– 223 mm | f/3,6 | ~1890 –

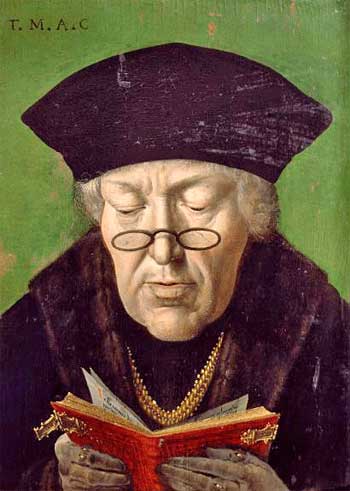

Derogy is among the most important French photographic lens manufacturers. It was founded in 1820 in a region 120 km north of Paris, called Songeons. Since the early eighteenth century, the small towns that made up Songeons already produced spectacle lenses, spectacles, prisms, magnifiers, mirrors and other applications for optical glass. Historically, since the Middle Ages, Italy was the great supplier of optical glasses for the whole world. Especially Venice, where there was already a guild of opticians founded in 1284; this attests to a high degree of importance and organization (History of Eyeglasses).

In the fifteenth century, Florence assumed the leadership that continued in Italy. It was only with the dizzying growth of the press, with the hundreds of periodicals published in the seventeenth century, that the eyewear market also grew enormously in order to supply a mass of new readers. Gradually, it boosted a local industry that flourished in other European countries, among them France.

The growth of Protestantism must also have influenced the appearance of a reading public as the new religion encouraged a direct relationship of the believer with God through the reading of the Bible. Practice that the Catholic Church openly inhibited, claiming to the priesthood the role of exclusive mediators between the faithful and the sacred books. Beyond the functional aspect of spectacles, already in the Renaissance, wearing glasses was seen as something elegant and indicative that the person would be cultivated and inclined to studies.

The optical industry on the eve of photography

At the beginning of the 19th century, in Songeons, the sector occupied a prominent place in region’s economy. The book Description du département de l’Oise, written by Cambry in 1803, reports 80 lunettiers (workers in the production of glasses) and 250 frotteurs de verre, glass polishers, for spectacles and other applications. Only in glasses did they produce the impressive sum of 920 thousand units annually. Cambry still estimates the quantity of other products in optics at 34,000 units.

The production was still in a practically medieval model. In a publication of 1836 (Précis statistique sur le canton de Songeons, arrondissement de Beauvais – Oise ) we read: “The manufacturing of eyeglasses was introduced in 1730. The tradesmen who live in Songeons receive the glass from Paris, distribute them to the polishers and, once the parts have been returned with the proper polishing, those are mounted on frames and delivered for trade. ” This industry lived, just before the invention of photography, the passage of autonomous work, performed at home, certainly involving the whole family and paid for production, to manufacturing in factories, with specialized professionals, with schedules and wages based on purchase of worker’s time.

If the polishing was homemade, the assembly of the optical devices, including the simple spectacles, was already centralized, because tubes and frames required more machines, a finer mechanic and on top of that used noble materials. It was carried out in small factories employing few workers. We read in the Precis statistique quoted above: “M. Cazette recently established in Songeons a small factory that employs a dozen workers and makes spectacles in gold and silver, this nascent company makes very beautiful products.” In his description, Cambry explains the profile of the lunettiers: “Four or five months is sufficient to train an intelligent worker: women and children of ten or twelve years old, to produce glasses with great precision and skill.” The children did not have the status they have today, and they anyway worked hard at home and in farms. When factories were opened, no one saw anything wrong in recruiting them for the new jobs.

On the other hand, the frotteurs de verre had their activity more often as a supplementary income. Especially in winter, when the crop had no demand, they dedicated themselves to polishing: “They work on their own and can produce twelve dozen glasses a week … However, these quantities are very variable, since polishing requires ability, strength and long experience “(also in Précis Statistique).

