Klito nº3A | Houghton Ltd.

This is a camera for dry plates, ie glass plates sensitized with a layer of silver gelatin. It closely resembles the very popular box-camera category, such as the Kodak Brownie Nº2, which is also a box with a front-facing lens and two viewfinders, one for landscape format and one for portrait, but in reality they belong to very different worlds in the history of photography. Klito was like the closing of an era and Brownies opened up a new one.

Both types use the same photographic gesture typical of waist level finders and both can be loaded just once and make multiple photos. Kodak, for example, makes 8 frames in 120 film, while Klito # 3A uses up to 12 preloaded glass plates. This was new, since glass plate cameras usually received one plate at a time, and framing was done in ground-glass, always with a tripod and the iconic black cloth (to see an example of one of those, follow this link: collodion camera).

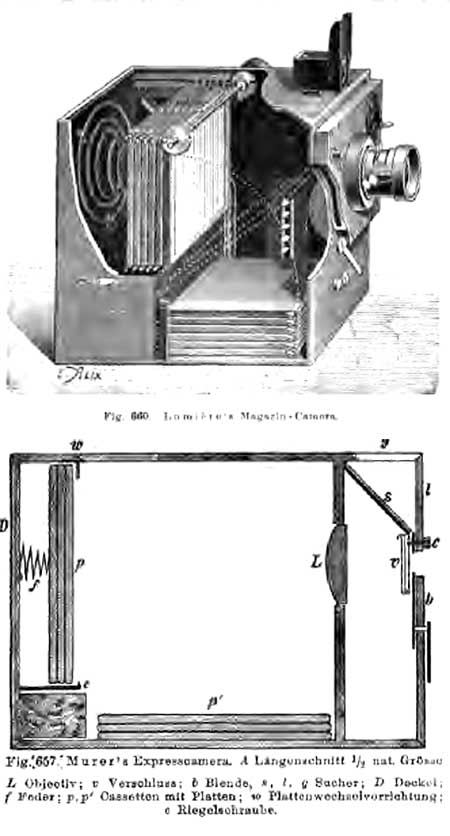

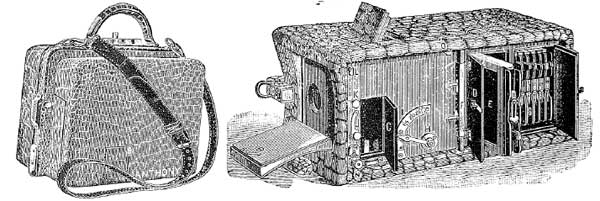

The system for loading and tripping the 12 plates is very ingenious and the illustration below from the book Ausführliches Handbuch der Photographie by Josef Maria Eder ( 1892), shows how it works.

The plates p are loaded in darkness by a rear door D and are se in upright position. When this door is closed, a spring f presses the plates against stops that position the first of them in the focal plane of the L lens. Once exposed, a lever on the top of the camera, next to the strap, is slid to left and the plate falls over the stack of exposed plates, p‘ in the illustration above.

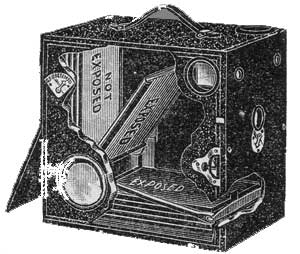

In this drawing from an 1899 Conley Quick Shot, we see the moment when the exposed plate rotates and falls onto the stack at the base of the camera. The systems vary from one falling plate to another and many have been patented. A very useful advantage of this system is that, unlike film, we can load the camera with as many plates as we want up to the limit, 12 in this case. We can still do as in a continuous system and keep developing and loading as we shoot while maintaining a constant buffer of 12 plates. Thus we have the advantage of roll film, which is that it can carry multiple negatives at once, and also the advantage of film plates or sheets, which is that it can have its plates processed one by one.

