Penti II | Pentacon

The first truly photographic lens, thought and calculated for photography, was by a mathematician, Joseph Petzval. Photographic equipment manufacturers were mostly scientific equipment manufacturers. This was not just in the early days of photography. Ernst Leitz was a respected microscope firm and his famous Leica, launched in 1924, had been designed by engineer Oskar Barnack. I am remembering this fact, this heritage, this DNA, to ponder how unlikely cameras and lenses would be conceived from an aesthetic motivation or concept. They would hardly have a “style” away from the lab environment or the machines in factories.

It is true that at the turn of the twentieth century we can spot some experimentation, for example the colorful Brownie # 2 from Kodak. But a much bolder emancipation from the “instrument” towards the “object” came only much later. It was a post-war cultural shift that took the automotive, furniture, appliances, clothing, all design trendsetters sectors, and added a new category to photographic equipment as well.

“The elaborate households of the prewar years were gone, replaced by informality and adaptability. Gone, too, was the conventional approach to furnishings as expensive and permanent status objects. New materials and technologies, many of which had been developed during wartime, helped to free design from tradition, allowing for increasingly abstract and sculptural aesthetics as well as lower prices for mass-produced objects”. Goss, Jared. “Design, 1950–75.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000.

That’s how an avalanche of plastic, bakelite, and pressed plate cameras came in, with many colors and shapes that went so well with a Cadillac or a bottle of Coke. They were aimed at the amateur market and lacked the ambition, as Jared Goss’s text, quoted above, pointed out, of permanence. New models were launched in profusion and it seems that the idea was that the photographer would renew his camera along with his wardrobe and following the fashion.

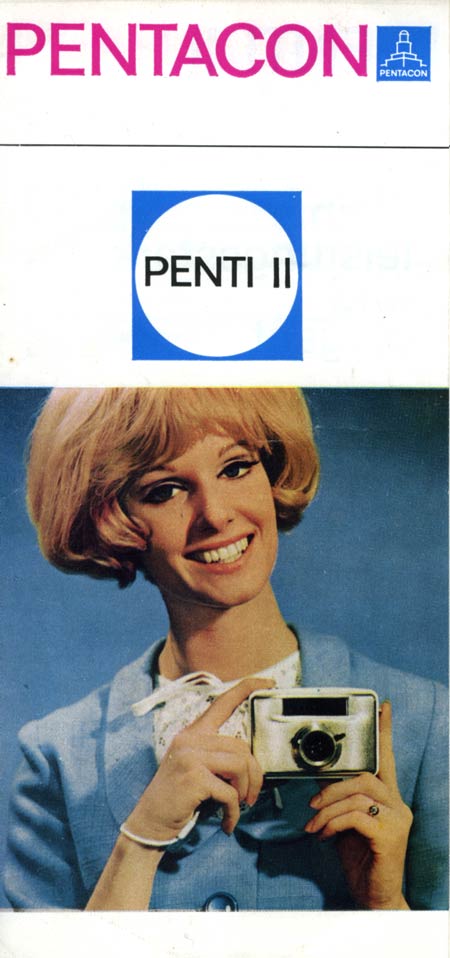

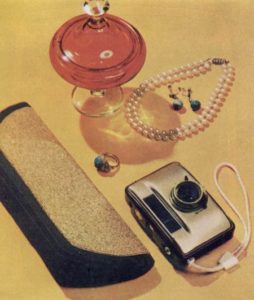

The image that opens this post is from a Pentacon brochure featuring Penti II. The model, except for the smile, could be a spy for Agent 007’s movies. This was a camera for the female consumer in a market that was overwhelmingly male. The next photo of the same leaflet shows what the charming character would bring when leaving home. In addition to the accessories: necklace, earrings and ring, a Penti II was the finishing touch to her lifestyle.

But the difference between Penti and most of other distinctive-design cameras that appeared in the 1950s and 1960s, is that it features a complete set of manual adjustments.

- speeds B, 1/30, 1/60, 1/125

- diaphragm f/3,5 – 22

- focusing ring from one meter to infinity

In addition, the Penti II has a built-in lightmeter and a speed-priority auto mode.

