Ikonta and Super Ikonta | Zeiss Ikon

Glass plates and roll film, two different worlds

The 1920s marked the final turn of roll films by taking the lead of glass plates or sheet films. Since the late nineteenth century, with the successful introduction of the Kodak Brownie, among others, the roll films had been established with a large and lively market. But there was still a mindset that more dedicated photographers, amateurs or professionals, would be better served with plate cameras. In the meantime, more feature-rich, better-lenses, more convenient roll-film cameras began to emerge, and these eventually dominated photography in the following decades. The Ikontas of the newly formed Zeiss Ikon were very important in this transformation with regard to medium format photography.

The main advantage of glass plates was rooted in the way photography was known from its earliest days. Each photo had always been treated individually. The photographer’s unit of work was the plate and each one should be exposed according to light condition and subject. It seemed inherent in photography that each click triggered a unique process that would go up to the final print.

For negative development, the emulsions allowed the use of red/amber light in the darkroom and gave to the photographer greater control while observing the process. That was the possibility of adding an accelerator, a restrainer or even working each negative locally according to his aesthetic intent. This development by inspection was far more productive with individual plates.

Negative retouching over large and flat ones, was much more effective than in curly and smaller negatives, in the case of roll film. Photographer usually modeled, made backgrounds, added or eliminated props and accessories. In particular wrinkles, stains and age marks were also minimized in this way. Many nineteenth-century photographers had a background in painting and drawing, and retouching was a technique considered mostly artistic and part of the photographic process.

All of these factors worked in harmony with an idea of “non-automation” of the process. The gesture of the photographer, the photographer as an artist, depended on his talent and intervened at all stages. He was the one who prepared his chemists, the camera, the light and the scenery. He directed the click and developed the negative in a very manual fashion. Like a painter, he retouched it and also intervened in the positive print. His work depended on knowledge and dexterity that made his art a profession and his profession an art. This view had a considerable bearing on the continuity of plate films and especially glass plates that persisted in commerce until late in the twentieth century. That was the identity of serious photography. Perhaps the same reasons are also behind the current revival of analog photography.

Whereas for the amateur, on vacation or at a family gathering, the idea of a more portable camera, complete with several photos that could be developed all at once, had many advantages. This audience was not so interested in the photographic process itself. Being able to send the roll to a specialized lab and get their prints ready, was more than enough involvement for the weekend photographer. The ontological act of photographing, using a tripod, ground glass, black cloth, gleaming brass lenses, all that mise-en-scène followed by the darkroom, were the foundations of the photographer’s “profession”, followed also by the dedicated hobbyist. For the most uncompromising amateur, though it was modern and elegant to photograph, he did not want that to imply a very absorbing dedication there. Being able to take the camera out of his pocket, take some snapshots, and get back to social life was all that the great majority demanded.

One category of transition that was very important in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was the “falling plate cameras” or “detective cameras”. These were the first ones that once dismissed the tripod and the black cloth. Today, a less observant person may even confuse them with a roll-film camera, but in fact they were boxes in which 12 glass plates, in the quarter-plate format, were usually loaded and could be advanced by an ingenious device. The lenses ranged from simple meniscus to rapid rectilinears. This camera is a Klito # 3A, from the English manufacturer Houghton. For more detailed model and category information please visit this link.

Roll film was good, but the cameras…

The problem with the first admittedly amateur cameras was that they showed a quality gulf with professionals. There was a real setback to optics and lens types older than photography were reintroduced. When anastigmatic lenses with openings up to f/4 already existed, the amateur had to settle for a f/11 even less meniscus. As this gulf started to fill up, more and more professionals in various applications, finally started to leave the glass-plate and sheet films in favor of the roll format that would dominate both professional and amateur markets. Only in more specific applications has sheet film persisted and persists to this day. Interestingly, I believe that most large-format photographers today are amateurs. More than that, many of these amateurs, like me, are making their collodion or silver gelatin emulsions and so again covering glass plates.

Faster films, better lenses and more functional cameras were key to this change. But the first cameras that risked better features for the general public still had a long way to go in practicality and image quality. As always, they were a little contaminated by concepts borrowed from the world they wanted to emancipate from.

To give just one example, this Kodak # 1A, on the left, offered four diaphragm apertures, shutter with instantaneous, B and T. But it still used a meniscus-type lens, a single concave/convex glass, at a time when much better designs already existed. The body was still wood made and the way the film was loaded required the rear be removed entirely. This camera makes a 2½ x 4½ (~ 63 x 114 mm) frame in A116 movie format (which no longer exists). An quite large size for a meniscus and o top of that with no focus adjustment. The big advantage was the smaller size when closed. But even though Kodak included it in the Vest Pocket category, it was too big to be in the pocket of even a XL coat. Technically it was a box camera disguised with a beautiful red bellows.

But Kodak # 1A was one of the ancestors of medium format roll film folding cameras and the Ikontas represented their full development into a concept that would only be surpassed much later by monoreflexes like the Hasselblad or twin objectives like the Rolleiflexes.

The new features

As I do not consider that important, I have not thoroughly researched which novelties in Ikontas were in fact the invention and pioneering of Zeiss Ikon. This was probably not often the case as it was a very productive time for experimentation of all kinds by all manufacturers. Despite a patent fever, much was copied or adapted from other camera maker’s yards. The important thing is to observe how a certain combination of specifications, design and brand power have made Ikontas the best folding cameras in the medium format category.

All metal

The Ikontas are entirely metal with black leather outer finish. This allowed a considerable size reduction. It’s probably the least you can get by considering the frame shape itself and lens’ focal length. It was released at 6 x 9 cm in 1929, and soon unfolded into other smaller possibilities of the 120 film: 6 x 6 and 6 x 4.5 that followed. Unlike bulky box cameras, it was in fact a Vest Pocket, as it would actually fit in a coat pocket or a small purse.