Lens polishing can be quite simple. The problem with its manual execution is that it is strenuous work because it requires repetitive effort for a long time. What is gained from mechanization is productivity and relative precision. I say relative because it is known that a good optician, knowledgeable of his profession and careful in the execution does not fall behind automatic machines for lens production. Even in large industries, historically, prototypes were always carried out with great deal of manual work and with not detriment in quality. Petzval himself, after quarreling with Peter Voigtländer in 1845, began to produce alone, without even assistants, the lenses he drew (see Petzval’s lens). A motorized machine, such as the polisher above, takes 30-60 minutes to polish a lens. The same work performed manually would certainly consume hours of great effort and attention.

After this long phase in which an already mature industry depended on manual and homemade polishing, it was the use of hydraulic energy, of the mills that were installed in the course of rivers, that allowed the acceleration of the process at the cost of centralization in factories. But the transition was not easy and did not occur without resistance from the frotteurs de verre. It is well known that the Industrial Revolution was a painful process. The whole society threw itself, without seeing another alternative, in a very radical and apparently (until today) path with no return. We read in the Précis Statistique, noting that it is from 1836: “In 1834 Messrs. Courtin and Michel established a mechanical motor with hydraulic power in the municipality of La Chapelle-sous-Gerberoy, to replace polishing by hand which is still practiced. The entrepreneurs, without finding workers to help them, had to give in to the expected resistance that their misunderstood personal interest was faced with. ” But pressure for more production continued and mechanization was forcibly accepted.

Wallet and Derogy

The company founded by Pascal Wallet in 1820, and which would later be taken over by his son-in-law Eloi-Eugène Derogy, was not one of the most brilliant in design innovations or new concepts in photographic lenses. But it was important because it was one of the first to mechanize and make the transition from the period described above, from homemade and manual production, to industrial. He even developed machinery for this purpose. We also read in Précis Statistique: “Mr. Wallet [Jean-Baptiste Wallet, son of Pascal Wallet], of Ernemont [city within Songeons], developed a polishing machine which he calls a mécanoptique and which is driven by a hand wheel (rue à bras); He prepares about three hundred dozen menisci for spectacles. Mr. Derogy, his brother-in-law, uses a similar process to prepare an equal amount of lens for telescopes [not specified but, by comparison, must be production annual]. Your products are shipped directly to Paris”.