The lens is a Meyer Optik Domiplan multi-coated or a Trioplan with 30mm focal length.

Pentis are 18 x 24mm, half frame, cameras on 35mm film. This implies that “portrait” mode is what you get with the camera in the horizontal position. There is a photo counter that needs to be manually reset when loading the film. Penti’s particular is the advance mode. The horizontal rod protruding on the left of the camera should be pushed inward. With this movement a tip moves through the slot just above the frame, visible in the picture below, and pushes the film into a second cassette.

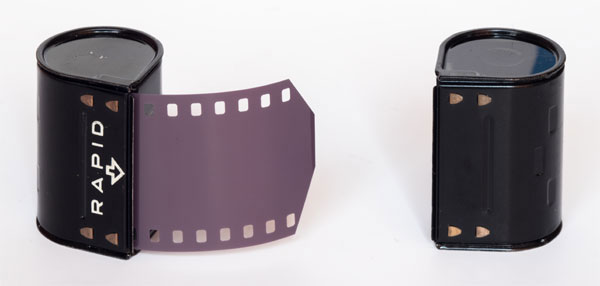

Penti uses a special type of 35mm film cassette. It is a system identical and interchangeable with the one introduced by Agfa, called Rapid, but it was restricted to some amateurs cameras of that time. Known as SL System, where SL comes from Schnell Lade in German, or Speed Loading in English. Cassettes do not have an axis on which the film is wound. Today, as there are no more such films for sale, you need to cut a strip, enough for 24 half-frame photos, and push it into a cassette in total darkness.

There is a spring loaded plate that holds the film flat and on the track and guides it into the second cassette as it is pushed by the camera’s advance system. When you close the camera, the back cover compresses the spring, which is inside this kind of “button”, and so presses the film.

The Penti were designed by Walter Henning in the late 1950s while working at VEB Zeiss Ikon, which was Zeiss Ikon in post-war East Germany. But the production went to Welta and the original name was Welta Orix, produced in 1958 only. Soon after it changed to Penti and was manufactured by Pentacon with the design ready to receive the photometer in the Penti II model. About 800,000 cameras were produced from 1959 to 1977 (source: Camera-Wiki)