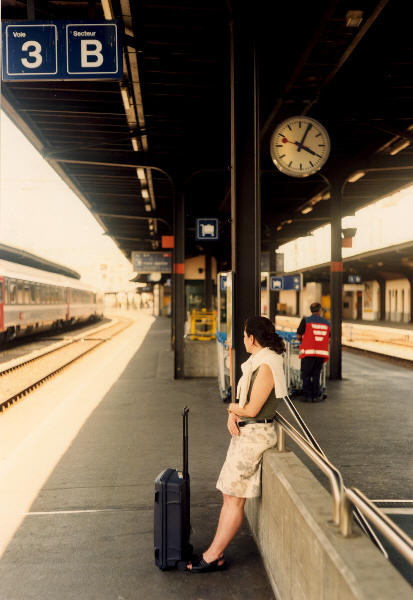

Even today, thinking within the category of medium format analog photography, the size of these cameras is a very interesting point. The photo above shows the Super Ikonta IV in its original leather case. It is too small for a medium format. Bellows and folding cameras may be outdated and even obsolete as concepts for other reasons, but there is no denying the convenience they provide in the camera’s final size. It is a great choice as a travel camera. They are not much lighter than the others, but take up very little space and with a strap they feel like a small hand bag.

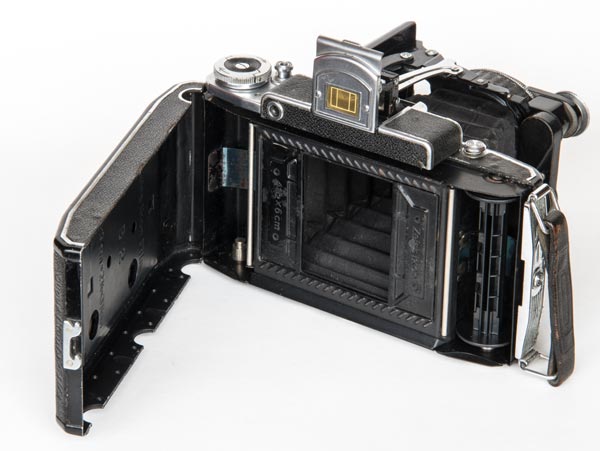

Hinged back

The back of the camera is secured to it by a hinge. This may sound trite, but it is much easier to change the film on Ikontas than on any detachable rear camera as most of its competitors were at the time of its release. Often the photographer is in places where he simply has nowhere to put the back and needs both hands to insert the film reels in place. The ease of film change operation goes far beyond its contemporary Rolleiflexes or Leicas.

Frame counter and film advance

All Ikontas and Super Ikontas have the “little windows” on the back of the camera that is where the film passes. 120 film is the kind that runs along with a totally opaque paper behind it and on which the frame numbers are marked. I believe that it is an excessive care to close these openings, other cameras, such as Baby Box Tengor, had no such addendum and the film was not burned through these windows.

Super Ikonta C features two windows as there were inserts that reduced the frame size from 6 x 9 cm to 6 x 4.5 cm. To take advantage of the same numbering already printed on the paper behind the film, the photographer should pass each number twice, once in the first window and once in the second. Even the 6×6 cm Super Ikontas B, BX and IV with automatic film stop still kept the windows.

In Super Ikonta B, above, we see the frame counter on the left of the film advance button. Since the 120 film is not punched, auto-stop feed is a bit more complicated and is based on the fact that with the full reel the it needs to take fewer turns to advance a frame. Perhaps for safety’s sake, Super Ikonta B only takes 11 photos in a 120 movie and gives a larger frame spacing.

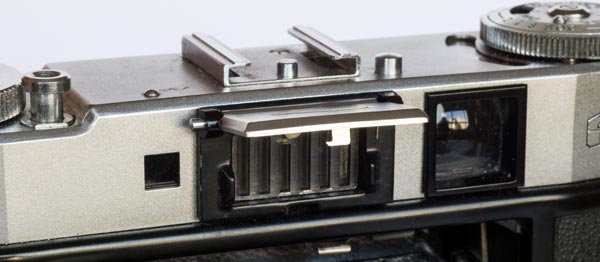

In Super Ikonta IV there is a small window, indicated by an arrow on the right side, where you can see the frame number and in this case it goes from 1 to 12.

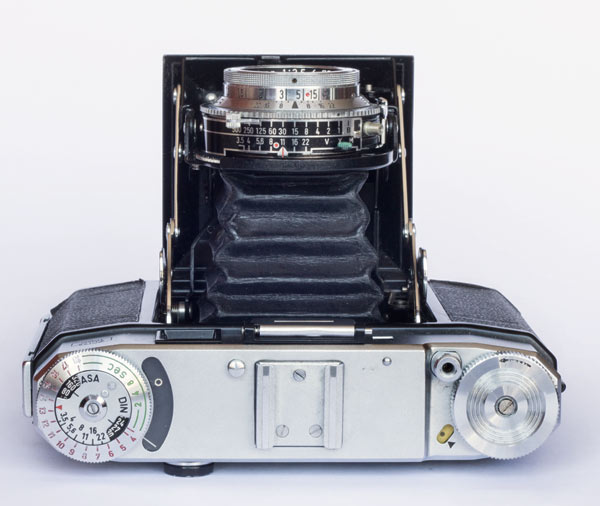

In all Ikontas the advance of the film is made by turning a knob on the top of the camera. Perhaps because of the small size and geometry of these cameras, no other solution was possible, for example, the sleek Rolleiflexes crank or 35mm advance lever.