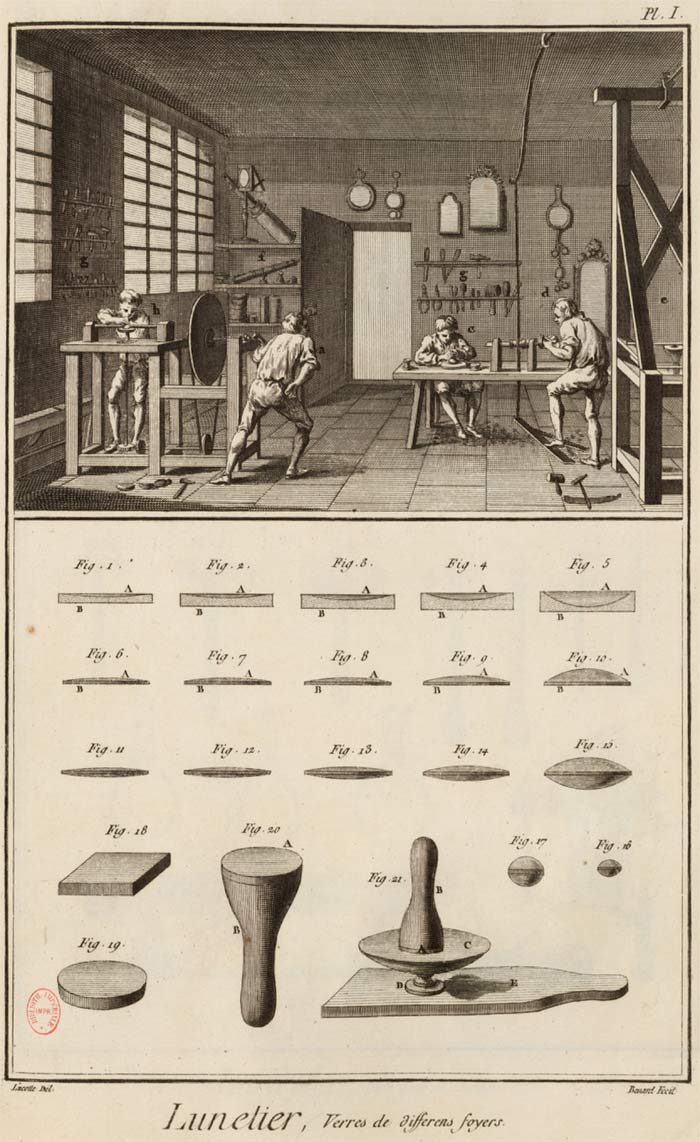

Manufacture of optics according to the Encyclopedia

Diderot and d’Alambert’s encyclopedia, 4th edition 1768, volume V of the illustrative plates, brings some interesting images about the manufacture of lenses at that time. Below I reproduce the boards that illustrate the craft of lunetier.

Above is an 18th century studio. On the left we see two workers on a machine that is also shown in L’Histoire Industrielle De L’Oise. One is the “engine” and the other does the polishing itself. The rotation given to the crank is multiplied by a pair of pulleys and transmitted to the shaft by a crown and pinion system. At the top of this axis rotates the cap that polishes the lens. But the lens still needs to be moved by hand over the rotating mold.

On the right, we see another guy sitting down doing the same job, polishing a lens, but completely manually. The apparatus used for this is detailed below on the page: Fig 18 is a block of raw glass (square), Fig 19 is rounded glass, in disk shape, Fig 20 is glass A mounted on a handle B (molette), Fig 21 we have the mollete with the glass in the position where it is rubbed in a basin that will give the glass a spherical shape to form the lens. The movement of the hand is like moving a spoon while making it, at intervals, also rotate on its axis.

The rightmost worker operates a small lathe, but we don’t have details on what exactly he does. Perhaps prepare a mold, a concave or convex cap. Note that the shaft rotation is produced with a pedal activated by the lathe operator himself.

In the center of the page are flat concave lenses, “to make objects smaller”, flat convex “to make objects bigger”, and bi-convex lenses for magnifying glasses and telescopes. The nearly spherical shapes in Fig 17 and 18 are microscope lenses. These are the products of the atelier.