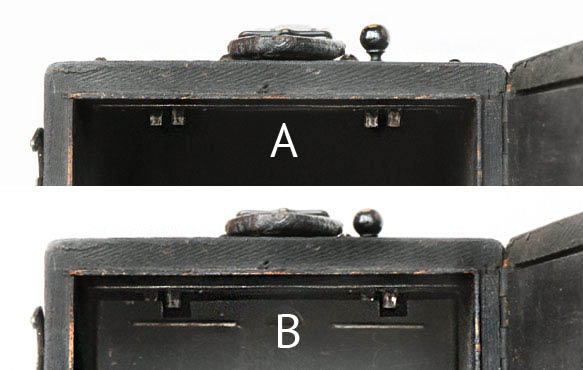

This Klito # 3A even has a split rear door that facilitates the removal of exposed plates without any interference with the still virgin ones.

By pushing the lever on the top and outside of the camera, the two teeth shown in the picture above at A slide to the right. In B we can see that the first one, the one on the left, enters the slot in the plate holder and releases it to topple over the stack. Meanwhile the second one on the right holds the next holder. Upon returning to the starting position we have a new plate ready to be exposed.

At the base of the plates they are secured by a downwardly facing claw (C). Thus, when rotating forward, they are released and fall onto the stack (D).

Interestingly, although it may seem like the type of failure-prone mechanism, in practice it is very reliable and accurate. The extra space it occupies is illusory. Important to note that this camera does something equivalent to the quarter plate: 3¼ x 4¼ inch, which roughly corresponds to 8 x 10 cm, and the alternative that was later adopted for the 4×5 ” or 9×12 cm quarter plate cameras, was the external film-holder and these, as a whole, take up much more space.

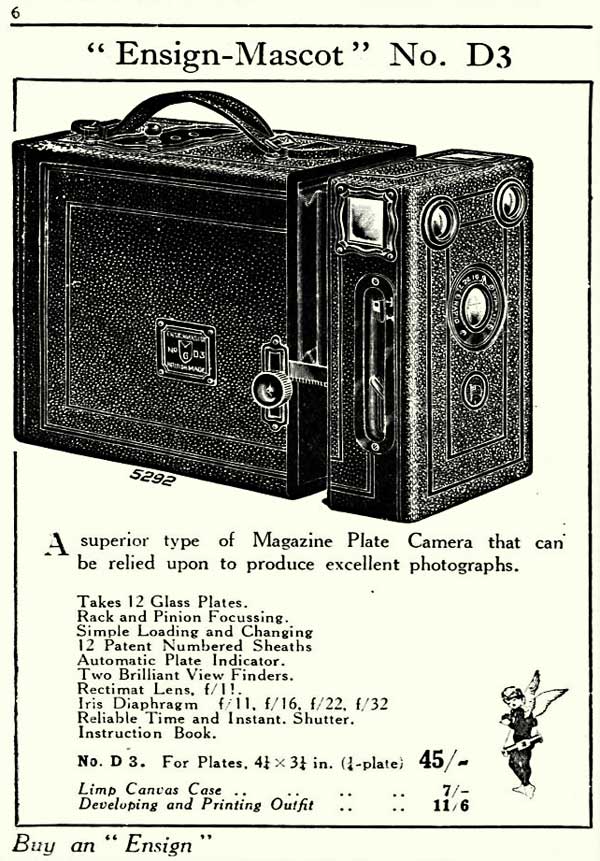

Many were the makers of falling plate cameras, but it seems that the English and Americans had a special interest in this system. Houghton Ltd. was one of the big names in the photographic industry. In London in 1834 George Houghton in partnership with French Antoine Claudet founded Claudet & Houghton. They made glass plates as well as optical glasses and other photographic materials. Later, as Houghton & Sons, they launched the Ensign brand, selling films, making lenses and cameras. It also partnered with another major manufacturer, W. Butcher and Sons Ltd, which was also very active in the falling plate camera market with its also famous Midg line up. So, Houghton was one of the big players in the industry and more details about its parcours can be seen on this site: Ensign Cameras.