Opening the camera

Characteristic of all Ikontas is the button that opens the camera. Closed, they resemble a little cigarette case or an office object. But when you press a button on the top of the camera, the lid opens and the lens already advances and automatically locks into position. By doing the reverse operation we can realize the design effort to make everything fit in such tight space. It’s a true contortion that the hinged rods need to do to, retract the lens and close the bellows. It impresses with the firmness with which this structure is positioned without with easy and precision.

Moreover, I believe that this is one of those aspects called “playful”, which delight the user. It also has the association with the cocking of a firearm ready to fire. This association is so recurrent in photography where the capture of the image symbolically evokes the shooting down of a hunt.

Firing the shutter

Roll-film camera lenses usually incorporate a shutter, that is, it was not something loose or installed in the camera body, as in focal plane shutters, for example. What was not consensus at the time is how it should be fired. Due to economy or inheritance of view cameras, this was often done by a trigger cable or directly on a small lever on the lens. Thus occupying a hand that could be helping to hold the camera firmly. These systems practically required the use of a tripod. It seems natural to us today that when holding a camera in order to look through its viewfinder and compose the photo, the shutter button should be right where our index finger is positioned. This was the condition imposed on the whole series of Ikontas and Super Ikontas. As the ad reproduced below, for a Super Ikonta B: “Perfect control – simple, effortless operation that lets you concentrate on the picture instead of the camera.”

Optics

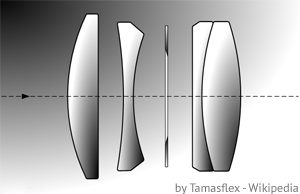

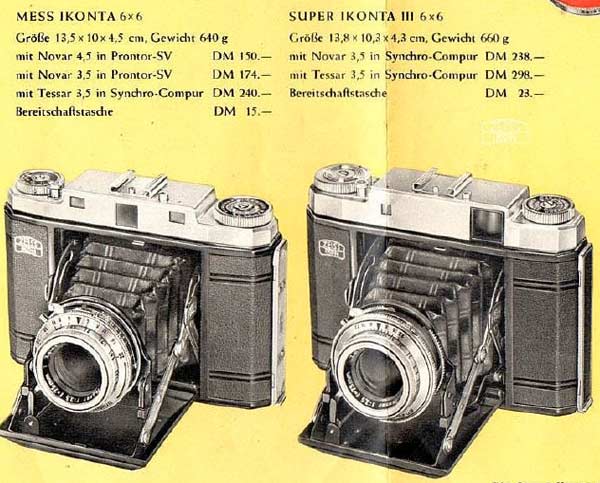

The lenses in every series of Ikontas and Super Ikontas were invariably of two types Tessar or Novar. Perhaps there is some exception because it is amazing how easily variations were introduced and recombined parts and pieces. But that was the rule. Tessar to the more sophisticated, commanding a higher price, or Novar to the baseline. There was a temporary replacement with Schneider Xenars, which will be mentioned below.

Tessar is one of the happiest drawings in the history of photography. Under different names, it was produced by the millions by all twentieth-century photographic optics manufacturers. Relatively simple, with 4 elements in 3 groups, it performs very well with flat field and great contrast even before anti-reflex coating. It was a lens produced from very short focal lengths, 50mm for 35mm cameras up to 600mm for extra large format cameras. For more complete information, visit the Tessar – Carl Zeiss page.

Novar is a triplet, three lenses in three groups. This is a lens that apparently was not manufactured at long focal lengths, did not participate in the large format professional market and perhaps is therefore difficult to find technical and historical information about it. Another complicating factor is that at that time, when a name gained a certain brand value, it was often transferred from one discontinued product to another that would be released. According to Vade Mecum this name was for a double anastigmat in Hütting lists – a manufacturer of Dresden in the early twentieth century. Hütting was absorbed by I.C.A. in 1909 and it later became one of the four big ones that formed Zeiss Ikon in the 1920s. Novar, definitely a triplet at Zeiss Ikon, existed at f / 6.8, f / 6.3, f / 4.5 and f / 3.5, always in short focal lengths for medium format. It was also lens for enlargers.

Zeiss Ikon was the camera manufacturer, different from Carl Zeiss, the optics concern, that exists until today. For each new camera, after defining the specifications for its normally very demanding lenses, a consultation was made with various manufacturers. According to Barringer, in the most sophisticated optics, more than often, Carl Zeiss was the one taking the order. But in the most popular, and this was the case with Novar, it was manufactured by Goerz and also Rodenstock without them having their names engraved on the lens. The only brands to which Zeiss Ikon admitted such a distinction were Carl Zeiss itself and Schneider-Kreuznach.

A well-designed triplet is cost effective because one of the things that make lens production very expensive is the need to cement and center two or more elements to form a group with matching optical axes, such as Tessar and a very tough case like the Protar VII, a 4 + 4, both contemporary examples of Novar.

In the detail of a Zeiss Ikon catalog from the late 1950s, we can see the price difference between the same models when equipped with Novar or Tessar, f/3.5 or f/4.5 and Prontor-SV shutter or the more sophisticated Synchro- Compur. With the same shutter and aperture, Tessar’s inclusion in the Super Ikonta III (which is the IV without a light meter) raises the price by DM 60, ~ 25% more expensive.

About Novar, it is worth noting that today there is almost a cult of certain triplets such as the Meyer-Gorlitz Trioplan or the Taylor-Taylor & Hobson Cooke Triplet. They have a community of fans due to their image qualities, a sharp cutout in the foreground and a nice background bokeh. I think Novar is a good field for experimentation today, as it is equally a triplet, and is much more affordable and higher in availability (usually it comes in a camera). I made photos that I really liked with a Novar 105 mm f/4.5, on an Ikonta 6 x 9 cm (below).