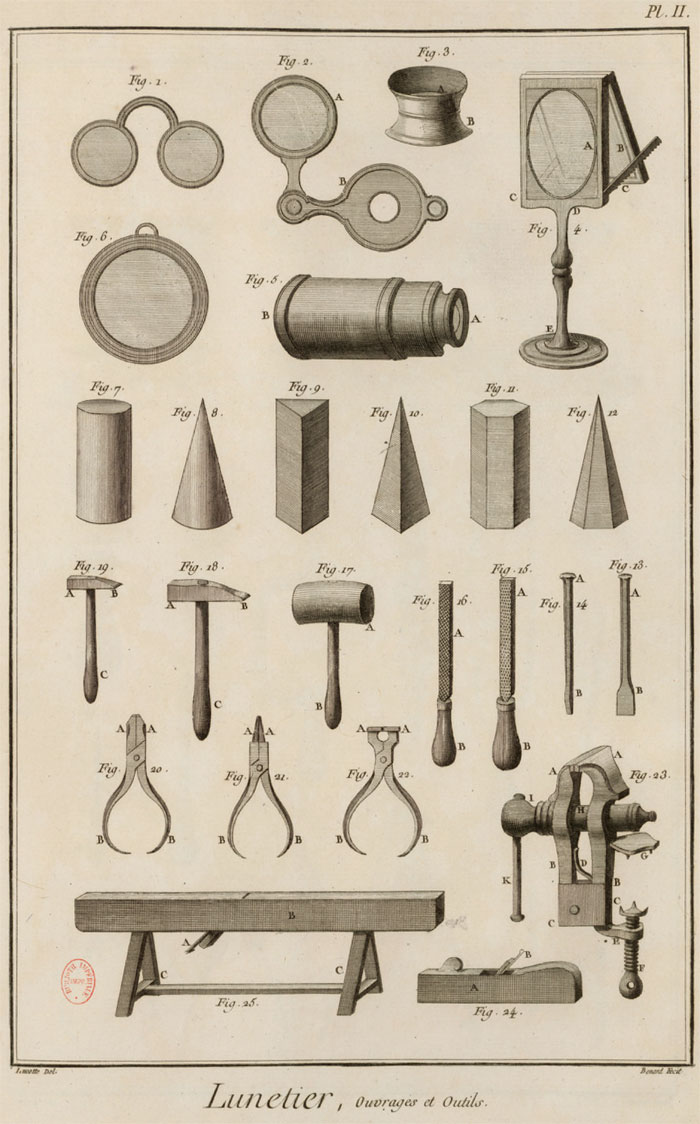

On this board we have at the top a pair of glasses, an articulated monocle, a jeweler’s magnifying glass, Fig 5 is an opera bezel, several prisms and tools.

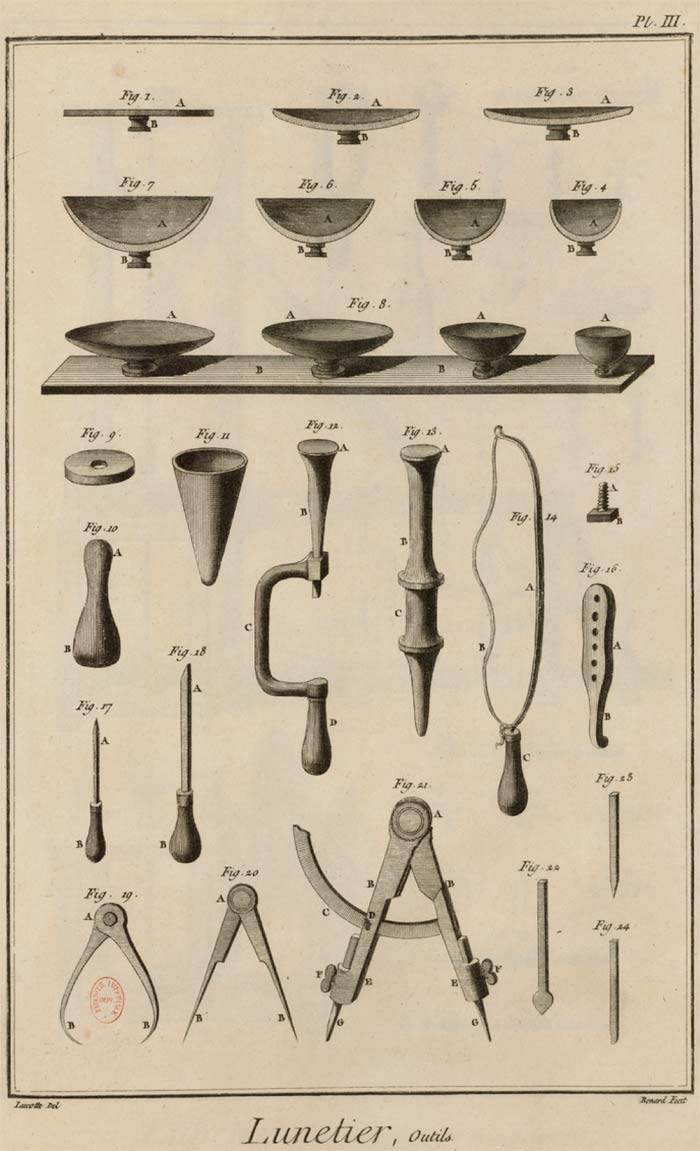

On this plate III we have at the top the various “basins” that are molds to give different curvatures to the lenses and more tools in the second half of the page.