Many names for the new gesture

This type of construction is also known as ‘magazine camera’ and we also have the most picturesque ‘detective camera’, as well as ‘falling plate’ camera and finally ‘hand camera’. I consider that the most significant today, historically, is precisely the latter: hand camera, as it came to inaugurate this revolutionary way of photographing. We read in the British Journal of Photography (BJP), November 22, 1889, “A hand camera is primarily intended to take advantage of the rapidity of gelatin plates and the perfect state of rapid shutters, and of the away with the use of an awkward tripod and focussing cloth “.

It is very difficult to determine whether plate hand cameras came before or after roll film cameras. Since it was the roll film that dominated the scene from the mid-twentieth century, we tend to overvalue the emergence of box cameras for films. But I think conceptually the correct approach is to consider that right after the invention of silver gelatin and the commercialisation of ready-to-use plates, which is impossible with wet collodion, the two forms of hand cameras, for roll films or plates, were developments that can be considered parallel and contemporary. If given an advantage, I think it goes to the plate cameras. In the above-cited 1889 BJP article, the author comments: “But as we have not yet obtained a perfect flexible negative film, the greater number of hand-camera users are content—nay, prefer to use ordinary glass plates.” Perhaps simply because, beyond these necessary improvements, the roll-film camera meant two bold steps at once, leaving the tripod and the glass plates, the falling plate hand cameras had some initial advantage as they provided a smoother transition. .

About the name detective camera, in the same article the author comments: “The name ‘detective’ has been given to this class of camera, I know not why, for I have never yet heard of a detective using one, or of any photographs taken with one being used as evidence in a police court, but it seems likely to remain, though for my own part should be glad to see it replaced by the term hand camera”.

But the fact is that the type of construction was soon perceived as very convenient for indiscreet photos and that’s where the system made its entry into photography. In an article in the 1892 American Journal of Photography (AJP), entitled ‘A plea for the hand camera’, we can understand that this was more or less its origin to where it moved from there: “First, let us remark that we approve of the incoming term hand camera, because in its progression and perfection, this sort of camera is in many instances developing out of the purely detective instrument, which it was held within the confines of in its earlier forms. The departure from the concealment of its purpose, by enabling the use of a lens better adapted for making agreeable pictures, for instance, we consider a great stroke in its favor”.

Losing the camouflage

The market for handheld cameras disguised in other objects, such as the one above in a crocodile bag, presented in the New York distributor Anthony’s catalog in 1892, attracted many enthusiasts, detectives or not. It was a kind of initial call to the concept that would not be well received as a substitute for the well-established apparatus of the dedicated professional or amateur photographer. But the photographic possibilities of a camera without a tripod, focus by the viewfinder and capable of taking snapshots, soon opened a much larger horizon.

Of this, it is interesting to note in the quotation above, by Xanthus Smith, in his ‘A plea for the hand camera’, when he talks about lenses, and that by abandoning the idea of camouflage, hand cameras could use lenses that yielded more “agreeable pictures”. Detective cameras were supposed to use a wide-angle lens to include as much of the scene in front of them as possible. This was desirable because the photographer operated the camera undercover and the framing was just a rough estimate. A wide angle would ensure that he would not leave the subject off the picture. However, aesthetically, the wide-angles were not much appreciated, especially for pictures of people, for their inherent distortions. Thus, the hand cameras, which were intended to photography with some aesthetic ambition, opted for longer lenses, more in line with the preferences of that time. Preference that persists to this day, but that may change, due to the influence of mobile phones that use mostly angular lenses.