Lens coating

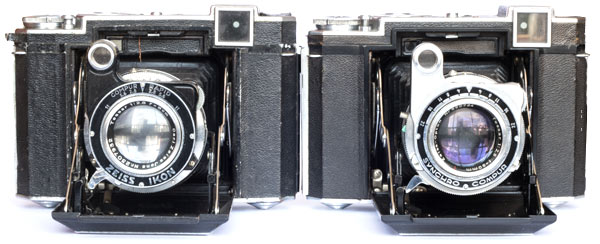

Zeiss Ikon, since the beginning of the Ikontas series in 1929, has endowed them with first-class optics, betting that even the amateur photographer would respond positively to this quality gain, as he actually did. Another example in this direction is that after World War II, with all the difficulties to resume production, a new technology was soon incorporated that further improved Ikontas performance: anti-reflex treatment.

In the picture above we see the difference, at least in external appearance, between the lens with or without anti-glare treatment, the coating. A lens should be a light trap and virtually all light incident on it should be captured for the image on the film. For this reason, ideally the lens should be almost black. The anti-glare layer greatly improves this condition as it helps to make more light transmit and not reflected on the glass-air and air-glass surfaces. The lens on the left is from an older Super Ikonta B, the second shows a much improved transmission coating and is therefore darker.

Focusing

Focusing is perhaps the only objectionable point of the Ikontas and Super Ikontas. But it is due to the camera’s reduced space and concept. To focus on close objects, Tessars and Novars, like all lenses, need the entire optical set to advance from infinity position towards the subject. However, Zeiss Ikon chose to advance only the front element.

At Nettar, above, as we rotate the front ring to focus on closer objects, the rear assembly with the two rear lens, diaphragm and shutter remain fixed. This means that the bellows do not need to expand and the whole is much more rigid and reliable. But that is the plus point.

According to Kingslake: “The foundation of this choice is that moving only the front element the required displacement is only 1/9 of what it would be for the lens as a whole. It can be noted that even if the front lens is advanced not much more than 2mm, the focus will come to something like 1.20 meters from the camera.

What comes out of this is that with all these cameras, not just the Ikontas, where we observe that it is only the front element that advances, we must avoid shooting landscapes with the lens all open. Closing the diaphragm compensates for over correction in the infinite position. Recalling that spherical aberration, under or over corrected, affects the image periphery more strongly. This is an issue that affects almost all medium format folding cameras of the time.”.

The models

According to Tubbs, the first Ikonta was a 6×9 cm launched in 1929. Equipped with a Novar 105 mm f / 6.3 and an everset-type Derval shutter (it does not need to be cocked). T, B, 1/25, 1/50 and 1/100 s speeds. From there, within the same general concept, many variations were added. In 1960 was produced the last of the dynasty, Super Ikonta IV. That’s when Zeiss Ikon decided to focus on the 35mm film camera market.

It is impossible to go into the detail of all combinations here. Here is a list of the main features of the various models:

Names: Always Ikonta or Super Ikonta followed by a Roman letter or number and an exact model identifier code. Nettar is an exception, but it was included here as it follows the concept of Ikontas. It seems to be just a special name as it is always a camera with more basic specifications. The manufacturer was Zeiss Ikon, not to be confused with Carl Zeiss who was the group’s optical manufacturer. Eventually Zeiss Ikon bought lenses from other brands.

Common to all: Hinged back, auto button-open, direct viewfinder, shutter release on top of the camera body, all-metal covered with black leather or imitation on popular models. Focusing by advancing front element only.

Formats: 4.5 x 6 cm referred to as A, 6 x 6 cm referred to as B and 6 x 9 cm referred to as C. There were others at the beginning of the line, but those that used 120 film became the focus and others were discontinued.

Ikonta x Super Ikonta: The latter were introduced in 1934 and had a coupled rangefinder, that is, a range finder that automatically adjusts the focus of the lens. In format B, 6 x 6 cm, the rangefinder was on the display itself. In A and C range finder and display are separated.

Optics: Novar f/6.3, f/4.5 and f/3.5. This design was made for Zeiss Ikon not only by Carl Zeiss but also by Rodenstock. Tessar f/4.5, f/3.5 and f/2.8. The f/2.8 aperture was only available for the size B Super Ikonta. From 1947 to 1952, given the post-war difficulties, Schneider supplied some Xenar f/3.5 for sizes A and B. It was the only firm in addition to from Zeiss, which could put his name on the lens ring.

Focusing: By distance scales on the lens ring on the Ikontas and Nettars. Some Nettars had an uncoupled rangefinder and Super Ikontas coupled rangefinder.

Shutters: Derval, Klio, Prontor, Compur and Synchro-Compur. Shutter features matched the lens quality and sensitivity of the films available at the time of each model. Only Derval had a small range of speeds, from 1/25 to 1 / 100s. The others went from 1s to 1/200 or even 1/500s, case of the famous Synchro-Compur. All of them had B.

These information came basically from:

Zeiss Cameras, 1926-39 – D.B. Tubbs e Zeiss Compendium East and West – 1940-1972 Charles M. Barringer and Marc James Small.

