Robot II | Hans Berning

This camera was designed in 1930 by Heinz Kilfitt (1898-1980), who at first followed the career of his father, a watchmaker, but soon became interested in optics and photography. He presented the Robot project to Agfa and Kodak, but neither was interested. The design was then sold to Hans Berning who started a new business in 1934, bearing his own name, for the production of the new camera. Two models were released the following year, Robot I and II. The company exists to this day but the Robot camera was discontinued in 1959.

Many particularities built into this small camera. The most important, the one that is certainly top of mind, is the fact that the film advance and shutter cocking is made by automatically after each shot by a spring mechanism and this allows to shoot up to 4 photos per second. The shutter button needs to be pressed each time. It is said that a photographer well acquainted with the camera can reach up to 5 photos per second if he synchronises his movement well with mechanism’s pace.

Recalling that the 135 film, the pre-loaded cartridges, was launched by Kodak along with its Retina camera in the year 1934, manufacturers using 35mm film, such as Leitz, for example, who introduced the Leica commercially in 1924 , needed to propose their own solutions to use the film that was always sold only “in bulk”. For Robot, Kilfitt chose to make 24 x 24 mm frames. Something between the 18 x 24 cinema format and the Leica 24 x 36 format. This allowed for something like 50 shots per film load. When using the camera, the square format always brings the comfort of being able to hold the it always up-right as there is no need to rotate it more than 45% to obtain any possible composition.

It uses two film cartridges called K-cassettes. The film is loaded on the first and as the photos are taken, it is spooled into the second. There is a special reason for this. Due to the automatic advance mechanism the two cassettes have been designed so that when pressing the camera back, in order to lock it, the slits through which the film passes open and allow it to slide freely without offering any significant mechanical resistance to the movement.

It is very important when buying a Robot I or II to verify that the cassettes are there, because without them the use of the camera is impossible. A normal cartridge 135 does not fit into this camera. The second cassette also brings the peculiarity of not having to rewind the film. The camera is always ready to be opened and the film removed, and can be returned to be finished later. Only in 1951, with the success of the 135 format, a the Robot IIa was released accepting the standard 35mm film cartridges.

The size of the camera is something that catches the eye. It is very compact measuring 106 x 62 x 31 mm (4¼ x 2½ x 1¼ inches) but weighs like a 35mm mono reflex. Its all-metal construction makes it very sturdy and stable. The small format made possible to dispense with a rangefinder without affecting the sharpness of the images as focusing by guessing the distances is very effective. Another interesting feature is that the focus ring has “clicks” at some preset distances. With this feature it is possible in the dark, or even with camera inside the pocket of a jacket, pre-adjust the distance if you memorize the sequence and count the clicks.

These features all added up to make it a camera much appreciated by the German army. It is also associated with the idea of espionage and brings a 90º viewfinder that helps in concealing the act of shooting pictures. Just turn the small lever on the top of the camera and a mirror sends the image, that enters the front viewfinder, to a second eyepiece positioned on the side of the camera. The fact that it could be fired several times only by acting on the trigger, perhaps with a cable, made it the ideal camera to be hidden in a suitcase or other object unsuspected to take photographs. There was also a specially developed model for the German Air Force, the Luftwaffen Eigentum Robot, which had an extra spring allowing a larger number of photographs without rewinding. Finally, there was a factory retrofit with the option to make an adaptation to minimize the noise of the film advance and allow indiscreet photos even in indoors.

Many lenses were produced by Zeiss and Schneider to equip the Robots. For Robot II the normal lens was 40 mm but also wide angles of 26 and 30mm were part of the line. In the long focus was used basically the focal 75 mm. Among normal lenses, the standard was Zeiss Tessar 40 mm f / 2.8. Another, more rare, the Biotar 40 mm f / 2.

In current use, for those who are accustomed to the standard of the lenses with antireflection treatment, the contrast of these lenses may be lacking and they will have a more dated signature, typical of the period before the Second War. Notwithstanding this feature which tends to produce a more compressed grayscale, the optical quality of the image in terms of definition is excellent for all the optics employed in the Robot.

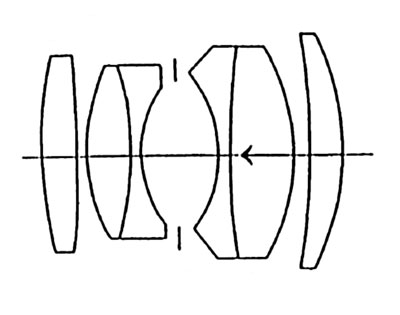

The Biotar was designed by Merté of Zeiss in the early 1930’s. It is a Double Gauss derivative, a concept used, for instance, in the famous Planar designed by Paul Rudolph in the late 19th century. Most modern lenses with apertures f/2 or more belong to this Double Gauss lineage, with the difference that they are usually asymmetrical while Double Gauss was initially drawn as a pair of symmetrical doublets around the diaphragm. Biotar design was developed to the astonishing point of offering an opening of f/1.4 in one of its movie versions.