But even getting longer lenses and assuming the photographic act, the possibility of flirting with candid photos taken without the awareness of people being portrayed was not completely abandoned. In the BJP article, the author comments: “To obtain secrecy, many ingenious dodges have been adopted, and I think this is perhaps a point best left to the user ; but I have found that a box merely painted dead black has been the object of remarkably little observation, far less than I expected”. This desire to still preserve some of the discretion of the early detective cameras contributed to giving the falling plate hand cameras a special charm. In order to be able to install a better, brighter lens, and a more versatile shutter and yet preserve the look of a “box merely painted dead black”, many models, like this Klito Nº3A, have a front door that reveals behind its apparent austerity, a luxurious interior with wood, levers, polished metal mechanisms that resemble jewellery boxes. It’s a secret access, reserved only for the photographer, like those little private, portable altarpieces from the Middle Ages.

But the resistance was great. Since Talbot and Daguerre photographing had been somewhat grounded between the arts and science. It also involved a scenic aspect, demonstration, entertainment. It could be placed also among the curiosities and wonders that so much excited the nineteenth century. The photographer was jealous of his image of a scholar, an artist, able to move between chemistry, physics and the fine arts. Photographing was an event in itself and needed a mise-en-scène to match its ambitions. The traditional photography with ground glass, black cloth, tripod, and even the darkroom lab, where the wet collodion plates needed to be processed immediately, provided all this cherished conceptual space.

The contempt for hand-cameras came initially, as one might expect, from the photographers themselves. But in the literature of the time, publishers and manufacturers (read advertisers) collaborated to take photography out of this ‘hidden science’ territory into which it had entrenched itself. On this, it is worth a long quote from the opening of the article ‘A plea for the hand camera’:

“Having noticed in some articles published lately by writers about cameras and photographing, a disposition to speak disparagingly of hand cameras, as detective cameras are now often called, and of hand camera work, we would feel disposed to say a word or two in their favor.

The idea which these writers would seem to wish to convey is, that any work which is done in photography other than with a camera well secured upon a tripod is mere trifling, and altogether beneath the attention of the would-be artistic photographer – who, they would lead you to suppose, is invariably to give so much concern to the selection of his subject, and the focusing and exposure, that any apparatus which does not admit of being screwed to a table-like support must be considered entirely inadequate to the production of valuable photographic pictures. The going about with a trifling little box, though it may appear formidable in its complexity of screws and registers, dials and triggers, and sapping away at whatever presents itself to you as curious, it is mooted by some, is employment suited only to the half-witted enthusiast or the school boy, and should be frowned down by the legitimate photographer, who sets his art above such light accomplishments as sporting with a hand camera.”

I love the amusing irony with which the author scoffs at the strategies for adding respect, seriousness and an artistic allure to photography.

In the same article it is clear that this unmasking of the enthusiastic professional or amateur photographer, when they hid behind complex procedures and equipment to make their work more prestigious, was aimed at the popularisation of photography. It was around this time that it began to be seen as an activity that could be simple, fun and within the reach of a much larger audience. Photography could be an accessory, a complement, a short break from a tour, event, or trip, without the amateur photographer having to carry tons of equipment or understanding of the physicochemical processes involved in producing their images. The author of ‘A Plea for the Hand Camera’ points out how much it is best suited to “one of the most extensive branches of photography now, and one that is daily on the increase, is that of the tourist”.

On the possibility of making good photographs, even with some artistic value, with a hand camera, Xanthus Smith comments:”It must be remembered that if a great many persons who are lacking either in good taste or in some art culture, and who use detective or hand cameras, take innumerable inartistic and indeed often very absurd pictures, it is not the means that is to be blamed, but the individual instead”.

Finally, in rolls or plates, it was with hand cameras that came the transition from “seeing to photograph” to “photograph to see”. The last recommendation in the AJP article goes well in this direction which is today a photography paradigm when you’re more photographer in editing than while shooting. “With those persons who are so fortunate as to possess both ample time and means, we would say fire away, do not miss a chance that would seem likely to result in an interesting picture, and subsequently destroy those negatives which are undesirable. The less favoured will have to be more wary, and rather take the risk of losing a picture than wast their material”.