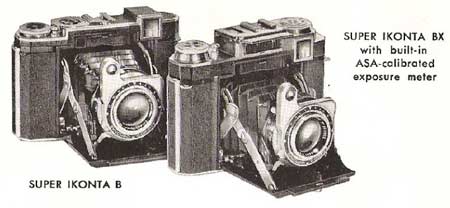

On the left, Super Ikonta B also had a BX option with a Contax IIIa photometer

Accessories

Lacking interchangeable lenses, the Ikontas and Super Ikontas do not have a wide range of accessories. They do not form a “system”, a term that is known for lines such as Leicas, Contaxes and most major monoreflex brands. In addition to the leather case and a very nice set of basic filters, Zeiss Ikon offered some flash options for Flashbulbs. Below is the Ikoblitz 5 for FP bulbs. Nicely constructed, this is a capacitor flash that increases the intensity of the spark that ignites the bulb and thus reduces the chances of failures. The battery is no longer manufactured but there is room inside to install a current battery and capacitor circuit. The reflector, which resembles a daisy, can be closed and the flash fits into the box that appears on the left in the photo.

Super Ikonta IV, the climax

The B format (6 x 6 cm) is interesting because the camera is always in a horizontal position and this, due to its ergonomics, gives more firmness and easier operation. Also, with most modern film, cropping 6 x 6 cm negative while enlarging it, to rearrange the photo as landscape or portrait, does not represent a significant loss in image quality. I couldn’t find data on that, but it was probably the best selling size. We can make that assumption also because Super Ikonta B is the only one with a range finder coupled and integrated into the viewfinder. For all these reasons, it is not surprising that when Zeiss Ikon wanted to redesign its acclaimed folding camera, it chose only the 6 x 6 format. That’s how the Super Ikontas III and IV came in, being the latter with lightmeter.

The latest Super Ikonta has all the best. A coated Tessar, 75mm f/3.5, which features the best balance between sharpness and focus within the focus restriction of moving only the first element. The Super Ikontas B, having a Tessar 75mm f/2.8, was reputed to be very soft at full aperture (Small-Barringer). The shutter is a Syncro-Compur, up to 1/500s with M and X flash sync. The top has been completely redesigned and modernised resulting in an extremely compact 6×6 cm camera. All while maintaining the highest standard of engineering and finishing.

Like all handheld cameras, the best opportunities will be with the photographer who anticipates the light condition he will encounter. The Super Ikonta IV, with lightmeter, uses the concept of EV (exposure value), the same as its contemporary Contaflex. That is not so automatic but has its advantages.

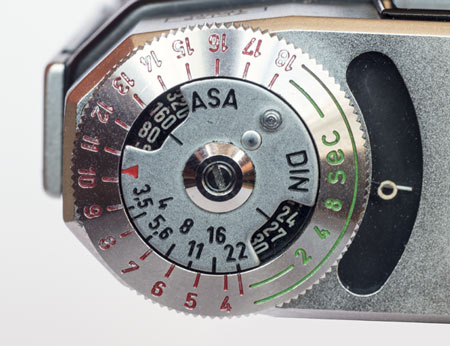

To read it, open the photo cell cover. This cover is very convenient because these cells wear out with light and having this protection their durability is very much improved.

After that, having the film’s ISO set beforehand (which appears as ASA or DIN), the camera is pointed at the scene, and turning the ring causes the white circle to move until it coincides with the needle. At this point the EV number, Exposure Value, is indicated by the red arrow that is opposite the pointer. This number should be carried to the lens as explained below.

After checking the EV number on the lightmeter it must be adjusted to the ring scale in red figures on the lens through the pointer which in the above case is marking 10. From then on turning the ring with that same scale can go through all aperture and speed combinations that conform to this EV. In the top photo we have f/11 and 1/8 s, and in the bottom picture f/5.6 and 1/30s. This system appears on many cameras of the time, such as Contaflex, also by Zeiss Ikon, and has the advantage that after some practice, for a certain ISO, it is easy to memorize the EV for typical situations such as sunny, cloudy, indoors in such and such conditions. There is a single number, a single scale to memorize and from there the aperture and speed combinations are preselected in the camera. With some practice with a certain ISO, the lightmeter becomes even dispensable.

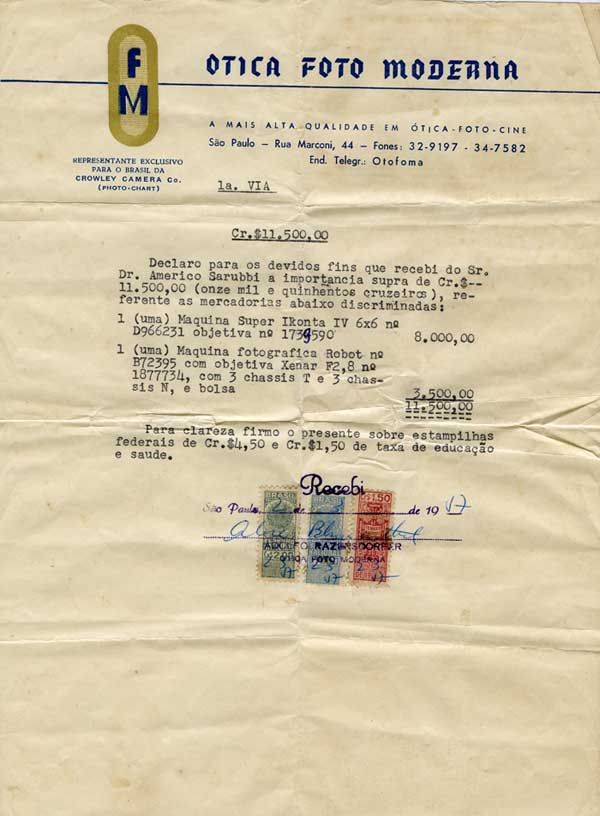

This particular camera was from a friend’s grandfather and it came with the purchase receipt here in Brazil, in Sao Paulo, in 1957. That was two years after its release. It certainly caused a sensation.