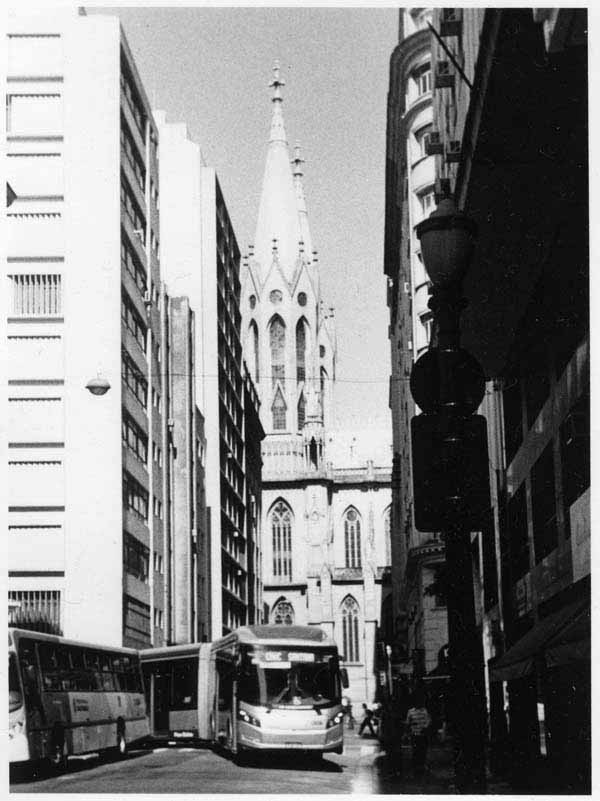

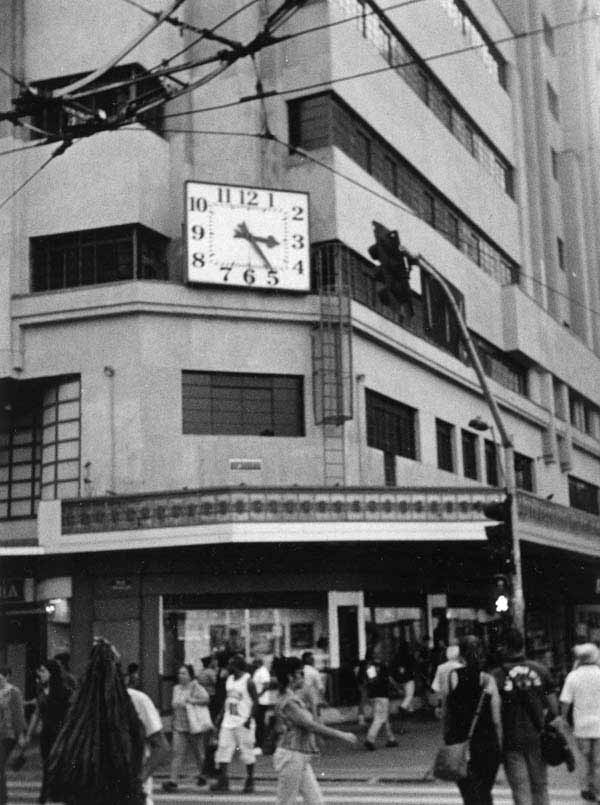

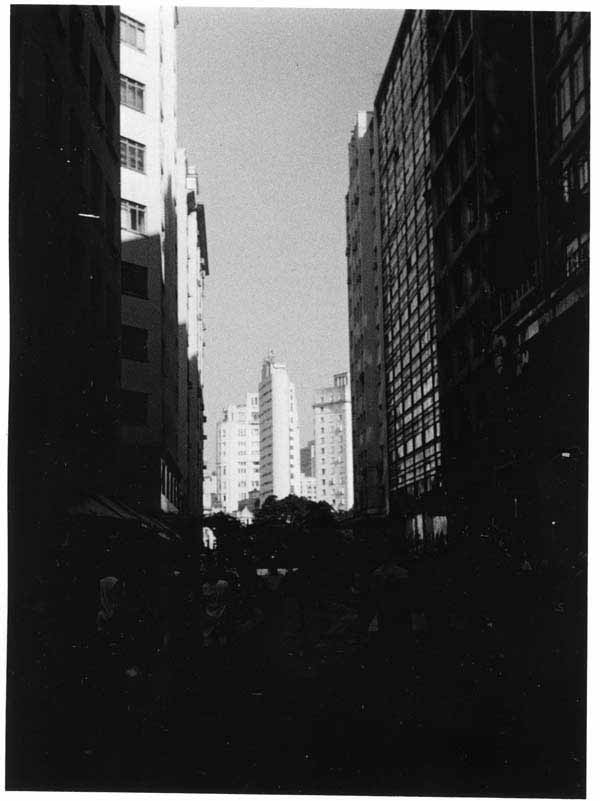

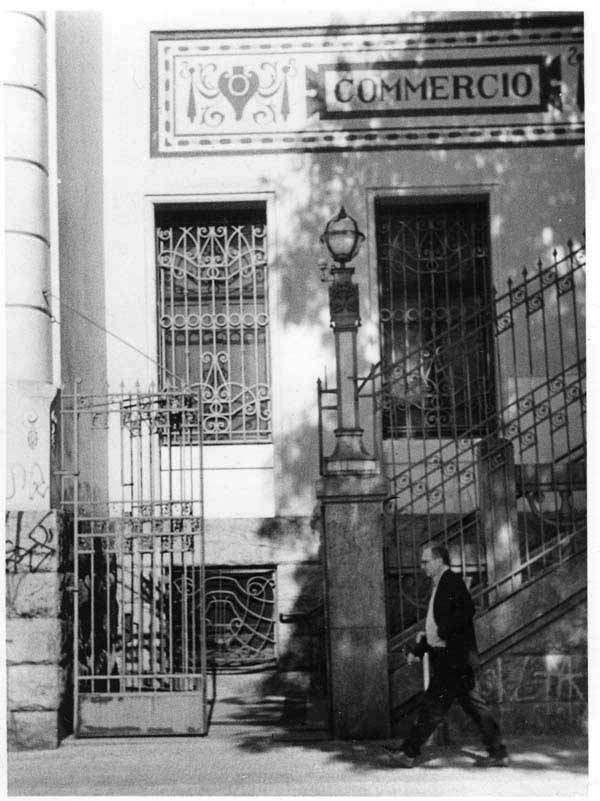

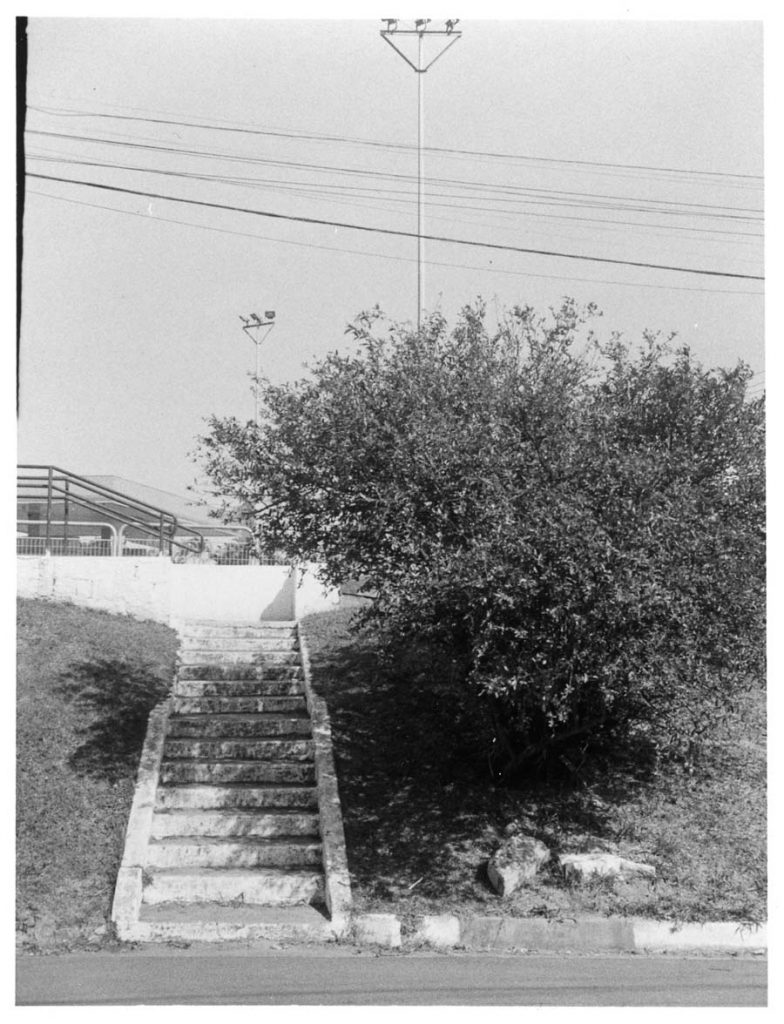

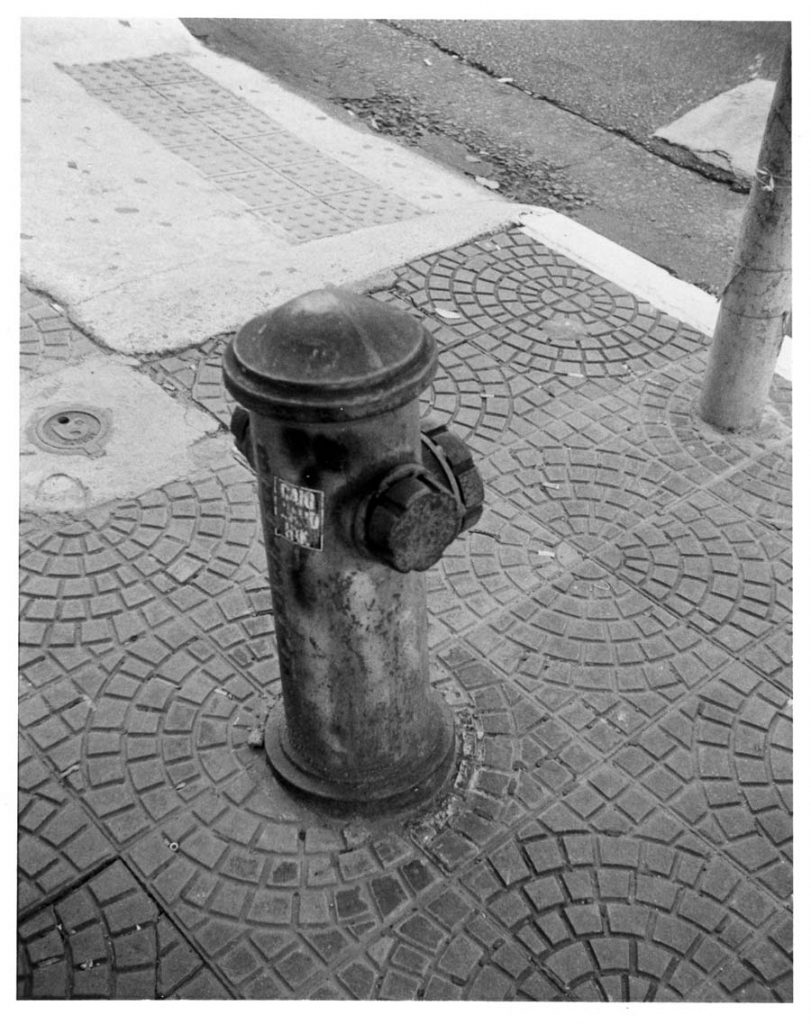

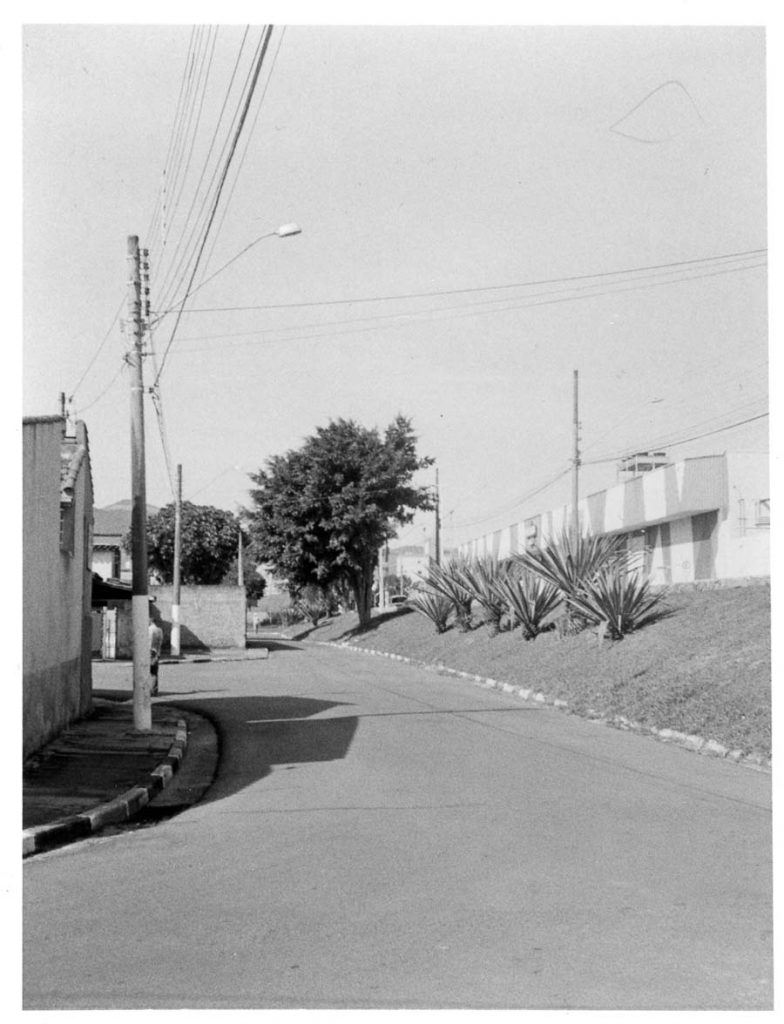