The lenses

Many falling plate hand-held cameras used, just like most roll film box cameras, a simple meniscus as a lens. They usually had the iris in front of the optics thus using the configuration of the very first lenses for landscapes. I have not found in the literature references to the use of achromatic doublets in falling plate cameras. The next step was a Rapid Rectilinear (symmetrical 4 elements in 2 groups) as the BJP article attests: “we will at once recommend the rapid rectilinear type to those who can afford it, and the single non-achromatic lens to those who require a cheap form.”

In this Klito nº3A is installed a Rectimat Symmetrical Lens probably manufactured by Ensign. The aperture is f/11. The focal length, taking advantage of the fact that the RRs are symmetrical, was measured with a ruler from the plate to the lens center and gave something like 155 mm. The diagonal of the 3¼ x 4¼” frame is ~ 135mm. So it really works like a normal lens and not angled. Its viewing angle is ~ 47º.

The times offered are 1/100, 1/50, 1/25, B and T. The piston that appears at the top is not a retarder, it is simply for a pneumatic remote actuation. About the times used, at the BJP article, we find interesting remarks: “It is sometimes necessary to use a tripod for time exposures, and then the one which folds up as a walking stick will be found very convenient, for general work it is as well to be independent of it, for it is quite possible to hold the camera steady for half a second. I have one or two sharp negatives taken with this speed. One-fifth of a second makes work a little more comfortable, and with one-tenth of a second one may depend upon sharp results without much care being taken in steadying”. The box shape and waist level finder really give good stability, but 1/2 second is far from today’s standards for what we call hand held photography. Maybe our fast emulsions made us lazy.

The focus

The most sophisticated falling plate hand cameras use a rack system to focus. Others offered supplemental lenses that slid in front of the meniscus for 3 zones of shorter distances. Those using a Rapid Rectiliear usually have a small bellows and advance something like an inch.

This is sufficient to focus on objects from 7 feet away. Needless to say, these are not close-up cameras. Distances smaller than this, although viable from an optical standpoint, are impossible to frame correctly with a viewer without parallax correction.

