Retina Reflex III | Kodak

Kodak was one of the giants of photography and for decades it was the largest manufacturer of photographic films. This should be, for most of those who have had some contact with the brand, the first memory it brings: Kodak films. But it is also important to say that many Kodak cameras have made history, starting with box camera Brownie nº2, which launched the film 120, used until today. They also made large, folding, bellows cameras that were hugely successful. Then came dozens of very simple models, in bakelite and plastic, for 127 films, such as the Kodak Baby Brownie Special. Finally, more at the height of analog photography, in the 1960s and 1980s, a series of low-cost cameras for films 126 were produced by the millions around the world.

What is perhaps less known is Kodak’s share of the more sophisticated 35mm film camera market. This attempt into an area to a certain extent outside its vocation, a company that has always called itself the role of popularizing photography, produced a line of cameras that are today a joy for those who like analog photography and collect old cameras. These are the Kodak Retina. An extensive series of models that started as viewfinder cameras in the 1930s, then rangefinder in the 1940s, and in the end, in the 1950s, Retina Reflex, a single lens reflex (SLR), was added to the series. All of them built solidly and with very good and sometimes even surprising optics.

The first Retina, due to its position as an extension of a film company, was launched together with 35 mm film in preloaded disposable 35mm film cartridges. Until then the film was purchased in bulk rolls and loaded in reusable cartridges. That was the case with the then recently launched Leica which was first commercially introduced in 1925. It was among the first to use the 35 mm perforated films that were originally produced for cinema. For this reason, the film needed to be manually spooled in a cartridge suitable for cameras.

Above we see a robust reusable cartridge from Zeiss Ikon, with its elegant metallic box. Next to it, a disposable (recent) cartridge, in the format launched by Kodak in 1934, which would become an industry standard.

It is curious to think that the directors of Leitz, while studying to launch the new camera, were really concerned if the cinema films would improve enough for use in photography in order to render the quality that the optics designed for Leica could offer. In cinema, high sensitivity is more important than fine grain, in photography, which allows longer exposure times, the ratio shifts more in favor of fine grain. These cartridges for specific use in the new cameras were decisive in giving full autonomy to the new package and use of 35 mm film in photography. New emulsions were developed bearing in mind the specific needs of the still image and its further processing. It was another revolution in the act of photographing in which Kodak played a fundamental role.

It is still curious to think that nowadays, in this new phase of analog photography, perhaps agony, perhaps rebirth, many people are returning to buy bulk film to produce their own cartridges. Recovering old “disposables” in the trash or buying reusable, vintage or new ones, which still appear on the market. It is a way to lower the unit cost and have greater flexibility in the number of photos per film.

It is probably also not well known that this line of Retinas was neither created nor manufactured in the United States. We know that Kodak is an icon of American entrepreneurship. Its founder, George Eastman, is celebrated as a national hero. He was a role-model, typical entrepreneur, coming from humble beginnings, was creative, took risks, worked hard and built an empire. This undeniable business acumen was enough to make him realize that Rochester would not be the ideal place to attack the market for cameras with more ambitious specifications. Germany, yes, was a center of excellence in cameras and lenses, with many firms, start-ups we would say today, small and promising waiting for capital. In 1931 Kodak bought Nagel Camera Werks AG, in Stuttgart. The firm was only 3 years old, but belonged to August Nagel, an experienced and creative designer, one of the founders of Zeiss Ikon. That was how Kodak AG was born, the cradle of Retinas. The AG, when accompanying the names of German companies, refers to the type of company, is a Ltd company. AG stands for Aktiengesellschaft.

This short introduction was only to position Kodak Retina Reflex as the culmination of a long line of development of German cameras that, although they did not penetrate the professional market, were not of inferior quality to that of their best competitors. They were very good and reliable in what they set out to do and in the concepts they supported. The Retinas that were minimally well maintained are still fully functioning and will continue to do so for a long time.

Kodak Retina Reflex

The Retina Reflex were manufactured from 1957 until 1966 with important differences between the models in this relatively short time. The former had a suffix C that identifies a lens system in which only the front elements are replaced to offer different focal lengths. A group of lenses is permanently on the camera body with the shutter. This is the same system as some Retina Rangefinder with interchangeable lenses that carry the same C.

The above illustration, from Retina IIc, shows what this looks like. The front lens block can be removed and replaced with another one offering another focal length. The rear block remains in the camera. It is the same system as Zeiss Ikon’s Contaflex, launched in 1953.

