Retouching desk

This is the ancestor of all image editing software. The “realism” of photography is often mentioned, at the time of its discovery, as its major advantage over painting. But it is also possible to find quotations that consider this realism as one of its greatest shortcomings. Let us take, for instance, one of a very important photographer and photographic lenses manufacturer, the French Noël Marie Paymal Lerebours (1807 – 1873), in his photographic treatise of 1843:

“But the most formidable enemy the Daguerreotype has found is unquestionably human vanity. When one is painted by ordinary means, the complaisant hand of an artist may soften the rather harsh features of the physiognomy, relieve the rigidity of the posture, and present his sitter with grace and dignity. There we find, above all, the talent of the portrait painter; we ask for the likeness, but what we want is beauty, two frequently incompatible requirements.”

We ask for likeness, but what we want is beauty! That is why, as a result of the invention of photography, soon came the means of circumventing its often uncomfortable realism. Daguerreotypes were colored and retouched, but it was in negative / positive processes, initially the calotype, that retouching actually found safer means to flourish and spread fully.

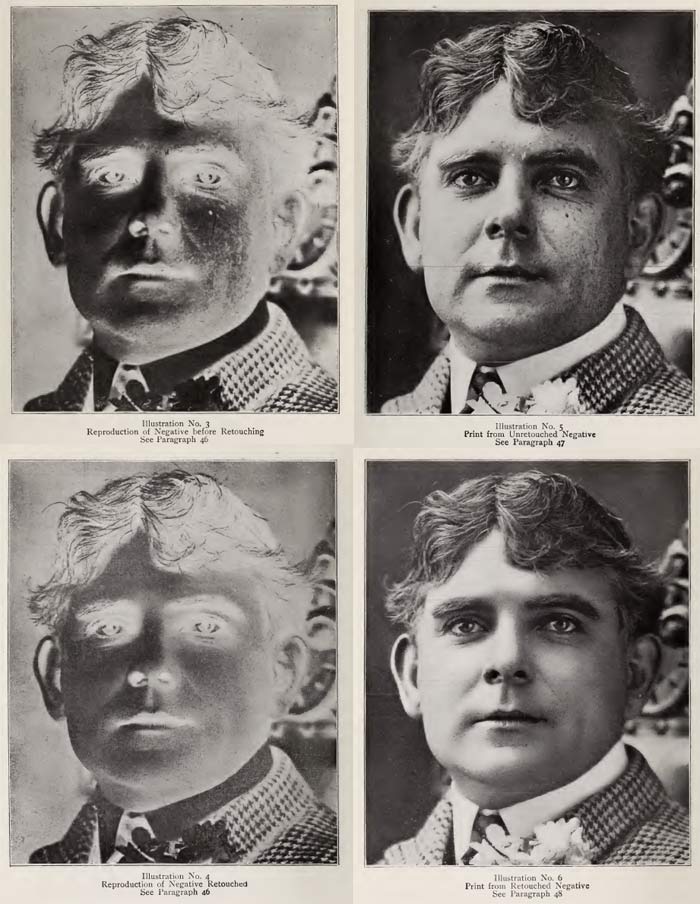

Chemicals were used to lighten areas of the negative in an action known as “reduction”, and also by scraping the emulsion to give it transparency. The opposite action was about adding negative density to brighten areas in the final print. The treatment was carried out directly on the gelatin, starting with reduction or scraping operations, which darken areas of the final pictures, and then a protective varnish could be applied before the final phase with darkening through retouching with pencils and pigments. As wrinkles and other blemishes usually appear as lines or light spots on the negative, by darkening them it is possible to obtain an evening effect and rejuvenate or even correct the sitter’s figure. In the very common case of using pencil, it was often necessary to apply an abrasive to roughen the surface preparing it to “take” the lead. Less aggressive was the common application of a dope onto the emulsion surface. See the formula and use of dope in this specific article about negatives retouching. In these operations the “retouching desk”, previous to the electric light, was the tool of the professional or dedicated amateur.

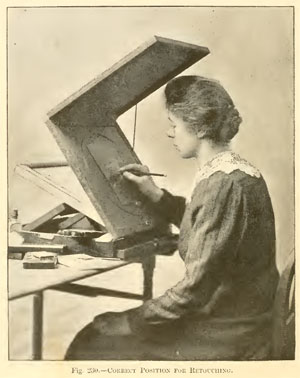

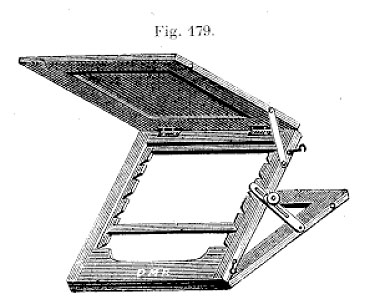

The operating principle is to take advantage of existing light. In the horizontal part there is a mirror that receives light from a window or directly from the sky when working outdoors. The inclined part is a ground glass on which the negative is placed with the emulsion up. The top provides a shade to improve the negative view by avoiding undesirable direct light.