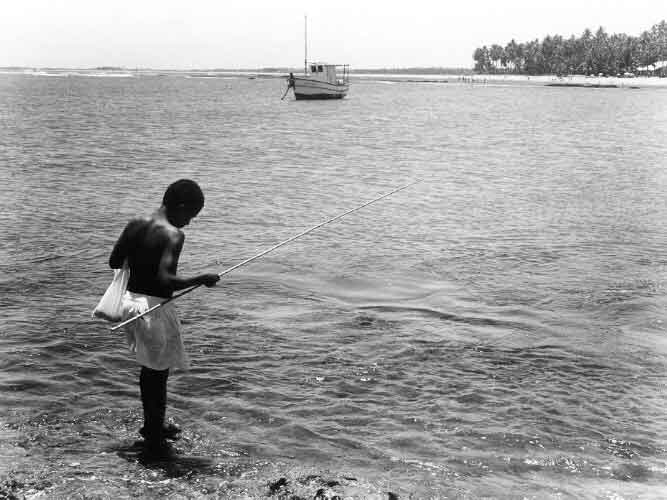

Like all the others, but more than all the other Ikontas and Super Ikontas, this camera is perfectly usable today. If we think of photography in its various possibilities and manifestations, it really just does not escape the weakness of all viewfinder cameras: it is not a camera for close-ups. I would say that in portraits it performs better in full body, half body still works well, but a single face picture is impossible, even because it focuses only from 1.20 m onwards and to fill a 6 x 6 cm frame with only a face with this focal length would need ~ 90 cm. Considering also that its diagonal viewing angle is 60º, a little angular, the perspective for the portrayed would not be very favorable. For all this, it will give better results if used within its vocation that is more for photos of half body, groups and landscapes.

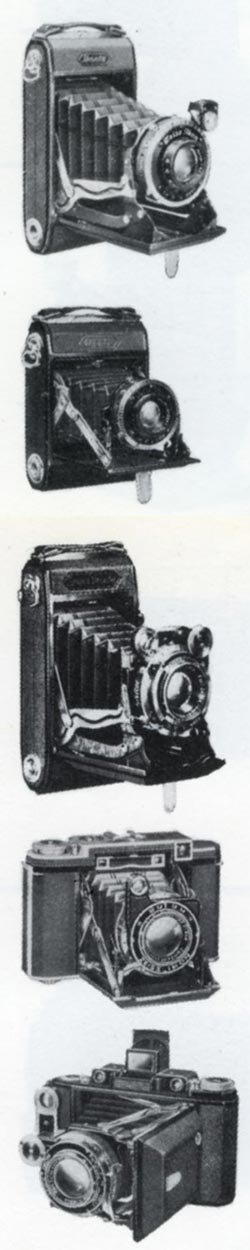

Super Ikontas in Zeiss Ikon line-up

In this 1950s advertising we can look back over the major developments that would follow. TLRs (twin lens reflex) have always been the domain of Franke & Heidecke with Rolleiflex. They launched and knew how to explore the concept. Even though Ikoflex was an excellent camera, it was never strong enough in this market that would soon decline to give way to mid-format mono-reflexes. It was the turn of the Hasselblad and the like. Contaflex did represent the future, as it was a SLR (single lens reflex), a mono-reflex. But despite the many technologies and concepts that Zeiss Ikon had put into this category, theis insistence on using the shutter on the lens, it seems, was one of the factors that set her off competition. It was beaten by far by the Japanese Nikon, Canon, Pentax, Olympus, among others, with focal plane shutters. At Contina, we can see it in the generic category of viewfinder cameras for the amateur market. Zeiss Ikon had dozens of cameras for this segment and they were very successful around this time. But Zeiss again missed the segment to more daring point-and-shoot concepts such as Olympus Trip and Pen. The Contax range finder camera, a true “system” with all sorts of accessories for all types of photography, first-rate optics, has innovated at so many points but never reached the aura of Leicas and, anyway, both declined as a category. .

Finally we see Super Ikonta IV in the picture with its bellows. The whole concept could not survive the futuristic design revolution of the 1960s. It is a camera with many qualities from the point of view of practicality, but it had too many elements of a world that ended with World War II and everyone wanted to forget. Today Super Ikonta is a cult camera and, unlike those who rejected it despite its qualities, we tend to like it, despite its shortcomings.

