This is a truly iconic camera of an era. It was launched in 1967, manufactured until 1984 and sold 10 million copies. According to Camera-wiki, this count includes the more recent versions with a plastic body. But even so, the original metal version, pictured above, passed the 5 million units mark.

The reason for this success really lies in the project itself. In photography, the principle that every time you win on one side, you lose on the other, is very present. In this way, each camera, seen as a combination of many optical parameters, exposure settings, features, etc. follows the basic rule that many features exponentially increase the final price and make the operation significantly more complex. At this extreme, most of potential buyers are out. They are not that implicated to the point of expending hours of study just to snap some weekend pictures . On the other hand, very simple cameras tend to offer a restricted field of application, producing satisfactory images only in very limited cases. The Olympus Trip 35 is an extremely happy combination of parameters that delivers what most people want with the minimum of effort. It optimizes versatility while keeping its operation extremely simple.

It produces a negative in the classic 36x24mm format on 35mm film. At this point, although aesthetically similar, it is very different from another success from Olympus, the Olympus Pen, a 24x18mm half-frame camera.

It is a camera to be used in automatic mode. It has a selenium light meter, without battery, which is located around the lens. Its photo cells are positioned in such a way that the addition of a filter provides an automatically corrected reading as the filter covers the lens and photometer at the same time. Based on the scene’s brightness reading, the Olympus Trip 35 chooses between just two speeds: 1/40 or 1/200s, and apertures ranging from f/2.8 to f/22.

With these possibilities, photographs from well-lit interiors to sunny landscapes are viable using ISO100 film. At ISO400, with normal development, even scenes with weaker lights can still produce good negatives.

Manual mode is also possible by specifying any aperture. In this mode the speed is always 1/40s.

The lens is not interchangeable. Its focal length is 40mm, which makes it a little more angular than a normal lens, which would be 50mm for this format. It’s great for groups in tighter spaces, landscapes and indiscreet street photography, without even using the viewfinder. The size of the negative gives freedom for some subsequent crops to adjust composition. As for the optics, it has 4 elements in 3 groups and follows the concept of the famous Tessar, a simple lens but famous for being extremely sharp for its type of construction.

You cannot expect wonderful performance from this lens. At 1/40s, without a tripod, you have to admit some camera shake. Zone focusing is not as precise as on a rangefinder or reflex camera and we must not forget that it is an amateur camera. For modest enlargements it works well most of the time and on several occasions it even surprises positively. I took the photo above thinking it would give much more flare, but it was possible to obtain an image that I consider very pleasant, with a level of flare that does not compromise and even produces an atmosphere consistent with the image.

The focus is the point where Olympus broke with the obvious and was very happy in doing so. Not being a reflex camera and not having a rangefinder, the natural thing would be, as has always been done, to put a distance scale in meters and/or feet.

But instead, considering that most amateur photographers probably don’t feel confident estimating these distances, a scale with only 4 positions presents the question very cleverly: do you want to photograph a bust? Someone with half body? A group? A landscape? The four icons are self-explanatory and intuitively resolve the focus issue. They correspond to 1.0, 1.5, 3.0 meters and infinity. With a maximum aperture of f/2.8, the depth of field ends up providing satisfactory sharpness in the overwhelming majority of photos using this standard.

The viewfinder has a bright frame to indicate framing. Considering that the lens takes the photo from a different position in the viewfinder, in cases where the subject is very close it is necessary to consider this difference.

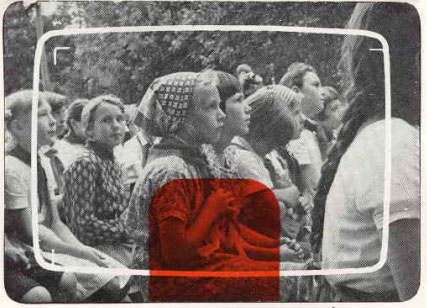

To do this, the display shows marks that position the frame a little lower and a little to the right. These marks should be considered in these situations. See above for a photo of the Olympus Trip 35 manual.

That red area on the display is not part of the graphic design of the 60s manual. It is actually a safety device to avoid under-exposure of the photo. Every time the film’s ISO requires an aperture greater than f/2.8 and a speed slower than 1/40s, a mechanical red tab rises in the viewfinder and the camera does not fire. If the photographer still wants to take the shot, he has the option of using the aperture he wants by going to manual mode.

In cases of a well-lit object against a dark background, when the safety lock may be activated because it appears to be an underexposure case, it is possible to “trick” the photometer by changing the indicated ISO to a higher value. The photo can then be released and, with a little luck, the subject will be well exposed.

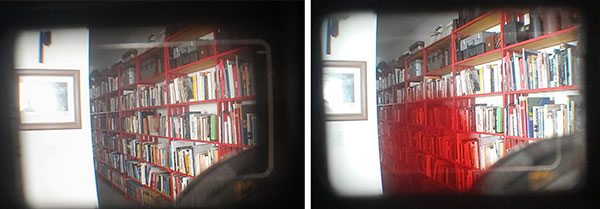

This is what the viewfinder looks like, photographed with a cell phone. Note that the lens tube appears in the lower right corner. This is a common problem with viewfinder cameras as the viewfinder is very close to the lens. But Olympus knew how to take advantage of this and placed the distance scale in a position that is visible and you can check it one last time before clicking.