For retouching, the classic material used to darken bright spots like freckles and wrinkles in portraits is the ordinary pencil. However, in general, the emulsion surface is not rough enough to bite the lead. It then needs to be prepared with a “dope” based on Dammar gum.

This table (picture just above), is a very simple model and does not have a bar to hold the negatives on the inclined glass and prevent them from sliding down. The illustration below, taken from the book Prix-courant illustré des appareils photographiques, fournitures et accessoires divers Radiguet et Massiot (Paris) 1901-1902, shows another with this very useful feature (like the one in the first picture in this post).

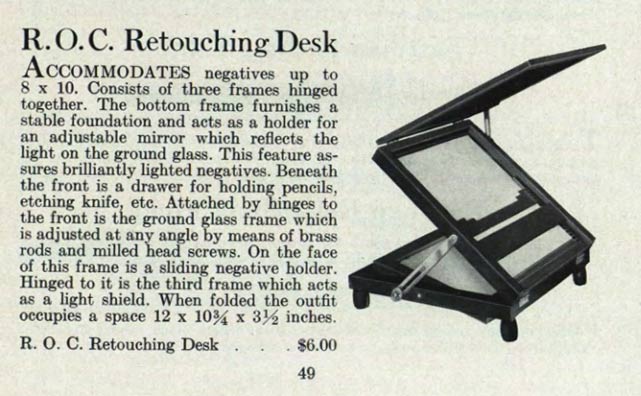

In French the device is called pupitre, which means a inclined table-topped furniture usually used to place books, musical scores or simple for writing. In English, It is common to find in the literature R.O.C. Retouching Desk, where R.O.C. means Rochester Optical Company, purchased by Kodak in 1903.

This model from R.O.C. has, in addition to the support for glass negatives, a mirror that can be regulated in different angles. Some desks also came with a convenient drawer to store photographer’s retouching tools.

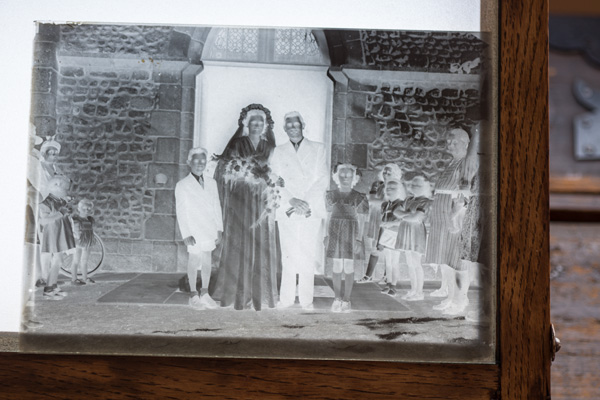

It is very interesting, when you observe old negatives, to search for interventions that were probably made on retouching desks like this. Below is a glass negative, 13 x 18 cm with a wedding photo photographed on the retouching desk.

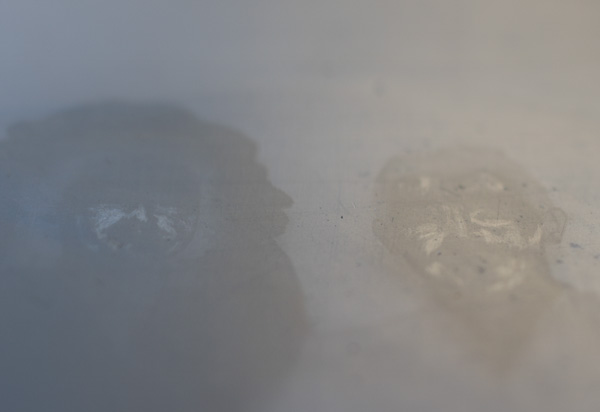

The bridegroom’s face has about 6 mm in height (a quarter of an inch), and even so, when we look at its emulsion side:

We see that the photographer worked a lot on expression lines. Although the retouches are practically imperceptible by transmitted light, taking the photo at an appropriate angle, the difference in brightness/texture denounces several changes made probably with a pencil.