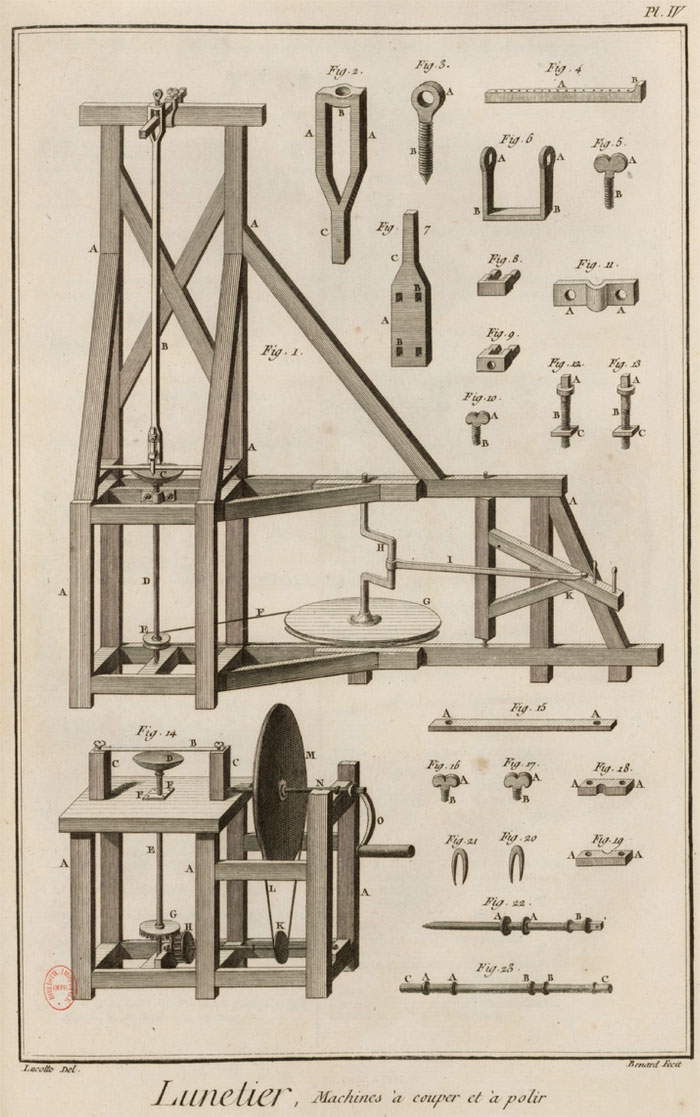

On this IV board, we have two large machines in detail. The first is used for cutting eyeglass assemblies and also for polishing. Below is a detailed view of the lens polishing machine, as it was shown in operation on plate I.

With this type of equipment, not only glasses were manufactured, but also telescopes, prisms, microscopes and a huge amount of optical, scientific and industrial equipment that made it possible to lay the foundations of modern experimental science and the industrial revolution that followed. Photography was another development of this technology that was developed in workshops like this one.

From Maison Wallet to Derogy

With Jean-Baptiste Wallet, son of the founder, the company expanded considerably and remained active until the beginning of the 20th century. They had a laboratory and shop in Paris. But an important part of its production remained in its factory in the town of Cany in Songeons. They produced single lenses (achromatic doublets for landscapes), double Petzval-type lenses for portraits, various types of Rapide Réctilinéaire, wide-angle, lenses that could be disassembled and recombined to offer different focal lengths and also photographic cameras. In 1848 Eloi-Eugène Derogy, Jean-Baptiste Wallet’s brother-in-law, becomes a partner in the company and at some point assumes the leadership and the company simply becomes Derogy.

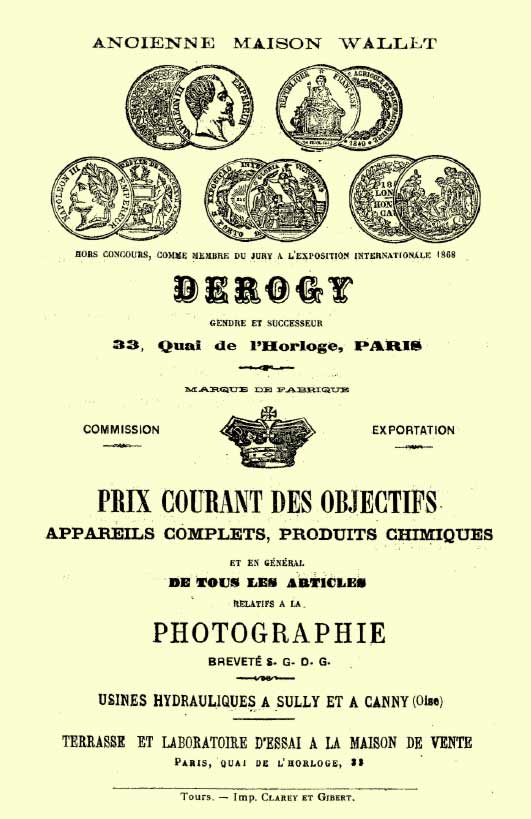

The cover of a price catalog, reproduced above, is full of interesting information:

- It tells that Derogy comes from the old house Wallet (ancienne maison Wallet)

- They participated as hors concours in the international exhibition of 1868 because they were members of the jury. This shows the prestige they enjoyed.

- The name Derogy is, this is somewhat curious, introduced as “son-in-law and successor” (gendre et sucesseur).

- It indicates that it is a brand of a manufacturer, because there were many distributors who manufactured in third parties with own brands or even without any brand.

- It mentions factories in Sully, where Derogy began his career as an optician, and also in Canny, in the valley of the river Oise, where it was the beginning of the maison Wallet.

- In Paris, Quai d’Horloge, 33, there is, on top of the store a, Terrasse, I suppose it is an open photographic studio and a laboratory for testing equipment and lenses.

To close this most historic part follows the full transcript of entry that appears in the Catalogue explicatif et raisonné des produits les plus remarquables admis à l’exposition quinquennale de 1844 (Explanatory catalog of the most notable products admitted to the quinquennial exhibition of 1844). The reason for this long quotation is that it comments on the mécanoptique, also about products line-up, the aggressive pricing policy (maybe thanks to mechanization) and lets us glimpse a little on the euphoria that, in the nineteenth century, must have been the idea of discovering nature and study of the sciences as “imperative need for all classes of society “. Finally, as early as 1844, he cites the production of photographic lenses for the newly discovered Daguerreotype, presented to the public in 1839.

|

Wallet brothers, opticians. Knowledge of the natural sciences having become an imperative need for all classes of society, it was felt that the study was the only way to satisfy this need. It is imbued with this truth that Mr. Wallet brothers have devoted themselves to the construction of physics instruments of all kinds. But, it is especially to the optics that they devoted their care and their efforts. They have, for example, been busy perfecting an achromatic microscope for simple, convenient, and very cheap use. This instrument will, we have no doubt, astonishes the public, who will be in a position to see with their own eyes all of its perfections. MM. Wallet have been, moreover, and for a long time, much occupied in perfecting spectacles of all kinds, and other optical glasses, such as lenses, mirrors diverging and convergent, etc. They can announce today that their attempts have been crowned with complete success. These builders now obtain the glasses we have just mentioned, with the aid of a precision instrument which they call mécanoptique, and which they invented. They argue about this instrument, to demonstrate their superiority of this kind, Furthermore, desirous, above all, of being useful to society in general, they have reduced their prices so that they sell their glasses, of a recognized superiority, at the same price as ones in bad quality delivered daily to the trade. On the other hand, to put the public in a position to judge by itself the quality of glasses, MM. Wallet brothers have exhibited a device whose purpose is to make apparent to the less experienced people those qualities good or bad. They also exhibited an achromatic magnifying glass made up of large plumps, free from spherical aberration, for the use of engravers and watchmakers. There will always be in their stores an assortment of glasses of any shade and any curvature. They have meniscus, they have crystals, and so on. They also hold lenses for microscope, achromatic lenses for opera glasses, telescopes, daguerreotypes, etc. |