The film is not advanced by lever, as in most other cameras. It’s a roller on the back of the camera to the right of the viewfinder. The frame counter is on the top of the camera, as well as its serial number. The Olympus Trip offers a hot shoe for flash sync in M or X modes. But it also has a standard flash connector on the front panel. To the left of the shoe is the rewinder to wind the film back into its drum when the last photo is taken.

It’s a lot of fun to use a flash bulb with the Olympus Trip 35. There is an Olympus Pen Flash the size of a matchbox that accepts AG-3N flash bulbs. The battery is more difficult to find as it is a 15V battery, only very specialized stores still distribute this size. But it is possible to adapt the very common 12V type A23 batteries, which are smaller. If the capacitor is no longer working, it will also need to be replaced. But it’s not difficult to do this.

Here is an example without and with flash bulbs to fill in the shadows a little but without making the light too artificial.

In this case below I also used an AG-3N flash bulb with manual mode at f/22.

The idea was to compensate for the backlight from the street and I thought it worked well. Without the flash, faces would have a very strong shadow, or part of the street would be overexposed.

At the base of the camera is the lock to release the film so it can be rewound and a standard 1/4″ tripod socket. The filter thread is 43.5mm

The ideal, what normally makes camera and photographer happy, seems to be photos with good lighting and objects located 3 to 5 meters away. This photo of the bike is sharp, contrast and details in the shadows and highlights within a good balance. The film was an Agfa APX100.

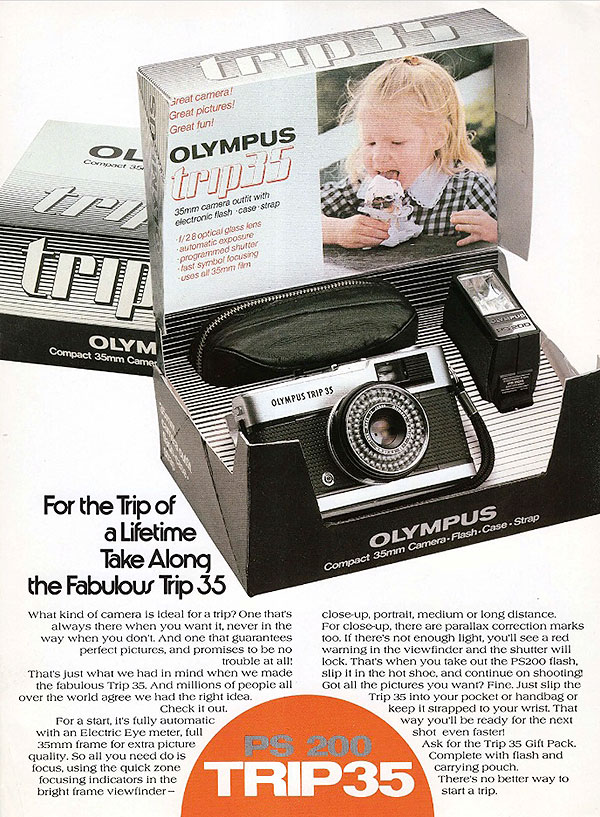

With so much success, the Olympus Trip 35 had a strong presence in advertising. Below is a magazine advertising that goes directly in exploring the market leader position in the segment and saying what the consumer wants to hear. Since Kodak Brownie nº2, launched in 1901, it has been known that amateur photographers want to record their travels, family and friends. The name Trip already introduces the concept. Then the text explores ease of use, the assurance of good exposure thanks to the red lock and optical quality. Very easy to advertise such a good product!

Selling in millions, the Olympus Trip 35 could even afford to campaign on television. Below is a humorous commercial where an old-fashioned photographer, still using a view camera to take a wedding photo, is surprised by a young man using an Olympus Trip 35. The funny thing is that he says that with that camera the young man would never be a professional, however, it was David Bailey, a British photographer who was a celebrity at the time, popularly known. It is even known that for Antonioni’s classic film Blow-Up, whose main artist is a fashion photographer, the director was inspired by the real character, David Bailey, to create the role played by David Hemmings.

Today, more than 50 years after it introduction, the Olympus Trip has become a favorite among beginners in the ongoing renaissance of analog photography. In its time, it was the entry camera, or camera for families and amateurs in general. I even believe that Olympus, with the Trip and the Pen, became so established as the amateur camera brand in the 70s that this hindered the expansion of its excellent OM monoreflex line among professionals. But we cannot forget that from the beginning it already enjoyed the aura of a cult camera. David Bailey himself actually used it, among many others, of course, in his authorial production. Martin Parr was another who exploited Trip’s practicality and reliability for hundreds of his photographs documenting bizarre moments in street snapshots. Don McCullin, Daido Moriyama, William Eggleston, Tony Ray-Jones and many others helped make Olympus Trip famous.

What is behind all this is the fact that versatility, the idea of a camera capable of taking all types of photography, in any situation, does not correspond to reality. Practically no photographer does it all. There were even cameras with this claim. For me, the classic example is the wonderful Linhof Technika line. Its position was precisely to do everything. But that made it slow and cumbersome for a fashion photographer, limited for an architectural photographer, indiscreet for a street photographer, complicated and expensive for the amateur, and so on. The Olympus Trip is great, as mentioned above, for well-lit scenes and subjects between 2 and 5 meters away. If the genre of photography you want fits well in that space, then it is a perfect camera.

In short, if the camera is well built, if it is reliable, and if for the genre of photography the photographer does it provides the minimum of controls, no more and no less, then it is a great camera for that photographer. The Olympus Trip 35 was just that for a legion of amateurs, artists and even professionals.