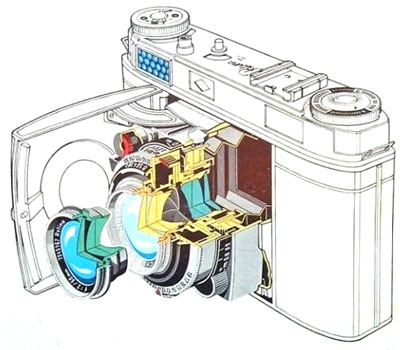

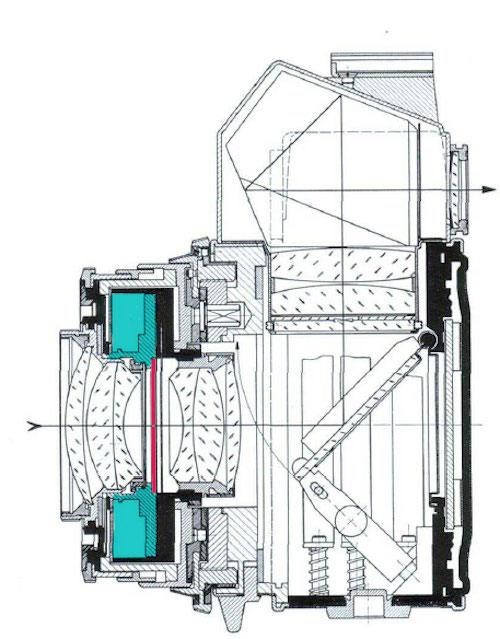

In this new illustration we have the same type of C lens on a Retina Reflex. The shutter, a Synchro Compur, is in a box in the form of a thick ring with a more or less square section marked in blue in the vertical cut of the drawing above. The shutter blades are positioned approximately on the red painted stripe. The lenses on the left are removable and those on the right are part of camera body.

The C system in a SLR camera was not very well received as Kodak AG quickly offered a new Retina Reflex without fixed lenses on the camera body. We can imagine how difficult it must have been to take the Synchro Compur shutter behind the entire optical setting and providing yet room for the movable mirror between shutter and the film. This was done from 1959 when Retina Reflex S was launched, in this new version the lenses are complete and independent optics.

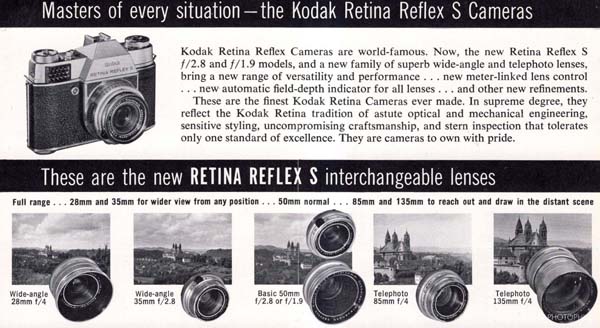

The new arrangement allowed for greater flexibility and better final image quality, as each lens design is optimized for a specific focal length. In the leaflet reproduced above we see lenses from 28 mm to 135 mm, but there was also the option of a 200 mm f / 4.8. Retina S also offered a light meter coupled with speed and aperture adjustments, so that by varying these parameters it was possible to reach the correct exposure. It was an advantage over cameras with a light meter that had to go through the numbers EV (exposure value) or any other measure of luminosity, and then presenting the matching pairs speed/aperture.

I find the last sentence in the text of the leaflet above curious: “They are cameras to own with pride.” It seems like a reminder pronounced with a certain bitterness. By that time, the cult image, the intangible value of cameras like Leica, Contax or Rolleiflex were consolidated. It must have been difficult for Kodak AG’s engineers to understand why their Retinas, so well designed and manufactured, were not part of this pantheon. Was it due to the tradition of popular Kodak cameras? Perhaps. But there was something else that was not right and that only time could show.

Kodak Retina Reflex III

The Retina Reflex III was produced from 1960 to 1964. A change from the S is that in addition to having the light meter attached, the coupling is visible on the camera’s viewfinder. When acting at speed or aperture, the clamp-shaped pointer must coincide with the simple pointer that fluctuates according to the condition of the light. The ISO adjustment can be done on a ring on the camera top plate.

There was also a Retina IV in which it was also possible to see speed and aperture on the camera viewfinder through a window on the front panel that covers the prism. A development that was also featured in Bessamatic Deluxe, from Voigtlander, at about the same time. I don’t know which one was the pioneer. Those were mechanical and optical solutions that would soon be solved with leds and displays on electronic cameras, probably for a fraction of the price.

The indication of the light meter is also visible in a small window at the top of the camera. But, check at the above picture: where’s the film advance lever?

It’s on the bottom. This is an idiosyncrasy of several Retinas. As the axis of the film reel goes from top to bottom, I think it’s smart that they have asked themselves, why not below? In use, this is an easy feature to get used to. But I don’t think that is exactly an advantage.

At the base of the camera is also the frame counter. It uses the countdown system and when it reaches 1, it locks the camera. It is no longer possible to advance the film because it is understood that there is no more film to advance. It is a bit authoritative because films are not so accurate, you can always try a last photo beyond 36. But to release it you have to slide the button with the arrow (to the left of the counter) and so the camera understands that you loaded a new reel. If the film has less than 36 poses, it is necessary to slide the button several times until reaching the corresponding number of photos. This, of course, is just in case you want the counter to count correctly.