It is impossible to say what the photo would look like without the retouching, but in any case, the final result is very balanced and pleasant. It is difficult to gauge the naturalness of the final result because our eyes are not “trained” to the standards of the time, but it does not seem at all artificial, as the excessive sharpenings of today often seems to us. The image above is a direct scan of the negative in which only the dust on the scanner table and small scratches have been corrected.

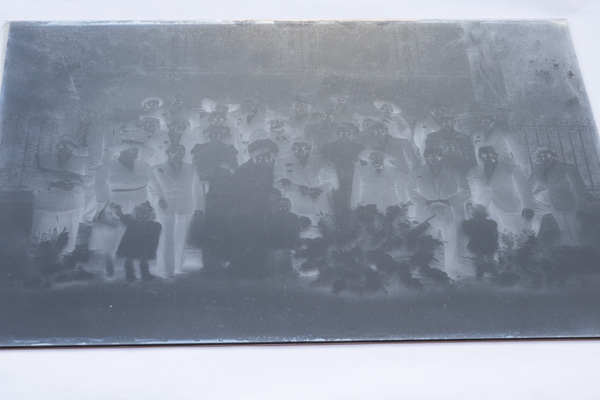

The skill of retouching photographers was such that even in a picture with thirty-three people they could improve the appearance of each one. We can even speculate here about the longevity of the large format in times when roll films such as 120 already existed and were certainly much more practical at the time of shooting. The negative above is a glass plate and has 18 x 24 cm. Retouching at that time had no “zoom”, as in today’s digital, so the retoucher was always working at 100%, physically. In that case, using a larger negative made the task much more comfortable and under control.

There was the direct retouching on the print as well, however, this was left to correct printing imperfection themselves. When it comes to beautification, it is easier, in the analog world, to work the negative instead and, at the moment of printing, let the maximum of matter be that of the gelatine itself, avoiding marks and changes in brightness and / or texture that retouching over the print easily engenders.

Below is a detail from the previous photo showing the retouched faces . The person down on the left in the photo is the groom. The hat girl is on the left, in the photo above, and on the right in the photo below.

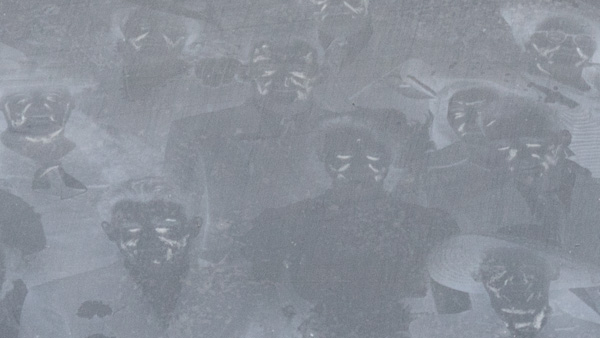

Next is a local scan in the same group. The plate is in good condition and no digital retouching has been done in this scan. It is interesting to note the subtlety of the work on softening shadows and lines of expression on the faces of those portrayed. Good retouching does not replace the original image, instead it adds up to it. It keeps what is recorded on the negative and only partially lowers the density of what is undesirable in the final copy.

Looking in more closely, in this girl with a light dress we can see that in the shadows under the eyes and in the lines called “naso-labial folds” there is a slight change of texture that indicates the presence of the foreign material that was deposited on the negative . What happens is that the texture of the retouching assumes that of the gelatin and not directly that of the grain in the photograph. They are grains of pencil’s lead that settle on the roughness of the gelatin.

In any case, since the purpose of the photo was to be a group photo printed probably by contact, the retouching intervention had the desired effect of making the guests nicer and just looking good. No one would do this thorough inspection that today with digital resources we can do. The end result is that these old wedding photos, printed on silver gelatin paper, are really beautiful to be seen and everyone appears just great.

This is a type of retouch that endeavors to lend veracity to an edited image. The goal is that by looking at the printed image someone will not notice what has changed. You will recognize the people and you will believe that on that happy party day everyone looked so nice. But throughout the history of the photographic images other types of intervention had the declared goal of presenting something that escapes from reality without the slightest concern of trying to hide the trick. A tradition of photo retouching, called photo-painting, foto pintura, in Brazil, falls into this category. In this case, retouching is performed directly on the final copy and is not at all subtle. Adding to this, the digital medium has opened new frontiers for the portraitist to make the joy of his clients. A small sample of this tradition and its renewal is shown on the page Popular Portrait, in peace with fantasy.