Super Ikonta A

Super Ikonta B

Super Ikonta C

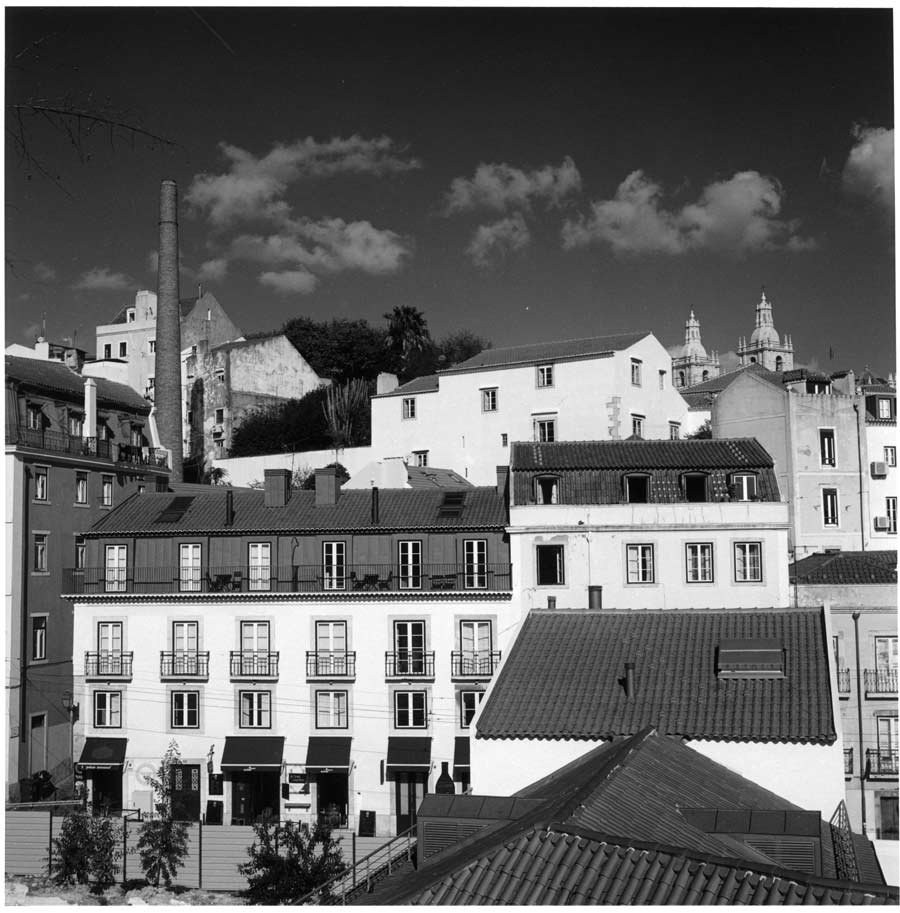

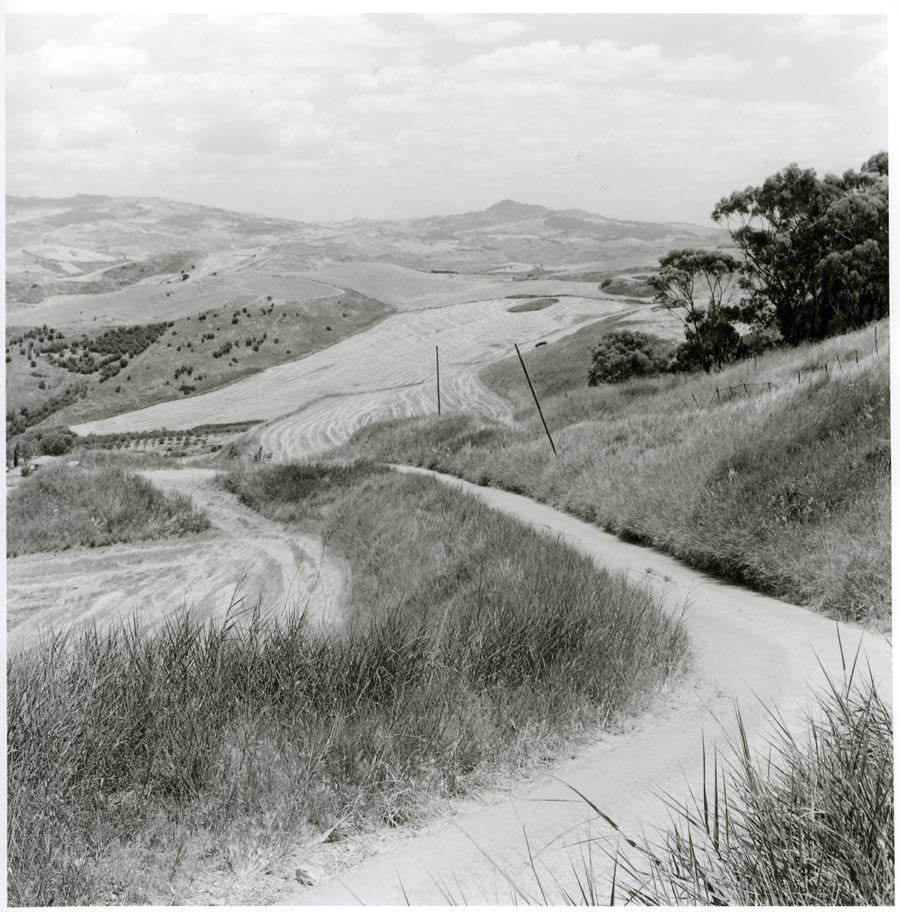

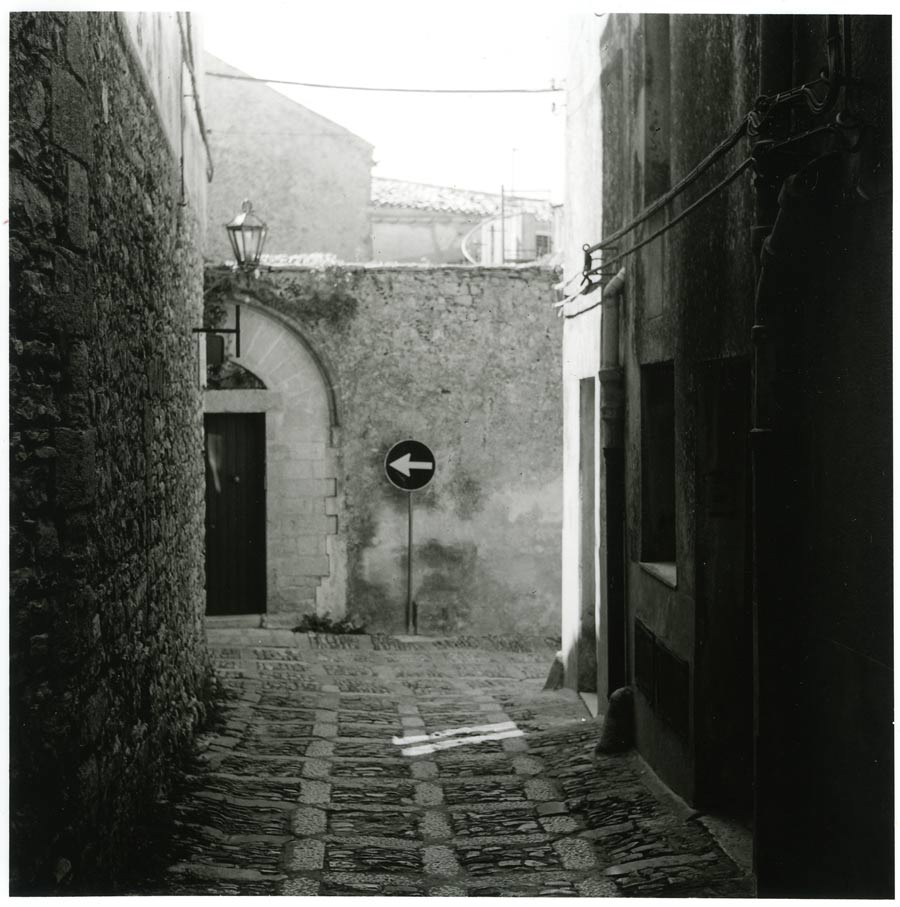

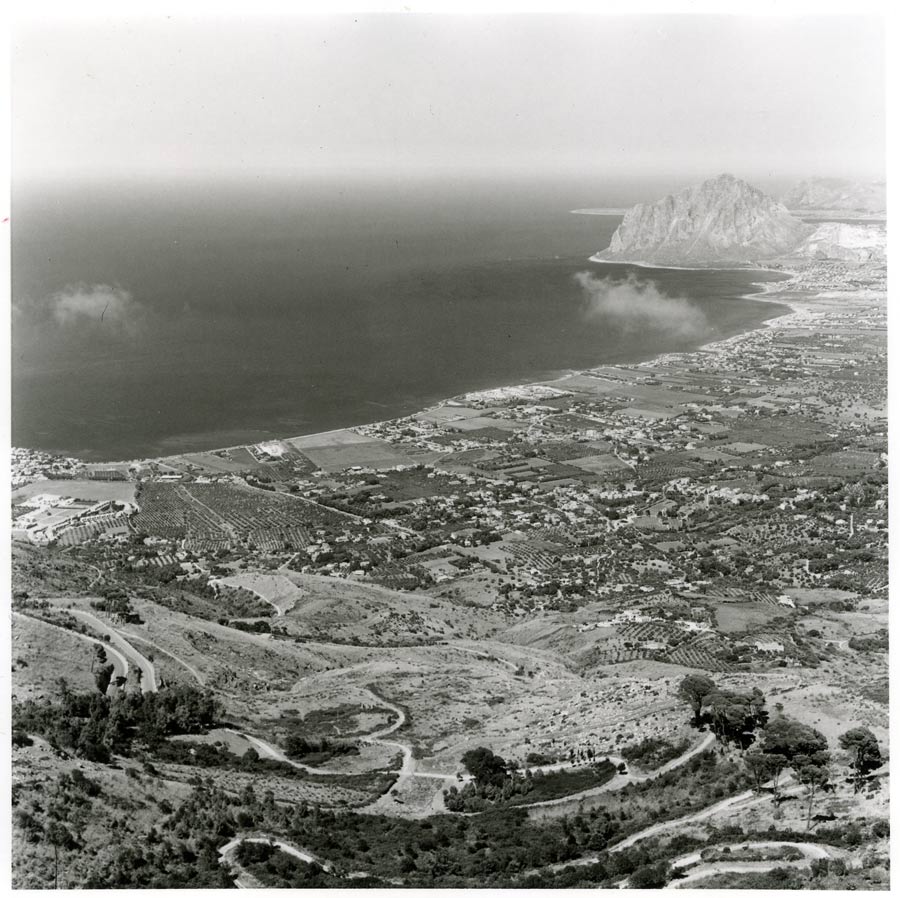

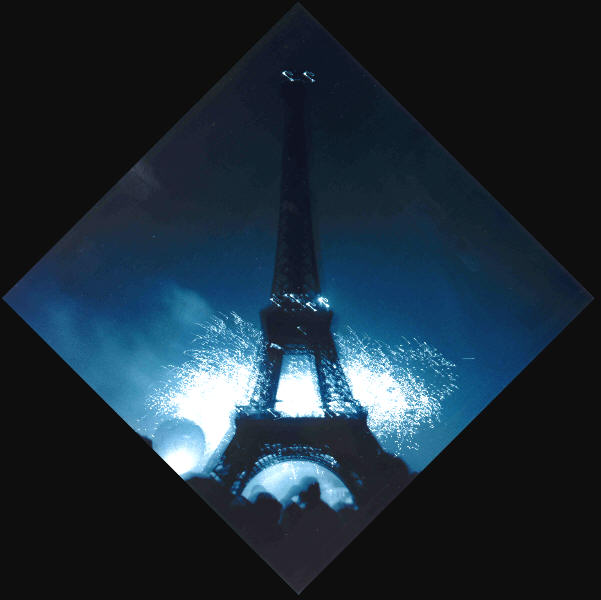

I used these cameras a lot. Super Ikonta IV I received it recently but I have already taken a trip with it and it was a great pleasure. Here is a small gallery with some pictures. The model used is in the comments.

I am very happy with my SI III. If I stop down the simple Novar f3.5 lens to at least f8, it will easily rival the Tessar .

Je viens d’acheter un super ikonta IV

J’ai pris un réel plaisir à lire cette article. J’ai hâte de l’emmener avec moi en ballade.

Cela me rappelle que cette année je n’ai pas pu aller à la Foire Photo à Bièvres 🙁

Profitez bien de votre nouvel appareil. C’est un appareil très agréable à utiliser.

Excellent overview of Super Ikontas! Reading it reminded me of the reasons I love my Super Ikonta IV