The small toothed wheel that appears at the base that holds the lens, just above the counter, is where the apertures are adjusted. The idea is probably that the photographer will adjust the speed first, according to the type of subject he wants to photograph, and only then the exposure fine adjustment is made by looking through the viewfinder and using this ring at the base of the camera.

It is not a bad idea as a workflow, but considering that the iris is a device in the form of a disk, coaxial with the lens tube, an external ring would be the most obvious, simple, inexpensive solution and should not be a surprise that it was later consecrated.

Inside, where the film is transported, the Retinas are well constructed and the guides designed in order to facilitate the loading of the film and its transport without suffering any type of scratches or abrasion.

Lenses

The normal lens on the Retina Reflex is a Retina Xenar 50 mm f / 2.8, manufactured by Schneider. This is a 4-element lens in three groups with the Tessar concept. The Retina Reflex III, from my collection, has a 50 mm f / 1.9 Xenon as its normal lens. This is a sophisticated lens with 6 elements in 4 groups and designed by Tronnier in 1935. Albrecht Tronnier was an important optician who created and redesigned many famous lenses. For Voigtlander, for example, he worked at Color-Heliar, Ultron and Nokton. Xenon has undergone adaptations and revisions and there are versions with 7 elements and different apertures.

With the same 50 mm and f/1.9 there are the Retina-Xenon and only Xenon versions. The latter was sold with Instamatic Reflex (camera for 126 films) and Retina-Xenon was specific for Retina Reflex for 35 mm films. I think the main, maybe only difference, is that Retina-Xenon has sliding pointers that indicate the depth of field. Something very comfortable and better than the traditional engraved scales, as is the case of Xenon in the photo above. In addition, I have already photographed with Xenon on the Retina Reflex III and there was no problem.

In this photo we see two lenses that complement the normal lens, forming the traditional kit: normal, tele and wide angle. In the camera is the Retina-Curtagon 35 mm f/2.8 and the other one is a Tele-Xenar 135 mm f/4.0. Unlike Bessamatic, each lens from this basic set: 35, 50 and 135 mm, requires a different filter thread. Curtagon even uses a bayonet system.

The shutter release button

The point where the Retina Reflex III really falls short is in the positioning of the release button. In the first viewfinder Retinas, still in the 30s, it was conveniently positioned on top of the camera. That was the case even with the Retina Reflex S. In this position it allows us to firmly grasp the camera body and leave the indicator free to fall naturally on the shutter button. But in Retina Reflex III, certainly due to design difficulties, perhaps due to cost restrictions, it was positioned at the front, next to the lens.

When the button is at the top, we can press the camera between the middle of our index and the base of our thumb on the opposite side. By pressing the prism or visor against the forehead, we have a very stable situation. We just move the tip of the indicator to trigger the shutter while focusing with the left hand thumb and index finger. While with the trigger in front of the camera, it is more difficult to obtain the same level of stability

I believe that Kodak itself did not like this solution very much. The photo above is from a Retina Reflex III manual. Kind of defensive, isn’t it? It is like a “Sorry by that” was missing.

Yet about the shutter release, it is important to note that like the Contaflex from Zeiss Ikon and the Bessamatic from Voigtlander, all these cameras, did not offer an instant returning mirror after firing the shutter. That means, you get a black viewfinder each time you take a picture. That is somehow useful as a moment to think about what you just did. After this brief reflection, while the image you just had and capture still floats in your mind, you can advance the film. By doing so, you cock the shutter, bring the mirror back in position and you are then all set to go after the next one.

Who would have guessed?

Criticizing these German cameras from the 50s is a bit of an exercise in predicting the past. After the Japanese companies arrived with the new construction pattern, of how and where to position the controls and new materials, they swept all these experiences from Kodak AG, Voigtlander and Zeiss Ikon out of the market. Now reviewing, it is easy to point out the tests made by these companies as “mistakes”. Ihagee’s Exakta, located in Dresden, is an exception in several respects, starting with the curtain shutter that it adopted from the very beginning. However, its design was dated and would need a complete overhaul. But for other reasons, mainly the war and the administration that took over the company, it did not flourish with the strength that its initial arrangements would allow.

I believe that the fairest thing is to consider that the concept of SLRs, which until then was a niche, was yet to be massively adopted and still in the development phase. Many creative solutions, from the engineering point of view, were implemented by the industry giants that were still testing the waters. It draws attention, for example, the speed with which new solutions, with significant changes, were adopted. Probably those jumps to new designs were made before the previous one, with its tooling and marketing efforts, had been paid by a substantial volume of sales. But these giants were perhaps too steeped in the past, on premises that they did not think could be challenged, and so they lost their moment and direction.

Below some pictures I took with this Retina Reflex. In the ones that I still remember, I put with which lens it was. But I think you can see that they were not made with the intention of showing the qualities of optics. They are not part of any camera or lenses’ “tests”. Only photos taken just for the pleasure of photographing.