This lens

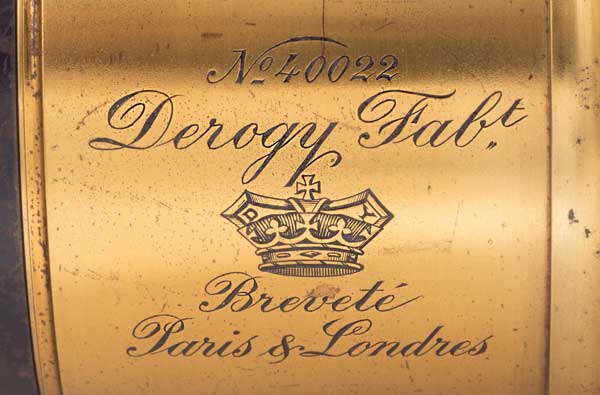

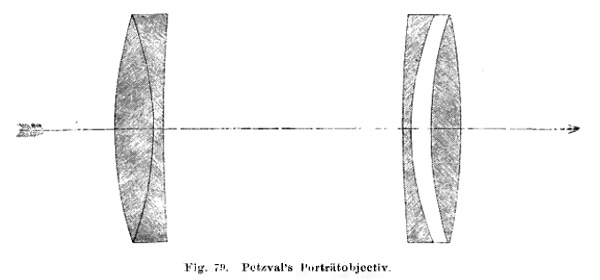

The rather high serial number, 40022, indicates a production already towards the end of the nineteenth century or even beginning of the twentieth. I did not find any secure reference to precise this date. Major manufacturers have kept Petzval portrait type lenses in production for a considerable time. If we think that it was created in 1840, this specimen has already left the factory with a formula of approximately 60 years. Even the Waterhouse diaphragm was used when the iris was already a common item during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Some opticians, such as Dallmeyer, modified and adapted the original Petzval. But this lens follows the original scheme, at least in respect of curvatures’ sequence, shown in the scheme below.

It brings a Rapide No. 4 engraving on the opposite side of the name Derogy. The diameter of the front lens is 68 mm. The length of the lens including lens hood is 135mm.

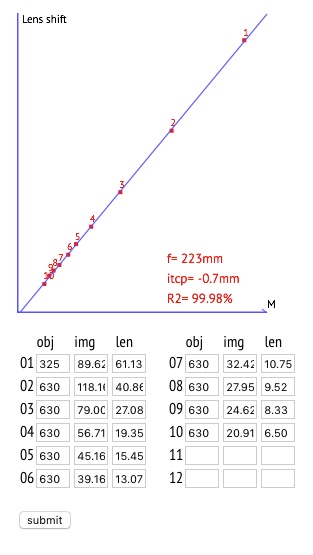

Its focal length was calculated experimentally (chart below) and the result was 223 mm with an excellent correlation of the data. The entrance pupil is ~ 12% larger than the diaphragm. After measuring and calculating I found a maximum aperture of f/3.6. Exactly the value of Petzval’s original drawing.

The illumination circle, regardless of the image quality, is 210 mm. Enough to cover, without vignetting, but with no freedom of movement, a 13 x 18 cm sheet. But in a portrait it is very important to be able to move a Petzval lens to match the area of good sharpness with subject’s face, or better still, with the eyes of the portrayed, which is not always in the center. So I would say that this lens works well for ¼ of plate.

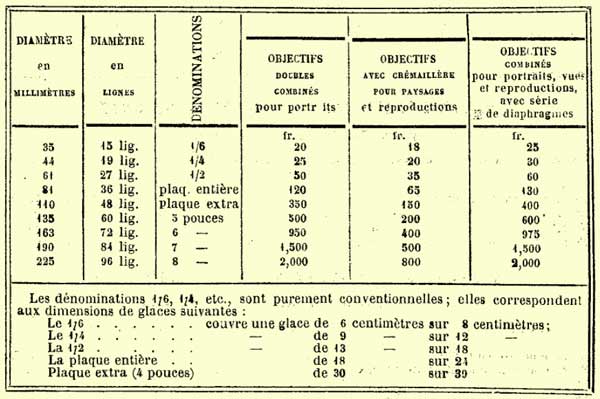

In the above table, from the catalog earlier mentioned, printed after 1868, we see that the lens for ¼ of plate (9 x 12 cm, almost 4 x 5 inches) is 44 mm in diameter, while this specimen has 68 mm. As the catalog does not mention the aperture, perhaps this is the explanation for Rapide nº4. The lens in the catalog certainly did not reach f/3.6 like this, and this justifies the addition of the term Rapide.

