxes and Leicas. The key to open or close the rear cover is on the base of the camera and there is also a memorizer of the ISO of the film that was loaded, at that time ASA, but numerically the two scales are identical.

If you are looking for more details about models, features, accessories and information about the long, fruitful and exquisite production of Nikon F, visit the page: Nikon F Collection & Typology by Richard de Stoutz. It’s fantastic. For example, according to information published on this site, my Nikon F, which appears in this post, with serial number 6883627, was produced between February and April 1968. There you can also find everything about lenses and accessories.

I usually end my collection posts with some photos taken with the equipment. But since I still have two Nikon F2s and one FM, and since lens portability is a fantastic thing in the Nikon system, I can’t say for sure which camera I used to take each photo. So I’ll put some in the F2 and FM posts, saying which lenses they were taken with.

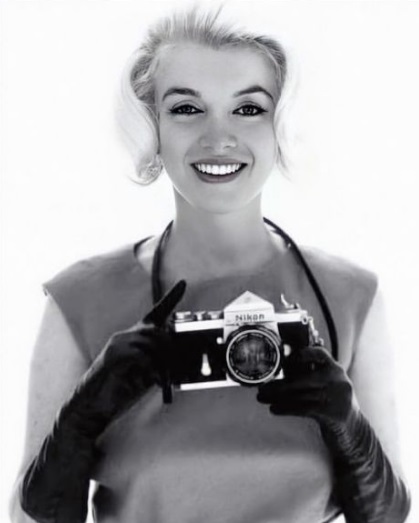

So, as not to finish without at least one photo, even if it’s not mine, I will leave you with one image and two stars.

This is a very interesting article about the Nikon F camera!