Like all basic viewfinder cameras and manual controls, the Penti II induces us to simplify photography and makes us use the camera simply to record what we’re seeing. In this sense, its design so full of charm and nostalgia turns out to be a very nice complement to a tour or event without any major photographic pretensions. The half frame limits the magnifications putting film grain more in evidence. Unless this is also an interesting and desirable aesthetic element, it is necessary to consider a film/developer combination suitable for a finer grain.

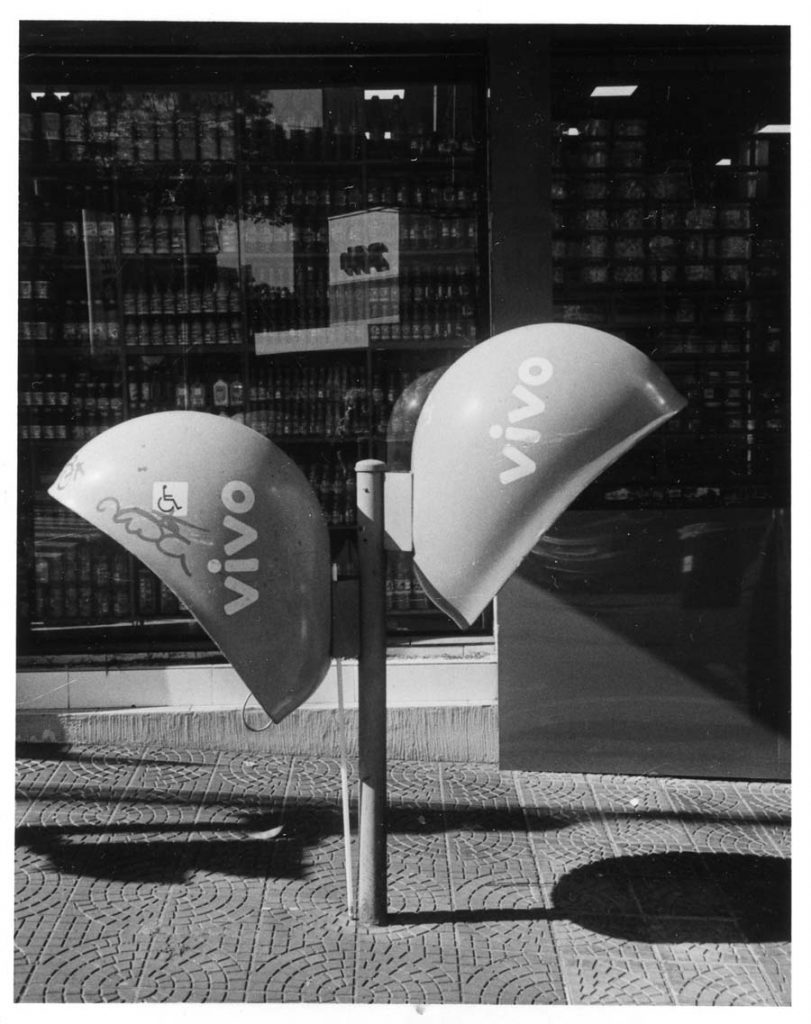

This gallery show pictures from one film shot while walking in Sao Paulo downtown. Those are prints 15 x 20 cm (6 x 8″) in Ilford fiber. Film was Ilford FP4 developed in homemade Parodinal 1:50. It came out so grainy and my scanning seems to have enhanced even more this feature. I need to try out another developer. Even better, with this camera, would be a color film – next time.