With this focal length and this circle of illumination we obtain a 50° angle of view when focused at infinity. The sharp image circle, farther from which it is already possible to perceive, on the ground glass, some quality loss, is of 60 mm. Of course, this is a subjective assessment. The corresponding viewing angle is 15°. This is completely in line with what Josef Maria Eder says in the Ausführliches Handbuch der Photographie of 1893 on Petzval lenses: “The field of vision varies between 15 and 55 degrees, but rarely has more than 20 degrees of total sharpness use larger openings. “

There is a bit of oxidation at the edges of the front element, certainly the balm, but the overall condition is very good and perfectly usable. The manufacturing quality of Derogy lenses is certainly a strong point of this manufacturer.

The lacquer applied on brass lenses during the nineteenth century was shellac. It is an alcohol based varnish that was used a lot for furniture and wooden musical instruments. It is extremely hard after dry and cured and preserves the metal very well. This lens was re-varnished by myself. Opinions are divided among collectors whether or not this is a procedure to adopt. I think even Rembrands have their varnish changed from time to time because what matters is the painting underneath. By the same logic, I changed the varnish of some of my lenses when their appearance was very miserable. A lens is a tool to which a varying degree of fetish can be attributed. I like them very much but I do not fell like treating them as objects of worship. The main point to evaluate, in my opinion, is whether the procedure poses any greater risk to the functionality of the lens. If this is not the case, I see no impediment whatsoever.

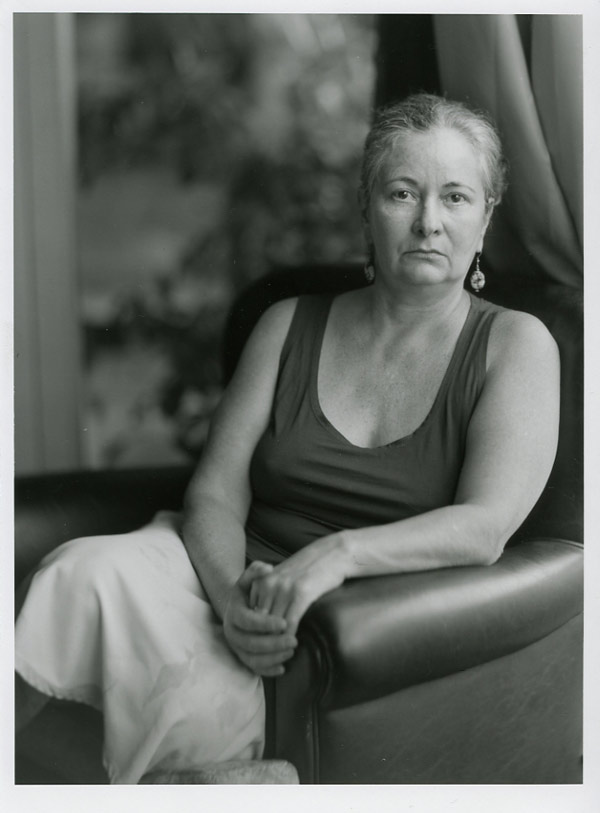

This is a portrait made with this lens. I used Ilford FP4 film in 9×12 cm format. It was developed in Pyrocat HD, in tray, for 16 minutes at 20ºC. The above image is a scan from a print, made in Ilford Fiber Glossy, 18 x 24 cm in size. A Waterhouse stop was used down to f/4. I just wanted to avoid the oxidised balsam at lens border. I used 2 cm lens shift to the left and tilted lens board and film-holder backwards in order to get the lens axis pointing exactly on Thais’ face. I tried another shot, only focusing the lens on her eyes, without lens movements, and it is noticeable how aberration downgrades the image although it is in focus. Below I show two scans directly from negatives. They illustrate this effect as all the rest remained exactly the same:

The only way to improve the second image would be by stopping down the lens. My conclusion is that it is very important to aim lens’ axis to what you want to be at the best image quality. Follow this link to see a basic discussion about this procedure to decentralize the lens axis.

About the lens itself, I think it is a wonderful piece of optics. With a few exceptions I don’t like very much the exaggerated effect obtained when Petzval lenses are used beyond the image circle they were originally designed for. For me it is enough and very welcomed the softness it brought to arms and body while keeping a crispy rendering on the face. It is delicate, well balanced and added to the at home and informal atmosphere of this picture.