Above the schematic drawing of Biotar created by Merté (source Vademecum). It is easy to understand how such a design would later benefit from coating treatment. There are 8 air/glass or glass/air passages plus two glass/glass. In all of them there is always a bit of light that spreads and eventually reaches the film uncontrollably creating a fog effect and reducing contrast. It is very important to use a lens shade in such cases. However, the viewfinder is so close to the lens that it is almost certain that the a lens hood will hide part of the scene being composed.

Speeds are set at a button on the front of the camera, it has B and goes from ½ to 1/500 s. Synchronises flash at all speeds through a connector just above and next to the speed setting. The shutter takes advantage of the small frame, 24×24 mm and is of the rotary type, a simple and efficient mechanism. There is a progressive frame counter at the top of the camera that needs to be adjusted every time two new cartridges are installed.

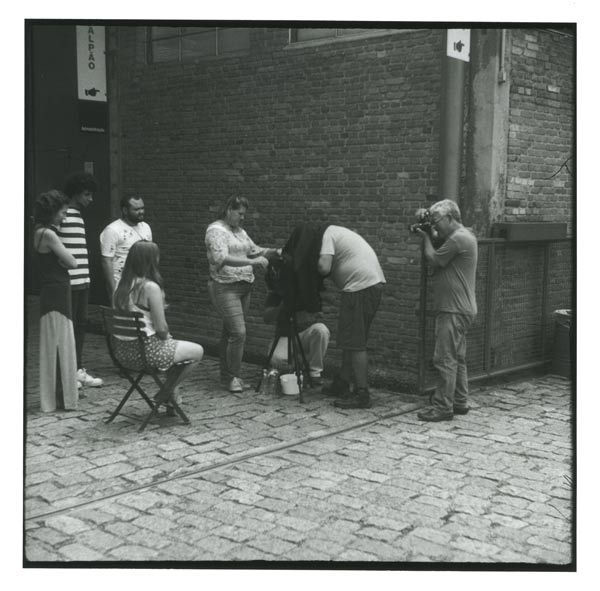

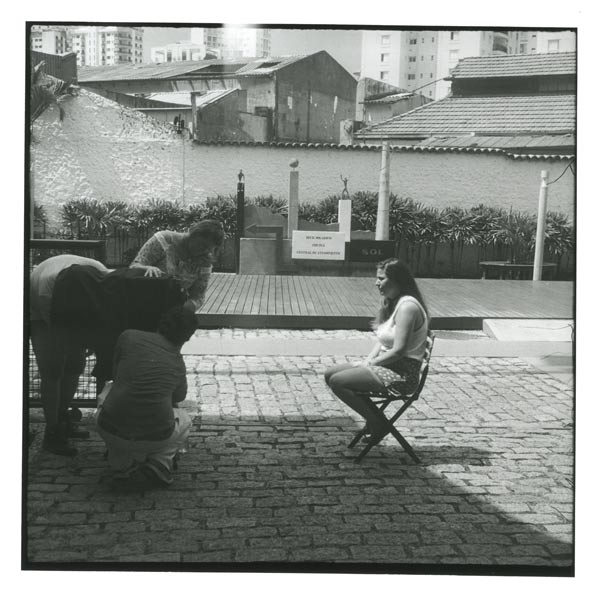

Some photos made with this Robot. Film T-MAX 100 revealed in Parodinal. These are faithful scans of enlargements carried out on Ilford glossy fiber paper.

This photo presents problems of light leakage due to careless handling of the Cartridges. As they have the spring that allows them to open when inside the camera, they need to be handled carefully so this does not happen outside of it. Luckily, I think the final result was still interesting.

Above and below a typical more compressed grayscale that one gets with this type of lens when the subject is illuminated diffusely by a cloudy sky, for example.

In cases of very contrasted scene, the reduction of contrast in the lens, ends up having a beneficial counter effect by balancing the grayscale more and rendering the textures better.

How do you set the ASA on the Robot2?

Hello William, the Robot camera I have has no lightmeter, so there is no ASA or ISO setting. Not even for a memo of the film loaded as some cameras offer.

My mother, who worked at the Pentagon, was given a Robot during WWII, by a OSS officer who had just come back from serving in Germany, undercover as a German citizen. She said it had a very heavy large Carl Zeiss lens that was f1.2, possibly a prototype, I know what you are thinking it was a f2, but it was confirmed by a photographer friend that it was a 1.2. I have seen pictures taken by it, and the contrast, contour rendering, and bokeh is very similar to my 1949, 75mm f1.5 Biotar. I wonder if you have ever heard of such a lens. Unfortunately, it was given away before I was born.

Hello, thanks for your visit, I checked the only literature I have, a Focal Press book only about the Robot system and it does not mention such lens. If it was a prototype you will hardly find any official or regular information about it, like in manuals or advertising. If at least you knew the lens’ construction type, then it would be possible to check its variations. Sorry for not being able to help you.