In use

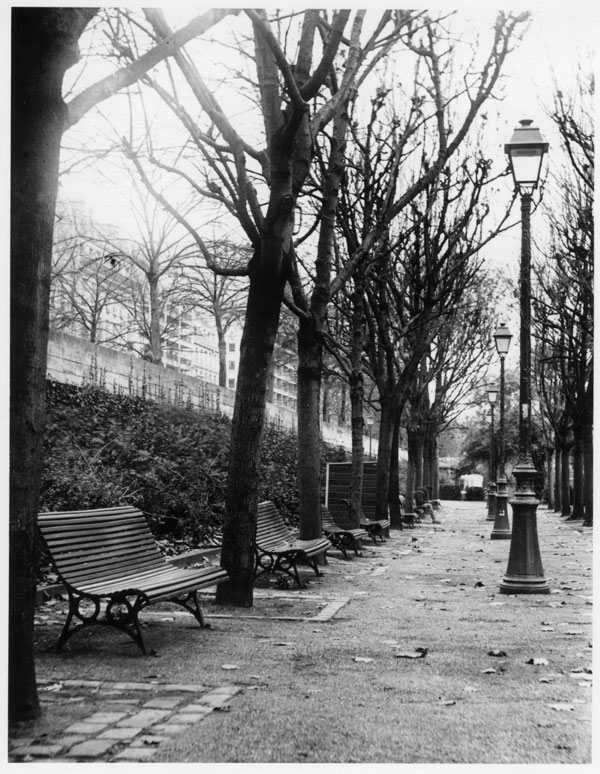

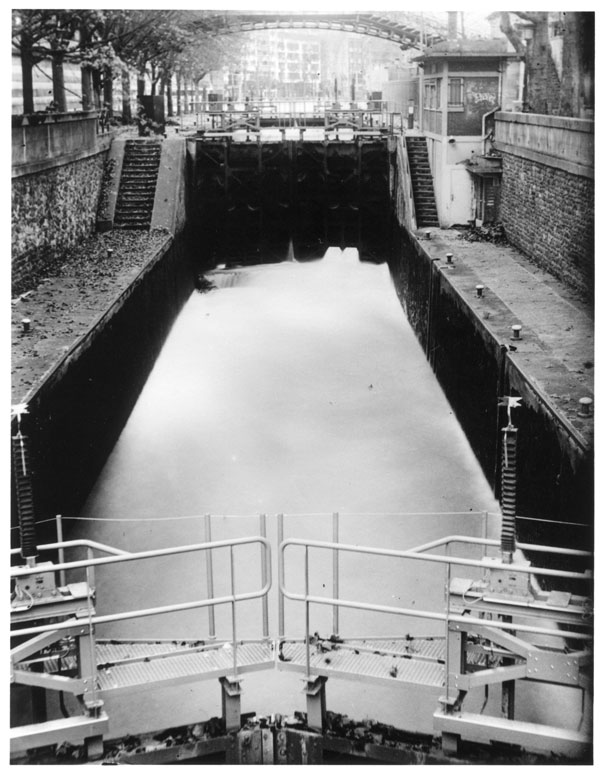

Since late 2017 I have been making dry plates, silver gelatin-sensitized glass plates, produced by a small-scale, homemade method. The camera was bought in Germany and it was already complete and needed absolutely nothing but the plates to be put to work. As stated above, it uses the 3¼ x 4¼ format, approximately 80 x 100 mm, on 1 mm thick glass sheets. I cut some that I had in 9 x 12 cm (much more common). For me this is great because usually, after printing what worth it, I remove the gelatin and reuse the glasses again and again.

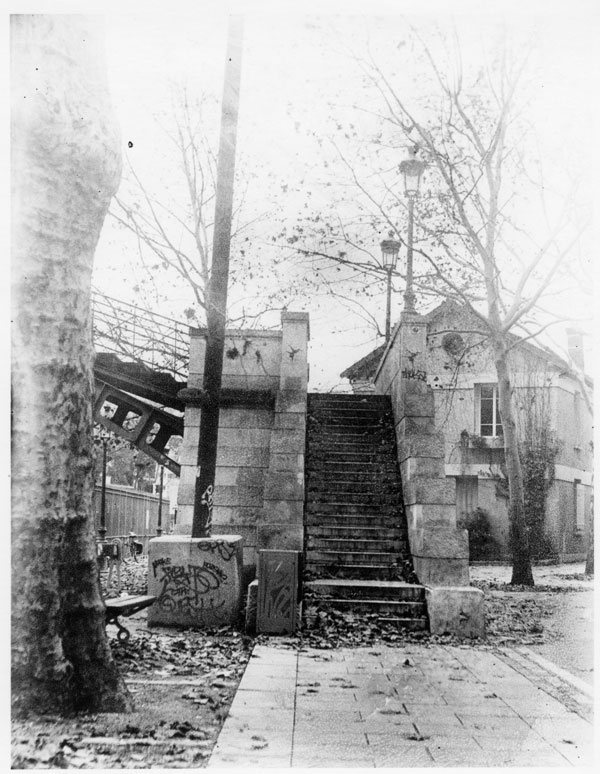

The emulsion I prepared is sensitive only to blue and UV and did not allow, on cloudy days when I photographed, not even use 1/25 s at f / 11, which is the maximum it gets for low light situations. That’s why I needed a tripod, contrary to the key camera concept. Another problem with the homemade plates is that they did not have an anti-halo treatment and it was very evident the light that the emulsion itself spread was bounced on the second glass surface. That created a very strong halo in the sky region, as it can be seen in these printed photos, even after a lot of local burning.

But even considering these problems I was very pleased with the result and especially with the practicality of using this camera. I will definitely continue to use it and keep trying to make plates that will allow me to give away with the tripod.

Very nice. It is hard to find information in general on Falling Plate cameras as a whole and your article is very detailed and informative! Of course, now I want one! Thank you for this article on a format that is severely underrepresented online.